W9 Pericardiocentesis

Before Procedure

Before Procedure

Indications

Elective pericardiocentesis is warranted in patients with suspicion of purulent pericarditis. This is a rare disease, but rapid diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent serious morbidity, especially in children and immunocompromised patients. Among patients treated only with antibiotics without pericardial drainage, purulent pericarditis carries a mortality rate of 70%. Treatment consists of systemic antibiotic therapy and complete evacuation of the effusion. Surgical drainage usually is required because percutaneous drainage alone cannot completely evacuate the effusion, which is often rich in fibrin and can be loculated and associated with dense adhesions. An alternative and less invasive method that can be used to completely evacuate purulent effusions, thus controlling sepsis and avoiding the evolution to constrictive pericarditis, consists of pericardial drainage associated with intrapericardial infusion of streptokinase. Fibrinolytic therapy can enhance removal of material that would otherwise be too viscous or particulate to be removed by tube drainage. This treatment should be considered before undertaking surgery.

Elective pericardiocentesis is warranted in patients with suspicion of purulent pericarditis. This is a rare disease, but rapid diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent serious morbidity, especially in children and immunocompromised patients. Among patients treated only with antibiotics without pericardial drainage, purulent pericarditis carries a mortality rate of 70%. Treatment consists of systemic antibiotic therapy and complete evacuation of the effusion. Surgical drainage usually is required because percutaneous drainage alone cannot completely evacuate the effusion, which is often rich in fibrin and can be loculated and associated with dense adhesions. An alternative and less invasive method that can be used to completely evacuate purulent effusions, thus controlling sepsis and avoiding the evolution to constrictive pericarditis, consists of pericardial drainage associated with intrapericardial infusion of streptokinase. Fibrinolytic therapy can enhance removal of material that would otherwise be too viscous or particulate to be removed by tube drainage. This treatment should be considered before undertaking surgery. Pericardiocentesis with a diagnostic purpose is not justified in the majority of cases for the following reasons: its low diagnostic power; the underlying pathology is often already known or identifiable by different noninvasive test; viral pericarditis is usually self-limiting and only requires an antiinflammatory treatment.

Pericardiocentesis with a diagnostic purpose is not justified in the majority of cases for the following reasons: its low diagnostic power; the underlying pathology is often already known or identifiable by different noninvasive test; viral pericarditis is usually self-limiting and only requires an antiinflammatory treatment.Contraindications

Anatomy

Anatomy

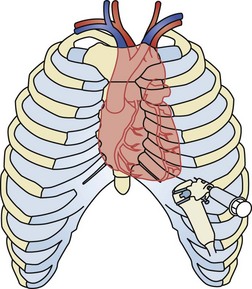

The pericardium is a fibroserous sac that contains the heart and the origin of the main vessels. It is composed of a fibrous outer layer and an inner serous membrane consisting of a single layer of mesothelial cells. The pericardial space normally contains 25 to 50 mL of fluid in adults. If the amount of fluid increases, the pericardium is not immediately distensible, even though stress relaxation may occur within minutes from the beginning of the increase in pericardial pressure. If the fluid accumulates slowly over weeks or months, the pericardium can increase in size to a maximum capacity of 1 to 2 L. The heart, and therefore the pericardium, is located at the center of the mediastinum, partially covered by the lungs, sternum, costal cartilages of the third, fourth, and fifth ribs, and by the intercostal muscles. About two-thirds of the heart is located on the left side of the chest. The heart rests on the diaphragm. The pericardium is innervated by the vagus nerve, the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, the esophageal plexus, and it also has rich sympathetic innervation from the stellate and first dorsal ganglia and the cardiac, aortic, and diaphragmatic plexuses. When performing pericardiocentesis, close attention should be paid to avoid damaging the internal thoracic artery, which runs behind the sternal end of the costal cartilages, and the vascular bundle at the inferior margin of each rib (Figure W9-1).

Procedure

Procedure

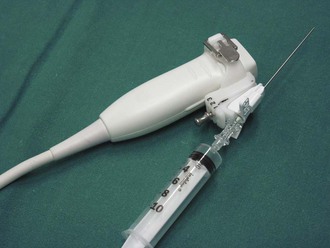

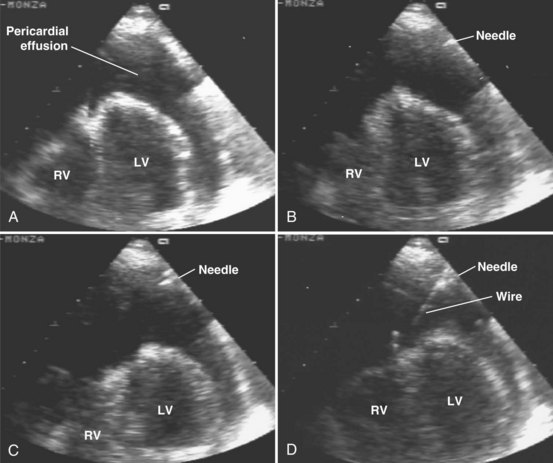

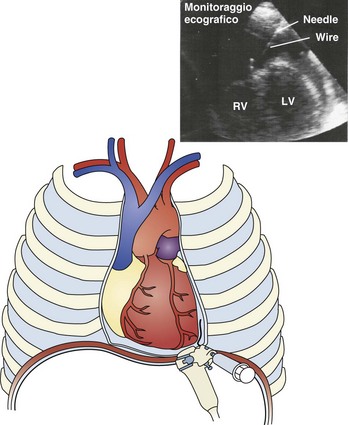

Echo-Guided Technique (A)

Procedure

Procedure

Echo-Guided Technique Under Continuous Visualization (This Technique Is Preferred by the Authors) (B)

After Procedure

After Procedure

Postprocedure Care

Outcomes and Evidence

Outcomes and Evidence

Roy CL, Minor MA, Brookhart MA, et al. Does this patient with pericardial effusion have cardiac tamponade? JAMA. 2007;297:1810-1824.

Mercè J, Sagristà-Sauleda J, Permanyer-Miralda G, et al. Correlation between clinical and Doppler echocardiographic findings in patients with moderate and large pericardial effusion: Implication for the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade. Am Heart J. 1999;138:759-764.

Maggiolini S, Bozzano A, Russo P, et al. Echocardiography-guided pericardiocentesis with probe-mounted needle: report of 53 cases. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2001;14:821-824.

Tsang TS, Enriquez-Sarano M, Freeman WK, et al. Consecutive 1127 therapeutic echocardiographically guided pericardiocentesis: clinical profile, practice patterns, and outcomes spanning 21 years. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:429-436.

Soler-Soler J, Sagristà-Sauleda J, Permanyer-Miralda G. Management of pericardial effusion. Heart. 2001;86:235-240.

Mercé J, Sagristà-Sauleda J, Permanyer-Miralda G, et al. Should pericardial drainage be performed routinely in patients who have a large pericardial effusion without tamponade? Am J Med. 1998;105:106-109.

Permanyer-Miralda G. Acute Pericardial disease: approach to the aetiological diagnosis. Heart. 2004;90:252-254.

Seferović PM, Ristić AD, Imazio M, et al. Management strategies in pericardial emergencies. Herz. 2006;31:891-900.

Sagristà-Sauleda J, Angel J, Sambola A, et al. Low pressure cardiaca tamponade. Circulation. 2006;114:945-952.

Vaitkus PT, Herrmann HC, LeWinter MM. Treatment of malignant pericardial effusion. JAMA. 1994;272:59-64.