CHAPTER 47 Pediatric Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

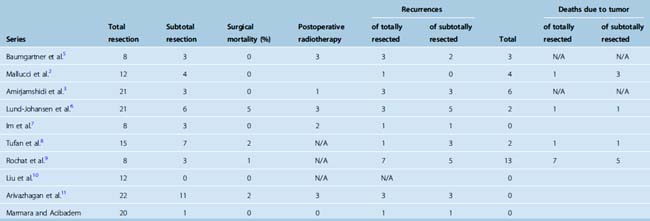

Meningiomas in the pediatric population are similar in many ways to those in their adult counterparts, although several characteristics are unique to this group. These, including the lack of female predominance, larger size at presentation, as well as lack of dural attachments and unusual anatomic locations, are discussed in this chapter. Whereas intracranial meningioma is one of the most common tumors in adults, they are uncommon in children, accounting for only 2% to 4.2% of all pediatric tumors in most series.1,2 As these lesions are relatively uncommon, they have created some controversies in particular with regard to their recurrence and long-term outcomes due to conclusions drawn on small series reported before modern imaging and surgical techniques. Nonetheless, many series reported recurrences even with totally resected tumors,3 which may imply the need for ongoing and life long follow-up. Many studies during the last 30 years have reported on this entity, which had been considered very rare in the past1,4 (Table 47-1). These series also suggested a poor prognosis; however, inclusion of malignant meningeal tumors and patients with neurofibromatosis may be the explanation for this conclusion1 (Tables 47-1, 47-2, and 47-3).

Table 47-1 shows the previously reported series of pediatric meningiomas as well as our own series of 21 pediatric meningiomas from a total of 928 tumors treated at Marmara University Medical Center and Acibadem University.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

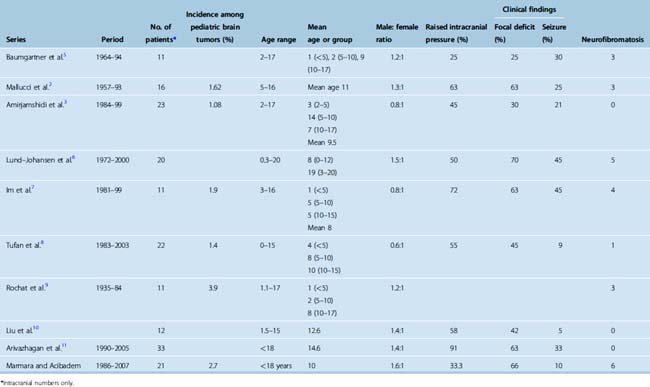

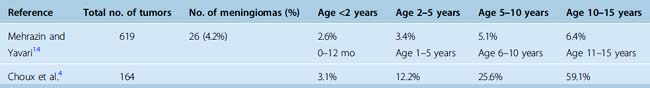

The incidence of meningiomas in pediatric populations in most series (see Table 47-1) ranges between 1% and 2% of all pediatric intracranial tumors in patients younger than 15 years of age as seen previously1 in the studies listed in Table 47-1. Some studies found a slightly higher incidence. In an epidemiologic review of 1195 cases from a single institution, Rosemberg and Fujiwara reported the incidence of pediatric central nervous system (CNS) tumors.12 They reported a 3% (32/1058) incidence of intracranial meningiomas. The relative frequency of grade I and II meningiomas was also reported by Rickert and Paulus13 in a combined series of 319 patients, which were 2.2% and 2.5% in newborn to 14- and newborn to 17-year-olds, respectively. The incidence of meningiomas relative to different pediatric age groups has been reported by several groups4,14 (Table 47-4) and indicates the increasing incidence of meningioma with increased age in the pediatric group. These data indicate that pediatric meningiomas are not as rare as previously thought.

Lack of female predominance is well documented, and some studies found a slightly higher male representation in this group.1,6,15,16 This was also noted in the series reviewed in this chapter as shown in Table 47-1, where there was slight male predominance of 1.13:1 ratio.2,3,5–11 This is thought to be due to the lack of hormonal influence in the prepubertal age group, as hormonal effects beginning in this age would not manifest themselves for several years.17

The mean age at presentation is mostly reported at around 11 years of age and is generally later than in most other pediatric CNS tumors,6,8,16 Another combined review of 84 patients younger than 19 years with menigiomas has found the peak age to be 12 years.17

Association with neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1 and 2 is also well established in the literature. In a review of four series with 126 patients, 1 in 4 children with meningioma were found to have NF2.17 The number of patients with neurofibromatosis in recent articles listed in Table 47-1 was only 16/159, or 11% of the total.

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

Radiation and neurofibromatosis are recognized as predisposing factors,2,6,18 while the role of trauma has been controversial. Trauma as a risk factor for developing meningiomas was first suggested by Cushing and Eisenhart; however, it is not substantiated in more recent reports.19

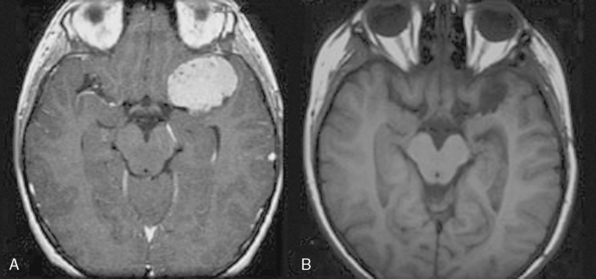

The role of radiation in developing meningiomas is well established (Fig. 47-1). The initial major report indicating this connection was the study of children irradiated for tinea capitis in Israel.20 In this study 10,834 children who had undergone low-dose (approximately 850 cGy) ionizing radiation were compared with 10,834 age- and sex-matched controls. The study found a fourfold increased risk of developing meningioma in the irradiated group,20 which increased with increased dosage.

In a comprehensive study of radiation-induced brain tumors in childhood, Pettorini and colleagues21 reviewed the literature between 1960 and 2007. Review of the pediatric population from 60 articles resulted in 142 cases of which 33 were grade I and 7 were atypical meningiomas. The median age at radiation for grade I tumors was 5.4 years and that for atypical tumors was 5.1 years of age with a latency period of 13.7 years (range, 6 months–28 years) and 21.1 years (range 8–63 years) for grade I and II, respectively. Interestingly, the investigators did not find any correlation between the dose and the malignancy of the secondary tumor, although more than two thirds of both grade I and II meningiomas were exposed to high-dose radiotherapy.

Chromosomal abnormalities are also well associated with meningiomas, and the association between NF2 and meningioma is covered in Chapter 48. An abnormality of chromosome 22 has been reported for both sporadic and NF2-associated meningiomas. It is important to mention that meningioma was the first solid tumor to be associated with cytogenetic abnormalities, with most tumors showing monosomy of chromosome 22 and some with partial deletion or rearrangement of 22q.22 Between 40% and 60% of meningiomas showed allelic losses of this chromosome.22 Other chromosomal abnormalities in pediatric meningiomas involve chromosome 1p (in 5 of 13 cases) and chromosome 6q (4 of 13 cases) as reported by Bhattacharjee and colleagues.22

In two large series Merten and colleagues23 (48 patients) and Deen and colleagues24 (51 patients) showed 23% and 24% of patients respectively were NF2 positive. Erdicler and colleagues15 reported 41% of 27 cases were associated with neurofibromatosis, of which 58% were NF1 and 42% were NF2.

Further, these children have a higher incidence of extracranial, intraocular, and multifocal meningiomas, indicating the need for close monitoring of these patients as well as investigating children with meningioma for the presence of neurofibromatosis. One should also keep in mind that NF2-related tumors are indolent5 and therefore conservative management may be an option depending on the clinical situation.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Signs and Symptoms

As expected in the case of any space-occupying intracranial mass, symptoms of raised intracranial pressure including nausea, vomiting, and headache are the common presenting clinical features in most series, as reported in a review of 10 series17 in which 45% of patients presented with raised intracranial pressure (ICP) symptoms, whereas focal neurologic signs were the presenting problem in only 25% of 184 patients in this review. Seizures as presenting symptom are less frequent and may suggest a supratentorial site, in particular in the temporal location.5,8

The focal signs and symptoms depend on the location of the tumor causing localized irritation of the surrounding eloquent brain. In a combined series consisting of 166 children with meningioma, Liu and colleagues10 found signs and symptoms of raised ICP in 62%, cranial nerve palsy in 28%, motor deficit in 19%, and epilepsy in 25% of cases, with 19% of patients presenting with visual disturbances.

In infancy, increasing head circumference may be the only sign.1,4,25 Nonspecific symptoms and signs such as irritability and poor feeding due to raised ICP may also be present. The presence of homonymous hemianopia in association with intraventricular meningiomas was noted by Hertz and colleagues.16

The most common presenting complaint from the series we reviewed (see Table 47-1) related to raised ICP (51%), followed by focal neurologic deficit (42.5%), and seizure in only 18% of children with meningioma.

LOCATIONS

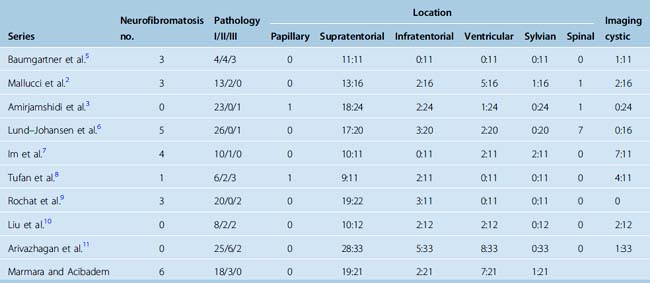

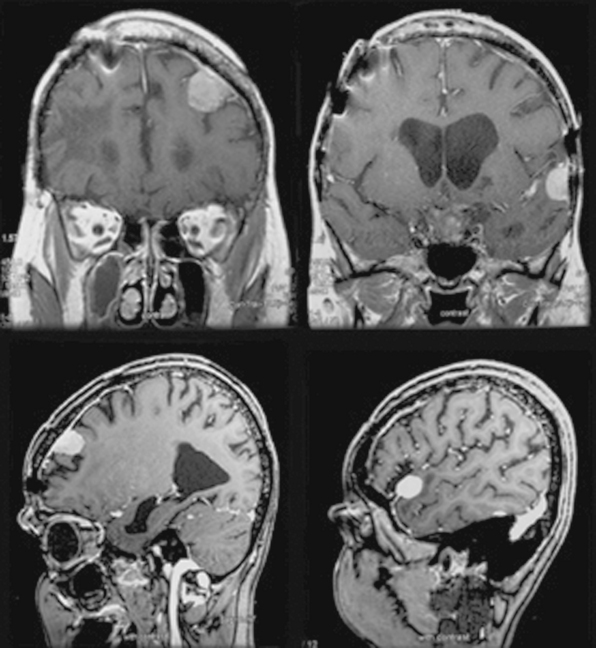

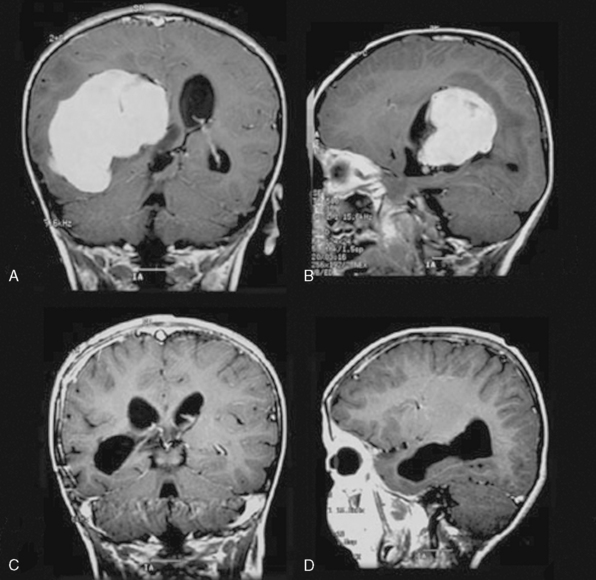

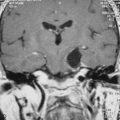

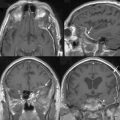

In terms of location, the distribution of pediatric meningiomas is similar to that of adult tumors. However, in contrast to adult meningiomas there appears to be a higher number of intraventricular (Fig. 47-2), sylvian (Fig. 47-3), and infratentorial tumors in children from reported series.

Lack of dural attachment is reported in many series.1,9,26 Drake and colleagues1 reported 23% of the tumors in their series which did not show dural attchment, and Merten and colleagues23 and Doty and colleagues27 11% and 15%, respectively. These tumors were mostly sylvian fissure tumors while intraventricular tumors were excluded. Overall incidence of sylvian fissure meningiomas in the review by Drake and colleagues1 of 207 cases was 3%.

Increased incidence of intraventricular location has also commonly been reported in pediatric menigiomas. In two larger series excluding spinal cases, Merten and colleagues23 and Deen and colleagues28 had 17% (8/47) and 4.8% (2/41) intraventricular tumors. However, Deen and colleagues,24 calculating this proportion from the total number of their cases (51 patients) including 10 spinal cases, gave a lower percentage of 3.9% which they claim to be almost the same as in adult series. Among 159 patients included in Table 47-1 there were only 3 sylvian, but 20 (12.5%) intraventricular meningiomas were noted.

Intraparenchymal location with no dural attachment comprised 5% of 166 patients collectively reported by Liu and colleagues10 from mostly Asian series. Intraventricular location in this report was present in 15% of cases.

Infratentorial meningiomas (see Fig. 47-2) also have been reported to occur more commonly in children than in adults. In our review of the above series (see Table 47-1) they represented 18 of 156 (11%) of cases reported. The incidence of skull-base meningiomas from 4 series consisting of 78 patients was 22%.3,7–9

Spinal meningiomas are very rare, although one of the largest studies by Deen and colleagues24 reported 10 spinal tumors out of 51 cases. Also, in the Lund-Johanson6 series, 7 out of 27 were spinal meningiomas. These tumors are also reported to have the sex distribution as intracranial group with male predominance, but similar to adult cases they are reported to more common in thoracic region.1 In series reviewed in Table 47-1, only 9 out of 156 (5.6%) cases were spinal meningiomas.

IMAGING

On plain radiographs, many series have reported a higher percentage of calcification, as well as calvarial erosion and hyperostosis. Choux and colleagues4 reported findings of hyperostosis or erosion in up to one third in their series of 16 patients. Abnormal calcifications were seen in 21% of cases reported.9 Skull radiographic abnormalities showing hyperostosis, calvarial bulging and focal erosion were seen in 7 out of 11 cases reported by Im and colleagues7 and 7 out of 33 tumors in another series.11

The typical computed tomography (CT) features of pediatric meningiomas are similar to those in adults. These include presence of an extra-axial lesion, with associated hyperostosis, irregularity of underlying cortex, and calcification within the tumor in up to 25% of cases demonstrated as hyperdense areas. An extra-axial mass is identified by its broad base toward the dural surface, causing displacement of gray matter (“buckled”) and there may be a thin cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rim between the tumor and the cortex. More than 90% of these lesions enhance strongly with contrast.21 Other described findings on CT scans include sharp and lobulated margins and homogeneous postcontrast enhancement, with limited peritumoral edema which were found in all 24 cases reported in one study,3 while in the series of Im and colleagues7 examination by CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed about 20% of tumors with poor demarcation, and less than 10% poorly enhancing with contrast.7

Cystic areas have been reported in up to 3% of mixed series,21 although their presence in pediatric meningiomas is commonly reported to be higher.17 In combined series Artico and colleagues29 found 25 cystic meningiomas in 210 reported cases representing 12% of these tumors. Also in other studies cystic tumors have been reported in up to 8% versus 3% to 5% in adults,15,17,20 and in 155 patients reviewed by Liu and colleagues,10 21% had cystic changes.

One of the commonly reported features of pediatric menigiomas is their large size at presentation. In their combined series of 166 patients, Liu and colleagues10 reported the mean diameter of 5.2 cm with the range of 2 to 11 cm.

The clinical significance of cystic changes is unclear from the literature, although Tufan and colleagues8 reported 4 cystic tumors out of 11 reported cases, all of which were grade II or III. The cystic feature is best appreciated on MRI.

Usual MRI features of meningiomas are covered in Chapter 14. On standard sequences these lesions typically appear isointense or occasionally hypointense to the cortex on T1-weighted images and hyperintense or mixed intensity on T2 images. The majority of these lesions (>90%) enhance strongly with contrast.21 The extent of edema (50%–65%)21 and the presence of a CSF rim around the tumor is also better seen on MRI (T2-weighted), which can confirm the extra-axial nature of these lesions.

One of the features that has commonly been reported in the literature is absence of a dural tail in a high percentage of pediatric meningiomas. Dural thickening or “tail” is the best diagnostic feature of meningiomas and is reported in 35% to 80% of cases.21 However, it is not pathognomic for meningiomas.

As these lesions are uncommon and can present in unusual locations (infratentorial, intraventricular or intraparenchymal), differentiating from other lesions can be difficult on routine MRI sequences. Rutten and colleagues18 have described MR spectroscopy features that can be useful in differentiating meningiomas from other lesions in particular metastases and gliomas. These are described as low N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) and free lipids, and a high concentration of glutamate/glutamine compounds in meningiomas. A high glutathione (GSH) peak on MR spectroscopy is described.30

Angiography was one of the main investigations performed in the pre-CT/MRI era, with characteristic features of peripherally located lesions with associated mass effect and tumor blush due to vascular supply of the core of the tumor by the dural vessels. However, in the modern era of readily available MRI or at least CT scans, no specific indication or reason was found for performing angiography in more recent series. The need for embolization for pediatric meningiomas is also limited due to the risk of morbidity and availability of modern surgical care.3

PATHOLOGY

Significant macroscopic features of pediatric menigiomas include high number of cystic tumors and large size of these tumors at presentation,1,7,8,10 as discussed earlier. Histopathologically there seems to be higher representation of atypical and malignant (WHO grades II and III) among these tumors.9,28

Meningiomas are currently divided into three grades according to the WHO 2007 classification.31 The majority of these tumors are grade I and considered benign (menigothelial, psammomatous, transitional, fibrous, etc.). The atypical grade tumors are chordoid, clear cell, and atypical; and grade III tumors are rhabdoid, anaplastic, and papillary.32 These have been associated with prognostic significance.33

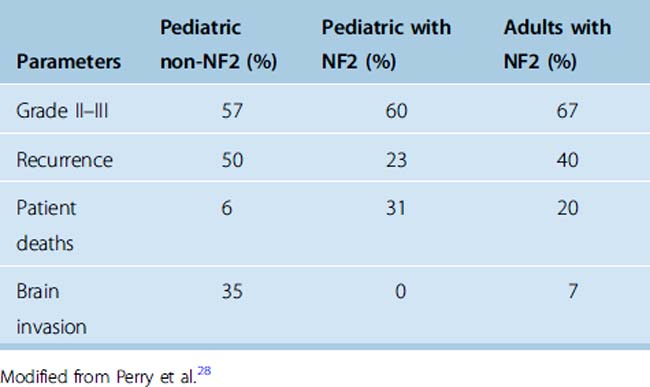

Immunohistochemistry in recent years has been of significant importance in diagnosing these tumors. MIB-1 is an anti-Ki67 monoclonal antibody that is immunoreactive for the nuclei of cells in non-G0 phases.34 The ratio of MIB-1–positive cells (MIB-1 index) is reported to correlate well with histologic grading. A high immunohistochemical proliferation index is found to be associated with increased risk of recurrence.35 Sandberg and colleagues35 studied 14 pediatric tumors and found an MIB-1 index of 12.3% (range 7%–31.6%) in atypical and malignant and 7% (range 1.2%–12.6%) for grade I meningiomas. When patients with NF2 or history of radiation were excluded, the difference between the MIB-1 index medians for benign and atypical/malignant tumors was even more significant (median of 8.4% vs. 25.7%). The authors concluded that the elevated MIB-1 index correlated well with atypia and more aggressive behavior of pediatric meningiomas. Im and colleagues7 observed high MIB-1 (>5%) in 3 of 11 cases, and noted a recurrence after 2 years in 1 case with transitional meningioma and MIB-1 of 10%. They also noted a direct correlation of higher MIB-1 and size of the tumor (5–9 cm), while all were grade I tumors with different histologic subtypes. Perry and colleagues28 also studied in detail 19 pediatric patients with sporadically occurring meningiomas and 14 children and 7 adults with NF2-associated meningiomas. The percentages of high-grade (II and III) tumors were 57%, 60%, and 67% in pediatric non-NF2, pediatric NF2, and adults with NF2, respectively. The rate of recurrences was highest in the pediatric non-NF2 patients of 50% versus 23% in pediatric NF2 tumors, and 40% in adults with NF2.

The number of mitotic figures per high-power field (1 HPF = 0.16 mm2) is one of the WHO criteria for grading of menigiomas. According to this criterion, 4 or more mitoses/10 HPFs is consistent with atypical meningiomas and 20 or more is consistent with anaplastic types. The identification of the morphological changes within cells and consequenely accurate diagnosis can be difficult. Recently a mitosis-specific antibody against phosphorylated histone H3 (PHH3) has been developed that makes identification of proliferating cells much more accurate.34

Meningiomas, in particular of the fibroblastic type, may be difficult to differentiate from schawannomas with routine staining, especially when located in the posterior fossa or spinal canal. For this purpose another immunohistochemical stain for Claudin-1, a key structural protein of tight junctions, has been developed that reacts with meningioma cells but has been shown to have no reactivity with schawnnomas.12

The incidence of various histopathological grades of meningiomas in 936 patients was reported as 94.3%, 4.7%, and 1% for benign, atypical, and malignant tumors, respectively (5:21) in one report. In the series reviewed here (see Table 47-1), the percentage of grade I, II, and III was 82%, 9.6%, and 8.4% respectively. These data indicate that the incidence of high-grade tumors is higher in this age group than in adults.

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

As in dealing with most intracranial neoplasms in this age group, the management options include observation, surgery, and/or radiotherapy with adjuvant chemotherapy.36

SURGERY

In management of pediatric meningiomas, all reported series have been based on surgery as the first line of treatment (see Table 47-3). Surgical management of these tumors can be challenging, which in turn affects the long-term outcome in this population.37

Factors complicating surgery include unusual location, large size, and tumor vascularity, as well as patient-related factors due to prolonged surgery and risks of hypothermia and massive blood transfusion.11

Recurrence is reported in many series mostly in association with subtotal resection. Given that these lesions are benign and have been shown to have good prognosis with total resection, complete surgical resection should be attempted while avoiding further neurologic deficit (see Table 47-3).

As the importance of complete resection is realized based on several series, it has been suggested that complete resection should be attempted, even if this is done in two or three stages.2 Some authors also suggest “second look” surgery to avoid radiation and its long-term complication including secondary tumors.8,11 Stage surgery is also an option for patients with a high blood loss.8 In our institution, we take the approach of maximal resection even if this may require further surgery, to avoid radiation and its long-term complications.

Perioperative mortality related specifically to the tumor characteristics includes the size, location, and vascularity of the tumor. In a series of 152 combined cases, 5 perioperative deaths were recorded.10 Three patients died due to hypothalamic injury, brain stem injury, and intraoperative hemorrhage, respectively, and two died of intracranial infection. In their review of literature Liu and colleagues reported perioperative mortality between 0 and 8.3% with a mean mortality of 3.3%.10

Lund-Johanson and colleagues6 reported acute subdural hematoma in the tumor cavity 8 months after removal of a large meningioma. Significant brain edema as a cause of perioperative death has been reported in several series.11 Arivazhagan and colleagues11 suggested preoperative CSF diversion, antiedema measures, and postoperative ventilation as some strategies to avoid this complication.

ADJUVANT TREATMENT: ROLE OF RADIOTHERAPY AND/OR CHEMOTHERAPY

Before considering radiation therapy, potential adverse effects such as secondary tumors, hormonal deficiency, growth retardation, or cognitive impairment, particularly in younger patients, must be weighed against potential benefits.5

Upfront radiation was shown Leibel and colleagues36 to delay recurrent tumors. However, some authors have suggested reoperation as an option for avoiding radiation.11

Several series have reported postoperative radiation/Gamma Knife radiotherapy for residual or recurrent tumors.8–10

Tufan and colleagues8 reported on 11 cases with 4 malignant tumors, 3 of which were irradiated. One patient was alive without recurrence 8 years postoperatively while another died 8 months postoperation with a large recurrence, and the other had 3 recurrences treated with surgery over a 7-year period.

Rochat and colleagues9 reported on 22 pediatric meningiomas in Denmark between 1935 and 1984. Eight children were irradiated, two of whom had partial resection and survived for 18.5 and 39 years. In our series, we did not perform radiotherapy for residual or recurrent tumors.

OUTCOMES

As discussed in the preceding text, the concept of outcomes in pediatric brain tumors is a complex one. As these tumors are uncommon, most of the series reported in the literature have expanded over a long period, as seen in Table 47-1. Most of the patients in the earlier series were seen before the era of CT and MRI and modern microsurgical techniques. This may explain the suggestion of poor prognosis in these patients.1,4,9

Factors found to be associated with recurrence are completeness of resection, tumor location, and the histopathologic grading of the tumor.2,6,8,38,39 In several series in which NF patients were included, the presence of neurofibromatosis was suggested as another factor associated with higher recurrences and death.2,5,9,15 The 10-year recurrence rates reported by Erdicler and colleagues15 in their series of 29 patients were 82% and 33% for total and subtotal resections, respectively. Despite the majority of patients predating the modern era, Mallucci and colleagues2 reported 92% long-term (40 years) survival in the group with complete resection.

Recurrences after total resection have been reported. Amirjamshidi and colleagues3 and Rochat and colleagues9 reported 6 out of 21 and 6 out of 11 recurrences after reported total resection, respectively. Lack of optimal postoperative imaging to accurately assess the degree of resection and accuracy of histopathologic diagnosis at the time may have contributed to these findings.

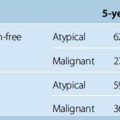

A higher proliferation index (MIB-1) is also associated with higher recurrence.7 Perry and colleagues28 correlated the grading of the meningiomas with rates of recurrences and deaths. These results, as well as death rate and incidences of brain invasion that were considered equivalent to grade II, are represented in Table 47-5. Despite higher recurrences, there were significantly fewer deaths due to tumor recurrence in pediatric non-NF2 patients. Given that five pediatric NF2 patients were diagnosed during the course of the study, the authors recommended that any child with meningioma be carefully examined and followed up because this could be the initial presentation of NF2.

Interestingly, in their series Arivazhagan and colleagues11 reported three cases of progression to a higher histologic grade. These were found on examination of the specimen obtained during surgery of three recurrent tumors that were compared with the original diagnosis.

[1] Drake J.M., Hoffman H.J. Meningiomas in children. In: Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press; 1991:145-152.

[2] Mallucci C.L., Parkes S.E., Barber P., et al. Paediatric meningeal tumours. Child Nerv Syst. 1996;12:582-589.

[3] Amirjamshidi A., Mehrazin M., Abbassioun K. Meningiomas of the central nervous system occurring below the age of 17: report of 24 cases not associated with neurofibromatosis and review of literature. Child Nerv Syst. 2000;16:406-416.

[4] Choux M., Lena G., Genitori L., et al. Schmideck H.H., Sweet W.H., editors. Meningiomas in children. 1991;93-102.

[5] Baumgartner J.E., Sorenson J.M. Meningioma in the pediatric population. J Neuro-Oncol. 1996;29:223-228.

[6] Lund-Johansen M., Scheie D., Muller T., et al. Neurosurgical treatment of meningiomas in children and young adults. Child Nerv Syst. 2001;17:719-723.

[7] Im S.H., Wang K.C., Kim D.G., et al. Childhood meningioma: unusual location, atypical radiological findings, and favorable treatment outcome. Child Nerv Syst. 2001;17:656-662.

[8] Tufan K., Dogulu F., Kurt G., et al. Intracranial meningiomas of childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2005;41:1-7.

[9] Rochat P., Johannesen H.H., Gjerris F. Long-term follow up of children with meningiomas in Denmark: 1935 to 1984. J Neurosurg (Pediatrics 2). 2004;100:179-182.

[10] Liu Y., Li F., Zhu S., et al. Clinical features and treatment of meningiomas in children: report of 12 cases and literature review. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2008;44:112-117.

[11] Arivazhagan A., Indira Devi B., Kolluri S.V.R., et al. Pediatric intracranial meningiomas: do they differ from their counterparts in adults? Pediatr Neurosurg. 2008;44:43-48.

[12] Rosemberg S., Fujiwara D. Epidemiology of pediatric tumors of the nervous system according to the WHO 2000 classification: a report of 1,195 cases from a single institution. Child Nerv Syst. 2005;21:940-944.

[13] Rickert C.H., Paulus W. Epidemiology of central nervous system tumors in childhood and adolescence based on the new WHO classification. Child Nerv Syst. 2001;17:503-511.

[14] Mehrazin M., Yavari P. Morphological pattern and frequency of intracranial tumors in children. Child Nerv Syst. 2007;23:157-162.

[15] Erdincler P., Lena G., Sarioglu A.C., et al. Intracranial meningiomas in children: review of 29 cases. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:136-141.

[16] Herz D.A., Shapiro K., Shulman K. Intracranial meningiomas of infancy, childhood and adolescence. Child Brain. 1980;7:43-56.

[17] Moores L.E., Cogen P.H. Intracranial meningioma. Tumors of the Pediatric Central Nervous System. New York: Thieme, 2001.

[18] Rutten I., Raket D., Francotte N., et al. Contribution of NMR spectroscopy to the differential diagnosis of a recurrent cranial mass 7 years after irradiation for a pediatric ependymoma. Child Nerv Syst. 2006;22:1475-1478.

[19] Schlehofer B., Blettner M., Becker N., et al. Medical risk factors and the development of brain tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:2541-2547.

[20] Modan B., Mart H., Baidatz D., et al. Radiation-induced head and neck tumors. Lancet. 1974;1:227-279.

[21] Osborn A.G. Diagnostic Neuroradiology: A Text/Atlas. St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby, 1994.

[22] Bhattacharjee M.B., Armstrong D.D., Vogel H., Cooley L.D. Cytogenetic analysis of 120 primary pediatric brain tumors and literature review. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1997;97:39-53.

[23] Merten D.F., Gooding C.A., Newton T.H., Malamud N. Meningiomas of childhood and adolescence. J Pediatr. 1974;84:696-700.

[24] Deen H.G.Jr, Scheithauer B.W., Ebersold M.J. Clinical and pathological study of meningiomas of the first two decade of life. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:317-322.

[25] Katayama Y., Tsubokawa T., Yoshida K. Cystic meningiomas in infancy. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:43-48.

[26] Sano K., Wakai S., Ochiai C., Takakura K. Characteristics of intracranial meningiomas in childhood. Child Brain. 1981;8:98-106.

[27] Doty J.R., Schut L., Bruce D.A., Sutton L.N. Intracranial meningiomas of childhood and adolescence. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 1987;30:247-254.

[28] Perry A., Giannini C., Raghavan R., et al. Aggressive phenotypic and genotypic features in pediatric and NF2-associated meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 53 cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;10:994-1003.

[29] Artico M., Ferrante L., Cervoni L., et al. Pediatric cystic meningioma: report of three cases. Child Nerv Syst. 1995;11:137-140.

[30] Optad K.S., Provencher S.W., Bell B.A., et al. Detection of elevated glutathione in meningiomas by quantitative in vivo 1H MRS. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:632-637.

[31] Louis D.N., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O.D., Cavenee W.K. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Nervous System. Lyon: IARC Press, 2007.

[32] Darling C.F., Byrd S.E., Reyes-Mugica M., et al. MR of pediatric intracranial meningiomas. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:435-444.

[33] Glaholm J., Bloom H.J.G., Crow J.H. The role of radiotherapy in the management of intracranial meningioma: The Royal Marsden Hospital experience with 186 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1990;18:755-761.

[34] Takei H., Bhattacharjee M.B., Rivera A., et al. New immunohistochemical markers in the evaluation of central nervous system tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:234-241.

[35] Sandberg D., Edgar M.A., Resch L., et al. MIB-1 staining index of pediatric meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:590-597.

[36] Leibel S.A., Wara W.M., Sheline G.E., et al. The treatment of meningiomas in childhood. Cancer. 1976;37:2709-2712.

[37] Stafford S.L., Perry A., Suman V.J., et al. Primarily resected meningiomas: outcome and prognostic factors in 581 Mayo Clinic patients, 1978–1988. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:936-942.

[38] Jaaskelainen J., Haltia M., Servo A. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: surgery, radiotherapy and outcome. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:233-242.

[39] Chan R.C., Thompon G.B. Intracranial meningiomas in childhood. Surg Neurol. 1984;21:319-322.