Chapter 71 Pediatric Pain Management

Definition and Categories of Pain

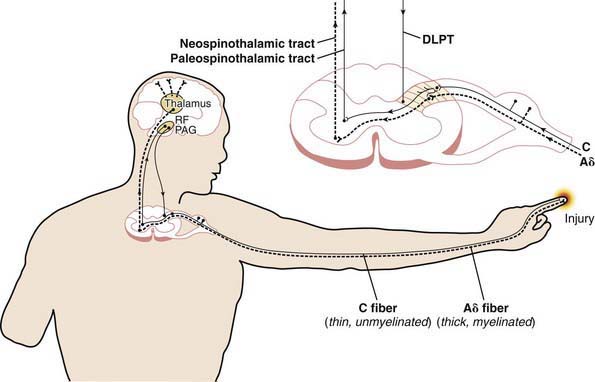

Table 71-1 specifies important pain categories commonly treated (somatic, visceral, and neuropathic) and defines the elements and characteristics of nociception, the peripheral physiologic aspect of pain perception (Fig. 71-1). Nociception refers to how specialized fibers (largely but not exclusively the A delta and C fibers) in the peripheral nervous system transmit nerve impulses (often originating from peripheral mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors) through synapses in the spinal cord’s dorsal horn through (but not exclusively through) the spinothalamic tracts to the brain’s higher centers, where nociception is converted to pain with all of its cognitive and emotional ramifications.

| PAIN CATEGORY | DEFINITION AND EXAMPLES | CHARACTERISTICS |

|---|---|---|

| Somatic |

The Assessment and Measurement of Pain in Children

Age-Specific and Developmentally Specific Measures

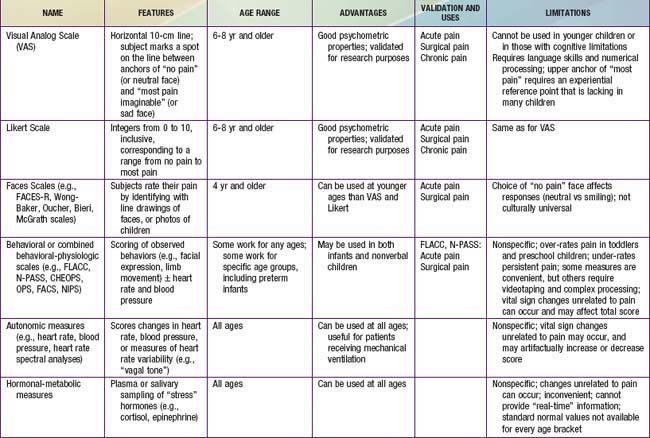

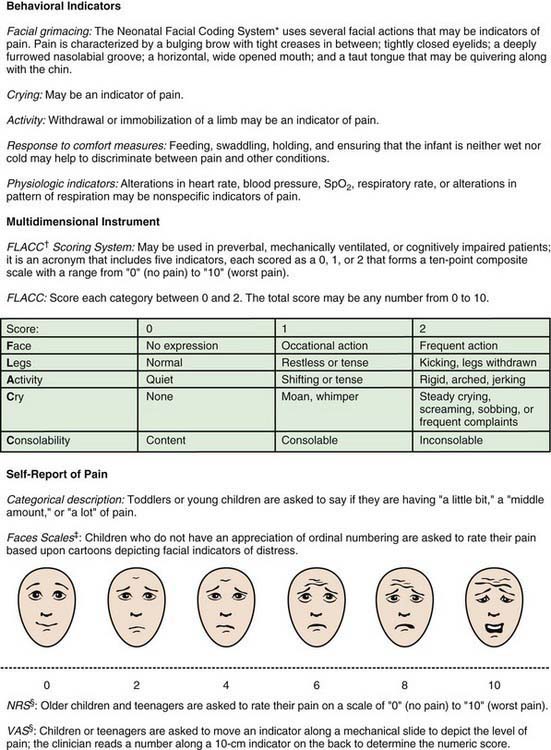

Because infants, young children, and nonverbal children cannot express the quantity of pain they experience, several pain scales have been devised in an attempt to quantify pain in these populations (Fig. 71-2; Table 71-2).

Figure 71-2 Clinically useful pain assessment tools.

(Adapted from Burg FD, Ingelfinger JR, Polin RA, et al, editors: Current pediatric therapy, ed 18, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders/Elsevier, p 16; and Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford P, et al: The Faces Pain Scale—revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement, Pain 93:173–183, 2001.)

The Older Child

Children 3-7 yr old become increasingly articulate in describing the intensity, location, and quality of pain. Pain is occasionally referred to adjacent areas; referral of hip pain to the leg or knee is common in this age range. Self-report measures for children this age include using drawings, pictures of faces, or graded color intensities. Children age 8 yr and older can usually use verbal scales or visual analog pain scales (VASs) accurately (see Fig. 71-2). Verbal numerical ratings are preferred and considered the gold standard; valid and reliable ratings are for children 8 yr and older. The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) consists of numbers from 0 to 10, in which 0 represents no pain and 10 represents very severe pain. There is debate about the label for the highest pain rating, but the current agreement is NOT to use the worst pain possible, because children can always imagine a greater pain. In the USA, regularly documented pain assessments are required for hospitalized children and children attending outpatient hospital clinics and emergency departments. Pain scores do not always correlate with changes in heart rate or blood pressure.

The Treatment of Pain

Both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches to pain management should be considered for all pain treatment plans. Many simple interventions designed to promote relaxation and patient control can be expected to work synergistically with pain medications for optimal relief of pain and related distress. Psychologic and developmental comorbidities affect the child’s experience of pain and ability to tolerate and cope with it. Thus, it is important to assess a child for evidence of situational anxiety and/or anxiety disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety, separation anxiety, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Chapter 23). Depression assessment should include current suicidal ideation and intent as well as past history of suicidal gestures or attempts (Chapters 24 and 25). Developmental assessment includes evaluating for specific learning disorders, Asperger disorder, and evidence of pervasive developmental disorders in general, including autism spectrum disorders (Chapter 28). All psychologic and developmental comorbidities should be determined and addressed, to adequately treat the child in pain or to reduce the risk of the child’s developing ongoing pain after surgery, trauma, or even invasive medical procedures.

Pharmacologic Treatment of Pain

Acetaminophen, Aspirin, and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Acetaminophen (APAP) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have replaced aspirin as the most commonly used antipyretics and oral, nonopioid analgesics (Table 71-3).

| MEDICATION | DOSAGE | COMMENT(S) |

|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen |

FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; IV, intravenous(ly): NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PDD, pervasive developmental disorder; PDR, Physicians’ Desk Reference; QTc, corrected QT interval on an electrocardiogram; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Acetaminophen, a generally safe, nonopioid analgesic and antipyretic, has the advantage of rectal and oral routes of administration, is expected to be available soon also as an intravenous (IV) preparation in the USA, as it is now in Europe. Acetaminophen is not associated with the gastrointestinal or antiplatelet effects of aspirin and NSAIDs, making it a particularly useful drug in patients with cancer. Unlike aspirin and NSAIDs, acetaminophen has only mild anti-inflammatory action. Acetaminophen toxicity can result from either, large single doses or cumulative, excessive dosing over days or weeks (Chapters 58 and 355). A single, massive overdose overwhelms the normal glucuronidation and sulfation metabolic pathways in the liver, whereas long-term overdosing exhausts supplies of the sulfhydryl donor glutathione, leading to alternative cytochrome P-450 catalyzed oxidative metabolism and the production of the hepatotoxic metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). Toxicity manifests as fulminant hepatic necrosis and failure in infants, children, and adults. Drug biotransformation processes are immature in neonates, very active in young children, and somewhat less active in adults. Young children are more resistant to acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity than adults as a result of metabolism differences: Sulfation predominates over glucuronidation in young children, leading to a reduction in NAPQI production.

Aspirin (ASA) is indicated for certain rheumatologic conditions and for inhibition of platelet adhesiveness, as in the treatment of Kawasaki disease. Concerns about Reye syndrome have resulted in a substantial decline in pediatric aspirin use (Chapter 349).

Adverse effects of NSAIDs are uncommon, but they may be serious when they occur. They include gastritis with pain and bleeding; decreased renal blood flow that may reduce glomerular filtration and enhance sodium reabsorption, in some cases leading to tubular necrosis; hepatic dysfunction and liver failure; and inhibition of platelet function. Although the overall incidence of bleeding is very low, NSAIDs should not be used in the child with a bleeding diathesis or at risk for bleeding or when surgical hemostasis is a prominent concern, such as after tonsillectomy. Renal injury from short-term use of ibuprofen in euvolemic children is quite rare; the risk is increased by hypovolemia or cardiac dysfunction. The safety of both ibuprofen and acetaminophen for short-term use is well established (see Table 71-3).

Opioids

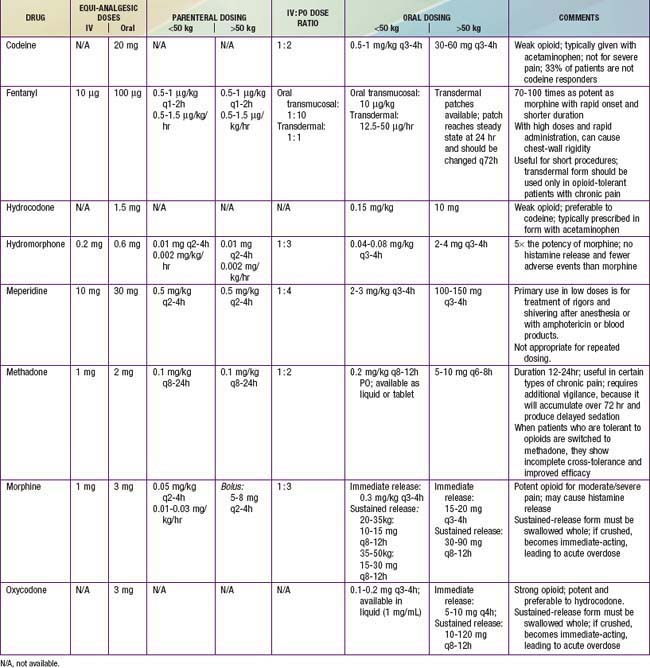

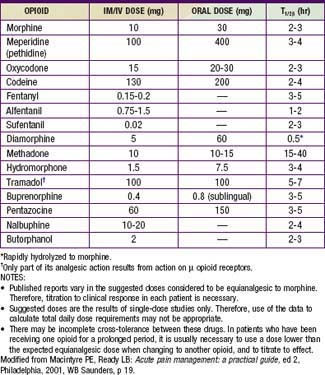

Opioids are analgesic substances either derived from the opium poppy (opiates) or synthesized to have a similar chemical structure and mechanism of action (opioids). The older, pejorative term narcotics should not be used for these agents, because it connotes criminality and lacks pharmacologic descriptive specificity. Opioids are administered for moderate and severe pain, such as acute postoperative pain, sickle cell crisis pain, and cancer pain. Opioids can be administered by the oral, rectal, oral transmucosal, transdermal, intranasal, IV, epidural, intrathecal, subcutaneous, or intramuscular route. Historically, infants and young children have been underdosed with opioids for fear of significant respiratory side effects. With proper understanding of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics of opioids, children can receive effective relief of pain and suffering with a good margin of safety (Tables 71-4 to 71-7).

Table 71-5 PRACTICAL ASPECTS OF PRESCRIBING OPIOIDS

* Avoid in patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors.

† May be associated with extrapyramidal side effects, which may be more commonly seen in children than in adults.

Modified from Burg FD, Ingelfinger JR, Polin RA, et al, editors: Current pediatric therapy, ed 18, Philadelphia, 2006, Saunders/Elsevier, p 16.

Optimal use of opioids requires proactive and anticipatory management of side effects (see Table 71-6). Common side effects include constipation, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention, and pruritus. The most common, troubling but treatable side effect is constipation. Stool softeners and stimulant laxatives should be administered to most patients receiving opioids for more than a few days. Constipation also remains a problem with long-term opioid administration. A peripherally acting opiate µ receptor antagonist, methylnaltrexone, promptly and effectively reverses opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic pain who are receiving opioids daily. The side effect of nausea typically subsides with long-term dosing, but it may require treatment with antiemetics, such as a phenothiazine, butyrophenones, antihistamines, or a serotonin receptor antagonist such as ondansetron or granisetron. Pruritus and other complications during patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with opioids may be effectively managed by low-dose IV naloxone (see Table 71-6).

One of the potent barriers to effective management of pain with opioids is the unrealistic fear of addiction held by many prescribing pediatricians and parents. Pediatricians should understand the phenomena of tolerance, dependence, withdrawal, and addiction (see Table 71-5) and should know that the rational short- or long-term use of opioids in children does not lead to a predilection or risk of addiction in a child not otherwise at risk by virtue of genetic background and social milieu. It is important for pediatricians to realize that even patients with recognized substance-abuse diagnoses are entitled to effective analgesic management, which often includes the use of opioids. When there are legitimate concerns about addiction in a patient, then safe, effective opioid pain management is often best managed by specialists in pain management and/or addictionology.

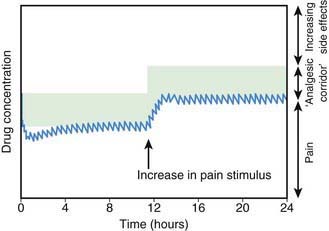

There is no longer a reason to administer opioids by intramuscular injection. Continuous IV infusion of opioids is one, effective option that permits more constant plasma concentrations and clinical effects than intermittent IV bolus dosing, without the pain associated with intramuscular injection. The most common approach in pediatric centers is to administer a low-dose basal opioid infusion, while permitting patients to use a PCA device to titrate the dosage above the infusion (Chapter 70; Fig. 71-3). Compared with children given intermittent intramuscular morphine, children using PCA reported better pain scores. PCA has several other advantages: (1) dosing can be adjusted to account for individual pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variation and for changing pain intensity during the day, (2) psychologically, the patient is more in control, actively coping with the pain, (3) overall opioid consumption is lower, (4) fewer side effects occur, and (5) patient satisfaction is generally much higher. Children as young as 5-6 yr can effectively use PCA. The device can be activated by parents or nurses—the latter practice known as PCA-by-proxy (PCA-P); PCA-P produces analgesia in a safe, effective manner for children who cannot activate the PCA demand button themselves because they are too young or intellectually or physically impaired. PCA overdoses occur when well-meaning, inadequately instructed parents pushed the PCA button in medically complicated situations with or without the use of PCA-P, highlighting the need for patient and family education, the use of protocols, and adequate nursing supervision.

Local Anesthetics

Local anesthetics are widely used in children for topical application, cutaneous infiltration, peripheral nerve block, epidural neuraxial blocks, intrathecal infusions, and IV infusions (Chapter 70; Table 71-8). Local anesthetics can be used with excellent safety and effectiveness. Excessive systemic concentrations can cause seizures, central nervous system (CNS) depression, arrhythmia, or cardiac depression. Unlike opioids, local anesthetics require a strict maximum dosing schedule. Pediatricians should be aware of the need to calculate these doses and adhere to guidelines. Topical local anesthetic preparations can reduce pain in diverse circumstances: suturing of lacerations, placement of peripheral IV catheters, lumbar punctures, and accessing of indwelling central venous ports. The application of tetracaine, epinephrine, and cocaine (TAC) results in good anesthesia for suturing wounds, but TAC should not be used on mucous membranes. Combinations of tetracaine with phenylephrine and lidocaine-epinephrine-tetracaine are equally as effective as TAC, eliminating the need to use a controlled substance (cocaine). EMLA, a topical eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine used to anesthetize intact skin, is commonly applied for venipuncture, lumbar puncture, and other needle procedures. EMLA is generally safe for use in neonates, but it has been associated with prilocaine-induced methemoglobinemia. In circumcision, EMLA is more effective than placebo in providing analgesia, but probably less effective than ring block of the penis. EMLA should be used cautiously for circumcision, because its use may cause redness and blistering on the penis. A small area should be tested for hypersensitivity before EMLA is more widely applied. Lidocaine cream, 5%, has replaced EMLA in many pediatric centers. Lidocaine is the most commonly used local anesthetic for cutaneous infiltration. Maximum safe doses of lidocaine are 5 mg/kg without epinephrine and 7 mg/kg with epinephrine. Although concentrated solutions (2%) are commonly available from hospital pharmacies, more dilute solutions such as 0.25% and 0.5% are as equally as effective as 1-2% solutions. The diluted solutions cause less burning discomfort on injection and permit use of larger volumes without achieving toxic doses. In the surgical setting, cutaneous infiltration is more often performed with bupivacaine 0.25% or ropivacaine 0.2% because of the much longer duration of effect. The maximum dose of these long-acting amide anesthetics is 2 to 3 mg/kg.

| Amides: Are metabolized in the liver and the elimination half-lives vary from about 1.5 hr to 3.5 hr |

Modified from Macintyre PE, Ready LB: Acute pain management: a practical guide, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2001, WB Saunders, p 19.

Neuropathic pain often responds well to the local application of a lidocaine topical patch (Lidoderm) for 12 hr per day (Table 71-9). Peripheral neuropathic pain may also respond well to IV lidocaine infusions, which may be used in hospital settings for refractory pain, complex regional pain syndromes, and pain associated with malignancies or the therapy of malignancies, such as oral mucositis following bone marrow transplantation. In these instances, 1 to 2 mg/kg/hr should be administered, and the infusion titrated to achieve a blood lidocaine level in the 2 to 5 µg/mL range, with use of twice daily therapeutic blood monitoring. Approaches to central neuropathic pain are listed in Table 71-10.

Table 71-9 EXAMPLES OF NEUROPATHIC PAIN SYNDROMES

PERIPHERAL NERVOUS SYSTEM FOCAL AND MULTIFOCAL LESIONS

PERIPHERAL NERVOUS SYSTEM GENERALIZED POLYNEUROPATHIES

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM LESIONS

Modified from Freynhagen R, Bennett MI: Diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain, BMJ 339:b3002, 2009.

Table 71-10 TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CENTRAL NEUROPATHIC PAIN ADAPTED FROM CURRENT EVIDENCE-BASED LITERATURE

| MEDICATION CLASS/DRUG | RECOMMENDED STAGE OF TREATMENT |

|---|---|

| ANTIDEPRESSANTS | |

| Tricyclics (amitriptyline) | First or second |

| Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (duloxetine, venlafaxine) | First or second |

| ANTICONVULSANTS | |

| Pregabalin | First or second |

| Gabapentin | First or second |

| Lamotrigine | Second or third (in pain after stroke) |

| Valproate | Third |

| OPIOIDS* | |

| Levorphanol | |

| MISCELLANEOUS | |

| Cannabinoids | Second (in multiple sclerosis) |

| Mexiletine | Third |

* Second or third (no specification).

From Freynhagen R, Bennett MI: Diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain, BMJ 339:b3002, 2009.

Unconventional Medications in Pediatric Pain

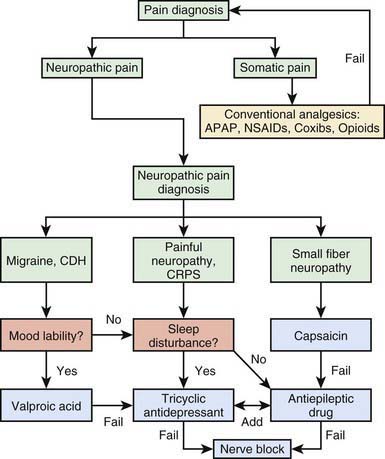

The unconventional analgesics are generally used to manage neuropathic pain conditions, migraine disorders, fibromyalgia syndrome, and some forms of functional chronic abdominal pain syndromes, but they are generally not used to manage surgical, somatic, or musculoskeletal pain. Figure 71-4 presents a decision-making tree that will help the physician select the appropriate analgesic category for various types of pain.

Antidepressant Medications

Invasive Interventions in Treating Pain

Interventional neuraxial and peripheral nerve blocks provide intraoperative anesthesia, postoperative analgesia (Chapter 70), treatment of acute pain (e.g., long bone fracture and the pain of acute pancreatitis), and contribute to the management of chronic pain (e.g., headaches, abdominal pain, complex regional pain syndromes [CRPS], and cancer pain).

Considerations for Special Pediatric Populations

Children with Cancer Pain

The World Health Organization (WHO) proposed an analgesic therapy model for cancer pain known as the analgesic ladder (Table 71-11). Designed to guide therapy in the Third World, this ladder consists of a hierarchy of oral pharmacologic interventions intended to treat pain of increasing magnitude. The hierarchy ignores modalities such as the use of nonconventional analgesics and interventional pain procedures, which are within the capability of physicians to prescribe in developed countries. Nevertheless, because oral medications are simple and efficacious, especially for home use, the ladder presents a framework for rationally using them before applying other drugs and techniques of drug administration.

Table 71-11 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION ANALGESIC LADDER FOR CANCER PAIN

STEP 1

Patients who present with mild to moderate pain should be treated with a nonopioid.

STEP 2

Patients who present with moderate to severe pain or for whom the step 1 regimen fails should be treated with an oral opioid for moderate pain combined with a nonopioid analgesic.

STEP 3

Patients who present with very severe pain or for whom the step 2 regimen fails should be treated with an opioid used for severe pain, with or without a nonopioid analgesic.

Children with Pain Associated with Advanced Disease

Patients with advanced diseases, including cancer, AIDS, neurodegenerative disorders, and cystic fibrosis, need palliative care approaches that focus on optimal quality of life. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic means of management of pain and other distressing symptoms are palliative care’s key components. Differences among these conditions that relate to the progression of underlying illness, associated distressing symptoms, and common emotional responses should shape individual treatment plans (Chapter 40). More than 90% of children and adolescents dying of cancer can be made comfortable by standard escalation of opioids according to the WHO protocol. A small subgroup (5%) has enormous opioid dose escalation to >100 times the standard morphine or other opiate infusion rate. In most of these cases, there is spread of solid tumors to the spinal cord, roots, or plexus, and signs of neuropathic pain are evident. Methadone given orally is often used in palliative care because of its long half-life and its targets at both opioid and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors. The type of pain experienced by the patient (neuropathic, myofascial) should determine the need for adjunctive agents. Complementary measures, such as massage, hypnotherapy, and/or spiritual care, should also be considered in palliative care. Although the oral route of opioid administration should be encouraged, especially to facilitate care at home if possible, some children are unable to take oral opioids. Intravenous infusion with a PCA is the next choice. Small, portable infusion pumps are convenient for home use. If venous access is limited, a useful alternative is to administer opioids (especially morphine or hydromorphone, but not methadone or meperidine) through continuous subcutaneous infusion, with or without a bolus option. A small (e.g., 22-gauge) cannula is placed under the skin and secured on the thorax, abdomen, or thigh. Sites may be changed every 3-7 days, as needed. Alternative routes for opioids include the transdermal and oral transmucosal routes. These latter routes are preferred over IV and subcutaneous drug delivery when the patient is being treated at home.

Examples of Chronic and Recurrent Pain Syndromes

Complex Regional Pain Syndromes

Neuropathic pain is caused by abnormal excitability in the peripheral or central nervous system that may persist after an injury heals or inflammation subsides. The pain, which can be acute or chronic, is often described as burning or stabbing and may be associated with cutaneous hypersensitivity (allodynia). Neuropathic pain conditions may be responsible for >35% of referrals to chronic pain clinics, conditions that commonly include post-traumatic and postsurgical peripheral nerve injuries, phantom pain after amputation, pain after spinal cord injury, and pain due to metabolic neuropathies. Neuropathic pain typically responds poorly to opioids. In adults, evidence suggests the efficacy of TCAs (nortriptyline, amitriptyline) and anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin) for treatment of neuropathic pain (see Tables 71-9 and 71-10).

The syndromes of CRPS type 2 and CRPS type 1 are virtually identical, except that the former is associated with a well-defined peripheral nerve injury. Treatment of CRPS in children has been extrapolated from that in adults, with some low-level evidence for efficacy of physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, nerve blocks, TCAs, gabapentin, and some other related drugs. All experts in pediatric pain management agree on the value of aggressive physical therapy. Some centers provide aggressive therapy without the use of pharmacologic agents or interventional nerve blocks; unfortunately, recurrent episodes may be seen in up to 50% of patients. Physical therapy can be extraordinarily painful for children to endure; it is tolerated only by the most stoic and motivated patients. If children have difficulty enduring the pain, there is a well-established role for using pharmacologic agents with or without peripheral or central neuraxial nerve blocks to render the affected limb sufficiently analgesic so that physical therapy can be tolerated. Pharmacologic interventions include the use of AEDs such as gabapentin and/or TCAs such as amitriptyline (see Fig. 71-4). Although there is clear evidence of a peripheral inflammatory component of CRPS, with release of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators from the peripheral nervous system in the affected limb, the use of anti-inflammatory agents has been disappointing. Commonly used nerve block techniques include sympathetic nerve blocks, IV regional anesthetics, epidural analgesia, and peripheral nerve blocks. In extreme and refractory cases, more invasive strategies have been reported, including surgical sympathectomy and spinal cord stimulation. Although an array of treatments have some benefit, the mainstay of treatment remains physical therapy emphasizing desensitization, strengthening, and functional improvement. Additionally, pharmacologic agents and psychologic and complementary therapies are important components of a treatment plan. Invasive techniques, although not curative, are valuable if they permit the performance of frequent and aggressive physical therapy that cannot be carried out otherwise. Some children with CRPS become so easily sensitized that persistent and bothersome pain may develop at the site of the invasive procedure. A good biopsychosocial evaluation will help determine the orientation of the treatment components.

Erythromelalgia

Erythromelalgia in children is generally primary, whereas in adults it may be either primary or secondary to malignancy. Patients with this disorder exhibit red, warm, hyperperfused distal limbs. The disorder is usually bilateral, and it may involve either or both the hands and feet. Patients perceive burning pain and typically seek relief by immersing the affected extremities in ice water, sometimes so often and for so long so that skin pathology results. It is easy to distinguish erythromelalgia (or related syndromes) from CRPS. The limb afflicted with CRPS is typically cold and cyanotic, the disease is typically unilateral, and children with CRPS have cold allodynia, making immersion in cold water exquisitely painful; in erythromelalgia, ice water immersion is analgesic. The evaluation of hyperperfused limbs with burning pain should include genetic testing for Fabry’s disease (FD) and screening for hematologic malignancies, with diagnosis of primary erythromelalgia being one of exclusion. The definitive treatment of FD includes enzyme replacement as disease-modifying treatment and administration of neuropathic pain medications, such as gabapentin, although the success of anti–neuropathic pain drugs in small-fiber neuropathies has not been impressive. The treatment of erythromelalgia is far more problematic. Anti–neuropathic pain medications, such as AEDs and TCAs are typically prescribed but rarely helpful (see Fig. 71-4). The pain responds well to regional anesthetic nerve blocks, but it returns immediately when the effects of the nerve block resolve. In contrast, in other neuropathic syndromes, the analgesia usually (and inexplicably) persists well after the resolution of the pharmacologic nerve block. Aspirin and even nitroprusside infusions have been reported to be of benefit with secondary erythromelalgia, but they have not been reported to be helpful in children with primary erythromelalgia. There are case reports in adults and clinical experience in children suggesting that periodic treatment with high-dose capsaicin cream is effective in alleviating the burning pain and disability of erythromelalgia. Capsaicin (essence of chili pepper) cream is a vanilloid receptor (TRPV1) agonist that depletes small-fiber peripheral nerve endings of the neurotransmitter substance P, which are important in the generation and transmission of nociceptive impulses. Once depleted, these nerve endings are no longer capable of generating spontaneous pain until the receptors regenerate, a process that takes many months.

2006 Acupuncture. Med Lett. 2006;48:38.

American Pain Society. Guideline for the management of cancer pain in adults and children. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2005.

Becker G, Blum HE. Novel opioid antagonists for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction and postoperative ileus. Lancet. 2009;373:1198-1206.

Breau LM, Burkitt C. Assessing pain in children with intellectual disabilities. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14:116-120.

Breau LM, Camfield CS, Symons FJ, et al. Relation between pain and self-injurious behavior in nonverbal children with severe cognitive impairments. J Pediatr. 2003;142:498-503.

Brousseau DC, McCarver DG, Drendel AL, et al. The effect of CYP2D6 polymorphisms on the response to pain treatment for pediatric sickle cell pain crisis. J Pediatr. 2007;150:623-626.

Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

Colvin L, Forbes K, Fallon M. Difficult pain. BMJ. 2006;332:1081-1083.

Drendel AL, Gorelick MH, Weisman SJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen with codeine for acute pediatric arm fracture pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:553-560.

Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based-recommendations. Pain. 2007;132:237-251.

Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Williams AC, et al: Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (15):CD003968, 2009.

Freynhagen R, Bennett MI. Diagnosis and management of neuropathic pain. BMJ. 2009;339:b3002.

Harrop JE. Management of pain in childhood. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2007;92:ep101-ep108.

Hijazi R, Taylor D, Richardson J. Effect of topical alkane vapocoolant spray on pain with intravenous cannulation in patients in emergency departments: randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;228:b215.

Jalan R, Williams R, Bernuau J. Paracetamol: are therapeutic doses entirely safe? Lancet. 2006;368:2195-2196.

Marco CA, Plewa MC, Buderer N, et al. Self-reported pain sores in the emergency department: lack of association with vital signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:974-979.

Maxwell LG, Kaufmann SC, Bitzer S, et al. The effects of a small-dose naloxone infusion on opioid-induced side effects and analgesia in children and adolescents treated with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: a double-blind, prospective, randomized, controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:953-958.

Quigley C. The role of opioids in cancer pain. BMJ. 2005;331:825-829.

Ramamurthi RJ, Krane EJ. Local anesthetic pharmacology in pediatric anesthesia. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2007;11:229-234.

Shann F. Suckling and sugar reduce pain in babies. Lancet. 2007;369:721-722.

Symons FJ, Harper VN, McGrath PJ, et al. Evidence of increased non-verbal behavioral signs of pain in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders and chronic self-injury. Res Dev Disabil. 2009;30:521-528.

Uman LS, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, et al. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents: an abbreviated Cochrane review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:842-854.

Viscusi ER. Patient-controlled drug delivery for acute postoperative pain management: a review of current and emerging technologies. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:146-158.

Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S, Tait AR, et al. A comparison of the clinical utility of pain assessment tools for children with cognitive impairment. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:72-78.

Von Baeyer CL, Spagrud LJ, McCormick JC, et al. Three new datasets supporting use of the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS-11) for children’s self-reports of pain intensity. Pain. 2009;143:223-227.

Walker SM. Pain in children: recent advances and ongoing challenges. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:101-110.

White A, Cummings M. Does acupuncture relieve pain? BMJ. 2009;338:303-304.

Zeltzer LK, Schlank CB. Conquering your child’s chronic pain: a pediatrician’s guide for reclaiming a normal childhood. New York: HarperCollins; 2005.