CHAPTER 7 Peptic ulcer surgery

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

♦ A dissection of the esophagus at the hiatus will expose the anterior and posterior vagal trunks.

♦ The anterior vagus is intimately related to the anterior esophagus as it traverses from left to right. Circumferential dissection of the vagal trunk will permit placement of surgical clips as well as interval truncal resection for pathologic confirmation.

♦ The posterior vagal trunk has a more variable association to the esophagus but is most often found along the right esophagus between the 7 and 9 o’clock position.

♦ When performing an antrectomy, the gastroduodenal artery should be ligated to ensure proper mobilization of the first and second portion of the duodenum.

♦ The chronic regional inflammation may hinder dissection of the pylorus from the head of the pancreas.

♦ Inadequate mobilization could impair stapling distal to the pylorus and leave retained antrum at the staple line. Retained antrum may lead to recurrent ulcer disease and surgical failure. A full Kocher maneuver is rarely necessary to achieve adequate duodenal mobilization.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

Patient preparation

♦ The advent of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has greatly diminished the frequency and volume of peptic ulcer surgery for the practicing general surgeon. Conversely, because of the use and availability of PPIs, only the most severe cases of ulcer disease present for surgical evaluation. A cautious and thorough preoperative workup is paramount.

♦ Patient selection may be the most difficult preoperative activity for the physician. PPI medication noncompliance, chronic NSAID use, smoking, and alcohol use are the most common patient factors that aggravate the disease process. Likewise, these patient factors predict poorer clinical outcomes from surgical intervention. All patients should be counseled appropriately.

♦ The ubiquity of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has greatly impacted the frequency and volume of peptic ulcer surgery. Additionally, advancements in therapeutic endoscopic techniques, such as pneumatic balloon dilatation, have reduced the need for the classically described antiulcer surgical procedures. Though the frequency of antiulcer operations has dropped, the severity of ulcer disease that prevails often yields the need for surgical evaluation.

♦ The most common indication for vagotomy and pyloroplasty is gastric outlet obstruction caused by chronic and recurring pyloric channel ulcer disease. Most patients will have had one or multiple therapeutic endoscopic procedures, such as pneumatic balloon dilatation. Reviewing the endoscopic procedure history and photographic documentation will enhance not only correct patient selection but also correct procedural selection.

♦ The most common indication for vagotomy and antrectomy is a chronic nonhealing peptic ulcer. In addition to removing any concerning gastric pathology, antrectomy will also improve acid suppression. Depending on the indication, the antrectomy may improve acid suppression and/or remove concerning gastric pathology. Prior to surgical evaluation, patients may have had months of multidrug antiulcer therapy, repeated H. pylori eradication regimens, and numerous ulcer biopsies to rule out occult malignancy. Reviewing the endoscopic procedure history, biopsy pathology results, and procedural photographic documentation will enhance both patient selection and correct procedural selection.

Anesthesia

♦ General endotracheal intubation is recommended for this procedure. The anesthesiologist may insert an orogastric tube to decompress the stomach after induction. Your anesthesia team may prefer a rapid sequence protocol because of the aspiration risk associated with retained gastric contents. Alternatively, if endoscopy is planned as an adjunct to the laparoscopic procedure, therapeutic endoscopic suction and decompression after intubation would be advantageous.

Step 3. Operative steps

Truncal vagotomy with pyloroplasty

Access and port placement

♦ Combining the truncal vagotomy with pyloroplasty makes port site placement different from most other foregut operations. The inferior and right lateral location of the pylorus requires moving the camera and surgeon’s working ports to a more inferior position on the abdomen.

♦ The location for optimal triangulation of the pylorus can be achieved by placing the three trocars in line at the level of the umbilicus. A fourth trocar can be placed in the left subcostal location for an assistant’s instrument. A liver retractor, such as a Nathanson retractor, can be placed though a subxyphoid access site.

Truncal vagotomy

♦ The truncal vagotomy can be performed early in the operation, and often as the first step. Begin by opening the pars flaccida of the gastrohepatic ligament to facilitate identification of the right crus. Division of the phrenoesophageal ligament anterior to the esophagus will permit entry into the mediastinum. A limited dissection of the esophagus at the hiatus will expose the anterior and posterior vagal trunks.

♦ Circumferential dissection of the vagal trunks will permit placement of proximal and distal surgical clips as well as interval truncal resection for pathologic confirmation.

Pyloroplasty

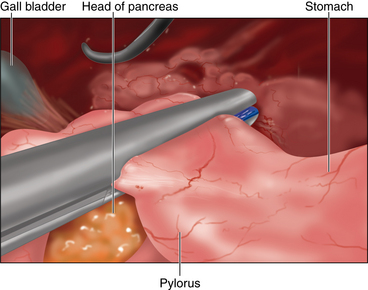

♦ When addressing the pyloroplasty, expect adhesions to the omentum and gallbladder overlying the duodenum resulting from the chronic inflammatory process.

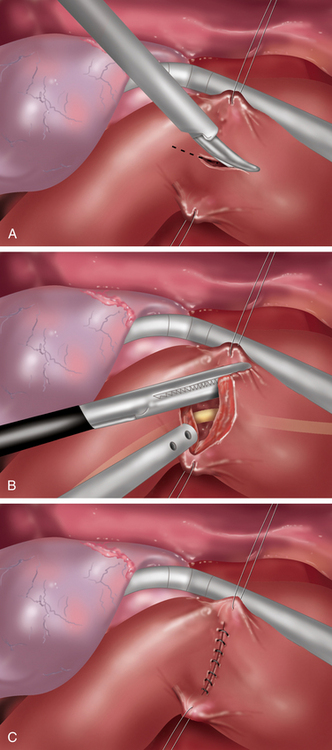

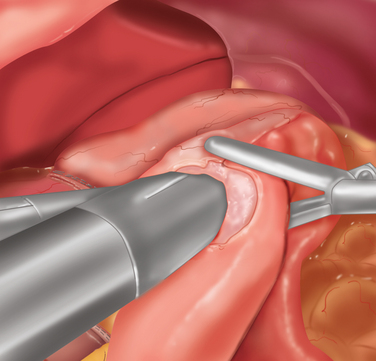

♦ Placement of a superior and inferior traction suture facilitates optimal exposure and control of the tissue. A generous transverse incision should be extending 2 to 3 cm on both sides of the pylorus. The fibrotic and often circumferential nature of this lesion makes the closure difficult. Extending the incision onto soft, pliable tissue of both the antrum and duodenum makes the laparoscopic closure easier. A 4- to 6-cm pyloroplasty should be performed. The longer pyloroplasty will create a larger cross-sectional area that will reduce the risk of postoperative stenosis (Figure 7-3a).

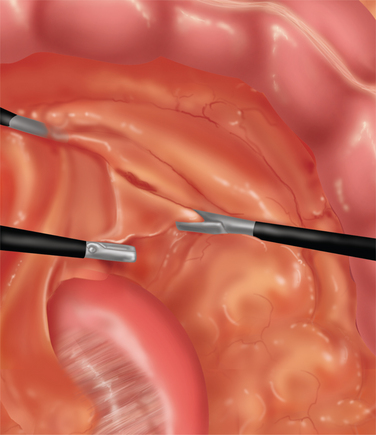

♦ It is important to open the ulcer channel between the antral and duodenal sides of the pylorus. This channel can be short or long, but it is typically very sclerotic and narrow. Endoscopic placement of a transpyloric feeding tube or guidewire greatly facilitates guidance of the enterotomy across the pyloric channel (Figure 7-3b).

♦ Laparoscopic vertical closure of the pyloroplasty is accomplished by a running single full-thickness closure, a Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty. To ensure closure of the incision’s corners, begin separate sutures at the superior and inferior corners, meeting in the center (Figure 7-3c).

♦ Once the pyloroplasty is closed, endoscopic visualization confirms both the patency of the lumen and air tightness of the sutured repair.

Laparoscopic truncal vagotomy with antrectomy with billroth II anastomosis

Access and port placement

♦ Trocar positioning for this operation is similar to most foregut operations. A camera port placed 15 cm below the xyphoid process will optimize the view of stomach, the ligament of Treitz, and the esophageal hiatus. Two ports are inserted for the surgeon on the right side of the upper abdomen. A left subcostal trocar will allow an assistant to provide proper retraction. A liver retractor, such as a Nathanson retractor, can be placed though a subxyphoid access site.

See the preceding information for details of truncal vagotomy.

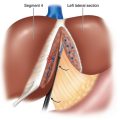

Antrectomy

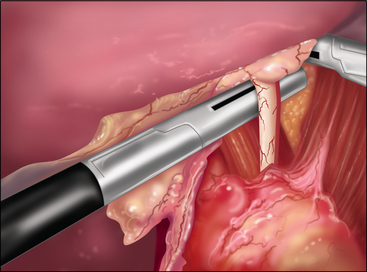

♦ Proceeding to the antrectomy, the lesser sac is entered along the greater curvature of the stomach. The dissection is carried toward the pylorus and behind the stomach to its lesser curve (Figure 7-4).

♦ The gastroduodenal artery will be ligated to ensure adequate duodenal mobilization.

♦ Next, the dissection is started along the stomach’s lesser curvature and the superior margin of the duodenum’s second portion.

♦ A full Kocher maneuver is rarely necessary to achieve adequate duodenal mobilization, although mobilization of the first and second portion of the duodenum is important. The chronic regional inflammation may hinder dissection of the pylorus from the head of the pancreas. Inadequate mobilization could impair proper stapling distal to the pylorus and thereby create a problem of retained antrum. Retained antrum may lead to recurrent ulcer disease and surgical failure.

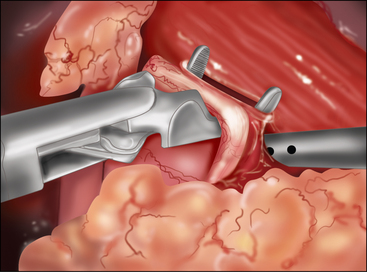

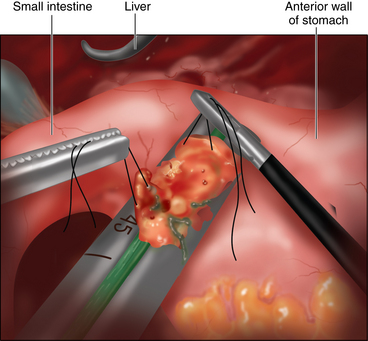

♦ Once mobile, the duodenum is divided using a linear laparoscopic stapling device (Figure 7-5).

♦ A linear transection line across the stomach is chosen to ensure removal of the antrum. Once the antrectomy is complete, the specimen is set aside for removal at the end of the procedure.

Billroth II anastomosis

♦ The gastrojejunal anastomosis begins by identifying the proximal jejunum. The ligament of Treitz is identified by elevating the greater omentum and transverse colon. Next, a window is made through the transverse mesocolon just above the ligament of Treitz (Figure 7-6).

♦ The proximal jejunum is placed through the mesocolon window and pulled through into the lesser sac. This creates a retrocolic orientation of the gastrojejunostomy.

♦ Next, a side-to-side, functional end-to-side gastrojejunostomy is created using a laparoscopic linear stapling device (Figure 7-7).

♦ The common enterotomy created with this technique is closed laparoscopically with a running single-layer sutured closure.

♦ Creation of the gastrojejunostomy can be performed in either a retrocolic or antecolic fashion. The benefit to the retrocolic position is the ability to bring the jejunum directly from the fixed position at the ligament of Treitz to the gastric staple line. This creates the shortest afferent limb, minimizing the risk of afferent limb syndrome postoperatively.

Step 4. Postoperative care

♦ The patient is kept NPO (nil per os) until a Gastrografin upper gastrointestinal swallow study is complete. This study documents patency of the intestinal lumen and competency of closure.

♦ A strict postoperative diet, beginning with clear liquids and advancing to a solid diet over a 6-week period, may allow for proper intestinal healing and mitigate patient dietary intolerances.

♦ Reinforcement of the importance of good patient lifestyle choices, mainly smoking cessation, NSAID cessation alcohol abstinence, and PPI medication compliance, will enhance patient outcomes.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ Patient selection and preoperative preparation stresses the positive impact that healthy lifestyle choices will improve long-term outcomes. The procedure emphasizes the importance of smoking cessation, alcohol abstinence, and that PPI medication compliance is paramount.

♦ The value of intraoperative endoscopy cannot be over emphasized.

At the beginning of the case, decompressing the stomach will limit the aspiration risk at the time of extubation.

At the beginning of the case, decompressing the stomach will limit the aspiration risk at the time of extubation.Step 1. Surgical anatomy

♦ In emergency surgery such as perforated peptic ulcer disease, the difficulty identifying the pertinent anatomy depends greatly on the duration and severity of the perforation.

♦ The majority of perforations presenting emergently will occur on the anterior stomach and duodenum. Entering the lesser sac along the greater curve will facilitate posterior wall inspection.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

♦ Despite the widespread use of prescription PPIs and over-the-counter H2 blocker medications, peptic ulcer disease remains one of the most common causes of acute intestinal perforation requiring emergent surgical treatment. Smoking, alcohol use, and medication non-compliance are common patient factors contributing to disease prevalence. Additionally, the rise in chronic use of over-the-counter non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) has, in particular, elevated the risk of ulcer perforation.

♦ The traditional treatment has been and remains: preoperative volume resuscitation of the patient, surgical treatment including washout and source control, and diligent postoperative care. Over the last two decades the primary method of source control has been omental patching of the perforated ulcer (Graham patch). Additionally, ulcer resection may be used for gastric ulcers on mobile portions of the stomach.

♦ The use of laparoscopic techniques in cases of acute intestinal perforation is an emerging area for application. Though several cases series in the 1990s proved the safety and efficacy of minimally invasive techniques, in 2008 less than 5% of all cases of perforated peptic ulcers were treated laparoscopically.

Step 3. Operative steps

Access and port placement

♦ Trocar positioning for this operation is similar to laparoscopic pyloroplasty procedure. A camera port placed 15 cm below the xyphoid process will optimize the view of the entire abdomen. The location for optimal triangulation of the pylorus can be achieved by placing the three trocars in line at the level of the umbilicus.

♦ A fourth trocar can be placed in the left subcostal location for an assistant’s instrument. A liver retractor, such as a Nathanson retractor, can be placed though a subxyphoid access site.

♦ Once laparoscopic access has been achieved, a careful inspection of the abdomen is performed, making special note of loculated fluid collections that will require thorough irrigation.

♦ Next, localization of the perforation site is carried out. Anterior perforations of the stomach and duodenum are most common, but locating the perforation may be or prove difficult. Intra-operative endoscopy can facilitate the search. If not directly visualized endoscopically, the insufflation of air to distend the stomach will force air through the perforation creating a bubbling effect seen laparoscopically.

♦ Once located, a thorough irrigation and inspection is done to fully evaluate the location, size, and depth of the ulcer.

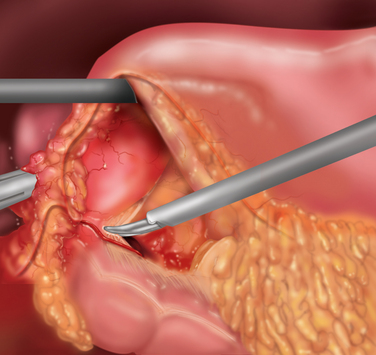

♦ In the case of an ulcer occurring on the body of the stomach, laparoscopic ulcer resection can be considered. This should be a full-thickness gastric wall resection and can be potentially done as a stapled resection. Placement of stay sutures along the ulcer edge can assist in ensuring proper laparoscopic stapler positioning (Figure 7-8).

♦ For ulcers on the lesser curve of the stomach or pylorus, resection is unlikely. A Graham patch procedure can be performed laparoscopically. A pedicle of omentum is needed for the laparoscopic Graham patch. Dividing the omentum vertically up to the transverse colon creates a long free pedicle of omentum that can reach without tension.

♦ Next, 3 to 5 sutures are placed taking seromuscular bites on both sides of the ulcer. The omental pedicle is placed over the ulcer and on top of the sutures. Sequential tying of the interrupted sutures is completed securing the Graham patch (Figure 7-8).

♦ An air leak test can be performed by endoscopically insufflating the stomach while irrigating the repair.

♦ Gastric ulcers should either be biopsied to rule out malignancy, or resected if located on a mobile portion of the stomach. The laparoscopic Graham patch may be completed after biopsy or resection similar to the manner described above.

♦ After source control is complete, thorough washout of the abdomen and pelvis should be done. By repositioning the bed from right to left and from head up to head down, copious irrigation can be accomplished, thereby removing contamination.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ The primary failure rate of the Graham patch procedure has been reported to be between 5% and 25%. This has not changed with laparoscopic techniques. An omental pedicle flap secured under tension may be one reason for Graham patch leakage. Dividing the greater omentum vertical up to the transverse colon will yield a pedicle that will reach without tension and preserve omental pedicle perfusion.

♦ A second potential factor for patch failure may be related to suture fixation techniques of the pedicle. Common leakage points are at the superior or inferior margins of the ulcer-patch repair. Placing fixation sutures above and below the ulcer margins will reduce the chance of leakage from the apical margins of the Graham patch repair.

♦ Management of 3 to 5 intracorporeal sutures at one time can be cumbersome. Using two different suture materials or colors, for instance 2-0 silk and 2-0 Vicryl, may make intracorporeal knot-tying and omental pedicle fixation less frustrating.

Arora G, Singh G, Triadafilopoulos G. Proton pump inhibitors for gastroduodenal damage related to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or aspirin: twelve important questions for clinical practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7;7:725-735.

Bertleff MJ, Halm JA, Bemelman WA, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open repair of the perforated peptic ulcer: the LAMA Trial. World J of Surg. 2009;33;7:1368-1373.

Fromm D, Resitarits D, Kozol R. An analysis of when patients eat after gastrojejunostomy. Ann Surg. 1988;207(1):14-20.

Gutiérrez de la Peña C, Márquez R, Fakih F, et al. Simple closure or vagotomy and pyloroplasty for the treatment of a perforated duodenal ulcer: comparison of results. Dig Surg. 2000;17;3:225-228.

Gibson JB, Behrman SW, Fabian TC, Britt LG. Gastric outlet obstruction resulting from peptic ulcer disease requiring surgical intervention is infrequently associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191(1):32-37.

Hermansson M, Ekedahl A, Ranstam J, Zilling T. Decreasing incidence of peptic ulcer complications after the introduction of the proton pump inhibitors, a study of the Swedish population from 1974-2002. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:25.

Hobsley M, Tovey FI, Holton J. Precise role of H pylori in duodenal ulceration. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(40):6413-6419.

Laws HL, McKernan JB. Endoscopic management of peptic ulcer disease. Ann Surg. 1993;217(5):548-555.

Matsuda M, Nishiyama M, Hanai T, et al. Laparoscopic omental patch repair for perforated peptic ulcer. Ann Surg. 1995;221(3):236-240.

Mihmanli M, Isgor A, Kabukcuoglu F, et al. The effect of H. pylori in perforation of duodenal ulcer. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45(23):1610-1612.

Rivera RE, Eagon JC, Soper NJ, et al. Experience with laparoscopic gastric resection: results and outcomes for 37 cases. Surg Endosc. 2005;19;12:1622-1626.

Sachdeva K, Zaren HA, Sigel B. A Surgical treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Med Clin North Am. 1991;75(4):999-1012.

Søreide K, Sarr MG, Søreide JA. Pyloroplasty for benign gastric outlet obstruction: indications and techniques. Scand J Surg. 2006;95;1:11-16.

Vonkeman HE, Klok RM, Postma MJ, et al. Direct medical costs of serious gastrointestinal ulcers among users of NSAIDs. Drugs Aging. 2007;24;8:681-690.

Woodward ER. The history of vagotomy. Am J Surg. 1987;153(1):9-17.