Pelvic Anatomy From the Laparoscopic View

The anatomic view of the pelvis through a laparoscope can be somewhat disorienting to the pelvic surgeon. However, the same basic principle of understanding the relationship between important structures can be a guide. This chapter is an overview of some of the most commonly seen anatomic structures that should be visualized during most pelvic laparoscopic procedures.

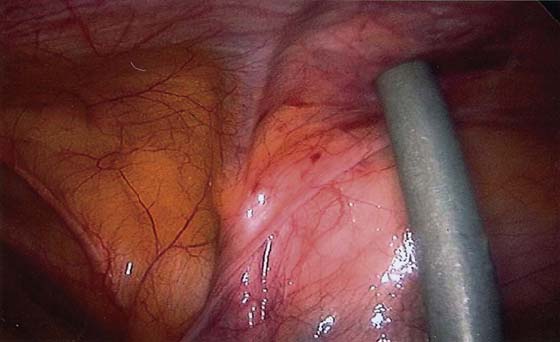

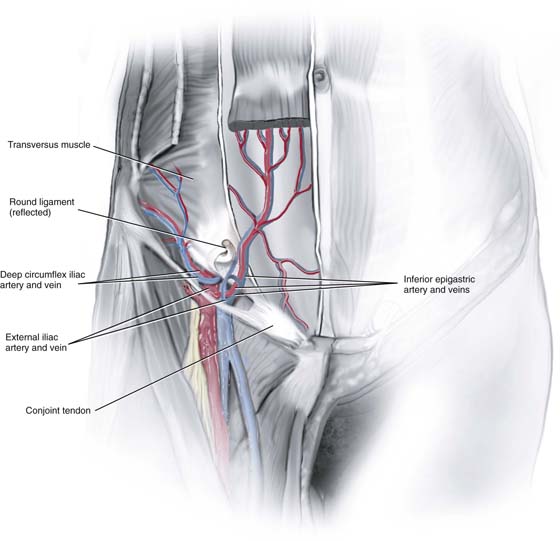

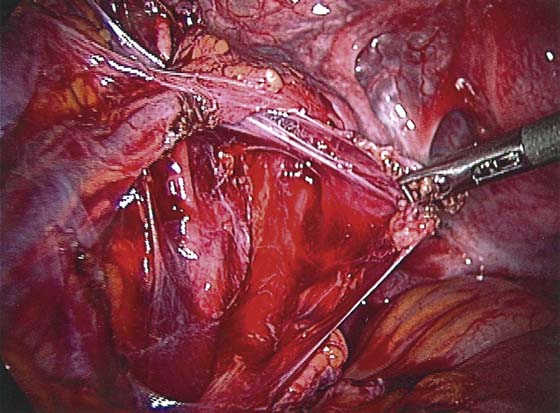

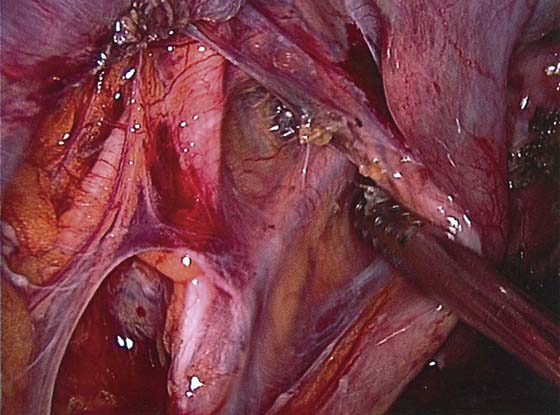

An understanding of the anterior abdominal wall anatomy is critical for proper placement of the trocars required for laparoscopy. The anatomy of the inferior epigastric vessels and their relationship to the placement of accessory ports are covered in the chapter on trocar placement. The external iliac artery has two branches: the inferior epigastric artery and the deep circumflex iliac artery. The inferior epigastric artery branches from the external iliac artery at the level of the inguinal ligament. It is seen medial to the insertion of the round ligament at the deep inguinal ring and then courses medially anterior to the peritoneum toward the rectus muscle. It can easily be seen because of the lack of fascia at this level (Fig. 113–1). It forms a fold of peritoneum called the lateral umbilical fold. Two veins usually accompany the inferior epigastric artery (Fig. 113–2). It then ascends behind the muscle and anterior to the posterior rectus sheath to anastomose with the superior epigastric vessel.

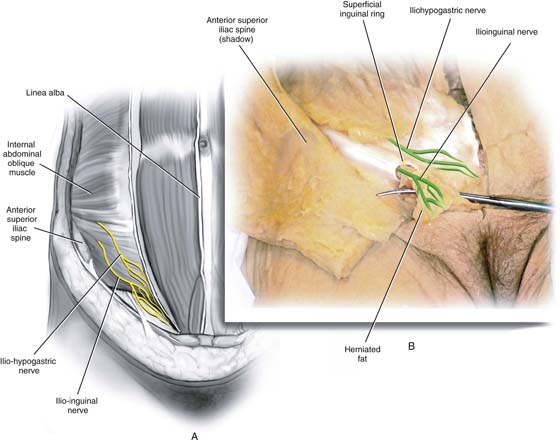

Two important nerves can be injured by the introduction of the trocar or closure of the port sites: the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves (Fig. 113–3). The iliohypogastric nerve originates from L1 and traverses through the abdominal muscles; its anterior cutaneous branch pierces the internal oblique muscle 2 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). It then travels between the internal and external oblique aponeurosis until it pierces the latter aponeurosis about 3 cm above the superficial inguinal ring. The ilioinguinal nerve also originates from L1 and traverses the internal oblique aponeurosis approximately 2 cm medial to the level of the ASIS. It travels between the external oblique and internal oblique aponeurosis and enters the inguinal canal to emerge from the superficial inguinal ring. These nerves are sensory to the ipsilateral mons pubis and labia majora; injury to them can cause paresthesia. Entrapment can cause pain over the nerve distribution. Insertion of accessory trocars above the ASIS usually avoids this injury.

FIGURE 113–1 The trocar is lateral to the right inferior epigastric vessels seen within the peritoneal fold.

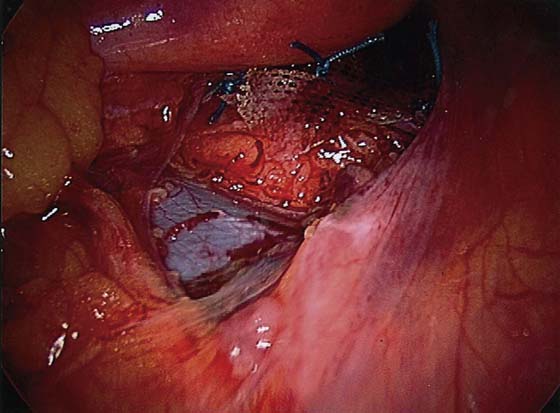

FIGURE 113–2 The right round ligament has been transected, and the inferior epigastric vessels (one artery and two veins) are seen medial to it.

FIGURE 113–3 A. The external oblique aponeurosis has been removed, and the two nerves are seen on the internal oblique muscle arising 2 cm medial to the right anterior superior iliac spine. B. The terminal branches of the two nerves are seen. The ilioinguinal nerve exits the superficial inguinal ring.

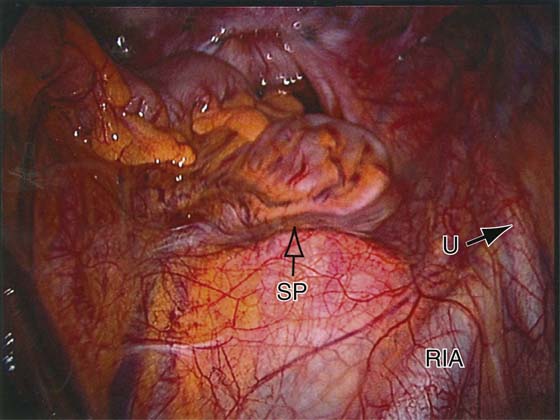

The aortic bifurcation occurs approximately at the level of L4. In nonobese patients, this is found at the level of the umbilicus. With increasing weight, the umbilicus is located more caudad to the bifurcation. Typically, a trocar or pneumoperitoneum needle is angled at 45° to avoid the aorta. However, the major vessel that is seen below the bifurcation of the aorta is the left common iliac vein, which can be injured when the primary umbilical instrument is introduced (Figs. 113–4 and 113–5). This vessel is actually the most inferior large vessel in the midline and lies approximately at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra. This area also contains the presacral nerve. The presacral nerve or superior hypogastric plexus is actually a plexus of nerves rather than a single nerve (Fig. 113–6). It lies anterior to the aortic bifurcation and left common iliac vein and therefore more prelumbar than sacral. It is retroperitoneal but can easily be stripped off the overlying peritoneum. It contains mostly sympathetic nerve fibers.

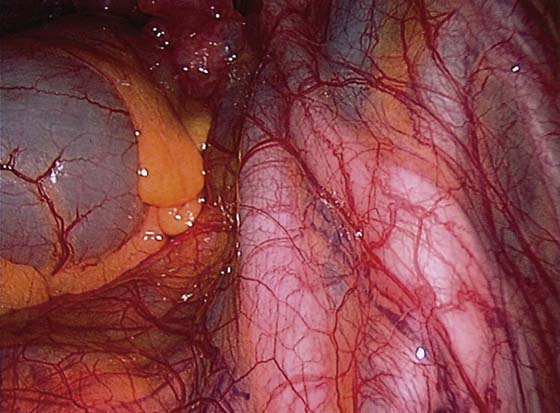

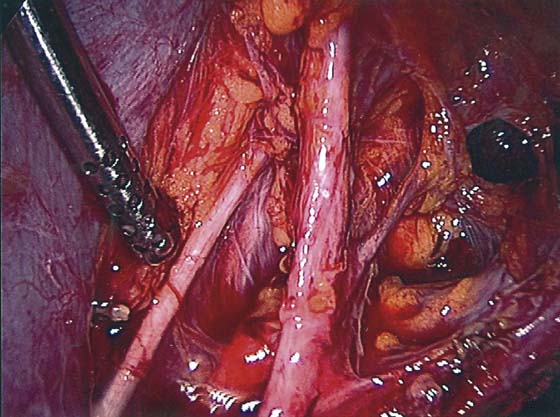

Knowledge of pelvic sidewall anatomy is critical for safe gynecologic surgery. Excision for treatment of endometriosis or hysterectomy usually involves some dissection around the ureter. Adnexal masses are occasionally adherent to the pelvic sidewall and also require dissection of the ureter. The anatomy of the ureter is often viewed in relationship to the pelvic sidewall vessels. The first view of the ureter is a panoramic one from the laparoscope (see Fig. 113–4). This view easily identifies the right ureter over the pelvic brim. The ureter is a retroperitoneal structure that descends medial to the psoas muscle. It is loosely attached to the peritoneum but will be drawn into any peritoneum that is tented upward. It enters the pelvis anterior to (crosses over) the external iliac artery or occasionally the common iliac artery (Fig. 113–7). At this level, the ovarian vessels lie in close proximity to the ureter and cross it as the vessels descend toward the ovary (Fig. 113–8). Injury to the ureter can occur at this level when the ovarian vessels are cauterized during adnexal surgery. After it enters the pelvis, it lies anterior to the internal iliac artery. On the left, clear visualization of the ureter at the pelvic brim is obscured by the sigmoid colon or its mesentery.

FIGURE 113–4 Panoramic view of the pelvis and sacral promontory. The right common iliac vessel is seen with the right ureter crossing it. The inferior mesenteric vessels (open arrow) are seen on the left. Between these two structures is the left common iliac vein.

FIGURE 113–5 The peritoneum has been removed from the presacral space in Figure 113–4, and the left common iliac is easily seen. It lies superior to the mesh that has been sutured into the sacral promontory.

FIGURE 113–6 The presacral nerve has been dissected and is grasped by an instrument. The right common iliac artery is seen.

FIGURE 113–7 The right ureter is seen crossing the right external iliac artery to lie anterior to the right internal iliac artery as it enters the pelvis.

FIGURE 113–8 The right ovarian vessels are seen close to the ureter as it crosses the pelvic brim.

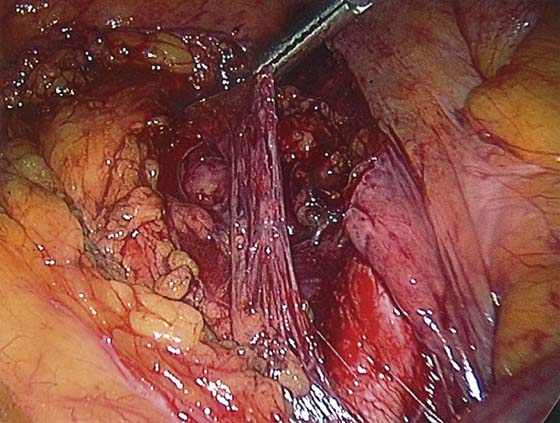

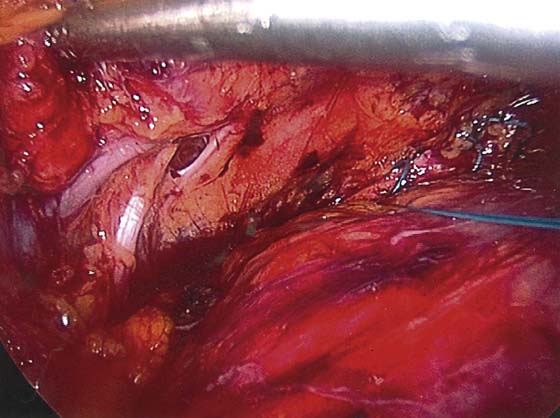

The ureter descends from the pelvic brim in loose areolar extraperitoneal tissue. It lies anterior to the internal iliac and the anterior division of this vessel. Laterally, it lies on the fascia of the obturator internus muscle. The ureter can easily be identified after an incision is made in the peritoneum under the ovarian vessels in the midpelvis. It commonly stays attached to the medial leaf of the broad ligament (peritoneum) (Fig. 113–9). It lies medial to the branches of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery, notably the uterine, inferior vesical, and umbilical arteries (Figs. 113–9 and 113–10). The uterine artery lies lateral to the ureter until it crosses it to reach the uterus (Fig. 113–11).

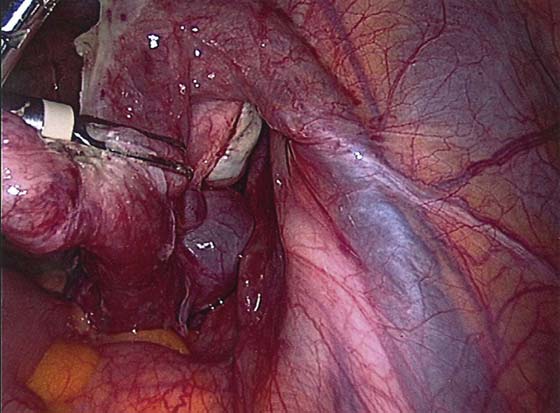

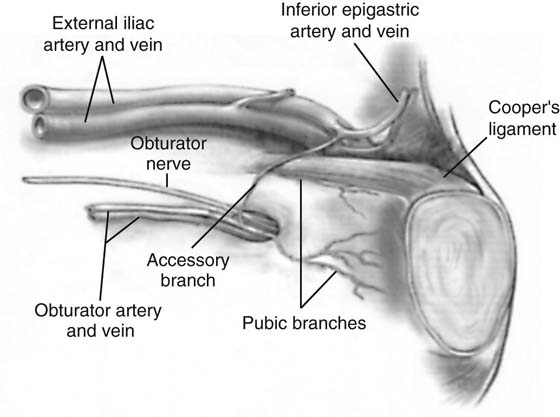

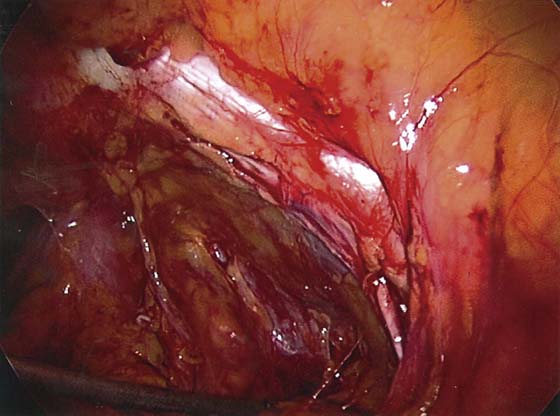

The anatomy of the pelvic wall is encountered in procedures performed for vaginal prolapse and urinary incontinence. The main structures that are visualized are represented in Fig. 113–12. These include the obturator vessels and nerve and Cooper’s ligament. The relationship of the obturator nerve and vessels to the branches of the internal iliac artery can be visualized from an intraperitoneal approach during dissection of the pelvic wall to obtain pelvic nodes (Fig. 113–13). The obturator nerve originates at L2-4 and descends in the psoas major muscle to the pelvic brim, whereupon it emerges medially to lie lateral to the internal iliac artery and its branches (see Fig. 113–13). It descends on the obturator muscle to enter the obturator foramen and exit in the thigh. It is sensory to the medial side of the thigh and motor to most of the adductor muscles.

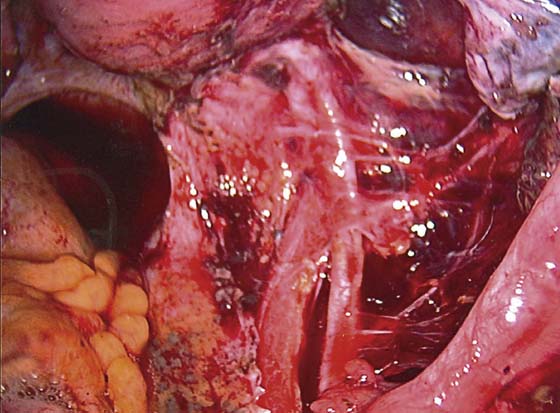

The obturator nerve and vessels in the anterior pelvis are often seen during dissection of the bladder and vagina for pelvic support or urinary incontinence surgery (Figs. 113–14 and 113–15). The obturator vessels are branches of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery. However, many variable accessory branches stem from the inferior epigastric vessels (see Fig. 113–12). The obturator vessels lie on the obturator internus muscle and enter the foramen. During a Burch procedure, a suture is placed from the perivaginal tissue into Cooper’s (pectineal) ligament. The accessory branches often lie on this ligament and can be injured easily. Cooper’s ligament is a strong fibrous band attached to the pectineal line of the pubic bone (see Fig. 113–15). In the fat lateral to this ligament lie the external iliac vessels, which can be injured if a needle entering Cooper’s ligament accidentally exists too laterally.

FIGURE 113–9 The left broad ligament (peritoneum) is pulled by the instrument, and the left ureter is seen attached to it. Lateral to the ureter is the anterior division of the internal iliac artery with the umbilical artery branching off toward the anterior abdominal wall.

FIGURE 113–10 The left ureter is retracted by the instrument, and the anterior division of the internal iliac and its two main branches (umbilical and uterine arteries) are seen. The left obturator nerve is seen lateral to the umbilical artery.

FIGURE 113–11 The peritoneum has been removed; the right uterine artery is seen lateral to the ureter and then crosses over toward the uterus.

FIGURE 113–12 This figure shows the important anatomy of the area where incontinence surgery is performed.

FIGURE 113–13 The instrument that is pointing to the obturator nerve retracts the left external iliac vein. The umbilical artery is lateral to the nerve.

FIGURE 113–14 The left obturator bundle is seen entering the obturator canal. A stitch has been placed into the paravaginal space.

FIGURE 113–15 Right Cooper’s ligament is seen as a thick band of tissue. The fat lateral to this tissue includes the external iliac vessels. The nerve is seen inferior to Cooper’s ligament.

Mark D. Walters

Mark D. Walters