CHAPTER 85 Percutaneous Disc Decompression

INTRODUCTION

An increase in intradiscal pressure resulting from age, disease, or injury may alter the balance between the mechanical, physical, chemical, and pharmacological factors that maintain the cellular activity and tissue morphology of the intervertebral disc resulting in disc protrusion, herniation, and eventual disc degeneration.1

Surgical treatment of intervertebral disc herniation such as open discectomy, microdiscectomy, and laminectomy are often targeted for patients with herniated, extruded, or sequestered discs. In contrast, patients presenting with a contained herniated disc, which has not responded to conservative, noninvasive treatment, are often not considered as surgical candidates. For such herniations, percutaneous disc decompression has been performed using a variety of chemical and mechanical techniques Different concepts of how these methods work have been proposed, including mechanical, chemical, and a mere placebo effect.2,3 The mechanical concept is based on reduction of the intradiscal pressure with successive relief of the pressure of the nerve root or the pain receptors around the disc. Chemonucleolysis, percutaneous nucleotomy, percutaneous discectomy, and laser treatments incorporate this approach, and all have been shown to reduce intradiscal pressure. However, each treatment has its limitations, and success rates vary considerably. The indications for each of these technologies is identical.

There has been no reported permanent nerve injury or great vessel damage with these techniques. In contrast, open surgical procedures have a small yet palpable risk of a major adverse event. Ramirez and Thisted4 reported that in 28 000 open discectomies, there was a major complication in 1 in 64 patients, neurological complication in 1 in 334 patients, and 1 in 1700 patients died from the procedure. Pappas et al.5 reported outcome analysis in 654 surgically treated lumbar disc herniations; there were two major vascular injuries, one of which resulted in death. It seems that the safety profile of percutaneous disc decompression is superior to that of open surgery.6

CHEMONUCLEOLYSIS

Introduction

Chemonucleolysis is a medical procedure that involves the dissolving of the gelatinous cushioning material in an intervertebral disc by the injection of an enzyme such as chymopapain. In 1956, Thomas7 injected papain into the vein of a rabbit’s ear, observed the floppiness of that ear (compared with the erect state of the control ear), and confirmed softening of the cartilage attributable to papain.

Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain was introduced by Smith and Brown8,9 in 1964 as an effective therapy for some types of intervertebral disc herniation. However, because of the protein nature of chymopapain, anaphylactic reactions and neurotoxicity have limited the use of this therapy. Although it has demonstrated long-term success rates between 66% and 88%,10,11 a controlled study initiated by the US Food and Drug Administration12 (FDA) found chymopapain no more effective than placebo. Though it has become commercially unavailable in the US, it is still widely used outside of the US.

Two enzymes have been described as effective when used in vivo: chymopapain, which catalyzes the hydrolytic cleavage of glycosaminoglycans from proteoglycan aggregates in the disc, and collagenase, which splits the type 2 collagen fibers with relative particularity. The basic collagenase enzyme synthesized by Clostridium histolyticum consists of varied subenzymes that split the collagen fibers at different locations. The purified collagenase is relatively specific for type 2 collagen, seen mainly in the nucleus pulposus, which consists of 15–20% collagen in its dry weight. Wittenberg et al.13 did a 5-year clinical follow-up assessment of a prospective, randomized study of chemonucleolysis using chymopapain (4000 IU) or collagenase (400 ABC units). At 5 years, good and excellent results were observed in 72% of the chymopapain group and 52% of the collagenase group.

If conservative treatment in patients with recurrent disc herniation after chemonucleolysis fails, surgery is usually recommended. Historically, a second injection was considered contraindicated because of the fear of allergic or anaphylactic reactions. Schweigel and Berezowskyj14 suggested a second injection of chymopapain generally is contraindicated. They observed five major anaphylactic reactions in a review of 35 patients. Due to the high incidence of anaphylaxis, they considered repeat use of chymopapain to be an unacceptable alternative to surgery until a definitive test for chymopapain sensitivity is available.

Sutton15 did not observe an anaphylactic reaction when patients were premedicated with histamine receptor blockers. The effect of histamine, released by the immunoglobulin E mediated mast cells, will be blocked. Van de Belt et al.16 reviewed 85 patients who received a second injection of chymopapain because of a recurrent disc herniation between 1980 and 1996. All patients were pretreated for 3 days with H1 and H2 receptor blockers. Immediate sensitivity reactions were not seen. Four type 1 and one type 2 reactions were seen after the second injection, and no other complications were seen.

Age can be a factor in choosing patients for chemonucleolysis. Patients older than 60 years may lack sufficient mucoprotein in the offending disc to be hydrolyzed. Patients younger than 20 years have not been studied as frequently as older patients, but 80–90% satisfactory results are reported even though stiffness of the back may persist for a year or more. Single-level involvement with leg pain greater than back pain, corroborative physical findings, and imaging studies represent the ideal chemonucleolysis candidate.17 A successful intervention depends on the chymopapain reaching the mucoprotein of the herniated nucleus pulposus to hydrolyze it, so there must not be a sequestrated fragment surrounded by fibrosis or a posterior ligament defect closed by fibrosis to prevent the enzyme reaching an extrusion. If the offending herniation is primarily composed of annular tissue, its collagenous content will not be reduced by chymopapain. Spinal stenosis, whether central or lateral, may be exacerbated by chemonucleolysis rather than helped. Deburge et al.18 reported lateral recess stenosis in 16 patients and two cases of sequestrated discs in 38 patients who had not been successfully treated with chymopapain.

For the diagnosis of disc abnormalities, MRI is superior to CT scan However, MRI is not as effective in the diagnosis of bony lesions, which makes CT scan essential in the preoperative evaluation of chemonucleolysis. With CT scan, information regarding chronic degenerative disc abnormalities, such as lateral recess stenosis and facet hypertrophy, as well as bony spurs and calcified discs, may be obtained. If a soft protrusion is demonstrated without spinal stenosis on CT scan, the success rate is expected to be better (Table 85.1).19

| ABSOLUTE | |

| Allergy to chymopapain or papaya derivatives | |

| Central/lateral spinal stenosis | |

| Cauda equina syndrome | |

| Sequestered disc fragment | |

| Fibrosis due to prior surgery | |

| Failed back surgery syndrome | |

| Arachnoiditis | |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Pregnancy | |

| Profound or rapidly progressive neurological deficit | |

| Severe spondylolisthesis | |

| Spinal cord tumor | |

| Spinal instability | |

| RELATIVE | |

| Polyneuritis of diabetes | |

| Hypertension | |

| Morbid obesity | |

| Stroke | |

| Patients on beta blockers are at increased risk, should anaphylaxis occur, because beta blockade inhibits the effects of epinephrine | |

Complications

Between 1982 and 1991, 121 adverse events in 135 000 patients were reported to the FDA and investigated. Seven cases of fatal anaphylaxis, 24 infections, 32 bleeding problems, 32 neurological events, and 15 miscellaneous occurrences were found. The overall mortality rate was 0.019%.17 A major disadvantage of chemonucleolysis is the occurrence of back spasm, which can be quite severe in approximately 10% of patients.17 Comparing the complications of laminectomy reported by Ramirez and Thisted.4 in 1989 with those of chemonucleolysis, Nordby et al.17 reported that he found anaphylaxis to be unique to chemonucleolysis; infection occurred 17 times as often with laminectomy as with chemonucleolysis, neurologic and hemorrhagic events six times as often with laminectomy, and mortality rates incidental to the procedures occurred three times as frequently with laminectomy. Other potential complications include overdecompression, disc collapse, or instability of the motion segment. These side effects can result from excess ‘digestion’ of disc material. More serious complications have been reported, including lumbar subarachnoid hemorrhage and paraplegia. When chymopapain is inadvertently injected into the subarachnoid space, a cauda equina syndrome results.20 Wittenberg et al.13 reported cauda equina syndrome in two patients using collagenase. A case of acute transverse myelitis (ATM) was observed 21 days after an injection in 1982, and an additional five cases were subsequently reported to the FDA.21 Since no case of ATM has occurred in nearly 60 000 cases since 1984, an association between ATM and chemonucleolysis probably does not exist. Consequently, as of 1992, the FDA approved removing even the mention of ATM from the detailed chymopapain package Full Prescribing Information.21

Long-term results

Following chemonucleolysis, relief of leg pain is immediate; however, in up to 30% of patients, maximal relief of symptoms may take up to 6 weeks. There are some specific measures that can be utilized during chemonucleolysis to reduce the incidence of low back pain which includes infiltrating the needle track with local anesthetic and the use of antiinflammatory medications after the procedure.22

A prospective, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter, crossover trial of 88 patients demonstrated a 73% success rate in the chemonucleolysis group and a 42% success rate in the placebo group The failures in the placebo group later underwent chemonucleolysis and had a 90% success rate.23 The primary end point for considering a patient a failure was if the patient had pain severe enough to consider another intervention for treatment.

Nordby et al.17 reported that in a 7–10-year follow-up of 3130 patients with chemonucleolysis, overall satisfactory results were reported from 71–93% among the 13 contributors for an average of 77%. The use of chymopapain has been greater in Europe and Australia than in the United States since the acute transverse myelitis scare, and intrathecal complications have been rare there. A combined long-term report of 1736 patients in 1992 from the United Kingdom, France, and Germany showed good to excellent results of 66–84%, with an overall average of 75.3%. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy (APLD) to chemonucleolysis for the treatment of sciatic pain reported a 1-year outcome of 66% success in the chemonucleolysis group and 37% in the APLD group.24

The most compelling evidence that chemonucleolysis is a safe and effective treatment for herniation of the nucleus pulposus is found in well-designed and conducted prospective, randomized, double-blind studies in the United States and Australia.25 One of these double-blind studies has been carried through for 10 years without code break or loss of follow-up. Success persisted in 77% of patients with chemonucleolysis compared with only 38% for the placebo group (p=0.004). Only six of the patients with chemonucleolysis had required laminectomy compared with 14 in the placebo group (p=0.028).

Launois et al.26 reported the success rate at 1 year for chemonucleolysis at 88% and for laminectomy at 76%. Chemonucleolysis continued to be superior to surgery after an additional year. In a 9–11-year prospective, randomized study comparing patients with these two methods, Wilson et al.27 concluded that ‘surgically treated patients that had done well initially deteriorated with time, whereas those who did well following chemonucleolysis maintained a successful outcome in the long-term cost savings.’ A major consideration in cost savings is the absence of epidural scarring or adhesive arachnoiditis with chemonucleolysis, thus avoiding the frequent ‘failed back syndrome’ seen with laminectomy, which has become an ever-increasing health and economic burden.28 When the results of surgery after chemonucleolysis failure were compared with the results from microdiscectomies performed without prior injections, slightly more good and excellent results were observed in the primary surgery patients.29

Other authors such as McCulloch and MacNab30 stated that open surgery was easier after prior chemonucleolysis.

Norton31 obtained very poor results in patients treated either surgically or with chymopapain. All of his patients were claiming workmen’s compensation. Others have shown that on treatment with chymopapain such patients do not respond as well as those who are more highly motivated and covered by private insurance.

Nordby and Wright32 reported that 45 studies were analyzed, some including comparisons of chemonucleolysis to open laminectomy/discectomy and others to percutaneous discectomy. Individual success rates exceeded 60%, whereas cohort total averaged 76%. In studies comparing chemonucleolysis with open discectomy, success rate averaged 76.2% as compared with 88% for open surgery. In two other studies, percutaneous discectomy was less successful than chemonucleolysis. Where included, duration of hospitalization showed less time and thus less costs for chemonucleolysis. Return to work compilations showed time off slightly less for chemonucleolysis than for laminectomy.

Wittenberg et al.13 reported a 5-year clinical follow-up assessment of a prospective, randomized study of chemonucleolysis using chymopapain (4000 IU) or collagenase (400 ABC units); patients in the chymopapain group started work in the same job an average of 8 weeks after injection, whereas patients in the collagenase group returned to work after an average of 11 weeks.

Kim et al.19 reported that three thousand patients with herniated lumbar disc were treated with chemonucleolysis between 1984 and 1999 and found that the clinical success rate in their series was 85%. The patient group with the chief complaint of leg pain achieved a better clinical outcome than the patient group with low back pain (88% versus 59%), and a positive straight leg raising test was strongly correlated with good clinical outcome. Patients manifesting a soft, protruded disc had a better outcome than those manifesting diffuse bulging disc. Other prognostic factors favoring a good outcome were young age, short duration of symptoms, and no bony spur or calcification on radiological study.

Revel et al.33 conducted a randomized clinical trial to compare the results of automated percutaneous discectomy with those of chemonucleolysis in 141 patients with sciatica caused by a disc herniation; 69 underwent automated percutaneous discectomy and 72 were subjected to chemonucleolysis. The principal outcome was the overall assessment of the patient 6 months after treatment. Treatment was considered to be successful by 61% of the patients in the chemonucleolysis group compared with 44% in the automated percutaneous discectomy group. At 1-year follow-up, overall success rates were 66% in the chemonucleolysis group and 37% in the automated percutaneous group. Within 6 months of treatment, 7% of the patients in the chemonucleolysis group and 33% in the discectomy group underwent subsequent open surgery. The complication rates of both treatment groups were low, with the exception of a high rate of low back pain in the chemonucleolysis group (42%). In another prospective study, 22 patients with painful disc herniations were randomized either to chemonucleolysis or APLD; at 2 years the chemonucleolysis-treated patients were significantly better, based upon outcomes as measure with the Oswestry Disability Index, back pain and leg pain recurrence.34

The combination of low-dose chemonucleolysis with 500 IU chymopapain followed by an automated percutaneous nucleotomy of the cervical spine has been performed. A follow-up of at least 1 year of the first 22 patients showed in 19 patients good or excellent results. In one patient a fair result was obtained and in two patients the symptoms were unchanged.35

AUTOMATED PERCUTANEOUS LUMBAR DISCECTOMY

Introduction

In 1975, Hijikata et al.2 performed the first percutaneous discectomy using modified pituitary rongeurs. A decade later in 1985, Onik and colleagues24 developed the nucleotome, an automated suction shaver that allows for the performance of an automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy (APLD). The shaver functioned by drawing the nucleus pulposus into a small cutting port and eliminated a portion of the nucleus via a reciprocating ‘guillotine-like’ blade. APLD utilized a 20.3 cm needle inserted through a 2.8 mm diameter cannula. Onik and Helms36 reported an 85% success rate independent of the amount of disc material removed. It is believed that the removal of nuclear material from the center of the disc results in disc decompression. Ultimately, it is believed this decreases pressure transmitted through the rent in the anulus to the herniation. This results in decreased pressure on the affected nerve.

Indications

Different morphological and pathophysiological parameters are used to define criteria for selecting candidates for APLD. Some clinicians stress the value of CT discography. Mochida and Arima37 demand the absence of perforation of the posterior longitudinal ligament and degenerative canal stenosis detected by CT or MRI along with other clinical guidelines including age and disturbance of innervated muscles.

APLD is efficacious for patients whose herniations are still contained by the anulus or the posterior longitudinal ligament. Patients with sequestered fragments are not candidates because there is no biomechanical mechanism by which that fragments would be resorbed. MRI can be extremely helpful in excluding obviously migrated fragments and large disc extrusions.36 An absolute contraindication of APLD is the migration of a disc fragment. When small degrees of migration are present (3 mm or less) the possibility of a good result from APLD is not precluded. The success rate for APLD is about 43% in those patients who had fragments that migrated more than 3 mm from the disc space. In a study by Carragee and Kim examining outcomes of open discectomy, it had been shown that herniations larger than 6 mm generally did well with discectomy, whereas smaller herniations were associated with a poor outcome (26% success).38 These studies suggest that patients with smaller herniations are ideal candidates for APLD and probably with other techniques that effect percutaneous disc decompression.

A CT discogram is the most definitive procedure for selecting patients for APLD which demonstrate complete tears of the anulus and posterior longitudinal ligament. A CT discogram also allows the assessment of the size of the rent in the anulus that is communicating with the herniation. Besides the characterization of the herniation on imaging studies, patients should clinically have the symptoms of radiculopathy.36 APLD is not a procedure for those patients with vague or equivocal symptoms or simply a bulging disc. APLD can be an excellent procedure for patient who has had a reherniation at the site level of previous disc surgery. These patients who are reoperated at the same level obtain lower success rates, as well as being exposed to a much higher morbidity due to lack of tissue planes caused by epidural fibrosis. APLD takes a posterolateral course that avoids the epidural space and does not create epidural fibrosis. Mirovsky and Neuwirth39 reported 10 patients with lumbar disc reherniation at the same level as a previously open operation with follow-up of 2.5 years They report that 70% of their patients showed complete or significant pain relief avoiding reoperation. Sixty percent showed motor deficit improvement. Failure was primarily relegated to those with spinal stenosis or segmental instability.

Onik et al.40 reported that patients whose herniations occur in the lateral location beyond the intervertebral foramen are candidates for APLD. Such patients are difficult to treat with the traditional interlaminar approach of microdiscectomy, which requires the removal of all or a large portion of the facet. APLD showed excellent results in those patients because the percutaneous discectomy instrumentation drives over the herniation itself. The poor results occurred in patients with concomitant stenosis.41

ALPD can be the procedure of choice for those patients suspected of infectious discitis. The first principles of treatment for disc space infection are to make the diagnosis and isolate the organism. Diagnosis may be delayed because patient’s complaints are relatively non-specific. Imaging studies may direct one to the diagnosis, but tissue must be obtained for the confirmation and isolation of the organism. APLD biopsy is a minimally invasive procedure for obtaining sufficient material for histological analysis and culture. The rate of secondary surgical intervention may be reduced if infected disc material is removed by percutaneous biopsy; however, surgical treatment is indicated in all patients who develop neurological deficits as well as in the presence of epidural or retroperitoneal abscess.42 Gebhard and Brugman43 reported a case in which nucleotome was used to remove 5 ml of disc material and the disc space was irrigated with 75 ml of normal saline containing cefazolin, the patient reported immediate relief of his back and thigh pain. Fouquet et al.44 obtained bacteriologic diagnosis in only nine of 25 patients biopsied with a Mazabraud trocar. Krodel et al.45 reported seven positive cultures of 15 patients who underwent needle biopsy. Yu et al.46 described two cases in which automated biopsy was used to diagnose unusual infections include Candida discitis and tuberculosis.

Percutaneous discectomy has been used also in the treatment of cervical disorders. Theron et al.,47 in 1992, reported preliminary experience in 23 cases. All patients complained of neck pain or brachialgia due to single, soft herniated disc at a single level; the success rate was 80%. They later reported 78 treated cases, including 68 with follow-up of at least 6 months and overall success rate of 70.6%, and no complication was reported (Table 85.2).

| ABSOLUTE | |

| Cauda equina syndrome | |

| Sequestered disc fragment | |

| Arachnoiditis | |

| Pregnancy | |

| Profound or rapidly progressive neurological deficit | |

| Severe spondylolisthesis | |

| Bleeding dyscrasia | |

| Spinal instability or fracture | |

| Spinal tumor | |

| RELATIVE | |

| Previous open surgery at proposed treatment level | |

| Central stenosis | |

| Significant bony spurs that could block percutaneous entry into the disc space | |

Complications

Complications result from periprocedural issues or from the technique. Periprocedural complications may involve adverse reactions to anesthetic, sedative/analgesic medications, perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis, or intravenous fluid management. Technique-related complications include nerve root injury, discitis, osteomyelitis, cellulitis, uncontrolled bleeding, dural puncture, annular injury, and vertebral endplate injury. Matsui et al.48 reported a rare complication of a case of lateral disc herniation which occurred soon after percutaneous discectomy. In that case, it appeared that the extrusion occurred through the hole in the anulus made during the procedure.

Long-term results

Mochida and Arima37 reported that the postoperative pain relief and patient satisfaction that can be achieved by APLD is related to patient age, motor function of the lower limbs, and the length of preoperative conservative treatment. Hijikata49 reported poorer results at the level L5–S1. Others reported that the only significant predictive factor for a positive outcome with respect to pain relief and satisfaction was age. Outcome is also influenced by physical activity. Patients who are active in sports are significantly more satisfied compared to patients who are not, but sporting activity is not in itself a predictive factor for a positive outcome.50

Sahlstrand and Lonntoft51 evaluated the size of the disc herniation with MRI before, on the day, and 6 weeks after APLD and compared the MRI findings with the early clinical outcome. The development of pain, nerve root tension sign, and neurological findings were analyzed and no significant difference in the maximum protrusion of the disc herniation among the three measurements was reported. The sciatic pain improved significantly on the first day after the procedure, but not at 1 week or 6 weeks after the procedure. There was no correlation between the MRI findings and the early clinical outcome.

It has been reported that with APLD approximately 2–7 g of human disc has been removed. The amount of disc material retrieved is superior to any the other methods of percutaneous discectomy. In a study by Chatterjee et al.52 comparing APLD with microdiscectomy for contained herniations, the microdiscectomy group had an 80% success rate. The risk of reoperation was reported by Bernd et al.50 to be 25% while Nachemson53 reports that 6.6% of patients in his study required reoperation. Stevenson et al.54 did a cost-effectiveness study of APLD versus microdiscectomy in the treatment of contained lumbar herniation in a randomized, controlled trial and found that APLD is less cost-effective than microdiscectomy.

PERCUTANEOUS LASER DISCECTOMY

Introduction

In 1984, percutaneous laser disc decompression was pioneered in America by Choy et al.,55,56 who were intrigued by the principle that a small change in volume in a contained area results in a large change in pressure. This pressure reduction was demonstrated by Choy and coworkers in 18 cadavers. They measured intradiscal pressure using a pressure transducer that was inserted into the lumbar discs. Afterwards, 1000 J from an Nd:YAG, 1.32-ym laser was delivered through a quartz fiber. The mean intradiscal pressure after loading (pre-treatment) was 2419 mmHg. After laser treatment, the mean pressure decreased by 1073 mmHg, a decrement of 44%.

The laser (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) transmits energy in the form of light. This light is transformed into heat, which can simultaneously cut, coagulate, and vaporize tissue. The primary advantage of laser energy is its ability to focus at a single point. Several types of laser are available. The most commonly used are the KTP laser (potassium-titanyl-phosphate), Nd:YAG (neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet) and Ho:YAG (holmium:YAG). The choice of laser type is dependent on the ability of energy to be delivered through a fiberoptics system, tissue absorption/ablation properties, and the amount of thermal generation and spread.57 Hellinger et al.58 reported that percutaneous laser discectomy with the Nd:YAG laser (1064 nm) markedly reduces the postoperative density by 20% in protrusion and extrusion of the intervertebral discs.

Percutaneous laser discectomy of the cervical disc herniation spine can be done under X-ray fluoroscopy. CT-guided technique also provides safe and accurate position of the needle tip during puncture of the needle on axial images, permitting accurate laser ablation of the intervertebral disc. The use of CT also avoids damage to adjacent and visceral structures since it is superior in spatial and soft tissue resolution to X-ray fluoroscopy (Table 85.3).59

Table 85.3 Contraindications for percutaneous laser discectomy

| ABSOLUTE | |

| Central stenosis | |

| Significant bony spurs that could block percutaneous entry into the disc space | |

| Facet hypertrophy | |

| Sequestrated disc fragment. | |

| Ruptured posterior longitudinal ligament (epidural leak of contrast medium in discography) | |

| RELATIVE | |

| Progressive neurological deficit | |

| Involvement in workers’ compensation cases | |

| Previous surgery at the same disc level | |

Ohnmeiss et al.57 found that patients who met the following criteria, which included leg pain, positive physical examination finding, discographic confirmation of contained disc herniation, and no stenosis or spondylolisthesis, found that the success rate was 70.7% and the success rate was only 28.6% among patients who did not meet all the criteria. The advantage of performing discography immediately before laser disc discectomy is that it could be performed through the same needle placement to be used for the laser discectomy. The advantage of performing discography 1 or more days prior the laser discectomy that it allows more time to evaluate the discogram results and increases the allotted time for a patient to consider alternative treatments.

The contraindications of this procedure are paralysis, hemorrhagic diathesis, spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis, previous surgery at the indicated level, significant psychological disorders, significant narrowing of disc space, and industrial injuries with monetary gain. For 2 weeks after the procedure, any position that could induce hyperkyphosis as well as athletic activities should be restricted.61 The use of percutaneous laser disc decompression for the treatment of erectile dysfunction caused by herniated disc disease has been reported in two patients.62 In addition to the early return of the erectile function in both patients, immediate pain relief was achieved in the second case. Follow-up visits confirmed continued normal sexual function and lack of pain.62

Complications

Choy et al. reported one case of discitis. Bosacco et al.63 reported one minor complication involving a single patient, who had acute urinary retension and reflex ileus, out of 63 patients who underwent laser disc decompression with KTP 532 laser. There were no complications involving infection, hematoma, neurological injury, myelitis, or great vessel disease. Nerubay et al.64 reported complications with symptoms and signs of root irritation in 4 of 50 patients who underwent CO2 laser discectomy which were probably caused by thermal damage to the root caused by warming the cannula. Ohnmeiss et al.57 reported one case of reflex sympathetic dystrophy and 12 cases of postoperative dysesthesia among 164 patients who underwent leaser disc discectomy. Hellinger65 reported bowel necrosis, subsequently requiring resection, resulting from inadvertent perforation of the anterior anulus and two cervical cases of infections with succeeding neurological deficits. In one case there was a reversible paresis of the arm and in the other case there was paraplegia. Hellinger and Hellinger describe their outcomes and complications in greater detail in Chapter 29.

Long-term results

The advantages of laser discectomy include short recovery time, it is performed under local anesthesia, it reduces the soft tissue and bone injury, there is no epidural fibrosis, lessened chance of creating instability since only a small amount of tissue is removed, and reduced missed time from work.57 Disadvantages include the relative expense of the procedure and inadequate temperature control causing nerve root, vertebral body, and endplate damage.73

Choy et al.67 reported the results of 333 patients in whom they performed laser discectomy with the Nd:YAG laser and obtained 78.4% good results and poor responses for 21.6%. One hundred and sixty patients experienced immediate pain relief during the procedure. Choy also reported in another study that there is no association between outcome and sex, age, duration of symptoms, or disc level.74

Liebler60 reported that the success rate of the KTP laser based on 2 years’ follow-up was 72% and the success rate with the Nd:YAG laser was very similar, at 70%. For all patients, the average overall pain index declined immediately after the procedure. Pain intensity had a tendency to decrease as the duration of the follow-up continued, but this was not the case for the neurological findings. There were no statistical differences noted in knee jerk, ankle jerk, pin prick and Lasague’s sign as a function of disc level and follow-up for all patients. Nerubay et al.66 reported the results of 50 patients in whom they performed laser discectomy with the carbon dioxide laser and obtained 74% good results.

Chronic effects of laser discectomy have been evaluated in animals. Using a CO2 laser for cervical discectomies in a canine model, Gropper et al.69 found that the disc, easily and safely ablated, was replaced by dense, fibrous tissue in 10 weeks. Using Ho:YAG laser, Black et al.70 noted a similar effect in pigs.

Laser discectomy yields results comparable to those of manual or automated percutaneous discectomy,47 but is considerably more expensive. Percutaneous laser nucleolysis can damage endplates from excess thermal energy,66 and also has been shown to be significantly less effective than chemonucleolysis.71 Dangaria72 reported 15 cases where laser was used as a second attempt to relieve the symptoms of lumbar disc herniation in patients having undergone prior percutaneous discectomy with unsuccessful outcome. He found that only three out of 15 patients had good results, while none had excellent results.

Chiu et al.73 reported that cervical discectomy with laser thermodiscoplasty is safe and effective for the treatment of cervical disc herniation. A 94.5% success rate was obtained in 200 patients selected through diagnostic MRI, CT, and electromyogram (EMG) correlated with signs and symptoms. Knight et al.74 also reported that cervical laser disc decompression produces sustained and significant clinical benefit in over 51% of patients observed for a mean period of 43 months. In a further 25%, functional benefit was achieved. Paresis, sensory deficits, neck pain, brachialgia, and headache improved considerably in most patients.

NUCLEOPLASTY (COBLATION)

Introduction

Coblation is a new minimally invasive procedure, using radiofrequency (RF) energy to remove nucleus material and create small channels within the disc. With coblation technology, RF energy is applied to a conductive medium, causing a highly focused plasma field to form around the energized electrodes. The plasma field is composed of highly ionized particles. These ionized particles have sufficient energy to break organic molecular bonds within tissue and form a channel. The by-products of this non-heat-driven process are elementary molecules and low molecular weight inert gases, which are removed from the disc via the needle. On withdrawal of the Perc-DC® Spine Wand, the newly created channel is thermally treated, producing a zone of thermal coagulation. Thus, nucleoplasty combines coagulation and tissue ablation to form channels in the nucleus and decompress the herniated disc. The temperature is kept below 70°C to minimize tissue damage. Unlike chemonucleolysis, nucleoplasty is not dose dependent, and pressure changes seem to occur quicker. Chen et al.75 assessed the intradiscal pressure change after disc decompression with nucleoplasty in human cadavers, and found that intradiscal pressure was markedly reduced in the younger, healthy disc cadaver. In the older, degenerative disc cadavers, the change in intradiscal pressure after nucleoplasty was very small. There was an inverse correlation between the degree of disc degeneration and the change in intradiscal pressure. The limitation of this study was that pressure measurements were performed on cadavers and not in vivo. Chen et al.76 also reported that after histological examination of disc and neural tissue in two pigs that underwent coblation there was no evidence of direct mechanical or thermal damage to the surrounding tissues and there were clear evidence of coblation channels with clear coagulation borders of the nucleus pulposus. Normal histological findings of the anulus and endplate with normal neural elements of the spinal cord and nerve roots at the level of the procedure were observed. Since its first application in July 2000, the DISC Nucleoplasty procedure has been used to treat over 55 000 patients in the USA and around the world.

Coblation can be performed from either side of the affected disc, not just from the ipsilateral, symptomatic side. Thus, treatment approaches are not limited to one site only.

Operative procedure using Perc-DC® for the cervical spine

Complications

It is therefore strongly recommended that the introducer needle and catheter position be checked prior to stimulating with coagulation. Prospective data on complications and side effects of lumbar nucleoplasty reported soreness at the injection site as the most common side effect, which dropped rapidly after the first 72 hours postprocedure. Numbness and tingling were the next most commonly reported side effects.77 Finally, it cannot be overemphasized that the most important issue to avoid serious postprocedure sequelae is physician experience. Cervical coblation is not for novices or those who have not performed in excess of 100 cervical discograms.

Long-term results

Slipman et al.78 reported their initial experience using nucleoplasty in five patients with cervical radiculopathy. All subjects showed 75% reduction in the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score at all follow-up intervals. Of five patients, four returned to full-time work within 2 weeks postprocedure. In another pilot study by the author,78a 20 consecutive patients with a mean age of 43.4 years were prospectively enrolled. All patients underwent cervical combined percutaneous plasma field discectomy and nerve root glucocorticoid injection. The average symptom duration preprocedure was 35.9 weeks. Each patient was deemed an appropriate operable candidate by the spine surgeon. The mean size of the focal protrusion was 3.6 mm and the mean size of the canal was 11.7 mm. There was a statistically significant VAS rating reduction at each follow-up (p<0.001), which transpired at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. The preprocedure VAS rating for the cohort was 7.0 and at each of the follow-ups it was 2.9, 2.1, 1.7, 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4. No significant early-term side effects were noted. Five patients experienced minor bleeding, which resolved by 72 hours. All patients experienced self-limited soreness at the procedure site. One patient underwent surgical intervention between 8 and 12 weeks, and returned to work pain free.

Derby et al.79 reported greater than 50% VAS improvement at 3 months’ follow-up in nine patients with neck or upper axial back pain who underwent nucleoplasty.

The results in controlled trials are total resolution of leg pain in 70% of cases and patient satisfaction after 6 months in around 80%.80,81

Nardi et al.82 reported the results of his prospective study in which 50 patients underwent cervical coblation. There results were compared to 20 controls. Unfortunately, the average follow-up interval was only 3.8 months (range 2–9 months). The coblation group achieved 80% success, while the controls 15%.

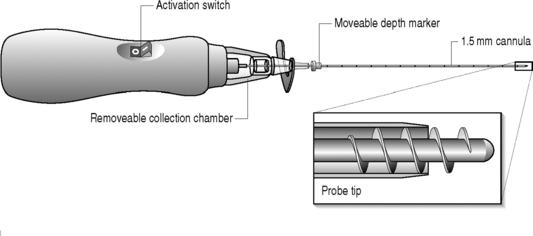

Percutaneous discectomy using the Dekompressor

The Dekompressor is a single-use disposable lumbar discectomy probe that passes through and works in conjunction with a 15 mm introducer cannula to remove intervertebral disc nucleus pulposus material (Fig. 85.1) It is manufactured by the Stryker Corporation and has been available for clinical use since 2004. Devices made for cervical and lumbar access vary by the length and/or width of the probe. The cervical device is 3.5 inches in length and is placed within a 19-gauge introducer needle The three lumbar dekompressors are 6 inches in length and inserted through a 17-gauge or 19-gauge introducer needle and the third is 9 inches in length and inserted into a 17-gauge needle, This array of lumbar devices allows for the treatment of thin through obese patients.

Technique

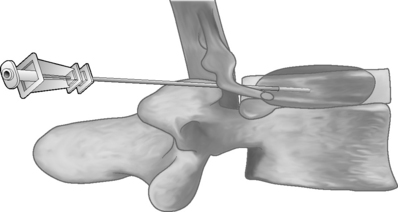

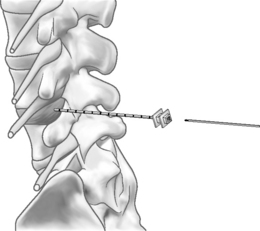

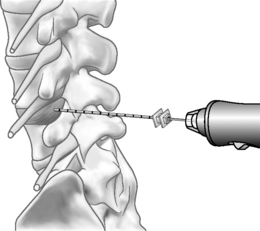

The Dekompressor is introduced into the disc in a similar fashion to performing nucleoplasty. A point of entry is established that allows the working device to traverse the longest possible length of the disc through an extrapedicular approach. The patient is placed in a left lateral decubitus position with a slight obliquity on a fluoroscopy table. As in all decompression techniques the patient is prepped and draped in sterile fashion. Conscious sedation is administered intravenously. Disc access via an extrapedicular approach is then gained using a 1.5 mm (17-gauge) Dekompressor cannula with stylet under fluoroscopic guidance. Once the cannula is in place, the stylet is removed and the probe (titanium auger) is introduced through the cannula into the disc (Figs 85.2–85.4). As part of the construction of the probe, the auger has been connected to a disposable rotational motor, which spins the probe. The rotational motion of this probe creates suction and removal of nucleus pulposus through the cannula using the Archimedes pump principle. The nuclear material collects along the length of the probe and in some instances reaches the collection chamber at the base of the probe. We perform two or three passes of the probe/introducer needle complex and then withdraw the probe. This allows us to check the amount of nuclear material removed. If there has not been sufficient material removed, the stylet is replaced into the introducer needle and placed in new position within the disc. Once sufficient nuclear material has been removed, the introducer needle/probe complex is gradually withdrawn and then discarded. Typically, we perform a therapeutic selective nerve root block at the affected nerve root.

Indications

Patients with lumbar radiculopathy due to contained focal disc protrusion or diffuse disc bulge/central focal protrusion causing spinal stenosis may be candidates for this procedure. In our experience, patients with disc extrusions are candidates as well.83

Outcomes

To date, only two articles have been published reporting outcomes.84,85 Amoretti et al.85 reported on 10 cases where 8 of 10 patients described 70% drop in VAS scores in follow-up ranging from 6 to 10 months. Alo et al.84 published a study in 2005 describing a cohort of 50 patients with lumbar radicular pain with 1-year follow-up data. Patients included in this study had to have history and physical examination evidence of lumbar radicular involvement with confirmation in the form of MRI or discography and diagnostic selective nerve root blocks. Eight of 50 patients were lost to follow-up. Of the remaining 42 patients, VAS (Visual Analogue Scale) scores dropped from an average of 79 before percutaneous discectomy to an average of 2.8 at 12 months. Reported patient satisfaction was 88.1% with patients reporting improved function and decreased medication usage. Slipman et al.83 is conducting a study using outcome measures of VAS, medication usage, and Oswestry Disability Index in patients with lumbar radiculopathy due to diffuse disc bulging causing central stenosis, contained focal protrusion, or disc extrusion. Inclusion criteria for this pilot study required corroborative history, physical examination, and MRI findings. If the examination did not provide objective correlative data, an electrodiagnostic study was performed. If that was negative, a diagnostic selective nerve root block was completed. If each of these criteria was met and there was failure of proper medical rehabilitation and interventional spine treatment, the patient was selected to be in the study. Preliminary results show that 41 of 47 patients remain in the study at 6 months. Of the six who have failed percutaneous discectomy with the Dekompressor, four patients went onto surgery, one to acupuncture, and one was successfully treated with pregabelin. One of the 41 patients had not been treated for radicular pain, but for weakness. This patient described a marked improvement in strength (3/5 preprocedure and 4+/5 postprocedure). For the remaining 40, the Oswestry Disability Index dropped from 47.2% before percutaneous discectomy to 23% at 6 months, representing a change in one full category of disability. The average preprocedure VAS was 7.3, and at 6 months it was 1.7. Seventy-five percent had a VAS of 2 or less. Medication usage diminished as well. The reduction in VAS, Oswestry, and medication usage was statistically and clinically significant for each.82 One-year data are in the process of being collected and it appears the results are stable.

1 Hutton WC, Elmer WA, Boden SD, et al. The effect of hydrostatic pressure on intervertebral disc metabolism. Spine. 1999;24:1507-1515.

2 Hijikata S, Yamagishi M, Nakayama T, et al. Percutaneous nucleotomy: a new treatment method for lumbar herniation. J Toden Hosp. 1975;5:39-44.

3 Delamarter R, Howard M, Goldstein T, et al. Percutaneous lumbar discectomy. preoperative and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1995;77:578-584.

4 Ramirez LF, Thisted R. Complication and demographic characteristics of patients undergoing lumbar discectomy in community hospitals. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:226-231.

5 Pappas CTE, Harrington T, Sonntag VKH. Outcome analysis in 654 surgically treated lumbar disc herniations. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:862-866.

6 Onik GM, Mooney V, Maroon JC, et al. Automated percutaneous discectomy: a prospective multi-institutional study. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:228-233.

7 Thomas L. Reversible collapse of rabbit ears after intravenous papain and prevention of recovery by cortisone. J Exp Med. 1956;104:245-252.

8 Smith L. Enzyme dissolution of nucleus pulposus in humans. JAMA. 1964;187:137-140.

9 Smith L, Brown JE. Treatment of lumbar intervertebral disc lesions by direct injection of chymopapain. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1967;49(3):502-519.

10 Mansfield F, Polivy K, Boyd R, et al. Long-term results of chymopapain injections. Clin Orthop. 1986;206:67-69.

11 Gogan WJ, Fraser RD. Chymopapain. A ten-year, double-blind study. Spine. 1992;1:388-394.

12 Poynton AR, O’Farrell DA, Mulcahy D. Chymopapain chemonucleolysis: a review of 105 cases. J Roy Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:407-409.

13 Wittenberg RH, Oppel S, Rubenthaler FA, et al. Five-year results from chemonucleolysis with chymopapain or collagenase a prospective randomized study. Spine. 2001;26(17):1835-1841.

14 Schweigel JF, Berezowskyj J. Repeat chymopapain injections. Spine. 1987;12:800-802.

15 Sutton JC. Repeat chemonucleolysis. Clin Orthop. 1986;206:45-49.

16 van de Belt H, Franssen S, Deutman R. Repeat chemonucleolysis is safe and effective. Clin Orthoped Rel Res. 1999;1(363):121-125.

17 Nordby EJ, Fraser R, Javid MJ. Spine update. Chemonucleolysis. Spine. 1996;21(9):1102-1105.

18 Deburge A, Rocolle J, Benoist M. Surgical findings and results of surgery after failure of chemonucleolysis. Spine. 1985;10:812-815.

19 Kim YS, Chin DK, Choy D. Predictors of successful outcome for lumbar chemonucleolysis: analysis of 3000 cases during the past 14 years. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(2):123-128.

20 Agre K, Wilson RR, Brim M, et al. Chymodiactin postmarketing surveillance: demographic and adverse experience data. Spine. 1984;9:479-486.

21 Javid MJ, Nordby EJ. Current status of chymopapain for herniated nucleus pulposus. Neurosurg Q. 1994;4:92-101.

22 Alexander AH. Chymopapain chemonucleolysis. In: Chapman MW, editor. Operative orthopedics. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1993:2787-2794.

23 Scwetschenau PR, Ramirez A, Johnson J. Double blind evaluations of intradiscal chymopapain for herniated lumbar discs: early results. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:622.

24 Onik G, Maroon J, Helms C, et al. Automated percutaneous discectomy: initial patient experience, work in progress. Radiology. 1987;162:129-132.

25 Gogan W, Fraser RD. Chymopapain. A 10 year double-blind study. Spine. 1992;17:388-394.

26 Launois R, Rebous-Marty J, Henrey B, et al. Cost-utility analysis after seven years of treatment of lumbar discal hernia. J Econ Med. 1992;10:307-325.

27 Wilson LF, Chell J, Mulholland RC. The long-term results of chemonucleolysis. Presented at the annual meeting of the European Spine Society, Cambridge, England, September 1992.

28 Javid MJ. Chemonucleolysis versus laminectomy: a cohort comparison of effectiveness and cost. Spine. 1995;20:2016-2022.

29 Krämer J, Wittenberg RH. Microdiscectomy for lumbar disc herniation. Orthop Traumatol. 1993;2:10-18.

30 McCulloch JA, MacNab I. Sciatica and chymopapain. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1983.

31 Norton WL. Chemonucleolysis versus surgical discectomy: comparison of cost and results in worker’s compensation claimants. Spine. 1986;11:440-443.

32 Nordby EJ, Wright PH. Efficacy of chymopapain in chemonucleolysis. Spine. 1994;19(22):2578-2583.

33 Revel M, Payan C, Vallee C, et al. Automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy versus chemonucleolysis in the treatment of sciatica. A randomized multicenter trial. Spine. 1993;18(1):1-7.

34 Krugluger J, Knahr K. Chemonucleolysis and automated percutaneous discectomy–a prospective randomized comparison. Internat Orthoped. 2000;24:167-169.

35 Hoogland T, Scheckenbach C. Low-dose chemonucleolysis combined with percutaneous nucleotomy in herniated cervical disks. J Spinal Disord. 1995;8(3):228-232.

36 Onik GM, Helms C. Nuances in percutaneous discectomy. Radiol Clin North Am. 1998;36:523-532.

37 Mochida J, Arima T. Percutaneous nucleotomy in lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 1993;18:2063-2068.

38 Carragee EJ, Kim DH. A prospective analysis of magnetic resonance imaging findings in patients with sciatica and lumbar disc herniation: correlation of outcomes with disc fragment and canal morphology. Spine. 1997;22:1650-1660.

39 Mirovsky Y, Neuwirth MG, et al. Automated percutaneous discectomy for reherniations of lumbar discs. J Spinal Disord. 1994;7:181-184.

40 Onik G, Maroon J, Shang Y. Far lateral disc herniation: treatment by automated percutaneous discectomy. Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11:865-868.

41 Onik G. Automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy. Mt Sina J Med. 1991;58:151.

42 Haaker R, Senkal M, Kielich, et al. Percutaneous lumbar discectomy in the treatment of lumbar discitis. Euro Spine J. 1997;6:98-101.

43 Gebhard JS, Brugman JL. Percutaneous discectomy for the treatment of bacterial discitis. Spine. 1994;19:855-857.

44 Fouquet B, Goudpille P, Jattiot F, et al. Discitis after lumbar disc surgery: features of aseptic and septic forms. Spine. 1992;17:356-358.

45 Krodel A, Sturz H, Siebert CH. Indications for and results of operative treatment of spondylitis and spondylodiscitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991;110:78-82.

46 Yu W, Diu C, Wing P, et al. Percutaneous suction aspiration for osteomyelitis: report of two cases. Spine. 1991;16:198-202.

47 Theron J, Huet H, Courtheoux F. Percutaneous automated cervical discectomy. Rachis. 1992;4:93-105.

48 Matsui H, Aoki M, Kanamori M. Lateral disc herniation following percutaneous lumbar discectomy. A case report. Internat Orthoped. 1997;21:169-171.

49 Hijikata S. Percutaneous nucleotomy. A new concept technique and 12 years experience. Clin Orthop. 1989;238:9-23.

50 Bernd L, Schiltenwolf M, Mau H, et al. No indications for percutaneous lumbar discectomy. Internat Orthoped. 1997;21(3):164-168.

51 Sahlstrand T, Lonntoft M. A prospective study of preoperative and postoperative sequential magnetic resonance imaging and early clinical outcome in automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12(5):368-374.

52 Chatterjee S, Foy PM, Findlay GF. Report of a controlled clinical trial comparing automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy and microdiscectomy in the treatment of contained lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 1995;20:734-738.

53 Nachemson A. Lumbar disc herniation – conclusions. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64(Suppl 251):49-50.

54 Stevenson RC, McCabe CJ, Findlay AM. An economic evaluation of a clinical trial to compare APLD with microdiscectomy in the treatment of contained lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 1995;20(6):739-742.

55 Choy DSJ, Altman PA, Case RB, et al. Interaction of laser radiation with human intervertebral discs at wavelengths of 193 nm, 488 nm, 514 nm, 1064 nm, 1318 nm, 2150 nm, 2940 nm, 10600 nm. Clin Orthop. 1990;267:245-250.

56 Choy DSJ, Altman P. Fall of intradiscal pressure with laser ablation. Spine State Art Rev. 1993;7:23-29.

57 Ohnmeiss DD, Guyer RD, Hochschuler SH. Laser disc decompression: the importance of proper patient selection. Spine. 1994;19:2054-2058. discussion 2059

58 Hellinger J, Linke R, Heller H. A biophysical explanation for Nd:YAG percutaneous laser disc decompression success. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2001;5(19):235-238.

59 Harada J, Dohi M, Fukuda K, et al. CT-guided percutaneous laser disk decompression for cervical disk hernia. Radiation Med. 2001;5(19):263-266.

60 Liebler WA. Percutaneous laser disc nucleotomy. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1995;310:58-66.

61 Gangi A, Dietemann JL, Casser B. Interventional radiology with laser in bone and joint. Rad Clin North Am. 1998;36(3):547-557.

62 Choy D. Early relief of erectile dysfunction after laser decompression of herniated lumbar disc. J Clinical Laser Med Surg. 1999;1(17):25-27.

63 Bosacco SJ, Bosacco DN, Berman AT. Functional results of percutaneous laser discectomy. Am J Orthoped. 1996;25(12):825-828.

64 Nerubay J, Casi I, Levinkopf M. Percutaneous carbon dioxide laser nucleolysis with 2–5 years follow-up. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1997;337:45-48.

65 Hellinger J. Technical aspects of the percutaneous cervical and lumbar laser disc decompression and nucleotomy. Neurol Res. 1999;21:99-102.

66 Nerubay J, Caspi I, Levinkopf M, et al. Percutaneous laser nucleolysis of the intervertebral lumbar disc: an experimental study. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1997;337:42-44.

67 Choy DSJ, Asher PW, Saddekni S, et al. Percutaneous laser decompression. Spine. 1992;17:949-956.

68 Choy DS. Percutaneous laser disc decompression: twelve years’ experience with 752 procedures in 518 patients. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1998;16(6):325-331.

69 Gropper GR, Robertson JH, McClellan G. Comparative histological and radiographic effects of CO2 laser versus standard surgical anterior discectomy in the dog. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:42-47.

70 Black J, Rhodes A, Lane GJ, et al. The chronic effects of anterior cervical and percutaneous lumbar discectomy using the holmium: YAG laser: an animal model. State of the Art Reviews (Spine). 1993;7:31-36.

71 Reinhard SWR, Kraemer J. Chemonucleolysis versus laser disc decompression: a prospective randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1997;79:247.

72 Dangaria T. Result of laser-assistant disc ablation after unsuccessful percutaneous discectomy. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 1998;16(6):321-323.

73 Chiu JC, Clifford TJ, Greenspan M, et al. Percutaneous microdecompressive endoscopic cervical discectomy with laser thermodiskoplasty. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67:278-282.

74 Knight M, Goswami A, Patko J. Cervical percutaneous laser disc decompression: preliminary results of an ongoing prospective outcome study. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2001;1(19):3-8.

75 Chen Y, Sang-heon L, Chen D. Intradiscal pressure study of percutaneous disc decompression with nucleoplasty in human cadavers. Spine. 2003;28(7):661-665.

76 Chen Y, Sang-Heon L, Saenz Y, et al. Histological findings of disc, endplate and neural elements after coblation of nucleus pulposus: an experimental nucleoplasty study. Spine. 2003;6(3):466-470.

77 Bhagia SM, Slipman CW, Nirschl M, et al. Side effects and complications after percutaneous disc decompression using coblation technology. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(1):6-13.

78 Slipman CW, Bhagia SM, Frey ME, et al. Nucleoplasty procedure for cervical radicular pain – initial case series. In: Proceedings of interventional Spinal Injection Society. Orlando, FL; 2003:104–105.

78a Slipman CW, Frey ME, Bhargava, et al. Outcomes and side effects following percutaneous cervical disc decompression using coblation technology: a pilot study. The Spine Journal. 2004;4:71S.

79 Derby R, Chen Y, Lee SH, et al. Non-surgical interventional treatment of cervical and thoracic radiculopathies. Pain Phys. 2004;7:389-394.

80 Singh Vijay, et al. Percutaneous disc decompression using coblation (Nucleoplasty™) in the treatment of chronic discogenic pain. Pain Phys. 2002;5(3):250-259.

81 Sharp L. Percutaneous disc decompression using nucleoplasty. Pain Phys. 2002;5(2):121-126.

82 Nardi PV, Cabezas D, Cesaroni A. Percutaneous cervical nucleoplasty using coblation technology. Clinical results in fifty consecutive cases. Acta Neurochiir Suppl. 2005;92:73-74.

83 Slipman CW, Bender F, Menkin S, et al. Percutaneous lumbar disc decompression using the Dekompressor: A Pilot Study. Procedings of the 67th Annual Meeting of The American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Hawaii, Nov 9–12, 2005.

84 Alo K, et al. Percutaneous lumbar discectomy: one year follow up in an initial cohort of fifty consecutive patients with chronic radicular pain. Pain Practice. 2005;5(2):116-124.

85 Amoretti N, et al. Decompression probe (Dekompressor) in percutaneous discectomy. Ten case reports. J Clin Imaging. 2005;29:98-101.

Côté P, Cassidy D, Corroll L. The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey. The prevalence of neck pain and related disability in Saskatchewan adults. Spine. 1998;23:1689-1698.

Linton SJ, Hellsing AL, Hallden K. A population-based study of spinal pain among 35–45 year old individuals. Prevalence, sick leave and health care use. Spine. 1998;23:1457-1463.

Borghouts JAJ, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Cost-of-illness in neck pain in the Netherlands in 1996. Pain. 1999;80:629-636.

Deyo RA, Bass JE. Lifestyle and low back pain. Spine. 1989;14:501.

Bigos SJ, Battie MC. The impact of spinal disorders in industry. In: Frymoyer JW, editor. The adult spine. New York: Raven Press, 1991.

Schwarzer A, Aprill C, Derby R, et al. The prevalence and clinical features of internal disc disruption in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:1878-1883.