Chapter 21 Pelvic Pain

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea

PRIMARY DYSMENORRHEA

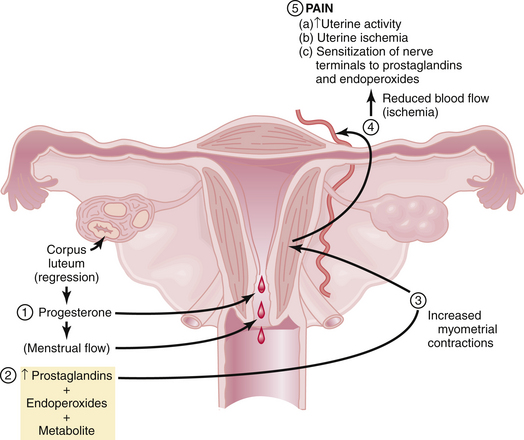

Pathophysiology

Figure 21-1 summarizes the relationships among endometrial cell wall breakdown, prostaglandin synthesis, uterine contractions, ischemia, and pain.

Clinical Features

The clinical features of primary dysmenorrhea are summarized in Box 21-1. Cramping usually begins a few hours before the onset of bleeding and may persist for hours or days. It is localized to the lower abdomen and may radiate to the thighs and lower back. The pain may be associated with altered bowel habits, nausea, fatigue, dizziness, and headache.

Treatment

Box 21-2 lists the treatment options for primary dysmenorrhea. NSAIDs, which act as COX inhibitors, are highly effective in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Typical examples include ibuprofen (400 mg every 6 hours), naproxen sodium (250 mg every 6 hours), and mefenamic acid (500 mg every 8 hours). Decreasing prostaglandin production by enzyme inhibition is the basis of all NSAIDs. Hormonal contraceptives such as oral contraceptive pills (OCs), patches, or transvaginal rings reduce menstrual flow and inhibit ovulation and are also effective therapy for primary dysmenorrhea. Extended cycle use of OCs or the use of long-acting injectable or implantable hormonal contraceptives or progestin-containing intrauterine devices minimizes the number of withdrawal bleeding episodes that users have. Some patients may benefit from using both hormonal contraception and NSAIDs.

SECONDARY DYSMENORRHEA

Clinical Features

The clinical features of some of the underlying causes of secondary dysmenorrhea are summarized in Box 21-3. In general, secondary dysmenorrhea is not limited to the menses and can occur before as well as after the menses. In addition, secondary dysmenorrhea is less related to the first day of flow, develops in older women (in their 30s or 40s), and is usually associated with other symptoms such as dyspareunia, infertility, or abnormal uterine bleeding.

Acute Pelvic Pain

Acute Pelvic Pain

Acute pain is sudden in onset and is usually associated with significant neuroautonomic reflexes such as nausea and vomiting, diaphoresis, and apprehension. It is important for the gynecologist to be aware of both the gynecologic and nongynecologic causes of acute pelvic pain (Box 21-4). Delay of diagnosis and treatment of acute pelvic pain increase the morbidity and even mortality.

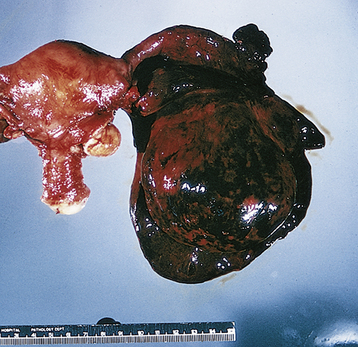

Adnexal accidents, including torsion or rupture of an ovarian (Figure 21-2) or fallopian tube cyst, can cause severe lower abdominal pain. Normal ovaries and fallopian tubes rarely undergo torsion, but cystic or inflammatory enlargement predisposes to these adnexal accidents. The pain of adnexal torsion can be intermittent or constant, is often associated with nausea, and has been described as reverse renal colic because it originates in the pelvis and radiates to the loin. An enlarging pelvic mass is found on examination and ultrasound with decreased or absent blood flow to the adnexa on Doppler ultrasound studies. The need for surgical intervention is common and urgent.

FIGURE 21-2 Torsion of an ovarian cyst.

(From Clement PB, Young RH: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgical Pathology. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2000.)

Acute reproductive organ infections such as endometritis or salpingo-oophoritis (commonly referred to as pelvic inflammatory disease [PID]) can present acutely. Rupture of a tubo-ovarian abscess is a surgical emergency that can progress to hypotension and oliguria after initially presenting with diffuse lower abdominal pain. Pelvic infection is covered in greater detail in Chapter 22.

Several complications of early pregnancy, such as ectopic gestation (see Chapter 24) and threatened or incomplete abortion can cause acute pelvic pain and are generally associated with abnormal bleeding. Ectopic tubal pregnancies produce pain as the fallopian tube dilates and ruptures into the abdominal cavity and can be life-threatening when not diagnosed expeditiously.

Nongynecologic causes of acute lower abdominal pain (see Box 21-4) are frequently seen in the differential diagnosis when a woman presents with pelvic pain. Appendicitis is a common gastrointestinal cause of acute lower abdominal pain that eventually localizes to the right lower quadrant of the abdomen (McBurney’s point). The unilateral intensity of the pain usually differentiates it from salpingo-oophoritis. Rupture of an infected appendix into the pelvic cavity can have a significant adverse effect on female fertility. Diverticular abscess is also not uncommon but usually occurs in postmenopausal women.

Acute cystitis and ureteral stone formation (lithiasis) and passage are both frequently painful. Urethral syndrome can present acutely and become chronic over time when not recognized and treated. Urinary tract disorders are covered in more detail in Chapter 23.

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy and Physiology

The pain fibers to pelvic organs are shown in Table 21-1. Painful impulses that originate in the skin, muscles, bones, joints, and parietal peritoneum travel in somatic nerve fibers, whereas those originating in the internal organs travel in visceral nerves.

TABLE 21-1 NERVES CARRYING PAINFUL IMPULSES FROM THE PELVIC ORGANS

| Organ | Spinal Segments | Nerves |

|---|---|---|

| Perineum, vulva, lower vagina | S2-4 | Pudendal, inguinal, genitofemoral, posterofemoral cutaneous |

| Upper vagina, cervix, lower uterine segment, posterior urethra, bladder trigone, uterosacral and cardinal ligaments, rectosigmoid, lower ureters | S2-4 | Pelvic parasympathetics |

| Uterine fundus, proximal fallopian tubes, broad ligament, upper bladder, cecum, appendix, terminal large bowel | T11-12, L1 | Sympathetics through hypogastric plexus |

| Outer two thirds of fallopian tubes, upper ureter | T9-10 | Sympathetics through aortic and superior mesenteric plexus |

| Ovaries | T9-10 | Sympathetics through renal and aortic plexus and celiac and mesenteric ganglia |

| Abdominal wall |

Patient Evaluation

Patient Evaluation

HISTORY

A pain history should be obtained during the first visit. Characteristics of the pain, including its location, radiation, severity, and alleviating and aggravating factors as well as effects on menstruation, level of stress, work, exercise, and intercourse should be determined. Symptoms related to the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and musculoskeletal and neurologic systems should be elicited. This process can be guided by the Pain History Mnemonic outlined in Box 21-5.

BOX 21-5 Pain History Mnemonic (OLD CAARTS)

From Rapkin AJ, Howe CN: Chronic pelvic pain: A review. In Family Practice Recertification. Monroe Township, NJ, Medical World Communications, 2006, pp 59-67.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

ORGANIC CAUSES OF CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

Of women with CPP who are subjected to diagnostic laparoscopy, about one third have no apparent pathology, one third have endometriosis, one fourth have adhesions or stigmata of chronic PID, and the remainder have other causes (Box 21-6).

UTERINE PAIN

Management

Management

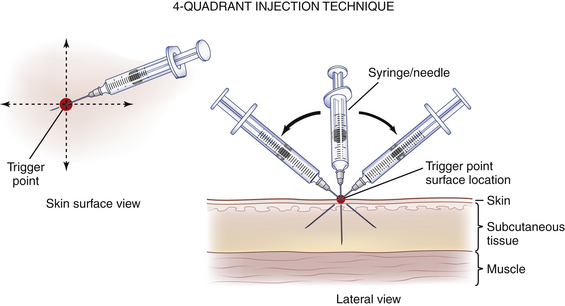

ANESTHESIA

Acupuncture, nerve blocks, and trigger-point injections of local anesthetics may provide prolonged pain relief. Acupuncture has been used successfully for dysmenorrhea, and trigger-point injections and nerve blocks with local anesthetics have been used successfully for pelvic pain. Acupuncture probably increases spinal cord endorphins. In patients who complain of pelvic pain, trigger points are usually found on either the lower abdominal wall, lower back, or vaginal and vulvar areas. A significant percentage of patients with pelvic pain have abdominal wall trigger points or nerve entrapments that respond to biweekly injections of a local anesthetic (usually up to five injections is sufficient). Anesthesia of trigger points (Figure 21-3) may abolish pain by lowering the impulses from the area of referred pain, thereby diminishing the afferent impulses reaching the dorsal horn to a level below the threshold for pain transmission. Local anesthetic nerve blocks on a repeated basis for areas of nerve impingement combined with instructions to patients about alteration in physical activity can be helpful. When needed, a prescription for nerve threshold–altering medications, as mentioned previously, can be given. These interventions can downregulate neural hypersensitivity and permanently decrease or eliminate pain.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 51. Chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:589-605.

Gambone J.C., Mittman B.S., Munro M.G., et al. Consensus statement for the management of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: Proceedings of an expert panel consensus process. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:961-972.

Peng P.W., Tumber P.S. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures for patients with chronic pelvic pain: A description of techniques and review of the literature. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2):215-224.

Rapkin A.J., Howe C.N. Chronic pelvic pain: A review. Parts 1 and 2. In: Family Practice Recertification. Monroe Township, NJ: Ascend Media; 2006:49-56. 59–67

Tu F.F., Holt J., Gonzales J., Fitzgerald C.M. Physical therapy evaluation of patients with chronic pelvic pain: A controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:272-277.

Chronic Pelvic Pain

Chronic Pelvic Pain