12 Perianal pain

Case

Mrs JS is a 35-year-old woman who presents with severe anal pain on defecation. The pain had worsened over the previous 6 months. On further questioning she admitted to straining at stool, and the stool was sometimes hard and pellet-like. Her pain occurred spontaneously when sitting but was greatly exacerbated while passing a stool and lasted up to an hour. As a result, she was reluctant to pass stool and often held back passing a motion for 2 or 3 days. She noted bright blood on the toilet paper intermittently. She had also noted a small swelling at the anus but was not aware of any prolapse during defecation. She had a background history of two normal vaginal deliveries, without a perineal tear or episiotomy. She was otherwise fit and healthy. Abdominal examination was normal. On anal examination there was a fissure posteriorly in the midline with a sentinel tag. On gentle digital examination she was exquisitely tender posteriorly just within the anal verge, and no further internal examination or proctoscopy was carried out. There was no perianal inflammation, swelling or tenderness.

The fissure healed and her symptoms resolved. However she again returned after 3 months with a recurrent fissure, producing sufficient pain to cause her to miss days off work. She was advised to undergo lateral sphincterotomy, after providing clear information about the small risk of permanent faecal incontinence (usually minor). After undergoing anal manometry and endoanal ultrasound to confirm that anal sphincter function had not been affected by her vaginal deliveries (and hence place her at increased risk of incontinence after sphincterotomy), she underwent sphincterotomy under general anaesthetic. The fissure healed fully, with complete resolution of pain.

History

Symptoms of constipation are commonly associated with a number of painful perianal conditions (Ch 11). In some cases the constipation leads to the condition, such as fissures or haemorrhoids, but in other cases of anal fissures or thrombosed haemorrhoids the constipation may be caused by the patient’s reluctance to defecate because it induces or exacerbates pain. The conditions causing perianal pain should not themselves be associated with diarrhoea. Therefore, the presence of diarrhoea suggests another disease process (e.g. Crohn’s disease).

Examination

Inspection

The easiest and most comfortable position for inspection is with the patient in the left lateral position with the hips and knees flexed. The buttocks are parted with gentle pressure from the palm of the hand so that the perianal skin can be closely examined. Red excoriated skin suggests that the pain is due to pruritus ani. The presence of a sinus means an anal fistula should be sought. The presence of a spot of pus or blood in the perianal region can point to the external opening of a fistula. A perianal abscess can be associated with a perianal swelling and redness of the overlying skin, depending upon the proximity of the abscess to the external skin.

Proctoscopy

Proctoscopy will be possible in an office setting for most patients (Ch 22). It will not be possible in patients with an anal fissure, anal abscess or thrombosed haemorrhoids. Proctoscopy will allow a diagnosis of internal haemorrhoids, which will become more prominent or evident as the proctoscope is withdrawn.

Fissure-in-Ano

Aetiology

Secondary fissures are caused by Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, immunosuppression (e.g. chemotherapy or HIV infection) and, rarely, tuberculosis or syphilis.

Pathology

The acute fissure is a superficial split with soft edges.

A chronic fissure evolves through several phases:

Clinical features

Examination

A small proportion of primary fissures are not associated with internal sphincter spasm, particularly postpartum fissures. However, if spasm is not present underlying pathology (secondary fissure) should be suspected. A sigmoidoscopy should then be done to look for evidence of proctitis. Serum should be collected for HIV and syphilis serology, when indicated.

Treatment

Surgery

Surgery is indicated only if the fissure fails to heal and remains painful despite all the above measures, because a small percentage of patients will develop faecal incontinence after sphincterotomy. The basis of surgical treatment is to disrupt the spasm in the lower part of the internal anal sphincter. Anal dilatation successfully achieves this aim but can lead to incontinence in up to one-quarter of cases, and has therefore been abandoned in favour of the more controlled method of sphincter division (sphincterotomy). Sphincterotomy was initially performed posteriorly together with excision of the fissure, but this may cause fibrosis and a keyhole deformity with resultant seepage of stool. Sphincterotomy is therefore now carried out laterally. It may be done as a closed or open technique, and the recurrence rate is less than 2%. Anal physiology tests (see Ch 16) should be performed in all patients who have had prior anal surgery, particularly multiparous women. Sphincterotomy should be avoided in those patients with low anal canal pressures. In these patients advancement flaps may be considered as an alternative treatment.

Anal Sepsis

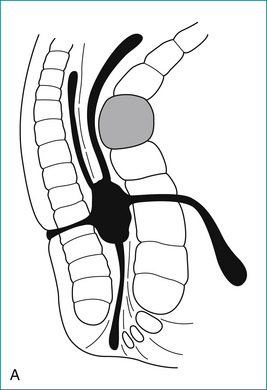

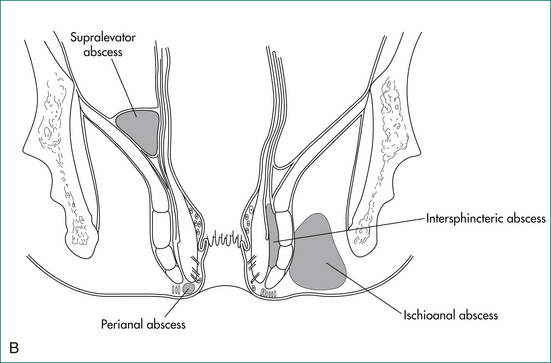

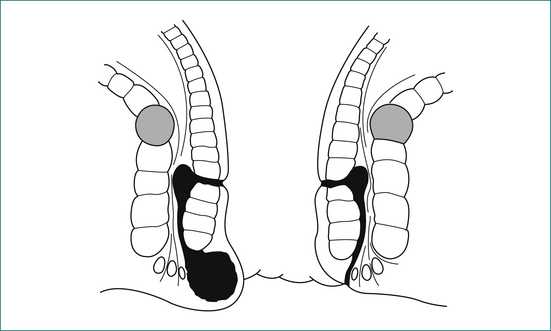

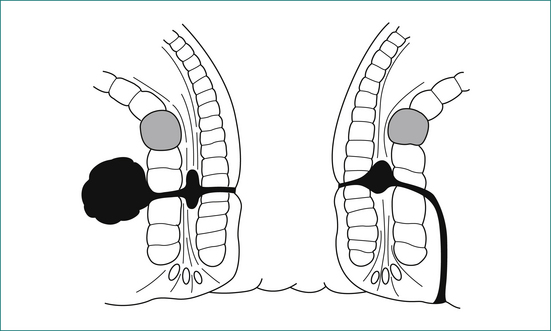

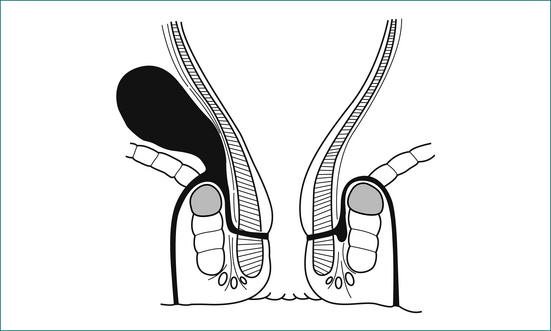

The majority of cases of anal abscess develop from a primary infection in an anal gland (Box 12.2). This infection results in the formation of an abscess in the intersphincteric space, which in turn may spread to form a perianal abscess, ischiorectal abscess or supralevator abscess. If an abscess communicates with the anal canal, and also discharges or is surgically drained through the perianal skin, a fistula has formed. Anal abscess and fistula are therefore part of the same pathological process.

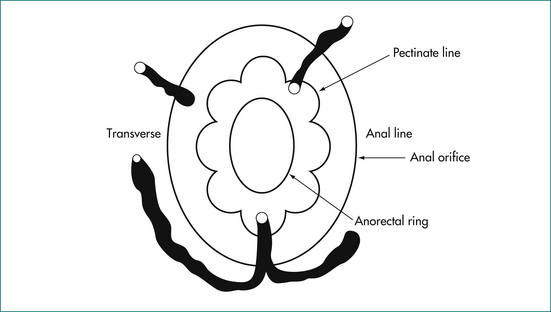

Anatomy

The anal canal is surrounded by two concentric muscle rings. The inner circular layer (internal anal sphincter) consists of smooth muscle, and is formed from the downward continuation of the circular muscle of the rectum. The outer layer (external anal sphincter) consists of striated muscle and is the muscle under voluntary control; it is continuous at its upper border with the levator ani muscle. The space immediately above the levator ani is called the supralevator space. The space between the internal and external sphincters is called the intersphincteric space. On the outer side of the internal sphincter is a layer of longitudinal smooth muscle, which is the downward continuation of the longitudinal muscle of the rectum. This muscle sends strands laterally through the external sphincter to reach the ischiorectal fossa, and infection may spread along this plane.

Pathology

Primary anal gland (cryptoglandular) abscess and fistula

A cryptoglandular abscess should be distinguished from:

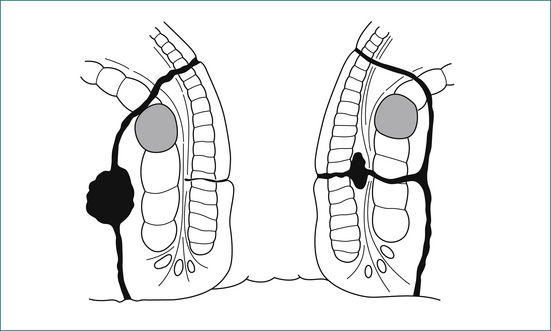

A cryptoglandular abscess may progress to form a fistula of the following type:

Secondary abscess and fistula

The features of these are as follows:

Clinical features

The cardinal feature of an anal abscess is severe pain. A perianal abscess usually causes a tender red swelling near the anal verge (see Fig 12.7).

Usually the external opening of a fistula is easily identified. The position should be noted in order to predict where the internal opening will be found (see Fig 12.8).

Supralevator extension is easily palpated on digital examination (see Fig 12.9).

Principles of surgical treatment

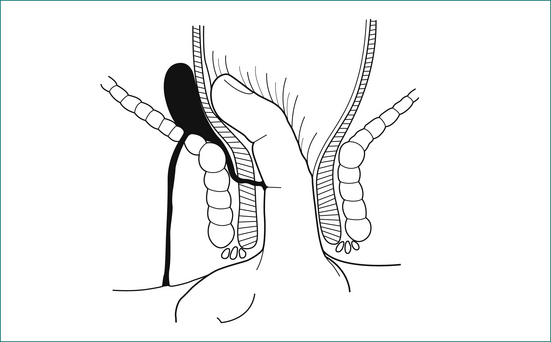

An intersphincteric or trans-sphincteric fistula can be laid open if there is sufficient muscle remaining above the fistula track. If the track is too high, or if it is suprasphincteric or extrasphincteric, it should be treated either by placing a flap of mucosa and internal muscle to close the internal opening of the fistula, or alternatively with a Seton technique, where a rubber drain is placed around the fistula and gradually tightened (Fig 12.10).

Haemorrhoids

Anatomy

The submucosa of the anal canal is expanded at three sites to form the submucosal cushions, located in the 3, 7 and 11 o’clock positions. The submucosa is supported by muscle fibres of the musculus submucosae ani. Within the submucosa is a plexus of vessels that joins arteries to veins without capillaries. This plexus of vessels is called the internal haemorrhoidal plexus above the dentate line, and the external haemorrhoidal plexus below the line in the lower anal canal and anal verge.

Pathophysiology

The anal cushions are central to the development of haemorrhoids. During normal defecation there is a slight downward movement of the cushions together with their submucosal vasculature. If there is excessive prolapse or pressure on the cushions, such as occurs with prolonged straining at stool or with hard stools, the cushions become oedematous and the submucosal vascular plexus becomes engorged. Damage to the musculus submucosae ani caused by chronic straining at stool results in loss of support of the anal cushions, which worsens the prolapse of the cushions. In addition, in the majority of patients with haemorrhoids there is a hypertonic internal sphincter muscle, producing very high intra-anal canal pressure. This leads to trapping of the prolapsing anal cushions outside the sphincter. All these factors result in progressive prolapse, oedema and engorgement of the submucosal plexus of vessels, with rupture of the vessels connecting arteries directly to veins. Bleeding then is bright red.

Clinical features

Prolapse

Haemorrhoids are classified according to the degree of prolapse of the anal cushions:

Thrombosed haemorrhoids

Prolapse beyond the anal sphincter may result in thrombosis. There is swelling and severe pain. The prolapsed haemorrhoids are easily visible and very tender (see Fig 12.12).

Figure 12.12 Irreducible fourth degree haemorrhoids. Note the left lateral pedicle (centre), which is thrombosed.

If thrombosed haemorrhoids are not treated surgically there is usually gradual resolution, but pain may persist for up to 2–4 weeks. Necrosis and infection may result. Most patients will be treated symptomatically with stool softeners and oral (non-constipating) medications, and once the thrombosed sections have resolved rubber banding to the internal haemorrhoids should be carried out, usually after 6–8 weeks (see below). Occasionally, thrombosed haemorrhoids may return into the anal canal and are not visible externally, but if thrombosis is established, severe pain persists and a tender lump is palpated on digital examination.

Thrombosed external haemorrhoids

This condition is quite different from thrombosed internal haemorrhoids. It occurs as a result of thrombosis of the lower part of the external haemorrhoidal plexus of submucosal vessels. The term ‘perianal haematoma’ is often used but is technically incorrect, since the clot is contained within an endothelial-lined blood vessel and is therefore not a haematoma.

Pruritus Ani

Aetiology

The predisposing causes are as follows:

Management

Box 12.3 Instructions to patients with anal irritation (pruritus ani)

Chronic Perianal Pain Syndromes

Descending perineum syndrome

There are a variety of clinical conditions in which perineal descent and straining at stool are found, including haemorrhoids, neurogenic faecal incontinence, urinary stress incontinence, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, uterovaginal prolapse and rectocoele. This group of conditions arises as a result of a functional obstruction to rectal evacuation, which causes excessive straining during defecation.

Key Points

History

Allan A., Samad A.J., Mellon A., Marshall T. Prospective randomised study of urgent haemorroidectomy compared with non-operative treatment in the management of prolapsed thrombosed internal haemorrhoids. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:41-45.

Cross K.L.R., Massey E.J.D., Fowler A.L., et al. The management of anal fissures: ACPGBI position statement. Colorectal Disease. 2008;10(suppl 3):1-7.

Heard S. Pruritis ani. Aust Fam Physician. 2004;33:511-513.

Keighley M.R.B. Anorectal abscess. In: Keighley M.R.B., Williams N.S., editors. Surgery of the anus, rectum and colon. London: WB Saunders; 1993:397-417.

Lawler L.P., Fleshman J.W. Hemorrhoids. In: Pemberton J.H., Swash M., Henry M.M., editors. The pelvic floor: its function and disorders. London: WB Saunders; 2002:371-384.

Lubowski D.Z. Anal fissures. Aust Fam Physician. 2000;29:839-844.

Williams J.G., Farrands P.A., Williams A.B., et al. The treatment of anal fistula: ACPGBI position statement. Colorectal Disease. 2007;9(suppl 4):18-50.