CHAPTER 70 PELVIC FRACTURES

Pelvic fractures are a common injury among all trauma injuries (3%). They represent a spectrum of injuries from low-energy minimally displaced fractures in the elderly population to highly displaced fractures with major injury. While most low-energy fractures can be treated conservatively, higher-energy injuries are associated with significant multisystem morbidity. In Level I trauma centers, high-energy pelvic ring injuries are often seen in conjunction with severe head injury, chest and abdominal hemorrhage, genitourinary trauma, and severe peripheral neurologic injury (6%). This chapter will address diagnosis, early management and outcomes of pelvic ring injury. Prompt recognition of a displaced pelvic fractures aids trauma surgeons in the prediction and management of hemodynamic instability.

ANATOMY

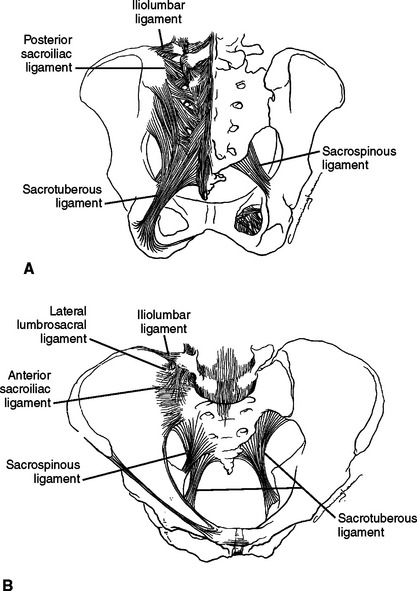

The pelvic ring is comprised of three bones: the sacrum and the two innominate bones. There is no intrinsic bony stability to the ring itself. Integrity is maintained by a series of strong ligamentous complexes and the soft tissue envelope (Figure 1). Anatomic alignment is maintained primarily by a series of posterior ligaments. The strongest of these, the interosseous ligaments, connect the tuberosities of the ilium and sacrum. The posterior sacroiliac ligaments connect the superior and inferior posterior spines of the ilium to the lateral aspect of sacrum. Similarly, the anterior sacroiliac ligaments run from the anterior surface of the sacrum obliquely to the anterior surface of the ilium. The connecting ligaments are the sacrotuberous, which runs from the dorsum of the sacrum and posterior iliac spines to the ischial tuberosity; the sacrospinous, which courses from the lateral sacrum to the ischial spine; and the iliolumbar ligaments, which run from the transverse process of L5 to the iliac crest. This group of ligaments maintains the relationship between the sacrum and the sciatic buttress, which is the body’s primary weight bearing axis. Under anatomic conditions, there is only microscopic motion at the sacroiliac joint.

Figure 1 The bony pelvis and its major posterior ligaments. (A) Posterior view. (B) Anterior view.

(From Tile M, editor: Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum, 3rd ed. Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins, 2003.)

The paired innominate bones meet anteriorly at the pubic symphysis, which is comprised of a hyaline cartilage interface reinforced by overlying fibrocartilage. The ligaments of pubic symphysis blend with the fibrocartilage to support the articulation superiorly and inferiorly. The anterior ring does not play an integral role in weight bearing but instead acts like a strut to maintain the posterior tension band.1

RADIOLOGY

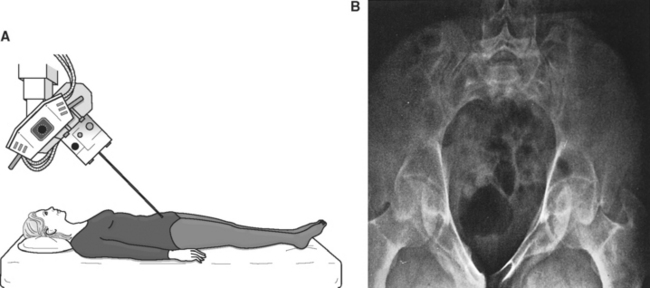

A single anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the pelvis provides valuable information about the unstable pelvic ring injuries. The anterior injury is readily apparent, and displaced/unstable posterior injuries should be apparent. Once the diagnosis of pelvic ring injury has been made, further imaging should include inlet and outlet views of the pelvis. These are obtained with the patient supine. The x-ray beam is then tilted approximately 45 degrees cephalad for the inlet view. This view elucidates displacement in the AP plane as well as rotation. The outlet view is obtained with the x-ray beam tilted 45 degrees caudad, and provides information regarding vertical displacement. Laboratory studies have demonstrated that static plain radiographs underestimate the injury displacement by 80%. CT scans provide additional valuable information regarding soft tissue injury and foraminal encroachment (Figures 2 and 3).2

CLASSIFICATION

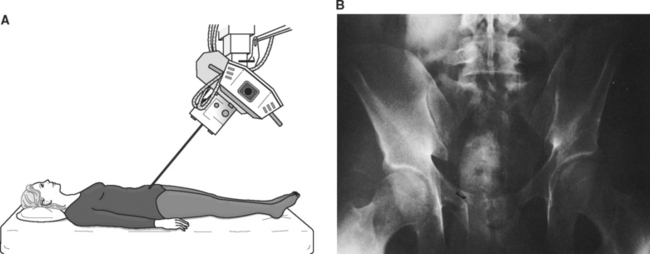

Multiple classification systems have been described in an attempt to clarify mechanisms of injury, as well as predict treatment algorithms and outcomes. The Young and Burgess classification system is based on previous systems that divided pelvic injuries by the force vector (Figure 4). Injuries are grouped into lateral compression (LC), AP compression (APC), vertical shear (VS), and combined mechanical (CM) injuries. The Young system further subdivides LC and APC injuries by degree of force with increasing grade of injury correlating with an extension of the original vector to greater forces. For example, an APC-I injury describes symphyseal widening without widening of the sacroiliac joints, while an APC-III injury involves a complete hemipelvis disruption with complete injury to the symphysis as well as disruption of both the anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligaments (Table 1).3

| Category | Primary Classifier | Secondary Classifier |

|---|---|---|

| LC-1 | Anterior ring fracture | Ipsilateral sacral compression |

| LC-2 | Anterior ring fracture | Crescent fracture |

| LC-3 | Anterior ring fracture | Contralateral APC |

| APC-1 | Symphysis diastasis | Intact anterior and posterior ligaments |

| APC-2 | Symphysis diastasis or anterior ring fracture | Disrupted anterior and posterior ligaments |

| APC-3 | Symphysis diastasis or anterior ring fracture | Disrupted anterior and posterior ligaments |

| VS | Symphysis diastasis or anterior ring fracture | Vertical displacement of posterior ring through sacroiliac joint, ilium, or sacrum |

| CM | Combination of previous patterns | Most common LC/VS or LC/APC |

APC, Anteroposterior compression; CM, combined mechanical; LC, lateral compression; VS, vertical shear.

Adapted from Burgess AR, Eastridge BJ, Young JW, et al: Pelvic ring disruptions: effective classification system and treatment protocols. J Trauma 30(7):848–856, 1990.

This classification system has two major strengths. First, there is a reproducible association among the fracture classification, associated injuries, and mortality. Acute management and evaluation of the unstable patient may be guided by injury pattern. In addition, identification of the nature of the anterior ring lesion guides diagnosis of subtle posterior injuries often missed on screening imaging studies.4

ACUTE PATIENT MANAGEMENT

A complete neurologic examination of the lower extremities with documentation of sensation and muscle grading is another critical component of the evaluation. Neurologic injuries increase in frequency and severity with increasing instability of the pelvic fracture. The nature of the nerve injury may help dictate the appropriate surgical intervention, as well as provide useful prognostic information.

MODALITIES FOR INITIAL TREATMENT

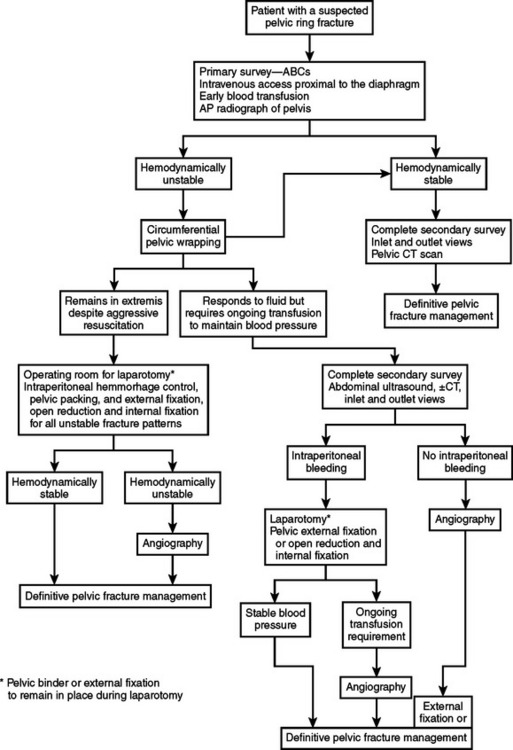

Early interventions for management of pelvic hemorrhage have been the subject of extensive debate and study. Options include angiography/embolization, laparotomy with pelvic packing, and stabilization of pelvic fractures. The keys to early management are prompt recognition of the pelvis as the source of hemorrhage and rapid implementation of an institution specific protocol for systematic stepwise intervention (Figure 5). Each intervention may have a role depending on the nature of the injury and the availability of qualified personnel.5

Figure 5 Acute management algorithm for unstable pelvic fractures.

(From Baumgaertner MR, Tornetta P, editors: Orthopaedic Knowledge Update: Trauma 3. Rosemont, IL, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2005, pp. 236–238, with permission.)

C-Clamp

The pelvic c-clamp was designed with stabilization of the posterior injury as the primary goal. Two pins are applied to the posterior ilium and connected to a large C-shaped clamp anteriorly. It can be quickly applied in the resuscitation bay without interfering with definitive pelvic fixation. The dangers of poorly placed pins in the posterior pelvis due to distorted landmarks include pin perforation into the pelvis and further displacement of the fracture. Early experience with significant complications has limited the use of this technology in the United States.6

TREATMENT AND OUTCOMES

Definitive reconstruction of unstable pelvic ring injuries is pursued once the acute inflammatory and resuscitation period has concluded. Stabilization of the ring allows early patient mobilization, improved pulmonary toilet, and decreased long-term morbidity. Many posterior ring injuries may be stabilized with percutaneous screw fixation following open or closed reduction. This avoids prominent hardware and decreases the risk of infection and soft tissue complication. The anterior injury pattern will dictate the need for and the type of operative stabilization. Anatomic restoration of the posterior ring injury is most critical for avoiding sitting imbalance and leg length discrepancy. In modern series, the majority of patients with anatomic fracture reductions maintained to union are able to return to their preinjury occupation, perform all activities of daily living, and walk without assistive devices. The minority of patients with good reductions who have suboptimal outcomes have one of several complications related to their initial injury complex.

Genitourinary complications are a common complaint amongst patients with unstable pelvic fractures. Injuries to the urethra and perineum result in long-term complications such as stricture, incontinence, and erectile dysfunction. Female patients commonly develop incontinence and dyspareuenia. There is also an increased rate of cesarean section in female patients following pelvic injury.

Studies of overall outcomes in patients with pelvic fractures have documented small but significant impacts on mental and physical well-being over the long term. Although the vast majority of patients are able to return to work and ambulation, the residual effects of these devastating injuries continue to impact day-to-day life.7

1 Tile M, editor. Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum, 3rd ed., Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 2003.

2 Kellam IF, Browner BD. Fractures of the pelvic ring. In: Browner BD, et al, editors. Skeletal Trauma. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992:849-897.

3 O’Brien PJ, Dickson KF. Pelvic fractures: evaluation and acute management. In: Baumgaertner MR, editor. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update: Trauma 3. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2005:233-242.

4 Eastridge BJ, et al. The importance of fracture pattern in guiding therapeutic decision-making in patients with hemorrhagic shock and pelvic ring disruptions. J Trauma. 2002;53:446-451.

5 Biffi WL, et al. Evolution of a multidisciplinary pathway for the management of unstable patients with pelvic fractures. Ann Surg. 2001;233:843-850.

6 Ertel W, et al. Control of severe hemorrhage using c-clamp and pelvic packing in multiply injured patients with pelvic ring disruption. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:468-474.

7 Routt ML, Copeland C. Pelvic fractures: definitive treatment and expected outcomes. In: Baumgaertner MR, editor. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update: Trauma 3. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2005:243-258.