6 Pelvic pain, endometriosis and minimal-access surgery

Pelvic pain

Clinical features

• What is the nature, site, type and onset of the pain? Is it constant or intermittent? Is it colic-like?

• What are the exacerbating and relieving factors?

• How does it relate to periods? A 3-month symptom diary is helpful in relating the pain to the hormonal cycle.

• How does the pain vary with defecation or micturition? Are there associated factors such as nausea, vomiting, bloating or malaise?

• A thorough urinary and bowel history is always necessary.

• Is there any significant previous surgical history?

• Is there a history of sexually transmitted infection?

• Is there a history of fertility problems?

• Have there been previous pregnancy complications, such as ectopic, evacuation of retained products of conception or termination of pregnancy?

• Is the woman currently in a relationship? Are there any relationship or sexual problems?

• Is there a history of sexual abuse in childhood or adult life?

Investigations

Management

Acute pelvic pain

Acute pelvic inflammatory disease

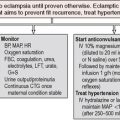

Suspected PID must be managed urgently, as described in Chapter 9. A low threshold for antibiotic treatment is important to minimize complications of tubo-ovarian abscess, chronic pain, subfertility or ectopic pregnancy.

Endometriosis

Definition

Endometriosis is the presence of functioning endometrial tissue outside the cavity of the uterus.

Aetiology

Various theories exist about the development of endometriosis:

There is also increasing evidence for a complex genetic predisposition to endometriosis.

Investigations

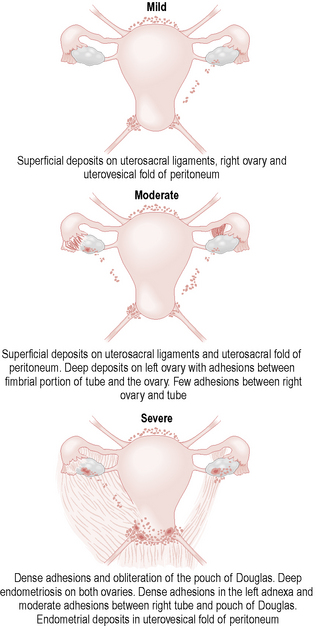

Laparoscopic appearances include:

• Blue or black powder burn lesions

• Red, blue or white papular or flat lesions

• Peritoneal scarring and fenestrations (‘peritoneal windows’)

• Frozen pelvis (fixed, immobile uterus with dense adhesions to ovaries and tubes and obliterated pouch of Douglas).

The commonest sites of endometriosis are the ovaries, uterosacral ligaments and pouch of Douglas.

Endometriosis may be classified as stage I–IV by the revised American Fertility Society Score, according to the severity and extent of the disease at laparoscopy. More commonly, the laparoscopic findings are recorded diagrammatically and a judgement of mild, moderate or severe endometriosis assigned. Figure 6.1 illustrates some typical patterns of endometriosis found at laparoscopy.

Treatment

Medical

Hormonal medical treatment

Fertility is not improved by hormonal treatments, all of which delay conception further.

Minimal-access surgery

Laparoscopy

The uses of laparoscopy in gynaecology are shown in Table 6.1.

| Diagnostic uses of laparoscopy: |

| Pelvic pain (acute or chronic) |

| Subfertility (to assess for endometriosis and to look for spill of dye during a dye test) |

| Suspected ectopic pregnancy |

| Therapeutic uses of laparoscopy: |

| Sterilization |

| Adhesiolysis |

| Diathermy/laser/excision of endometriosis |

| Salpingectomy (ectopic pregnancy, hydrosalpinx) |

| Salpingotomy (ectopic pregnancy, hydrosalpinx) |

| Ovarian cystectomy |

| Oophorectomy |

| Myomectomy |

| Colposuspension |

| Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy |

| Lymphadenectomy |

Preoperative counselling

Preoperative counselling should cover the following points:

• Indication for the procedure – Is this the appropriate operation? Has the clinical situation changed since the outpatient consultation? If there was an ovarian cyst, has a repeat scan been performed to check it has not resolved?

• Last menstrual period: all premenopausal women should have a pregnancy test on the day of the procedure. If it is negative and they have had unprotected sex, they must be warned about the potential risk of instrumentation of the uterus to a very early pregnancy.

• Proposed procedure: women need an explanation of the proposed procedure, the reasons for it and the possible findings. It should be explained that images are printed out for the medical records and to help the patient understand the findings.

• Possible findings: it should be explained that laparoscopy is often normal in women with pelvic pain.

• Complications of the procedure and how they may be dealt with (laparotomy).

Technique

The essential steps involved with the basic laparoscopy procedure are the following:

• Ensure the woman has been fully counselled about the proposed procedure, reasons and risks for the operation, with informed consent given.

• Place patient level on the operating table with the legs at 45°; clean and drape the abdomen.

• Clean the external genitalia and vagina and catheterize.

• Examine bimanually to assess for uterine position, mobility, size and any pelvic masses.

• With a Sims speculum inserted along the posterior vaginal wall, insert an instrument (ideally, a Spackman-style) through the cervix into the uterine cavity for manipulation during the procedure and then remove the speculum.

• Check the instruments (light source, Veress needle, gas supply, trocar, laparoscope, any electrocautery equipment).

• Make a small vertical or horizontal infraumbilical incision (depending on the size of the trocar and laparoscope to be used, usually 5–10 mm) with a scalpel.

• Insert the Veress needle at 45° (towards the sacral promontory) and check the position by hearing a ‘double click’ as it passes through the rectus sheath and the peritoneum, saline test and by checking the gas flow and pressure once connected.

• Insufflate with carbon dioxide until the intra-abdominal pressure reaches 18 mmHg.

• Remove the Veress needle and insert the trocar through the same incision (the anterior abdominal wall can be lifted or pressure exerted superiorly to enhance tension).

• Remove the introducer from the trocar and insert the laparoscope. Once the correct position is confirmed then attach and switch on the gas, aiming for an operating pressure of 14–18 mmHg.

• Place the patient in the Trendelenburg position (head down).

• Under direct vision, insert secondary ports, commonly in the right or left iliac fossae, lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels or in the suprapubic region. These can be used for graspers, irrigation, scissors, diathermy or drains.

Closure of the wounds

• Secondary ports should be removed under direct vision to check for bleeding from the sites and for any entrapment of bowel or fat in the port site.

• Expel as much gas as possible through the trocar.

• Close the rectus sheath where the incisions are greater than 5 mm (except at the umbilicus).

• Close skin wounds with skin glue, absorbable sutures or Steri-strips.

Postoperative management

• Intraoperative and postoperative analgesia should be given as required.

• In recovery the woman is encouraged to eat and drink as soon as she feels ready.

• When the woman has had something to eat and drink, passed urine and is not in severe pain, she can usually be discharged within 2–4 hours.

• A 5-day course of paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (or dihydrocodeine) is usually sufficient for pain management and the patient should be advised about shoulder-tip pain, from peritoneal irritation by gas.

Safety in laparoscopy

Important safety factors include the following:

• Good visualization. There may be a problem with the lens, light source or monitor. Alternatively, blood within the abdominal cavity may be absorbing light and decreasing view. The operating doctor or assistant should ensure that the area of interest and all instruments are at the centre of the view at all times.

• Alternative entry techniques. Where adhesions are suspected an open entry can be used (Hasson technique). Alternatively, Palmer’s point can be used for entry, 2 cm below the left costal margin in the mid clavicular line, after excluding splenomegaly.

Electrosurgery in laparoscopy

Electrosurgery (diathermy, electrocautery) uses electrical energy to coagulate or cut tissues.

Risks from diathermy include capacitive coupling, direct coupling and thermal injury.

Hysteroscopy

Table 6.2 shows the diagnostic and therapeutic uses of hysteroscopy.

| Diagnostic uses of hysteroscopy: |

| Investigation of postmenopausal bleeding |

| Investigation of intermenstrual bleeding |

| Suspected polyp on ultrasound |

| Suspected uterine abnormality associated with infertility or miscarriage |

| Therapeutic uses of hysteroscopy: |

| Retrieval of an intrauterine contraceptive device |

| Resection of fibroid |

| Resection of a polyp |

| Resection of the endometrium |

| Resection of a septum (metroplasty) |

| Division of intrauterine adhesions (Asherman’s syndrome) |

Preprocedure counselling

Preprocedure consultation should cover the following points:

• All premenopausal women must have a pregnancy test on the day of the procedure. If it is negative and they have had unprotected sex since the last menstrual period, they must be warned about the potential risk of instrumentation of the uterus to a very early pregnancy.

• Last menstrual period: menstruation at the time of hysteroscopy interferes with the operative view and theoretically increases the chance of retrograde flow of menstrual blood through the fallopian tubes, causing endometriosis. However, in some cases of intractable bleeding, not responsive to progestogen treatment, hysteroscopy may still be performed.

• The woman should have an explanation of the nature of the proposed procedure, the indication for it and the possible or expected findings.

• Explain that images will be printed or stored for the medical records and for the woman to see.

• Advise that the procedure takes only a few minutes, but that she may expect pain or discomfort during an outpatient hysteroscopy, similar to period pain, from dilatation of the cervical canal and spill of fluid into the peritoneal cavity through the fallopian tubes.

• Inform the woman of the rare complications of hysteroscopy.

• Explain that the woman should expect bleeding for up to 1 week after the procedure and may pass debris after a resection procedure.

• Simple analgesia may need to be taken for up to 24 hours.

• Explain that antibiotic prophylaxis is needed for women under 40 years.

Technique

The essential steps in the basic hysteroscopy procedure are:

• Place the patient in the Lloyd Davis position (and clean the vagina in an anaesthetized patient). Catheterization is not indicated.

• Insert a Cusco’s speculum (and gently clean the vagina in a conscious patient).

• If indicated, inject the cervix with local anaesthetic with adrenaline (epinephrine) at the 12, 3, 6 and 9 o’clock positions.

• Grasp the anterior lip of the cervix using a vulsellum forceps or tenaculum.

• Depending on the diameter of the hysteroscope, dilate the cervix.

• Insert the hysteroscope with the gas or saline flowing and guide it along the cervical canal under direct vision.

• Inspect the uterine cavity, rotating the lens to visualize the tubal ostia (cornu) and anterior and posterior walls. Observe for polyps, submucous fibroids, adhesions or irregular lesions suggestive of malignancy.

• Visualize the cervical canal carefully as the hysteroscope is removed from the uterus.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

A suggested prophylaxis regime is azithromycin (1 gram), given orally as a single dose.

Summary

• Pelvic pain is a common symptom, with both gynaecological and non-gynaecological causes. Genitourinary, gastrointestinal and gynaecological features are all important in the history.

• Pregnancy (and ectopic) must be excluded in all women with acute pelvic pain.

• Laparoscopy is the main diagnostic tool for women with pelvic pain.

• Endometriosis is a major cause of pelvic pain and infertility.

• The severity of symptoms of endometriosis correlates poorly with the extent of disease found at laparoscopy.

• All medical treatments for endometriosis have similar efficacy.

• Surgical treatment for endometriosis is more effective than medical treatment, especially in women wishing to become pregnant.

• All women undergoing hysteroscopy or laparoscopy should have a pregnancy test on the day of the procedure.