50 Pediatric Anesthesia in Developing Countries

THE POPULATION IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD CONTINUES TO GROW while world demographics trend toward an aging population in an urbanized, developed world. Children, many orphaned by the ravages of war, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection,1 and famine, constitute more than one half of the population in many of these countries.2 Eighty-five percent of them will require surgery before their 15th birthday.3 The burden of surgical disease requires safe anesthesia,4,5 but provision of safe pediatric anesthesia6 and intensive care7–9 in the developing world presents serious challenges.10–12 Poverty, poor educational standards, and limited health resources characterize the developing world.5,6,13 Debt repayment, housing, education, social service, and health care provision are near-impossible tasks for most governments of these countries. Of the world’s poorest countries, 70% are in sub-Saharan Africa, and they are ravaged by HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis and are desperately short of health care providers.4,5

Pediatric anesthesia in these low-income countries has not kept pace with the advances made in the developed countries.4 International standards for the safe practice of anesthesia, adopted by the World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WFSA) in 1992, are seldom met in developing countries.14–16 In one survey, only 13% of anesthesiologists were able to provide safe anesthesia for children.3 Consequently, perioperative mortality and morbidity rates in these countries are high by developed world standards5,17–21 although local expectations are commensurate with the facilities and quality of the available care.

This chapter outlines some of the many challenges that anesthesiologists face when providing anesthesia for children in a developing country. Different countries have different problems requiring different solutions. The problems faced in many tropical countries,8,13 for example, are completely different from those on a tropical island in the South Pacific22 or West Indies,23,24 at altitude in Nepal25 and Afghanistan,26 or in the humidity of sub-Saharan Africa.2,3,19,21,27–30 These diverse situations necessitate that generalizations be made. The main differences among the sites, however, are related to the personnel, the spectrum and nature of the pathology, the facilities and equipment available, and a tenuous supply of cheap, generic, and perhaps outmoded drugs.10,31

The Child

Children of the developing world are for the most part victims of circumstance; natural disasters, war, social unrest,32 and economic crises. For many, medical care or timely access to care is a remote or nonexistent possibility.10,25,30,33,34 Fear, poor understanding, and poor education often result in delayed presentation. Frequently, prior visits to well-meaning traditional healers expose the child to additional risks caused by potions that may be hepatic-renal toxic or enemas that may perforate the bowel.35 Further delays occur when patients have to undertake long journeys to the hospital, and if the initial diagnosis is wrong, tertiary referral is made only when complications arise (Fig. 50-1).10,30,36,37

A typical example is acute appendicitis, a relatively uncommon condition in the developing world, where many other causes for a change in bowel habit are initially suspected.37,38 Most patients present for surgery with generalized peritonitis, and perforation is common. In the developing world, the prospect of providing anesthesia for a toxic, acidotic, and dehydrated child is daunting.

Another example is infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, also uncommon in developing countries, where symptoms other than the classic triad of bile-free vomiting, visible peristalsis, and a palpable tumor are more likely. The unsuspecting anesthesiologist, who may have no access to a laboratory2,13–15 and is limited in the choice of fluid for resuscitation, would be challenged to manage the extreme metabolic derangements in these infants.

Superstition plays a role in compounding the anesthesia risk. For example, rural Vietnamese believe that it is not good to die with an empty stomach. Parents consider surgery to be an enormous risk so they feed their children beforehand. In these circumstances, passage of a nasogastric tube before induction is routine, although it is quite likely that the stomach cannot be completely emptied of solids despite the tube.24

Perinatal mortality in some parts of the developing world is ten times greater than those in developed countries.5,39–41 The common denominators are early childbearing, poor maternal health, and lack of appropriate and quality medical services. Although lifesaving practices for most infants have been known for decades, one third of pregnant women still have no access to medical services during pregnancy, and almost 50% do not have access to medical services for childbirth.30,34,41 Most parturients give birth at home or in rural health centers,34 where basic neonatal resuscitation equipment is deficient or nonexistent.30 Those who require surgery may need to be transferred, but specialized transport teams rarely exist.

In some hospitals, neonates are not candidates for surgery because “they always die,”42 whereas in others, they undergo surgery without anesthesia23 because “it’s safer” and because some still believe that neonates do not feel pain. When surgery is performed on neonates, there are additional challenges, particularly in emergency situations.23 Appropriately sized equipment is lacking,36 and it may be extremely difficult to maintain normothermia even in relatively warm climates without improvisation. Regional anesthesia can play a significant role in neonatal anesthesia30,36,43 and in some centers may be the only choice for anesthesia.34,44 Apart from providing analgesia without respiratory depression, the need for postoperative ventilatory support for conditions such as esophageal atresia,45 congenital diaphragmatic hernia,46 and abdominal wall defects is reduced by continuous epidural analgesia (Fig. 50-2).

Regrettably, even neonates who have skillful anesthesia and surgery may die because of inadequate postoperative care.44 Overwhelming infection, sepsis, respiratory insufficiency, and surgical complications are the main causes of morbidity and mortality.30,34 The development of highly specialized neonatal anesthesia and surgical services,7,40–42 essential for a good outcome after neonatal surgery,30,34,36 is a low priority.

Although the burden of disease is dominated by infections and malnutrition,4,5 pediatric trauma has a low level of advocacy and is given scant attention.30,36,47 Socioeconomic advances in some countries have introduced a new danger in the form of faster, more powerful vehicles without the necessary maintenance culture or road discipline. Road traffic accidents are inevitable, and effective systems to handle the polytrauma victims that result are hard to find.36

Road traffic accidents are common. Even simple bone fractures have disastrous outcomes. Inappropriate management by traditional bonesetters frequently results in compartment syndromes or gangrene.47 Trauma prevention strategies are given low priority despite the acknowledged impact trauma has on the economy of any country. Many developing countries are at war, and this has led to massive trauma and injuries to children who are participants in the fighting or innocent bystanders.

Children and War

Children may be victims of all aspects of violence. They face an intense struggle for survival as a consequence of displacement, separation from or loss of parents, poverty, hunger, and disease. They are vulnerable to the abuse of abandonment, abduction, rape, and forced soldiering. An estimated 300,000 children are used as child soldiers in more than 30 countries.48 Many sustain physical injuries and permanent disabilities, and a large number acquire sexually transmitted disease, including HIV infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). These HIV-positive child soldiers then become vectors in communities where they are deployed.49

For many of these children, acts of violence become their form of normality, and the former victims become the perpetrators.32 Survivors are subjected to the total collapse of economic, health, social, and educational infrastructures. Lost and abandoned children sleep on the streets and are forced to beg for food while trying to find their families. Many become child laborers or turn to crime or prostitution for survival.50

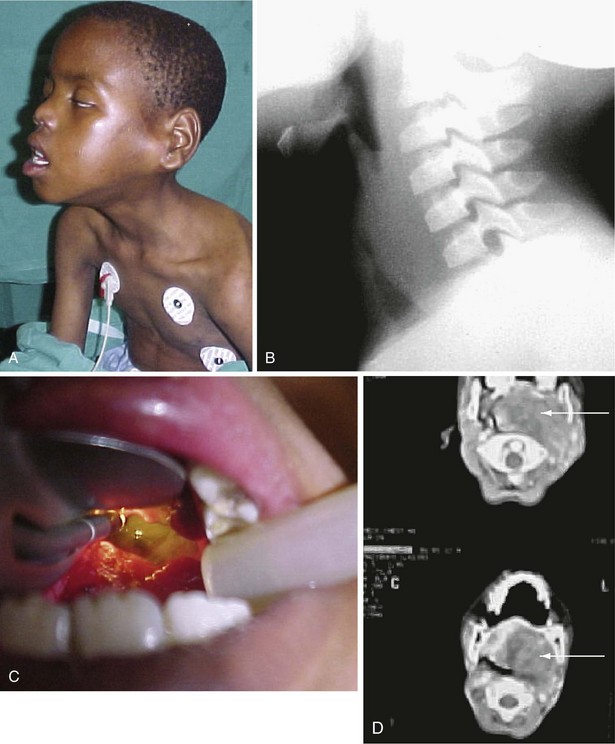

Children in war-torn areas sustain bullet, machete, or shrapnel wounds, and others are burned. They often sustain mutilating injuries (Figs. 50-3 and 50-4) that are not commonly seen in civilians.51 Land mines are responsible for killing or maiming an estimated 12,000 civilians per annum. In Angola, a country with the highest rate of amputees in the world, there were an estimated 5.5 land mines for every child. Continuing land mine explosions remain a legacy of this conflict.51 These blast injuries leave children without feet or lower limbs and with genital injuries, blindness, and deafness—a pattern of injury that has become a post–civil war syndrome encountered by surgeons worldwide.51 Although the war in Angola is essentially over, the cost of mine removal is beyond the means of local governments. Ironically, artificial limb manufacture has become a developing industry.51 Tragedies such as these are likely to be repeated in the ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Somalia.

Pain

Pain management modalities for children in a First World environment are vastly different from those available to practitioners working with limited resources.52 Attempting to apply similar standards is fraught with difficulty. Illiteracy, malnutrition, poor cognitive development, different coping strategies, altitude (e.g., chronic hypoxia),53 and pharmacogenetic, cultural, and language differences all contribute to the complexity of the problem.54

Children of the developing world learn to cope with vastly different problems. They may be victims of poverty, malnutrition, violence (e.g., war, trauma, abuse), and their attitudes about pain and pain tolerance are diverse. Children from an impoverished background seem more stoic and indifferent to even severe pain. After cardiac surgery, for example, some appear to need very little pain relief and are easily soothed by lollipops (A. Davis, personal communication) or play therapy.33 Many walk from the intensive care unit to the general ward on the first postoperative day (A. Davis and R. Ing, personal communication).

Pain assessment of children from an impoverished background is difficult55 (see Fig. 50-3, B). Many children in acute pain do not show facial expressions. Is this stoicism or simply a reflection of malnutrition, lack of social stimulation, severity of illness, or even cultural attitude? Language difficulties, cultural barriers, willingness to share information, emotional expressiveness, and outdated attitudes of the caregiver may endorse this quandary. Some societies convey pain readily, but others teach that expression of pain is inappropriate. Although many pain assessment instruments are available, few have been validated in the developing world.55–57

Human Resources

Anesthesia does not enjoy a high profile and lacks the voice to demand access to resources in developing countries. The critical shortage of manpower is a barrier to progress.5,8 Anesthesia is frequently delivered by nonphysicians,3,6,58 a reality that has remained constant over many decades. Most anesthetics are administered by nurses or unqualified personnel who have little medical background and are “trained on the job.”3,36 In many African5,59 and Asian countries,5,60 the ratio of doctors to patients often is so small that the ideal of employing a physician specifically to provide routine anesthesia is out of the question.5,61,62 Salaries are insufficient to attract suitably trained and qualified practitioners for more than short periods. Emigration of scarce trained personnel to developed countries in search of better salaries and improved lifestyles exacerbates these human resource difficulties.3,5,10,58,61–64

Anesthesia is not perceived as an attractive career for many undergraduates,63 who receive little or no exposure to the specialty.64 In some countries, surgery is performed without the “luxury” of anesthesia.65 Few developing countries can afford specialist anesthesiologists, except possibly in the principal hospitals. Supervision of “nonphysician anesthesiologists” is invariably inadequate,66 and access to textbooks, journals, or other medical literature is limited. Internet access depends on a reliable electrical supply, telecommunications network, and a computer, luxuries that are considered the norm in the developed world.67,68

On a more positive note, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized that surgery is a public health issue and has launched the Safe Surgery Saves Lives program.5,16,17,62,69 The WHO has emphasized that safe surgery does not exist without safe anesthesia.10,11,16,17 Training anesthesiologists in the skills required for pediatric anesthesia is a slow process. It is hoped that the WFSA program69–78 will snowball so that children undergoing surgery in developing countries will reap the benefit.

Pathology

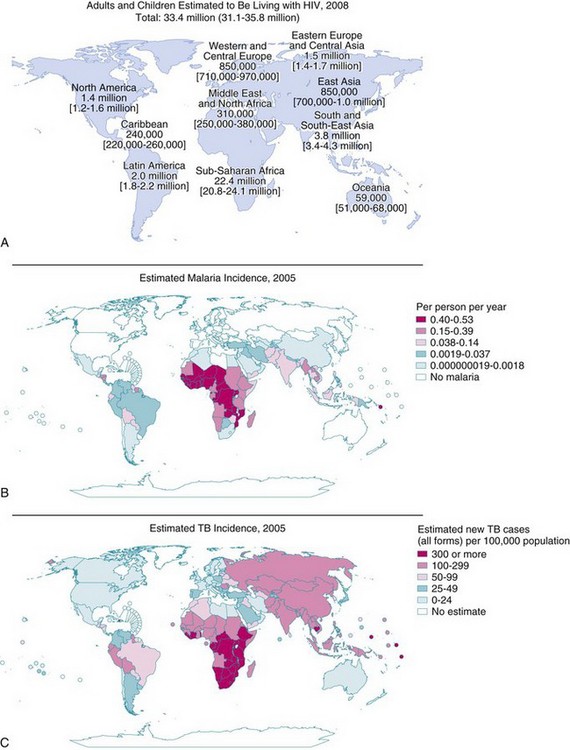

Many pathologic conditions that are seldom seen in industrialized countries are more prevalent in developing countries because of poor health education, malnutrition, proximity of livestock to humans, earth-floored homes, poor sanitation, and contaminated water supplies (Fig. 50-5). Some conditions that are prevalent worldwide and relevant to the anesthesiologist are considered in the following sections.

(A, From AIDS Epidemic Update, p. 66. Available at http://data.unaids.org/pub/EpiReport/2006/2006_EpiUpdate_en.pdf, page 66 [accessed July 2012]; B, from World Malaria Report. Available at http://www.rbm.who.int/wmr2005/html/map3.htm [accessed July 2012]; C, from World Health Report, 2006. Available at http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/ [accessed July 2012].)

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

An estimated 33.4 million people are living with HIV. Most cases occur in the developing world (90%), with sub-Saharan Africa (22.4 million) and Southeast Asia (3.8 million) making up two thirds of the global total; approximately 6% are children (see Fig. 50-5, A).79 More than 25 million have died of HIV-related diseases since 1981, and as a consequence, there are an estimated 14 million orphans in sub-Saharan Africa alone.79 Worldwide, more than 1000 children are newly infected with HIV each day; most of these children are in sub-Saharan Africa.80 The prevalence of HIV seropositivity varies from one country to another. In this environment, it is prudent for the anesthesiologist and surgeon81 to assume a positive status for every patient until proved otherwise.36

Although some success has been achieved in slowing the transmission of HIV in developed countries,81–87 there are numerous barriers to the treatment of HIV-infected children in the developing world. Only 4 million people in low- to middle-income countries have access to treatment.79 Treatment of children has lagged behind that of adults, in part because of the expense and the lack of pediatric antiretroviral drug formulations84 but mainly due to poor human resources and infrastructure for administration of treatment.88 Only an estimated 38% children infected with HIV receive treatment.79

Children can be infected by vertical transmission from the mother (>90%) or when sexually abused (≈2%) by an infected adult.89 Transmission through blood products remains a risk, but with the global trend toward volunteer donors and more sophisticated testing of blood, this risk is expected to diminish. Vertical transmission can occur in utero, during labor and delivery, or postnatally. Risk factors include maternal plasma viral load and breastfeeding.80,86 Data indicate that mixed feeding (i.e., breastfeeding with other oral foods and liquids) is associated with the greatest risk of transmission.90 Perinatal transmission rates have been dramatically reduced by universal HIV testing of pregnant women, provision of antiretroviral therapy (when needed for maternal health) or prophylaxis, elective cesarean delivery, and avoidance of breastfeeding.80,86 Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the triple antiretroviral therapy, has changed HIV from a fatal illness to a chronic disease with decreased mortality rates and improved quality of life86; however, these strategies require resources.

Progression of the disease depends on the mode of transmission; vertically acquired infection is more aggressive than other forms. Between 20% and 30% of untreated HIV-infected children will develop profound immunodeficiency and AIDS-defining illnesses within a year, whereas two thirds will have a slowly progressive disease. The course of the disease depends on a variety of factors, including timing of infection in utero, the viral load, the mother’s stage of the disease, and whether the mother is receiving antiretroviral therapy. Treatment of children depends on clinical category, CD4 T-cell cell count, viral load, and age at the time of diagnosis. According to the current state of knowledge, after HAART is started, it must be carried on lifelong. This implies great challenges in adherence to avoid development of resistance and to evade long-term adverse effects of HIV therapy. Emerging drug resistance in children in low- and middle-income countries has necessitated new treatment strategies.84,87

The clinical manifestation of HIV in infants and children depends on whether they have been managed with antiretrovirals.81,84,87 Most have asymptomatic infections, and the presentation may be subtle, such as failure to thrive, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, interstitial pneumonia, chronic diarrhea, or persistent oral thrush. Some present for the first time with life-threatening disease. Chronic diarrhea, wasting, and severe malnutrition predominate in Africa, whereas systemic and pulmonary pathologies are more common in the United States and Europe. Recurrent bacterial infections, chronic parotid swelling, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis (LIP), and early onset of progressive neurologic deterioration are characteristic of children with AIDS.

Pulmonary disease remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality.91–93 Bacterial pneumonia, viral pneumonia, and pulmonary tuberculosis are common in children throughout the developing world. The course of these infections is more fulminant when associated with HIV infection.94 Acute opportunistic infections occur when the CD4 T-cell count falls; they include Pneumocystis (carinii) jiroveci pneumonia (PCP or PJP), cytomegalovirus infection, and the more typical Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and respiratory syncytial virus infections.91,92,94 The classic presentation of PCP is fever, tachypnea, dyspnea, and marked hypoxemia, but in some children, the presentation is more indolent, with hypoxemia preceding clinical or radiologic changes.95

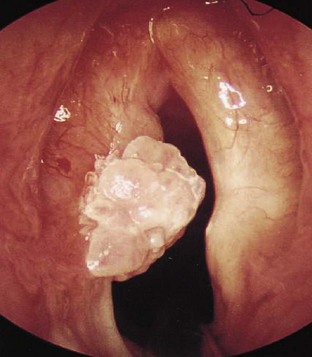

LIP is a slowly progressive, chronic form of lung disease seen in older children. It can lead to an insidious onset of dyspnea, cough, and chronic hypoxia with normal auscultatory findings and can cause pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia in AIDS patients. In contrast to adults, LIP in children may cause acute respiratory failure, which is treated with steroids and bronchodilators. The clinical manifestations affecting otolaryngologists96 and dental surgeons97 have been outlined. Management of the upper airway may be difficult in the presence of stomatitis and gingival disease. Intubation may be difficult in the presence of acute (i.e., candidal infection) or chronic epiglottitis (i.e., lymphoid hyperplasia), necrotizing laryngotracheitis, Kaposi sarcoma (Fig. 50-6), or laryngeal papillomas (Fig. 50-7). These comorbid respiratory disorders can challenge even the most experienced pediatric anesthesiologist (Fig. 50-8).

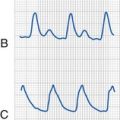

Cardiac disease is being recognized with increasing frequency in HIV-infected children. The pathogenesis of cardiomyopathy is multifactorial and includes pulmonary insufficiency, anemia, nutritional deficiencies, specific viral infections, and drug therapy. Left and right ventricular dysfunction, arrhythmias, and pericardial effusions occur, but pulmonary hypertension is rare.98 HIV may directly infect the myocardium, leading to early electrocardiographic (ECG) changes and abnormal echocardiograms showing hyperdynamic left ventricular dysfunction or evidence of diminished contractility (e.g., dilated cardiomyopathy, myocarditis).

The gastrointestinal tract is commonly involved,99 particularly in those living in tropical countries, and affected children show evidence of malabsorption (i.e., slim), chronic recurrent diarrhea, dysphagia, failure to thrive, or enteric infection. They may require endoscopy for diagnostic studies. From the point of view of the anesthesiologist, there is an increased risk of reflux due to esophagitis, which may be caused by infection (e.g., Candida, cytomegalovirus) or drugs (e.g., zidovudine). Pseudobulbar palsy, a manifestation of central neurologic involvement, or esophageal strictures may occur.

Medications used to manage HIV are involved in drug interactions on several levels.100 The reverse transcriptase inhibitors (e.g., zidovudine) are excreted by the kidney, and drugs affecting renal clearance reduce excretion. Reverse transcriptase inhibitors may induce CYP3A4 (e.g., nevirapine) or inhibit CYP3A4 (e.g., delavirdine) and affect other drugs (e.g., midazolam, levobupivacaine, ketamine, methadone) cleared by this enzyme. Protease inhibitors are inhibitors of CYP3A enzyme systems and are substrates and inhibitors of P-glycoprotein transporters. Coagulation status with the concomitant use of warfarin (which is metabolized by CYP2C9) may be altered by enzyme induction (e.g., ritonavir) or competition for clearance pathways (e.g., efavirenz, nelfinavir).101

Protease inhibitors also can inhibit specific uridine 5-diphosphoglucuronosyltransferase (UGT) pathways. This accounts for the increase in bilirubin concentration (i.e., UGT1A1 glucuronidates bilirubin) observed in some patients. UGT1A6 (i.e., acetaminophen glucuronidation) and UGT2B7 (i.e., morphine glucuronidation) are unaffected.102 Gastric motility changes due to opioids (e.g., methadone) reduces absorption of some reverse transcriptase inhibitors.

HIV, a neurotrophic virus, can have a devastating effect on the immature brain, which is further compounded by the opportunistic infections and neoplasms that occur as a consequence of the associated immunosuppression.103 Neurologic impairment is seen in most symptomatic HIV-infected children, commonly as a progressive encephalopathy with developmental delay, progressive motor dysfunction, and behavioral changes. Craniofacial dysmorphic features have been described. Hematologic abnormalities can reflect depression of all cell lines. Anemia may be caused by primary marrow failure, malnutrition, or drugs, whereas thrombocytopenia may reflect an autoimmune disorder.

Universal precautions should be strictly applied for all anesthesia procedures. Extra care should be taken when anesthetizing an HIV-infected child. Precautions should also be taken to prevent contamination of the anesthetic circuits. Disposable equipment, bacterial filters, and disposable circuits are recommended. The prohibitive cost for most institutions in developing countries limits the use of disposables. Reusable equipment should be cleaned, sterilized, and decontaminated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fortunately, HIV is sensitive to a wide range of disinfectants.104

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality.36,105–110 The epidemiology of pediatric tuberculosis is shaped by risk factors such as age, race, immigration, poverty, overcrowding, and prevalence of HIV/AIDS (see Fig. 50-5, C).109,110 HIV and tuberculosis form a dangerous synergy that is difficult to manage in view of drug interactions between the antituberculosis and antiretroviral agents.79,106 Even bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccinations can cause significant complications in immunocompromised HIV patients.106 The emergence of drug-resistant tuberculosis adds to the burden and is a constant danger to health care workers in general and anesthesiologists in particular.

Primary tuberculosis infection usually does not produce clinical illness in well-nourished, immunized children, whereas reactivated pulmonary tuberculosis is a chronic or subacute disease that may present a variety of challenges for the anesthesiologist, including preventing transmission by contamination of the anesthetic circuits and the risks associated with pleural effusions, pulmonary cavitation, or bronchiectasis.93,95 Mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy may severely compromise the airway.

Primary tuberculosis and its complications are more common in children than in adults. After young children are infected, they are at increased risk for progression to extrapulmonary disease.109,110 Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection can cause symptomatic disease in any organ of the body and is usually a reactivation of a latent site of infection. The most common sites of reactivation are lymph nodes, bones, joints, and the genitourinary tract. Less frequently, the disease may involve the gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, pericardium, or skin. Tuberculosis meningitis and miliary tuberculosis, both more common in children, carry a high mortality rate.109 In view of the high prevalence of HIV infection among tuberculous children, HIV testing should be performed on all children with tuberculosis; conversely, tuberculosis should be sought in all HIV-positive children. Tuberculosis is, however, difficult to diagnose in young children, and the search for more sensitive tests continues.105

Malaria

Malaria (see Fig. 50-5, B) is a febrile, flulike illness caused by one of four species of malaria parasites: Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae. Effective and safe prophylaxis against malaria has become increasingly difficult because the species that causes the most severe illness, P. falciparum, has become widely resistant to chloroquine and to other antimalarial drugs in some areas.110 Severe malaria, even when optimally treated, carries a mortality rate of 10% to 25%.110–112

Prompt diagnosis and early treatment is an important determinant of outcome. Uncomplicated malaria usually manifests as fever, headache, dizziness, and arthralgia. Gastrointestinal symptoms may predominate and include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort or pain that may mimic appendicitis. In children, malaria can manifest with an acute, life-threatening disease or run a chronic course with acute exacerbations. The acute manifestations include three overlapping syndromes: respiratory distress due to a severe underlying metabolic acidosis (pH <7.3), usually a lactic acidemia; severe anemia (hemoglobin <5 g/dL) with hypovolemia113 and thrombocytopenia; or neurologic impairment as a manifestation of cerebral malaria.111–114 Seizures are an important presenting feature in 60% to 80% of cases. Prolonged seizures refractory to treatment and those that occur on antimalarial treatment are ominous signs and are usually associated with neurologic sequelae or death.113 Cerebral malaria can also manifest as a prolonged postictal state, status epilepticus, severe metabolic derangement (i.e., hypoglycemia and metabolic acidosis), or a primary neurologic syndrome, ranging from diffuse cortical involvement to brainstem abnormalities.

Although controversial, exchange transfusion has been advocated for severe malaria, particularly for those with cardiorespiratory compromise, hyperparasitemia, or cerebral malaria. The rationale is to remove harmful metabolites, toxins, and cytokines; decrease the parasite load; remove deformed red cells; and restore normal red cell mass, platelets, and other clotting factors.113 Unfortunately, many malaria-endemic areas also have a high prevalence of HIV, adding significantly to the risk of blood transfusions.

Cardiac Disease

Pediatric cardiac services typically are too expensive for most developing countries, and the increasing economic divide threatens those services that do exist.115,116 In North America, each cardiac center serves 120,000 people; by contrast, one center serves 16 million people in Asia and 33 million in Africa.61 Despite the need, few third world units can treat the required volume of cases. Unless families have the financial means to travel to a developed country, the options for diagnostic or therapeutic cardiac procedures are poor.33,115–117 Medical missions may provide immediate help, but their impact on a developing country is short term and potentially disruptive. These visiting teams ultimately have little effect on the complex socioeconomic and sociopolitical problems that exist.116

Rheumatic heart disease is more common than congenital heart disease in many developing countries,115–117 reflecting the socioeconomic problems of poverty, overcrowding, malnutrition, and lack of antibiotics. Children often present late with life-threatening symptoms due to repeated infections and superimposed endocarditis. The acute deterioration precipitated by endocarditis may be the factor that prompts the search for medical attention. Valve replacement can be lifesaving, but long-term follow-up of anticoagulant therapy is often not feasible.

Congenital heart disease is an additional challenge, and it is common to see congenital heart defects in adults in developing countries. Those who have survived without the benefit of palliative or corrective surgery may present with pulmonary hypertension or endocarditis. Total correction of these defects usually is not feasible, and palliative surgery may be the more effective alternative. Excellent palliation with reasonable quality of life can be achieved relatively cheaply.116

Tetanus

Tetanus is a disease characterized by painful tonic muscle spasms, hyperreflexia, and autonomic instability.118 It is caused by the exotoxin of Clostridium tetani, an organism that is ever present in the soil and contaminated wounds. Although rarely seen in developed countries, tetanus is prevalent in countries where children are not routinely immunized. Tetanus neonatorum carries a high mortality rate and is still encountered in areas where it is customary to apply feces to the umbilical cord to stop bleeding.

Trismus is the presenting sign in most cases, and sustained trismus produces a characteristic sardonic smile (i.e., risus sardonicus). Persistent contractions of the chest and back muscles result in opisthotonos. Restlessness and irritability may be followed by tetanic seizures, which are often precipitated by trivial stimuli (e.g., touch, noise). Glottic or laryngeal spasm can cause sudden death. Late deaths may be caused by nosocomial infection, renal failure, sudden cardiac arrest, or cerebral hemorrhage as result of the autonomic instability.118

Treatment consists of surgical débridement of the wound, administration of human tetanus immunoglobulin, antibiotic therapy, and intensive supportive medical care. Ventilatory support is invariably necessary because the frequent spasms impair ventilation already compromised by sedative therapy. Benzodiazepines and opioids are the mainstay of treatment, but numerous protocols have been studied.118 Magnesium sulfate has been successfully used to reduce spasms and has been shown to reduce circulating catecholamines,119 whereas clonidine does not.120 Pain management should also be considered, and I have been encouraged by the use of continuous epidural analgesia for these children. Further advantages of epidural analgesia include good control of autonomic instability, earlier weaning from ventilatory support, and possible reduction in the complication rate.118 From the anesthesiologist’s point of view, trismus is overcome by muscle relaxants and does not pose a significant intubation problem.

Drugs

The supply of anesthetic gases and drugs for rural medical facilities is erratic and unreliable.3,8 The cost of many drugs, particularly the modern anesthetics, has increased alarmingly beyond the reach of most health care budgets. Anesthesiologists in developing countries therefore must be resigned to using less expensive anesthetics or generic medications.

Ether and halothane remain the only inhalational anesthetics available in many countries and are the mainstay of anesthesia in many institutions.2,3,10,31,121 Ether is cheaper and probably safer than halothane, although its use is limited by its flammability. This extreme flammability limits its transportability and therefore its availability in remote areas.

Ether and halothane have virtually disappeared from the operating rooms in the developed world and have been replaced by isoflurane, sevoflurane, and desflurane. As demand for the less-expensive agents has waned, some manufacturers claim a lack of profitability for them and have threatened their withdrawal. Although this may make commercial business sense, these agents sustain the anesthesia services for millions of patients in the developing world,2 and their loss would be tragic.

Ketamine is probably the most commonly used intravenous anesthetic.3,65,121 Ketamine is simple to use, effective, and relatively safe when used as a sole agent for short procedures, used in combination with muscle relaxants, or used to supplement general anesthesia for major surgery. It should be used with midazolam to reduce the hallucinatory side effects and nightmares after ketamine use. Benzodiazepines, however, are not always available. Morphine and other opioids may not be permitted in some cultures or even available in some institutions. It is sobering to realize that only 6% of the morphine consumption worldwide is used in the low- and middle-income countries that are home to 80% of the world’s population.52

The cost of nitrous oxide is prohibitive in terms of storage, erratic delivery, and budgetary constraints.122,123 Closed or semiclosed anesthetic systems are considered dangerous in an environment where the oxygen supply is erratic,123 agent monitors are seldom available,25 and the supply of soda lime and compressed gas cylinders is erratic. Consequently, the potential benefits and cost savings of low-flow anesthesia are lost.123,124

Regional anesthesia has many benefits in terms of safety, cost savings, and immediate postoperative analgesia.* Children in developing countries usually are very accepting of this form of analgesia. However there seems to be a general reluctance to perform regional anesthesia in children,29,36 even in some institutions in the developed world. Possible reasons include lack of training or expertise, fear of failure, and the unavailability of drugs, disposables, and other ancillary equipment such as ultrasound.

Improvisation may be the key. In the absence of appropriate equipment, access to the epidural space can be achieved by using a technique first described before the introduction of pediatric epidural needles into clinical practice. A catheter can be threaded through an intravenous cannula into the epidural space through the sacral hiatus in neonates and small infants.127 Cheap, uninsulated needles can be used for peripheral nerve blocks when more expensive, insulated needles are not available.128

Blood Safety

An estimated 70% of all blood transfusions in Africa are given to children with severe anemia caused by malaria. Blood transfusion services, when they exist, aim to provide a lifesaving service by ensuring an adequate supply of safe blood.129–131 Patients, particularly children, in developing countries face the greatest risks from unsafe blood and blood products.130–133

Less than 30% of developing countries have a nationally coordinated blood transfusion service. Many do not perform the most rudimentary tests for diseases such as HIV or hepatitis B and C because of economic constraints.133 Even limited testing doubles the basic cost of a unit of blood. It is estimated that about 6 million tests that should be done globally to check for infections are not done annually.

Many countries still rely on paid donors or family members to donate blood before surgery.133 In Argentina, for example, up to 92% of the blood supply is derived from family members. Although voluntary, unpaid blood donation has increased to 20% in the past 5 years in Pakistan, family donors comprised 70% and paid donors 10% of the blood donors in 2004.131 Public education about the value of blood transfusion is vital to improve supply.129,130 Through concerted efforts by the World Health Organization to improve blood safety worldwide over the past decade, the number of voluntary, unpaid donors has increased considerably. For example, voluntary blood donation in China increased from 45% of donations in 2000 to 90% in 2004. Similarly, the rate of voluntary, unpaid donations in Bolivia increased from 10% in 2002 to 50% in 2005. Malaysia, China, and India reached 100% screening of donated blood for HIV by the year 2000.132

There are risks in any system.129,130 Family and paid donors may hide aspects of their health and lifestyle that could make the blood unsafe for different reasons. Family members may feel pressured to donate, whereas paid donors are driven by need and avoid important details about their health status that would negate the transaction. The commercial plasma industry and blood trade can fuel the transmission of HIV. In 1999, 26 million liters of plasma were fractionated for global use,133 and the major source was paid donors from developing countries. Voluntary, unpaid donors have a greater sense of responsibility to their community and keep themselves healthy to be able to keep giving safe blood. South Africa has had 100% voluntary, unpaid donations since it established a national blood service. With HIV prevalence approaching 30% among the adult population of Africa, only 0.02% of its regular blood donors in South Africa have contracted HIV.

Storage of blood is difficult considering the unreliable and unpredictable electricity supply in many developing countries. To obviate the risk of transmission of malaria, HIV, and other infectious diseases, blood should be transfused only when absolutely necessary. In sophisticated blood transfusion units, the use of predonated autologous blood is an option.134–135 In poorer countries, this is not practical because malnutrition and chronic anemia are common. There is often a lack of appropriate equipment, and cost is prohibitive. Similarly, intraoperative blood salvage and cell savers appropriate for use in children are not available. Recombinant factor VII, which is being used increasingly to reduce blood use by those who can afford it,134 is beyond the scope (and cost) of practice in many countries.135

Equipment

Electricity is unreliable in many hospitals in the developing world. In some, particularly in rural areas, neither power-line electricity nor a reliable functional generator is available.3,4 General facilities for infection control, such as running water, disinfectants, or gloves, are also unreliable, even though recycling disposable equipment such as endotracheal tubes is considered normal practice in many countries.2

Essential equipment to provide safe anesthesia for children and particularly for neonates is lacking.3,25,30,36 Neonatal or pediatric ventilators are virtually nonexistent outside the main centers.30 Small intravenous cannulae are a precious commodity, and butterfly needles are still used and sometimes reused. Syringe pumps and other control devices are impractical in environments that have an erratic electricity supply. Metal and plastic laryngoscopes usually are available but not well maintained. Batteries may be in short supply and light bulbs unreliable. A full range pediatric tracheal tubes is considered a luxury. Laryngeal mask airways in pediatric sizes are usually unavailable. Intravenous fluids are very expensive if not manufactured locally, and many developing countries do not have local production facilities.10 The choice of intravenous fluid is therefore limited and in short supply.

Monitoring is very basic: a precordial stethoscope and a finger on the pulse.2,11 ECG monitoring is used when available, but it depends on a continuous electricity supply and proper maintenance. Appropriately sized blood pressure cuffs are scarce. Pulse oximetry has been the most useful monitor and should be available in all centers where pediatric surgery is performed.2,25 Unfortunately, this ideal is far from reality, but it is hoped that the global pulse oximetry project will be rewarded with universal quality improvement.17

Simplicity and safety has long been the key to anesthetic equipment in developing countries.2–4136 Ideally, a suitable anesthetic machine should be inexpensive, versatile, robust, and able to withstand extreme climatic conditions; able to function even if the supply of cylinders or electricity is interrupted; easy to understand and operate by those with limited training, economical to use; and easily maintained by locally available skills.136–138 The cheapest, most practical, and most widely used method is inhalational anesthesia administered through an Epstein Macintosh Oxford drawover vaporizer (EMO, Penlon Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom) or Oxford Miniature Vaporizer (OMV, Penlon Ltd.). Oxygen concentrators supplement oxygen delivery and eliminate the need for expensive oxygen cylinders, whose reducing valves are often faulty or destroyed in these situations. The most appropriate ventilator is the Manley Multivent Ventilator, which essentially functions like a mechanical version of the Oxford Inflating Bellows (OIB) and can be used with a drawover system.138

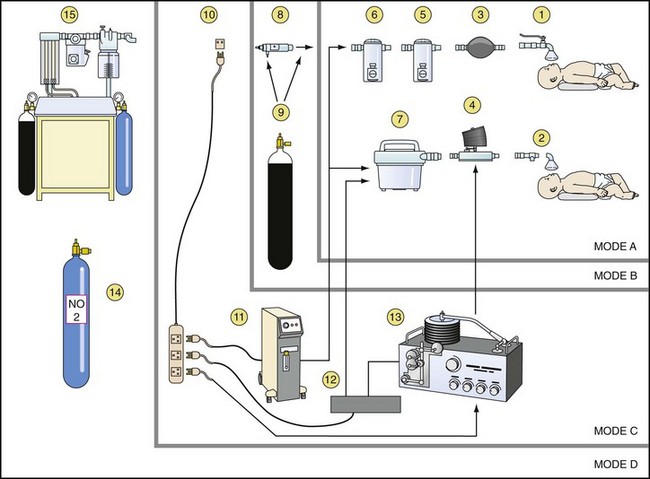

A general scheme for inhalational anesthesia, which was first proposed by Ezi Ashi and colleagues in 1983,124 for use in developing countries is shown in Figure 50-9.136 Applying this scheme, four different modes can be used and modified according to the available supplies and services. The basic mode A is used when there is no electricity and no supply of compressed gases. The apparatus consists of a low-resistance vaporizer linked by valves to the child to act as a drawover system with room air as the carrier gas. The self-inflating bag or hand bellows makes it possible to provide artificial ventilation while the vaporizer remains as a drawover device. The addition of low-flow oxygen to the inspired gas in mode B depends on the availability of an oxygen cylinder. The addition of a length of reservoir tubing to the circuit enables oxygen to be stored on expiration and to be used on the next inspiration, substantially improving its economy.

Drawover Anesthesia

Drawover anesthesia enables inhalational anesthesia to be administered using atmospheric air as the carrier gas. The essential features of this system consist of a calibrated vaporizer with sufficiently low resistance (i.e., EMO and OMV) to allow the negative pressure created by the child’s inspiratory effort to draw room air through the vaporizer during spontaneous ventilation. Positive-pressure ventilation can be provided by means of a self-inflating bag or bellows (OIB), using a valve to prevent the gas mixture from reentering the vaporizer and a unidirectional valve at the child’s airway to direct expired gases to the atmosphere, preventing rebreathing (see mode A, Fig. 50-9). In this way, an anesthetic can be administered in the absence of compressed gases. The vaporizer has an inlet for supplementary oxygen that can be attached to the oxygen output tube of an oxygen concentrator or oxygen cylinder when available (see modes B and C, Fig. 50-9).

The EMO and OMV are the more commonly used low-resistance vaporizers. The EMO is calibrated only for ether, but its performance is linear for other agents. The OMV is calibrated for a variety of agents;42,137–139 despite the lack of temperature compensation, its performance is stable under most conditions. Both vaporizers have been used successfully in pediatric anesthetic practice,33 but it is recommended that they be converted to form a T-piece for greater safety.

The OMV has been evaluated as a simple drawover system for pediatric anesthesia. Wilson and Bem42 showed that when a self-inflation bag is used in a drawover mode, more efficient vaporization occurs despite vaporizer cooling. However, the respiratory efforts of neonates or weak infants are insufficient to operate the valve mechanisms of the self-inflating bag (e.g., Ambu bag), necessitating continuous assisted ventilation even in the presence of ether, which stimulates ventilation.

Oxygen Concentrators

Improved oxygen availability, independent of compressed gas and electrical power supply, can be provided by linking oxygen concentrators140,141 to a drawover anesthetic apparatus as first described by Fenton.121 Maintenance requirements are low, and servicing is recommended only after approximately 10,000 hours of usage. The benefits are enormous, but a reliable electricity supply is critical.

The concentrator functions by using a compressor to pump ambient air alternately through one of two canisters containing a molecular sieve of zeolite granules that reversibly absorbs nitrogen from compressed air.121,136,140 The controls are simple and comprise an on/off switch for the compressor and a flow-control knob to deliver 0 to 5 L/min. Flow of oxygen continues uninterrupted as the canisters are alternated automatically so that oxygen from one canister is available while the other regenerates. A warning light on a built-in oxygen analyzer illuminates if the oxygen concentration is less than 85%, and the concentrator switches off automatically when the oxygen concentration is less than 70%. This action is heralded by visual and audible alarms. Air is then delivered as the effluent gas. Modern machines are relatively silent.

The oxygen output of the concentrator depends on the size of the unit, the inflow of oxygen, the minute volume, and pattern of ventilation. The addition of dead space (or oxygen economizer tube) at the outlet improves the performance, and predictable concentrations of more than 90% oxygen can be obtained with flows between 1 and 5 L/min, independent of the pattern of ventilation. Much lower concentrations and less predictability were observed when the dead space tubing was omitted.142

The Visitor

Personality traits compatible with survival have been suggested as a prerequisite for working in the developing world. These traits include an almost pathologic desire for work, a willingness to merge or at least sympathize with different cultures, patience in relating to and teaching people sometimes far removed educationally, the ability to withstand prolonged periods of cultural isolation, and mostly a never-failing ability to improvise and make the best of a bad situation.143–147 There is no place for risk-taking “cowboy anethesiologists.”139,147

International travel, particularly visits to many parts of the developing world, needs careful preparation and planning, whether the anesthesiologist is part of a volunteer organization33,145–148 or traveling as an individual.146 Detailed advice144–149 is beyond the scope of this chapter, but some generalizations are made based on personal experience and that of colleagues. Changing political climates and international health guidelines dictate visa and vaccination requirements. Expert advice should be sought to tailor the traveler’s needs according to the individual’s medical and immunization history, the duration of stay, and proposed itinerary.

Conclusions

Attracting trained anesthesiologists to work in the developing world is difficult.5,62,70–74,146–150 Temporary sojourns with volunteer medical groups are for the most part stimulating, but volunteers are unlikely to return for longer periods, let alone permanently.

Can anything be done to improve the lot of children who undergo anesthesia in the developing world? The Pediatric Anesthesia Fellowship Program established through the WFSA is commendable, but it produces only a small number of trainees each year.70,73,74 Audits of morbidity and mortality are the first steps toward improvement if action is taken to address the problems uncovered. Publications reflecting outcomes in developing countries have increased over the past decade.19–21 Purchasing equipment without ensuring subsequent maintenance is wasteful. Disposables are short-lived items even if they are recycled. Human resources are needed.

Different standards may emerge from different parts of the world. These standards need not necessarily be considered inferior but may open the way for the assimilation of new ideas.149 The nuances of practice in different communities inevitably vary and may challenge some fondly held beliefs in pediatric anesthesia. A safe anesthetic is not necessarily the most expensive one. It is usually not the agents that we use but the skill with which we use them that determines outcome. It should never be necessary to depart from the dictum primum non nocere. Simplicity may be the key, but there is no place for double standards. Guidelines that have evolved over time in the United Kingdom, United States, and Australasia may be untenable in many parts of the world,147 but every attempt should be made to exercise the same standard of care as expected in developed countries. Our children deserve no less.

Hodges SC, Mijumbi C, Okello M, et al. Anaesthesia services in developing countries: defining the problems. Anaesthesia. 2007;62:4–11.

Walker IA, Merry AF, Wilson IH, et al. Global oximetry: an international anaesthesia quality improvement project. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1051–1060.

Walker IA, Newton M, Bosenberg AT. Improving surgical safety globally: pulse oximetry and the WHO Guidelines for Safe Surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21:825–828.

Zoumenou E, Gbenou S, Assouto P, et al. Pediatric anesthesia in developing countries: experience in the two main university hospitals of Benin in West Africa. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:741–747.

1 Andrews G, Skinner D, Zuma K. Epidemiology of health and vulnerability among children orphaned and made vulnerable by HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Care. 2006;18:269–276.

2 Hadley GP. Paediatric surgery in the third world. S Afr Med J. 2006;96:1139–1140.

3 Bickler SW, Rode H. Surgical services for children in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:829–835.

4 McQueen KA. Anesthesia and the global burden of surgical disease. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2010;48:91–107.

5 Dubowitz G. Global health and global anesthesia. Int Anesth Clin. 2010;48(2):39–46.

6 Jacob R. Pro: Anesthesia for children in the developing world should be delivered by medical anesthetists. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:35–38.

7 Walker IA, Morton NS. Pediatric healthcare—the role of anesthesia and critical care services in the developing world. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:1–4.

8 Rice MJ, Gwertzman A, Finley T, Morey TE. Anesthetic practice in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:1445–1449.

9 Towey RM, Ojara S. Intensive care in the developing world. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(Suppl 1):32–37.

10 Hodges SC, Hodges AM. A protocol for safe anaesthesia for cleft lip and palate surgery in developing countries. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:436–441.

11 Hodges SC, Mijumbi C, Okello M, et al. Anesthesia services in developing countries: defining the problems. Anaesthesia. 2007;1:4–11.

12 Steward DJ. Anaesthesia care in developing countries. Paediatr Anaesth. 1998;8:279–282.

13 Crofts IJ. Trials and tribulations of surgery in rural tropical areas. Trop Doct. 1980;10:9–14.

14 McCormick BA, Eltringham RJ. Anaesthesia equipment for resource poor environments. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(Suppl 1):54–60.

15 Ouro-Bang’na Maman AF, Kaboré RA, Zouménou E, et al. Anesthesia for children in sub-Saharan Africa—a description of settings, techniques, common presentations and outcomes. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:5–11.

16 Duke T, Subhi R, Peel D, Frey B. Pulse oximetry: technology to reduce child mortality in developing countries. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2009;29:165–175.

17 Walker IA, Wilson IH. Anaesthesia in developing countries—a risk for patients. Lancet. 2008;371:968–969.

18 Abantanga FA, Amaning EP. Paediatric elective surgical conditions as seen at a regional referral hospital in Ghana. ANZ J Surg. 2002;72:890–892.

19 Zoumenou E, Gbenou S, Assouto P, et al. Pediatric anesthesia in developing countries: experience in the two main university hospitals of Benin in West Africa. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:741–747.

20 Braz LG, Braz JRC, Modolo NSP, et al. Perioperative cardiac arrest and its mortality in children. A 9-year survey in a Brazilian tertiary teaching hospital. Pediatr Anesth. 2006;16:860–866.

21 Ahmed A, Ali M, Khan M, Khan F. Perioperative cardiac arrests in children at a university teaching hospital of a developing country over 15 years. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:581–586.

22 Hatfield AH. Anaesthesia and anaesthetic training in the Pacific Islands. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1989;17:56–61.

23 Duncan ND, Brown B, Dundas SE, et al. “Minimal intervention management” for gastroschisis: a preliminary report. West Indian Med J. 2005;54:152–154.

24 Hariharan S, Chen D, Merritt-Charles L, Rattan R, Muthiah K. Performance of a pediatric ambulatory anesthesia program—a developing country experience. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16:388–393.

25 Hoffmann E, Duck M, Oberhur A, Paul M. Anaesthesia for repair of cleft lip, maxilla and palate in Nepal. Eur J Anesthesia. 2003;20:677–678.

26 Suzuki T, Asai S. The problems in anesthetic support in developing countries. Masui. 2006;55:639–644.

27 Binam F, Lemardeley P, Blatt A, Arvis T. Anesthesia practices in Yaounde (Cameroon). Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1999;18:647–656.

28 Dunser M, Baelani I, Ganbold L. The specialty of anesthesia outside Western medicine with special consideration of personal experience in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Mongolia. Anaesthesist. 2006;55:118–132.

29 Wilhelm TJ, Anemana S, Kyamanywa P, et al. Anaesthesia for elective inguinal hernia repair in rural Ghana—appeal for local anaesthesia in resource-poor countries. Trop Doct. 2006;36:147–149.

30 Mhando S, Lyamuya S, Lakhoo K. Challengesin developing paediatric surgery in sub-Saharan Africa. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:425–427.

31 Brown TCK. Two worlds of anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1989;17:6–8.

32 Albertyn R, Bickler SW, van As AB, Millar AJW, Rode H. The effects of war on children in Africa. Paediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:227–232.

33 Schechter WS, Navedo A, Jordan D, et al. Paediatric cardiac anaesthesia in a developing country. Guatemala Heart Team. Paediatr Anaesth. 1998;8:283–292.

34 Ameh EA, Dogo PM, Nmadu PT. Emergency neonatal surgery in a developing country. Paediatr Surg Int. 2001;17:448–451.

35 Grant HW, Buccimazza I, Hadley GP. A comparison of colo-colic and ileo-colic intussusception. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1607–1610.

36 Archampong EQ. Surgery in developing countries. Br J Surg. 2006;93:516–517.

37 Wiersma R, Hadley GP. Minimizing surgery in complicated intussusceptions in the third world. Pediatr Surg. 2004;20:215–217.

38 Emmink B, Hadley GP, Wiersma R. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in a Third-World environment. S Afr Med J. 1992;82:168–170.

39 Scheepstra GL. The Dutch Interplast in Vietnam. World Anaesth. 1997;1:2.

40 Sola A, Farina D. Neonatal respiratory care and infant mortality in emerging countries. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999;27:303–304.

41 Zupan J. Perinatal mortality and morbidity in developing countries. A global view. Med Trop (Mars). 2003;63:366–368.

42 Wilson IH, Bem MJ. A view from developing countries. In: Hughes DG, Mather SJ, Wolf AR, eds. Handbook of neonatal anaesthesia. London: WB Saunders; 1996:338–350.

43 Williams RK, Adams DC, Aladjem EV, et al. The safety and efficacy of spinal anesthesia for surgery in infants: the Vermont Infant Spinal Registry. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:67–71.

44 Chowdhary SK, Chalapathi G, Narasimhan KL, et al. An audit of neonatal colostomy for high anorectal malformation: the developing world perspective. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:111–113.

45 Bosenberg A, Wiersma R, Hadley GP. Oesophageal atresia: caudothoracic epidural anaesthesia reduces the need for postoperative ventilatory support. Paediatric Surg Int. 1992;7:289–291.

46 Hodgson RE, Bosenberg A, Hadley GP. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair—impact of delayed surgery and epidural anaesthesia. S Afr J Surge. 2000;38:31–34.

47 Nwadinigwe CU, Ihezie CO, Iyidiobi EC. Fractures in children. Niger J Med. 2006;15:81–84.

48 Uppard S. Child soldiers and children associated with fighting forces. Med Confl Surviv. 2003;19:121–127.

49 Tripodi P, Patel P. HIV/AIDS peacekeeping and conflict crises in Africa. Med Confl Surviv. 2004;20:195–208.

50 Spry-Levenson J. Lessons in survival for children of war. Gemini News. 1996. Available at http://www.pangaea.org/street-children/Africa/Kigali.htm (accessed July 2012)

51 Pearn J. Children and war. J Paediatr Child Health. 2003;39:166–172.

52 Baker JN, Anghelescu DL, Kane JR. Pain still lords over children. J Pediatr. 2008;152:6–8.

53 Rabbitts JA, Groenewald CB, Dietz NM, Morales C, Räsänen J. Perioperative opioid requirements are decreased in hypoxic children living at altitude. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:1078–1083.

54 Jimenez N, Garroutte E, Kundu A, Morales L, Buchwald D. A review of the experience, epidemiology, and management of pain among American Indian, Alaska Native, and Aboriginal Canadian peoples. J Pain. 2011;12:511–522.

55 Forgeron PA, Jongudomkarn D, Evans J, et al. Children’s pain assessment in northeastern Thailand: perspectives of health professionals. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:71–81.

56 Bosenberg A, Thomas J, Lopez T, Kokinsky E, Larsson LE. Validation of a six-graded faces scale for evaluation of postoperative pain in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:708–713.

57 Bosenberg A. Pain issues in children of the developing world. Pain Res Manag. 2006;11:76B.

58 Wilson IH. Con: Anesthesia for children should be provided by medical anesthetists. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:39–41.

59 Harrison GG. Anaesthesia in Africa: difficulties and directions. World Anaesth. 1997;1:2.

60 Lertakyamanee J, Tritrakern T. Anaesthesia manpower in Asia. World Anaesth. 1999;3:13–15.

61 Sanou I, Vilasco B, Obey A, et al. Evolution of the demography of anesthesia practitioners in French speaking Sub-Saharan Africa. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1999;18:642–646.

62 World Health Organization. Safe surgery saves lives. The Second Global Patient Safety Challenge. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. 2009. Available at http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/en/ (accessed July 2012)

63 Akinyemi OO, Soyannwo AO. The choice of anaesthesia as a career by undergraduates in a developing country. Anaesthesia. 1980;35:712–715.

64 Soyannwo OA, Elegbe EO. Anaesthetic manpower development in West Africa. Afr J Med Sci. 1999;28:163–165.

65 Adesunkanmi AR. Where there is no anaesthetist: a study of 282 consecutive patients using intravenous, spinal and local infiltration anaesthetic techniques. Trop Doct. 1997;27:79–82.

66 Adnet P, Diallo A, Sanou J, et al. Anesthesia practice by nurse anesthetists in French speaking Sub-Saharan Africa. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1999;18:636–641.

67 Lacquiere DA, Courtman S. Use of the iPad in paediatric anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:629–630.

68 Dasari KB, White SM, Pateman J. Survey of iPhone usage among anaesthetists in England. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:630–631.

69 Enright A, Wilson IH, Moyers JR. The World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists: supporting education in developing countries. Anaesthesia. 2007;62(Supp 1):67–71.

70 Cote CJ. The WFSA pediatric anesthesia fellowships: origins and perspectives. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:28–29.

71 Walker IA. Con: Pediatric anesthesia training in the developing countries is best achieved by out of country scholarships. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:45–49.

72 Ouro-Bang’na Maman AF, Kaboré RA, Zouménou E, et al. Anesthesia for children in sub-Saharan Africa—a description of settings, techniques, common presentations and outcomes. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:5–11.

73 Gathuya Z. Pro: Pediatric anesthesia in developing countries is best achieved by selective out of country scholarships. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:42–44.

74 Cote CJ, Cavallieri S, Ben Ammar MS, Bosenberg A, Jacob R. Pediatric Anesthesia Fellowship Program established through the World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists. Int Anesth Clin. 2010;48:47–57.

75 Jacob R. Pro: Anesthesia for children in the developing world should be delivered by medical anesthetists. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:35–38.

76 Walker IA, Merry AF, Wilson IH, et al. Global oximetry: an international anaesthesia quality improvement project. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1051–1060.

77 Cavallieri S, Canepa P, Campos M. Evolution of the WFSA education program in Chile. Pediatr Anesth. 2009;19:38–41.

78 Children of the World Anaesthesia Foundation, Latest news, links, and conferences. Available at www.cotwaf.com (accessed July 2012)

79 UNAIDS/WHO, Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Available at http://www.unaids.org/globalreport/ (accessed July 2012)

80 Mofenson LM. Prevention in neglected subpopulations: prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(Suppl 3):S130–S148.

81 Karpelowsky JS, Leva E, Kelley B, et al. Outcomes of human immunodeficiency virus-infected and -exposed children undergoing surgery—a prospective study. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:681–687.

82 Anabwani GM, Woldetsadik EA, Kline MW. Treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in children using antiretroviral drugs. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005;16:116–124.

83 Asamoah-Odei E, Garcia Calleja JM, Boerma JT. HIV prevalence and trends in sub-Saharan Africa: no decline and large subregional differences. Lancet. 2004;364:35–40.

84 Peacock-Villada E, Richardson BA, John-Stewart GC. Post-HAART outcomes in pediatric populations: comparison of resource-limited and developed countries. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e423–e441.

85 Fowler MG, Gable AR, Lampe MA, Etima M, Owor M. Perinatal HIV and its prevention: progress toward an HIV-free generation. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:699–719.

86 Read JS. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: antiretroviral strategies. Clin Perinatol. 2010;37:765–776.

87 Sohn AH, Nuttall JJ, Zhang F. Sequencing of antiretroviral therapy in children in low- and middle-income countries. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:54–60.

88 Vermund SH. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Africa. Top HIV Med. 2005;12:130–134.

89 Lalor K. Child sexual abuse in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:439–460.

90 Thorne C, Newell ML. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004;17:247–252.

91 Graham SM. Non-tuberculosis opportunistic infections and other lung diseases in HIV-infected infants and children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:592–602.

92 Graham SM. Impact of HIV on childhood respiratory illness: differences between developing and developed countries. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36:462–468.

93 Cox JA, Lukande RL, Lucas S, et al. Autopsy causes of death in HIV-positive individuals in sub-Saharan Africa and correlation with clinical diagnoses. AIDS Rev. 2010;12:183–194.

94 Enarson PM, Gie RP, Enarson DA, Mwansambo C, Graham SM. Impact of HIV on standard case management for severe pneumonia in children. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2010;4:211–220.

95 George R, Andronikou S, Theron S, et al. Pulmonary infections in HIV-positive children. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:545–554.

96 De Vincentiis GC, Sitzia E, Bottero S, et al. Otolaryngologic manifestations of pediatric immunodeficiency. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(Suppl 1):S42–S48.

97 dos Santos Pinheiro R, França TT, Ribeiro CM, et al. Oral manifestations in human immunodeficiency virus infected children in highly active antiretroviral therapy era. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:613–622.

98 Janda S, Quon BS, Swiston J. HIV and pulmonary arterial hypertension: a systematic review. HIV Med. 2010;11:620–634.

99 Wittenberg D, Benitez CV, Canani RB, et al. HIV infection: Working Group Report of the Second World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39(Suppl 2):S640–S646.

100 De Maat MM, Ekhart GC, Huitema AD, et al. Drug interaction between antiretroviral drugs and comedicated agents. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:223–282.

101 Hughes CA, Freitas A, Miedzinski LJ. Interaction between lopinavir/rotonavir and warfarin. CMAJ. 2007;177:357–359.

102 Zhang D, Chando TJ, Everett DW, et al. In vitro inhibition of UDP glucuronosyl transferase by atazanavir and other HIV protease inhibitors and the relationship of this property to in vivo bilirubin glucuronidation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1729–1739.

103 George R, Andronikou S, du Plessis J, et al. Central nervous system manifestations of HIV infection in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:575–585.

104 Schwartz D, Schwartz T, Cooper E, Pullerits J. Anaesthesia in the child with HIV disease. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38:626–633.

105 Zar HJ, Connell TG, Nicol M. Diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children: new advances. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2010;8:277–288.

106 Verhagen LM, Warris A, van Soolingen D, de Groot R, Hermans PW. Human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis coinfection in children: challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:e63–e70.

107 Beard J, Feeley F, Rosen S. Economic and quality of life outcomes of antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS in developing countries: a systematic literature review. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1343–1356.

108 Swaminathan S, Rekha B. Pediatric tuberculosis: global overview and challenges. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(Suppl 3):S184–S194.

109 Wells T, Shingadia D. Global epidemiology of paediatric tuberculosis. J Infect. 2004;48:13–22.

110 Feja K, Saiman L. Tuberculosis in children. Clin Chest Med. 2005;26:295–312.

111 Singh H, Parakh A, Basu S, Rath B. Plasmodium vivax malaria: is it actually benign? J Infect Public Health. 2011;4:91–95.

112 Kochar DK, Tanwar GS, Khatri PC, et al. Clinical features of children hospitalized with malaria—a study from Bikaner, northwest India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:981–989.

113 Singhai T. Management of severe malaria. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:81–88.

114 Newton CR, Taylor TE, Whitten RO. Pathophysiology of fatal falciparum malaria in African children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;58:673–683.

115 Doherty C, Holtby H. Pediatric cardiac anesthesia in the developing world. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;21:609–614.

116 Hewitson JH, Brink J, Zilla P. The challenge of pediatric cardiac services in the developing world. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;14:340–345.

117 Neirotti R. Paediatric cardiac surgery in less privileged parts of the world. Cardiol Young. 2004;14:341–346.

118 Bhagwanjee S, Bosenberg AT, Muckart DJ. Management of sympathetic overactivity in tetanus with epidural bupivacaine and sufentanil: experience with 11 patients. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1721–1725.

119 Thwaites CL, Yen LM, Cordon SM, et al. Effect of magnesium sulphate on urinary catecholamine excretion in severe tetanus. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:719–725.

120 Freshwater-Turner D, Udy A, Lipman J, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in tetanus—what lessons can be learnt with specific reference to alpha-2 agonists? Anaesthesia. 2007;62:1066–1070.

121 Fenton PM. The cost of Third World anaesthesia: an estimate of consumption of drugs and equipment in anaesthetic practice in Malawi. Cent Afr J Med. 1994;40:137–139.

122 Meo G, Andreone D, De Bonis U, et al. Rural surgery in southern Sudan. World J Surg. 2006;30:495–504.

123 Fenton PM. The Malawi anaesthetic machine. Anaesthesia. 1989;44:498–503.

124 Ezi Ashi TI, Papworth DP, Nunn JF. Inhalational anaesthesia in developing countries. Anaesthesia. 1983;38:729–735.

125 Aguemon AR, Terrier G, Lansade A, et al. Caudal and spinal anesthesia in sub-umbilical surgery in children. Apropos of 1875 cases. Cah Anesthesiol. 1996;44:455–463.

126 Bosenberg A. Pediatric regional anaesthesia: an update. Pediatr Anesth. 2004;14:398–402.

127 Bosenberg AT, Bland BA, Schulte-Steinberg O, Downing JW. Thoracic epidural anaesthesia via caudal route in infants. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:265–269.

128 Bosenberg AT. Lower limb nerve blocks in children using unsheathed needles and a nerve stimulator. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:206–210.

129 Ayob Y. Hemovigilance in developing countries. Biologicals. 2010;38:91–96.

130 Farrugia A. Globalisation and blood safety. Blood Rev. 2009;23:123–128.

131 Sullivan P. Developing an administrative plan for transfusion medicine—a global perspective. Transfusion. 2005;45:224S–240S.

132 Dhingra N, Lloyd SE, Fordham J, Amin NA. Challenges in global blood safety. World Hosp Health Serv. 2004;40:45–52.

133 World Health Organization (WHO), Blood safety and donation a global view. Fact sheet 279, November 2009. Available at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs279 (accessed July 2012)

134 Volkow P, Del Rio C. Paid donation and plasma trade: unrecognised forces that drive the AIDS epidemic in developing countries. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:5–8.

135 Barcelona SL, Thompson AA, Cote CJ. Intraoperative pediatric blood transfusion therapy: a review of common issues. Part II: transfusion therapy, special considerations, and reduction of allogenic blood transfusions. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15:814–830.

136 Khambatta HJ, Westheimer DN, Power RW, Kim Y, Flood T. Safe, low-technology anesthesia system for medical missions to remote locations. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:1354–1356.

137 Eltringham RJ, Varvinski A. The Oxyvent. An anaesthetic machine designed to be used in developing countries and difficult situations. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:668–672.

138 Eltringham RJ, Nazal A. The Glostavent: an anesthetic machine for use in developing countries and difficult situations. World Anaesth. 1999;3:9–10.

139 Bosenberg A. Special problems in developing countries. In: Bissonette B, Dalens BJ, eds. Pediatric anesthesia principles and practice. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002.

140 Duke T, Peel D, Graham S, et al. Oxygen concentrators: a practical guide for clinicians and technicians in developing countries. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2010;30:87–101.

141 Howie SR, Hill S, Ebonyi A, et al. Meeting oxygen needs in Africa: an options analysis from the Gambia. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:763–771.

142 Jarvis DA, Brock-Utne JG. Use of an oxygen concentrator linked to a draw-over vaporiser (anaesthetic delivery system for underdeveloped nations). Anesth Analg. 1991;72:805–810.

143 Fisher Q. Anesthesia in the developing world. Soc Pediatr Anesth Newsletter. 1999;12(1):15.

144 Schneider WJ, Politis GD, Gosain AK, et al. Volunteers in plastic surgery guidelines for providing surgical care for children in the less developed world. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2477–2486.

145 Politis GD, Schneider WJ, Van Beek AL, et al. Guidelines for pediatric perioperative care during short-term plastic reconstructive surgical projects in less developed nations. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:183–190.

146 Bridenbaugh PO. Role of anesthesiologists in global health: can one volunteer make a difference? Int Anesth Clin. 2010;48(2):165–175.

147 Fisher QA, Nichols D, Stewart FC, et al. Assessing pediatric anesthesia practices for volunteer medical services abroad. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:1315–1322.

148 Fisher QA, Politis G, Tobias JD, et al. Pediatric anesthesia for voluntary services abroad. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:336–350.

149 Unger F, Ghosh P. International cardiac surgery. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;14:321–323.

150 Bosenberg AT. Pediatric anesthesia in developing countries. Curr Opin Anesthesiol. 2007;20:204–210.