Chapter 54

Pericarditis, Pericardial Constriction, and Pericardial Tamponade

1. The pericardium is not necessary for life. What does it do? Why is it important?

2. What diseases affect the pericardium?

The pericardium is affected by virtually every category of disease (Box 54-1), including idiopathic, infectious, neoplastic, immune and inflammatory, metabolic, iatrogenic, traumatic, and congenital disease.

3. What is pericarditis? What are the clinical manifestations? What are the causes?

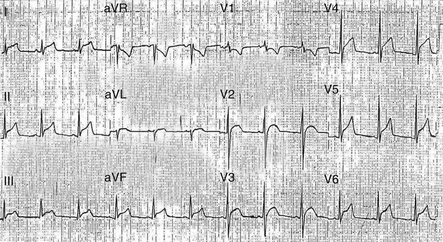

Acute pericarditis is a syndrome of pericardial inflammation characterized by typical chest pain (sharp, retrosternal pain that radiates to the trapezius ridge, often aggravated by lying down and relieved by sitting up), a pathognomonic pericardial friction rub (characterized as superficial, scratchy, crunchy, and evanescent), and specific electrocardiographic changes (diffuse ST-T wave changes (Fig. 54-1) with characteristic evolutionary changes and PR segment depression). Causes include infection (viral, bacterial, fungal, mycobacterial, or human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] associated), neoplasia (usually metastatic from lung or breast; melanoma, lymphoma, or acute leukemia), myocardial infarction, injury (postpericardiotomy and traumatic), radiation, myxedema, and connective tissue disease.

4. Should patients presenting with acute pericarditis be hospitalized? Why?

5. What is the treatment for acute pericarditis?

Acute pericarditis usually responds to oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin (650 mg every 3 to 4 hours) or ibuprofen (300-800 mg every 6 hours). Colchicine (1 mg/day) may be used to supplement the NSAIDs as it may reduce symptoms and decrease the rate of recurrences. Chest pain is usually alleviated in 1 to 2 days, and the friction rub and ST segment elevation resolve shortly thereafter. Most mild cases of idiopathic and viral pericarditis are adequately treated within a week or two of treatment start, but the duration of therapy is variable and patients should be treated until inflammation or an effusion, if present, has resolved. If colchicine is used, it should be given for 3 months; this is based on the randomized, open label Colchicine for Acute Pericarditis (COPE) trial. The intensity of therapy is dictated by the distress of the patient, and narcotics may be required for severe pain. Corticosteroids should be avoided unless there is a specific indication (such as connective tissue disease or uremic pericarditis) because they enhance viral multiplication and may result in recurrences when the dosage is tapered. Although the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recently published guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases, there are only a few randomized, placebo-controlled trials from which appropriate therapy may be selected.

6. What is recurrent pericarditis? How is it treated?

7. What is post–cardiac injury syndrome?

Prior injury of the pericardium, myocardium, or both

Prior injury of the pericardium, myocardium, or both

A latent period between the injury and the development of pericarditis or pericardial effusion

A latent period between the injury and the development of pericarditis or pericardial effusion

Responsiveness to NSAIDs and corticosteroids

Responsiveness to NSAIDs and corticosteroids

Fever, leukocytosis, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (and other markers of inflammation)

Fever, leukocytosis, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (and other markers of inflammation)

Pericardial and sometimes pleural effusion, with or without a pulmonary infiltrate

Pericardial and sometimes pleural effusion, with or without a pulmonary infiltrate

Alterations in the populations of lymphocytes in peripheral blood

Alterations in the populations of lymphocytes in peripheral blood

8. What are the pericardial compressive syndromes? What are their variants?

9. What are similarities between tamponade and constrictive pericarditis?

10. What are the differences between tamponade and constrictive pericarditis?

In tamponade, the pericardial space is open and transmits the respiratory variation in thoracic pressure to the heart, whereas in constrictive pericarditis, the cavity is obliterated and the pericardium does not transmit these pressure changes. The dissociation of intrathoracic and intracardiac pressures (along with ventricular interaction) is the basis for the physical, hemodynamic, and echocardiographic findings of constriction.

In tamponade, early ventricular filling is impaired, whereas it is enhanced in constriction.

11. What are the physical findings of tamponade?

12. What are the physical findings of constrictive pericarditis?

13. What is the role of echocardiography in tamponade?

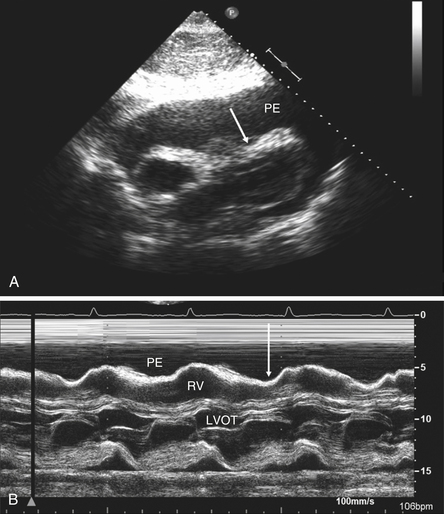

Although tamponade is a clinical diagnosis, echocardiography plays major roles in the identification of pericardial effusion and in the assessment of its hemodynamic significance (Fig. 54-2). The use of echocardiography for the evaluation of all patients with suspected pericardial disease was given a class I recommendation by a 2003 task force of the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE). Except in hyperacute cases, a moderate to large effusion is usually present and swinging of the heart within the effusion may be seen. Reciprocal changes in left and right ventricular volumes occur with respiration. Echocardiographic findings suggesting hemodynamic compromise (atrial and ventricular diastolic collapses) are the result of transiently reversed right atrial and right ventricular diastolic transmural pressures and typically occur before hemodynamic embarrassment. The respiratory variation of mitral and tricuspid flow velocities is greatly increased and out of phase, reflecting the increased ventricular interaction. Less than a 50% inspiratory reduction in the diameter of a dilated inferior vena cava reflects a marked elevation in central venous pressure, and abnormal right-sided venous flows (systolic predominance and expiratory diastolic reversal) are diagnostic. In patients who do not have tamponade on first assessment, repeat echocardiography during clinical follow-up was given a class IIa recommendation by the 2003 ACC/AHA/ASE task force.

Figure 54-2 Echocardiography in cardiac tamponade. A, Subcostal two-dimensional echo. A large effusion (PE) with marked compression of the right ventricle (arrow) is seen. B, M-mode of the parasternal long axis. Note the right ventricular (long arrow) collapse. LVOT, Left ventricular outflow tract; PE, pericardial effusion; RV, right ventricular.

14. What is the role of echocardiography in constrictive pericarditis?

Echocardiography is an essential adjunctive procedure in patients with suspected pericardial constriction. The use of echocardiography for the evaluation of all patients with suspected pericardial disease is a class I recommendation of the ACC/AHA/ASE task force. Echocardiography findings to be sought include increased pericardial thickness (best with transesophageal echocardiography), abrupt inspiratory posterior motion of the ventricular septum in early diastole, plethora of the inferior vena cava and hepatic veins, enlarged atria, and an abnormal contour between the posterior left ventricular the left atrial posterior walls. Although no sign or combination of signs on M-mode is diagnostic of constrictive pericarditis, a normal study virtually rules out the diagnosis. Doppler is particularly useful, showing a high E velocity of right and left ventricular inflow and rapid deceleration, a normal or increased tissue Doppler E′, and a 25% to 40% fall in transmitral flow and marked increase of tricuspid velocity in the first beat after inspiration. Increased respiratory variation of mitral inflow may be missing in patients with markedly elevated left atrial pressure, but may be brought out by preload reduction (e.g., head-up tilt). Hepatic vein flow reversals increase with expiration, reflecting the ventricular interaction and the dissociation of intracardiac and intrathoracic pressures, and pulmonary venous flow shows marked respiratory variation.

15. Are other imaging modalities useful in pericardial disease?

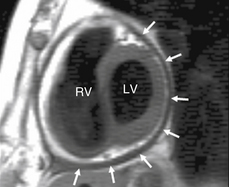

Other imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) are not necessary if two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography are available. However, pericardial effusion may be detected, quantified, and characterized by CT and CMR. CT scanning of the heart is extremely useful in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis; findings include increased pericardial thickness (greater than 4 mm) and calcification. CMR provides direct visualization of the normal pericardium, which is composed of fibrous tissue and has a low magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) signal intensity. CMR is claimed by some to be the diagnostic procedure of choice for the detection of constrictive pericarditis (Fig. 54-3). Late gadolinium enhancement of the pericardium may predict reversibility of transitory constrictive pericarditis (see later) following treatment with antiinflammatory agents.

Figure 54-3 Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating thickened pericardium encasing the heart (arrows). (Reproduced with permission from Pennell D: Cardiovascular magnetic resonance. In Libby P, Bonow R, Mann D, Zipes DP, editors: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders, p. 405.) LV, Left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

16. Constrictive pericarditis is a surgical disease, except when very early or in severe, advanced disease. What is the role for medical therapy in constrictive pericarditis?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Cheitlin, M.D., Armstrong, W.F., Aurigemma, G.P., et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography. Available at http://www.acc.org/qualityandscience/clinical/statements.htm. Accessed February 26, 2013

2. Hoit, B.D. Diseases of the pericardium. In Fuster V., Walsh R.A., eds.: Hurst’s the heart, ed 13, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011. pp. 1917–39

3. Hoit, B.D. Treatment of pericardial disease. In Antman E., Sabatine M.S., eds.: Cardiovascular therapeutics. A companion to Braunwald’s heart disease, ed 4, Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2011. pp. 667–675

4. Hoit, B.D. Management of effusive and constrictive pericardial heart disease. Circulation. 2002;105:2939–2942.

5. Little, W.C., Freeman, G.L. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006;113:1622–1632.

6. Maisch, B., Seferovic, P.M., Ristic, A.D., et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:587–610.

7. Shabetai, R. The pericardium. Norwell, Mass: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003.