Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology

Normal Genital Anatomy

The genital tract undergoes visible morphologic changes from infancy through childhood and adolescence.1,2 At birth, owing to the influence of maternal circulating estrogens, the labia majora are anteriorly placed and edematous. They are thickened and cover the introital opening. The clitoral proportion is also larger. The vestibule and hymen are pale and thickened, and can occlude visualization of the vaginal canal without manipulation. The vagina is rugated and moist, and vaginal secretions may be present. The cervix is visible, and the uterus may contain functioning endometrial tissue, which can result in estrogen-withdrawal bleeding in infancy.

During early childhood, the vulva remodels with thinning and attenuation of the labia majora and minora. The vestibule becomes erythematous with prominent vascular markings. It may now be unopposed by the labia, allowing for easy visualization of the vaginal orifice with minimal retraction. The hymen of a prepubescent female is normally easily visualized and is thin, often translucent, and inelastic. Normal variations in the shape and amount of hymenal tissue have been described (Fig. 74-1).3–5 The vagina has an erythematous appearance without rugations. Normally, the pH is mildly basic and a mixture of bacterial flora is present. The cervix is flush with the vaginal vault and the uterine fundus is poorly developed, with no endometrial development.

FIGURE 74-1 Normal anatomic variations of the hymen. (Adapted from Pokorny SF, Stormer J. Atraumatic removal of secretions from the prepubertal vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;156:581–3.)

With the onset of puberty, the vestibule begins to lose its erythematous appearance. The hymen thickens and becomes elastic and redundant.6 The vagina grows in length and develops rugations. The cervix has a well-defined junction from the uterus, and the uterine fundus develops a rounded appearance. Endometrial tissue is present.

Follicular activity within the ovary, with small cyst formation, can be observed on imaging as early as 16 weeks of gestation.7 Three to 5% of children have small incidental ovarian cysts detected on ultrasound (US).8 Follicular growth followed by involution continue throughout childhood, with increased follicular activity and size coinciding with increasing age.9 Ovarian volume and position change with age, with the ovaries being intra-abdominal in childhood and assuming a pelvic position at puberty.

Genital Examination

An adequate light source and proper positioning are usually all that are needed to accomplish an examination in a prepubertal child.10 For visualization of the vulva, introital opening, and lower vagina, gentle downward traction on the labia in a lithotomy position is usually successful (Fig. 74-2). The knee–chest position may offer a clearer view of the hymen and lower vagina (Fig. 74-3).11 A colposcope (or otoscope) may be helpful to see the detail of the vestuble and lower vagina.12 The office use of vaginal speculums is discouraged in prepubertal children. When vaginal inspection is needed, it should be done using endoscopic instruments under sedation.13,14 By gently occluding the vaginal orifice, the entire vaginal canal can be visualized with hydrodistention.15 Speculum examinations of the vagina are usually well tolerated in postpubertal girls when a narrow-caliber straight blade speculum is gently inserted. Bimanual examinations can be accomplished through a rectal approach or, in adolescents, with a single digit inserted into the vaginal fornix. Imaging with abdominal ultrasound or, occasionally magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is adjuvant to examination and provides additional information about the upper genital tract.16

FIGURE 74-2 Examination of the genitalia by labial traction. Gently grasping the posterior labia majora and pulling anteriorly and superiorly allows visualization of the genital structures.

FIGURE 74-3 Knee–chest positioning. The lower vagina and hymen can occasionally be viewed more successfully by using the knee–chest position.

Vulvar Abnormalities

Vulvar pruritus, pain, and discharge are common complaints in children. An etiology can be obtained in most cases with careful external inspection and, if necessary, blind vaginal cultures. Biopsy is seldom indicated. Most often, symptoms involve irritation or eruption of the vulvar skin related to hygiene or common skin conditions. Atopic or irritant dermatitis are the most common diagnoses.17 Infections are associated with acute inflammation with mucosal erythema and the presence of a vaginal discharge.18 Common respiratory pathogens such as Streptococcus pyogenes and Haemophilus influenzae may occasionally cause acute genital symptoms.19,20 When a bacterial infection is suspected, cultures of the vagina can be obtained by using moistened urethral swabs, feeding tubes, or catheters.

Vulvar dermatoses can lead to acute vulvovaginal symptoms. Lichen sclerosis has the hallmark characteristic of a loss of skin markings with a sharply demarcated pale epithelial ring encircling the introitus, but sparing the vagina (Fig. 74-4). Signs of inflammation and trauma may be present, with purpura, fissures, and secondary infection associated with scratching. Principles of treatment include avoidance of irritation and loose clothing, mild soaps, and the generous use of emollients. Early treatment with ultrapotent corticosteroids may be effective in reducing symptoms of lichen sclerosis and minimizing long-term scarring. In 20% of patients, ultrapotent corticosteroids have been shown to reverse skin changes.21 Tacrolimus has also been reported to offer similar benefit to pediatric patients.22 Other dermatologic conditions such as psoriasis, eczema, and allergic dermatitis also may mimic vulvovaginitis.19

FIGURE 74-4 Lichen sclerosis diagnosed in a 5-year-old. A sharp demarcation of hypopigmented, thin epithelium is seen. This lesion is often associated with fissures and purpura.

Labial adhesions occur frequently in prepubescent girls (Fig. 74-5). Adhesions are thought to occur because of irritation or trauma to the unestrogenized labia. Adhesions can be associated with urinary tract infections, perineal wetness, symptomatic vulvitis, and an inability to access the urethra. When symptomatic, preferred treatment has historically been estrogen-based cream applied under traction to the labia. Newer investigations suggest that betamethasone cream may have equal efficacy.23,24 The need for adhesiolysis is low because of the efficacy of topical therapy, but may be necessary in both unusually dense adhesions or those that have required previous separation. Manual separation of the adhesions without anesthesia should be avoided because of the discomfort and the high risk of recurrence. For thin adhesions, office separation using long acting local anesthetics, such as EMLA cream, is a reasonable option.25

Genital Bleeding

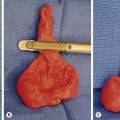

Bleeding from the genital area in a prepubescent child is always abnormal (Box 74-1). Bleeding is most commonly extragenital, resulting from hematuria, rectal fissures, and vulvar epithelial irritation. Prolapse of the urethra can occur and may be associated with bleeding or even gangrenous changes (Fig. 74-6). Topical treatment with estrogen-based cream usually relieves the symptoms. If symptoms persist, excision of the redundant tissue may be necessary.26 Vaginal bleeding can be associated with precocious puberty or autonomous production, or with exogenous sources of hormonal stimulation. It is important to perform a detailed physical examination searching for evidence of breast development, estrogenization of the genital tract, or the presence of an abdominal mass. In the absence of a satisfactory explanation for the source of bleeding, vaginoscopy should be performed to exclude a foreign body, trauma, infection or, rarely, primary and metastatic tumors of the lower genital canal (Fig. 74-7).

FIGURE 74-6 Urethral prolapse was found in this 6-year-old child with a history of recurrent painless genital bleeding.

FIGURE 74-7 A 12-year-old adolescent, presenting with refractory dysfunctional uterine bleeding, is diagnosed with a neuroendocrine tumor of the cervix at vaginoscopy.

Acute genital bleeding in children requires immediate evaluation for the presence of serious injury or sexual abuse.27 If the source of bleeding is not readily apparent, if the entire lesion cannot be identified, or if the patient is not tolerant of the examination, vaginoscopy under sedation is needed.28,29 Straddle injuries are common during childhood from accidental falls onto blunt objects, resulting in soft tissue trauma from striking the perineum. Straddle injuries usually involve the mons, clitoris, and labia, sparing the vaginal ring or perineal body (Fig. 74-8). They may result in a hematoma, linear lacerations, or abrasions. Vulvar hematomas can be extensive but are more commonly self-limited. In the absence of acute ongoing hemorrhage, small or moderate hematomas can be managed conservatively with bed rest, ice, and pain control. Evacuation of extremely large hematomas causing distortion of the midline pelvic structures occasionally is necessary to facilitate recovery. Evacuation with debridement should be performed with the child under anesthesia by incising the medial mucosal surface and placing absorbable sutures for hemostasis and closure of dead space.

FIGURE 74-8 An extensive vulvar hematoma is seen after a straddle injury. (Courtesy of Diane Merritt, MD.)

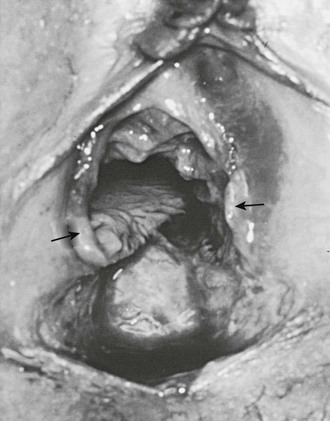

Penetrating injuries can occur through accidental impalements onto irregular objects, but the possibility of sexual abuse must always be considered (Figs 74-9 and 74-10). In the prepubertal child, lacerations involving or occurring above the hymenal ring require vaginoscopy under general anesthesia. Because of the inelasticity of the vaginal epithelium, penetrating injuries can result in disruption of the vagina, with possible internal hemorrhage and hematoma formation.29 Injuries that cannot readily be explained by the history should be referred to child protection. Surgeons should familiarize themselves with the legal and social resources for sexual abuse and care that are available within their communities.

FIGURE 74-9 A 9-year-old girl has a penetrating posterior vaginal injury sustained after falling onto an open cabinet. A urinary catheter has been inserted in the urethra.

FIGURE 74-10 An 8-year-old victim of acute sexual assault has small bowel herniating through the apex of the avulsed vagina. Note the abundant, although transected, amount of hymenal tissue (arrows) present, indicating that she had not had significant stretch trauma to her hymen before this episode of rape. (From Pokorny SF, Pokorny WJ, Kramer W. Acute genital injury in the prepubertal girl. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992;166:1461–6.)

Introital masses in children occasionally come to the attention of surgeons. Masses of the introitus or vagina are most commonly epithelial inclusion cysts of the hymen or lower vagina, and often spontaneously resolve. There is a rare possibility of embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma, a malignant primary tumor that appears as indolent, grape-like masses protruding from the vagina (Fig. 74-11). Other possibilities include condylomata acuminata, ectopic ureter, or an obstructive vaginal anomaly. Occasionally, the Bartholin gland or periurethral gland may occlude or form an abscess, leading to an acquired lateral mass. Transperineal ultrasound can be helpful. In cases that are unclear, biopsy or excision (or both) may be necessary.

Uterovaginal Anomalies

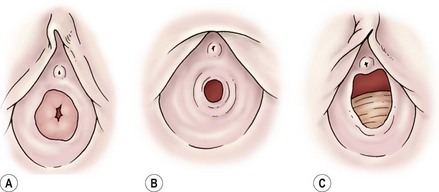

Imperforate hymen is the most commonly diagnosed obstructive anomaly, but has an incidence of less than 1%.30 It arises as an isolated anomaly from failure of canalization of the urogenital sinus. Symptoms typically are first noted during late puberty with cyclic pelvic pain and introital distention, associated with the absence of menstruation. With the continued accumulation of menstrual blood, a pelvic mass and obstructive genitourinary or gastrointestinal symptoms may develop. Occasionally, newborns will present with mucous accumulation and an abdominal mass (Fig. 74-12). Transabdominal ultrasound reveals a dilated vaginal and uterine canal. If this is found during childhood and is asymptomatic, correction is usually deferred until the onset of puberty. Surgical excision of the hymen with evacuation of the retained menstrual fluid provides permanent relief (Fig. 74-13). An incision is made in the membrane inferior to the urethral meatus. After decompression, the individual flaps of tissue are then excised. The vaginal mucosa is sutured to the introital edge with interrupted absorbable sutures to avoid stenosis (Fig. 74-14). It is important to recognize that significant distention of the posterior vaginal wall may cause the hymenal membrane to be located in a more superior position. Needle aspiration without definitive surgical correction is contraindicated because of the possibility of bacterial seeding and the development of an abscess.

FIGURE 74-13 (A) Imperforate hymen in a 12-year-old girl with a 6-month history of recurrent abdominal pain. (B) Evacuation of the menstrual obstruction at hymenotomy.

FIGURE 74-14 (A) Imperforate hymen. (B) A cruciate incision is made in the apex of the hymen after identifying the outer hymenal borders. (C) The hymenal remnants are trimmed. (D) Interrupted sutures are utilized for hemostasis.

A transverse vaginal septum, either complete or partial, can be found at various levels of the vagina due to failure of unification of the urogenital sinus and the Müllerian ducts during embryogenesis (Fig. 74-15). As the introitus can appear normal, the diagnosis may be delayed. MRI or ultrasound are helpful in defining this anomaly and documenting the thickness of the septum prior to surgical exploration.31 Operative correction entails excision of the septum with a mucosal anastomosis. A thick septum may require preoperative vaginal dilation, mobilization of the upper vagina, or occasionally a skin graft to maintain vaginal patency. Circumferential stenosis is common at the anastomotic site, particularly with high or thick septae. Vaginal dilation or stent placement may be necessary. Occasionally, a uterine duplication is associated with hypoplasia of one cervix and obstruction. This condition is treatable with laparoscopic hemihysterectomy of the affected side.32 True cervicovaginal agenesis is rare and is associated with an obstructed uterine canal, the absence of a patent cervix, and agenesis of the upper vagina (Fig. 74-16). This condition has a poor prognosis for reconstruction, with reports of significant morbidity from ascending infection and even death.33 Hysterectomy is usually recommended, but creation of a vagino-uterine fistula has also been described.34,35

FIGURE 74-15 The transverse vaginal septum is the result of failed unification or canalization of the urogenital sinus and the müllerian duct. It can arise anywhere in the vagina, but is most common in the upper vagina.

FIGURE 74-16 A sonographic sagittal view of the pelvis of a 16-year-old girl with cervicovaginal agenesis and a resultant hematometra. Note the dilated vagina and uterus (UT).

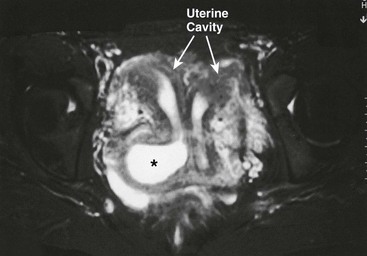

Occasionally, patients may be seen with a duplication of the uterus and cervix, and a unilateral obstructing longitudinal septum of the vagina. Associated ipsilateral renal agenesis or hypoplasia is commonly found.36 Menstruation occurs from the nonobstructed side, so the diagnosis may be made well past menarche with pelvic ultrasound or MRI (Fig. 74-17).31,37 Repair through a vaginal approach is performed at diagnosis, with complete excision of the vaginal septum.

FIGURE 74-17 MR image of a 16-year-old girl with a complete uterine duplication and a blind right hemivagina. Note the obstructed and dilated right hemivagina (asterisk) and the resultant right-sided hematocolpos and hematometra.

Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster-Hauser syndrome was first described in 1961 and includes primary amenorrhea in women with normal secondary sexual characteristics, uterine hypoplasia, and congenital absence of the upper vagina.38 The incidence is approximately 1 in 5000.39 Renal and skeletal anomalies are commonly associated with this disorder. Although patients have primary amenorrhea, pubertal development and ovarian function are normal. The diagnosis can be made clinically on the basis of a normal phenotype, chromosomal analysis, and the genital findings cited earlier. Management is centered on creation of an adequate vaginal pouch to allow normal sexual functioning. The use of Lucite dilators, first popularized in the 1930s, has provided a highly effective nonsurgical alternative for many patients with vaginal agenesis (Fig. 74-18).40,41 Through the use of successive pressure dilators introduced at the hymenal ring over a 2-3-month period, the vaginal vault can be lengthened and enhanced to provide adequate vaginal capacity. This approach has the advantage of being patient controlled and is associated with extremely low morbidity. Sexual satisfaction of young women treated with dilation has been shown to be comparable with the normal population.42 In selected patients, operative creation of an artificial vagina may be needed.43

FIGURE 74-18 Sequential vaginal dilators are often used to create a coital pouch in individuals with vaginal agenesis.

Many surgical options for vaginal substitution have been described, with the split-thickness skin graft vaginoplasty being advocated most often for patients with agenesis (Fig. 74-19).44 Surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction remain high for this type of vaginoplasty although risks and complications exist.45 Other materials such as amnion, peritoneum, absorbable adhesion barriers (Interceed, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), and buccal mucosa have been described as an alternative to skin grafting.46,47 Novel laparoscopic techniques using these alternatives have also been reported including laparoscopic methods using advancement of the peritoneum or a transperitoneal pulley system to advance the neovagina.48,49 The use of sigmoid bowel pedicles pulled to the introitus for vaginal creation is less commonly utilized for this problem, but also may be associated with good long-term results.50,51

FIGURE 74-19 Creation of a vaginal pouch by using a split-thickness free graft is shown. (A) The perineum of a patient with vaginal agenesis is seen. (B) A speculum has been introduced into the space that has been created between the urethra and rectum. (C) Covering of a vaginal mold with split-thickness grafted skin. (D) Placement of the mold into the space noted in (B).

Adnexal Disease

Ovarian cysts may develop at any time from fetal life to adulthood. Simple cysts in the neonate are generally follicular and originate from the influence of maternal estrogens. Complex masses in this age group may represent in utero or neonatal torsion with the risk of malignancy being very low.52 Both simple and complex masses are likely to resolve without therapy, but operative intervention may be necessary for torsion, hemorrhage, or mass effect.52 Percutaneous aspiration is indicated for cysts larger than 5 cm to minimize the risk of torsion.53,54 Indications for operative intervention include the presence of a complex mass that fails to resolve in the neonatal period, the recurrence of a cyst after aspiration, the development of acute abdominal symptoms, or a combination. Treatment consists of laparoscopic fenestration of simple cysts or cystectomy.55

In childhood, small cysts representing follicular development and atresia are common and not pathologic.8 Management of ovarian cysts in children is based on size, the presence of symptoms, and cyst composition. Worrisome findings include cysts larger than 5 cm, cysts with solid or complex internal echoes on ultrasound, and fixed masses accompanied by systemic symptoms of disease or precocious development.56

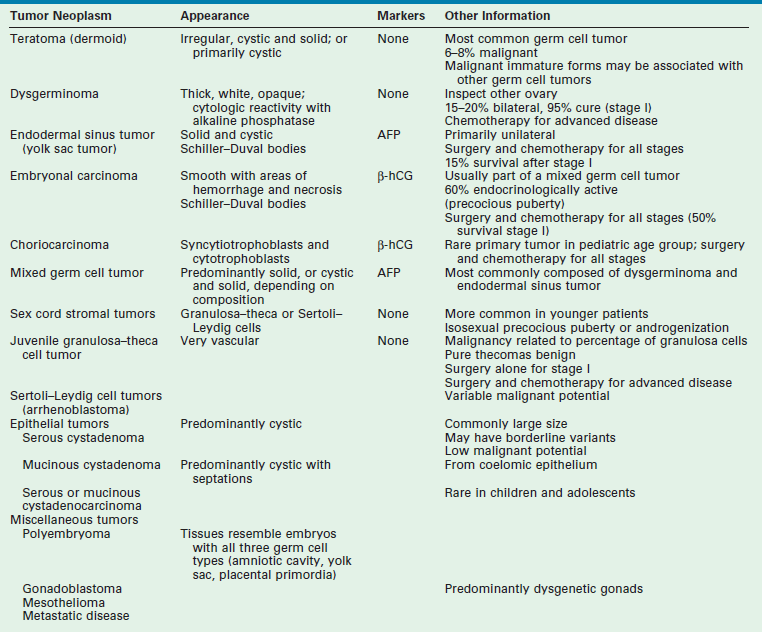

Occasionally, cysts may be associated with breast development or vaginal bleeding (Fig. 74-20). The diagnosis of an ovarian tumor must be considered in children, especially in those with a large, persistent complex mass that has solid components (Table 74-1). The most common ovarian tumor in children is a mature cystic teratoma, followed by stromal tumors.57,58 Malignant tumors are rare, comprising less than 10% of all operatively treated masses.57–59

TABLE 74-1

Neoplasms in Female Children and Adolescents

AFP, α-fetoprotein; β-hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin.

FROM BACON JL: Surgical treatment of adnexal pathology. In Hewitt G (ed): Operative Techniques in Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1999, vol 4, p 215.

FIGURE 74-20 (A) A 6-year-old girl presented with precocious puberty and a large pelvic mass. (B) An autonomously functioning ovarian serous cystadenoma was found. All pubertal signs regressed after its removal.

Ovarian cysts are extremely common in adolescence because of persistent anovulation or ovulatory dysfunction. They may be associated with rupture, pain, or hemorrhage (Fig. 74-21). A mass in the pelvis may be present, or the cyst may be found incidentally at the time of other studies. In adolescents, a variety of reproductive disorders such as endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, disorders of the fallopian tube, congenital uterine anomalies, or disorders of pregnancy can have the appearance of ovarian cysts (Box 74-2). It is essential to elicit a full history, including the details of menstrual function and sexual activity. Pregnancy needs to be excluded, and the possibility of complications of a sexually transmitted infection considered. Ultrasound is very helpful in the management of ovarian cysts in adolescents.60

FIGURE 74-21 A ruptured corpus luteum cyst in a 15-year-old girl with acute pelvic pain. The site of rupture is marked by the arrow.

The conservative approach to the management of ovarian cysts in adolescents is based on the low rate of malignancy and the high rate of functional cysts or benign tumors. Observation is recommended as an initial therapy. Indications for operation include cysts larger than 10 cm, persistent complex masses, acute symptoms, or a high suspicion for malignancy. In the absence of findings suggestive of neoplasm, laparoscopy can be paired with cystectomy and ovarian conservation. Cystectomy is performed by incising the ovary on the antimesenteric portion of the ovary. Blunt dissection separates the cyst from the ovarian capsule, allowing the cyst wall to be removed in toto (Fig. 74-22). Electrocautery or sutures may be needed to obtain hemostasis. Closure of the cyst wall is not necessary. Although marked distortion of the ovarian capsule may occur, rapid involution develops. Studies have found laparoscopic removal of ovarian teratomas to be safe, efficient, and without long-term sequelae, even in the presence of rupture and spillage (Fig. 74-23).61,62 When malignancy is suspected, oophorectomy through a midline laparotomy incision allows proper staging with careful exploration, collection of pelvic cytology, and pelvic and periaortic lymph node sampling.

FIGURE 74-22 Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy. (A) An incision is made on the antimesenteric portion of the ovary. (B) The capsule is separated from the ovarian cyst with blunt and sharp dissection.

FIGURE 74-23 A 14-year-old presented with abdominal pain. Ultrasonography and CT showed calcifications within this left ovarian mass (A), indicating that it was a likely ovarian teratoma. (B) Laparoscopic excision of the teratoma was initiated by incising the outer layer and peeling back the normal ovarian parenchyma (asterisk). (C) The ovarian parenchyma (asterisk) has almost been completely stripped from the teratoma. (D) The ovarian parenchyma was approximated after excision of the mass. The teratoma was placed into an endoscopic retrieval bag and exteriorized through the umbilicus after some morcellation. Histologic examination showed it to be a benign teratoma.

The ovaries or tubes may occasionally undergo torsion, with ischemia and ultimately necrosis of the adnexa, creating a surgical emergency (Fig. 74-24). Torsion of the ovary is recognized by the acute onset of pain, nausea, vomiting, and a pelvic mass. Ovarian torsion is classically associated with the presence of an ovarian cyst or tumor, but can occur in normal ovaries.63 Doppler-enhanced ultrasound demonstrating the absence of blood flow has historically been used to diagnose ovarian torsion, but has been shown to be less predictive than ovarian enlargement.64,65 If a prompt diagnosis is made, the ovary may be salvaged with detorsion and cystectomy, even when it visually appears to have vascular compromise.66 Oöphorectomy is reserved for necrotic ovaries. Oöphoropexy by side-wall fixation or shortening of the meso-ovarian ligament has been advocated by some to decrease the risk of subsequent contralateral torsion, although there is no evidence showing its efficacy.66

FIGURE 74-24 Right ovarian torsion in a 14-year-old girl with acute abdominal pain (A). The fallopian tube and ovarian vascular pedicle are twisted several times (arrow), resulting in acute venous congestion. (B) Untwisting the pedicle (arrow) allowed return of arterial flow and resolution of the venous congestion. Although the ovary appeared ischemic, it was not removed.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis refers to the presence of endometrial glands and functioning stroma outside the uterine lining. Traditionally, endometriosis has been thought to be a disease of women in their 20s and 30s, and is well described in the adolescent population with the exact prevalence unknown. As many as 75% of adolescent girls with medically refractory pelvic pain are found to have endometriosis at laparoscopy.67 Although symptoms can suggest the diagnosis, definitive diagnosis is made by laparoscopic visualization or biopsy (or both). Clear, vesicular-appearing lesions and low-stage disease are more common in adolescence, with more classic hemosiderin ‘powder burn lesions’ identified in older adults (Fig. 74-25).68,69

FIGURE 74-25 (A) The peritoneal surface of a 14-year-old with endometriosis. Note the hypervascularity and subtle vesicular type lesions. (B) The peritoneal surface of a 17-year-old with endometriosis. Note the classic ‘powder burn’ appearance.

The treatment in adolescents is based on alleviation of symptoms and slowing the progression of disease. For patients undergoing an operation, removal of all visible lesions by resection or destruction should be performed. Menstrual suppression with oral contraceptives or progesterone-only medication (or both), along with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, are the mainstays of therapy. Gonadotropin-releasing agonists may be used on a short-term basis as an adjuvant to operation, but carries the risk of a detrimental effect on bone density. This therapy should be used cautiously in younger adolescents. Likewise, newer therapies that control the symptoms of endometriosis, such as the Levonorgestrel IUS (Schering Health, Berlin-Wedding, Germany) and aromatase inhibitors, have not been studied in adolescents.70,71 Noninterventional pain therapies may have a place in managing the chronic pain associated with endometriosis. The long-term outcomes, including infertility and chronic pain, in those diagnosed with endometriosis as adolescents is not well known.

References

1. Huffman, JW, Dewhurst, CJ, Caparo, VJ. Anatomy and physiology. The Gynecology of Childhood and Adolescence, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1981.

2. Siegfried, EC, Frasier, LD. The spectrum of anogenital diseases in children. In: Callen JP, ed. Current Problems in Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997:35–80.

3. Pokorny, SF. Configuration of the prepubertal hymen. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987; 157:950–956.

4. McCann, J, Wells, R, Simon, M, et al. Genital findings in prepubertal girls selected for nonabuse: A descriptive study. Pediatrics. 1990; 86:428–439.

5. Berenson, AB, Hegar, AH, Hayes, JM, et al. Appearance of the hymen in prepubertal girls. Pediatrics. 1992; 89:387–394.

6. Edgardh, K, Ormstad, K. The adolescent hymen. J Reprod Med. 2002; 47:710–714.

7. Peters, H, Himelstein-Braw, R, Faber, M. The normal development of the ovary in childhood. Acta Endocrinol. 1976; 82:617–630.

8. Millar, DM, Blake, JM, Stringer, DA, et al. Prepubertal ovarian cyst formation: 5 years’ experience. Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 81:434–437.

9. Himelstein-Braw, R, Byskov, AG, Peters, H, et al. Follicular atresia in the infant human ovary. J Reprod Fertil. 1976; 46:55–59.

10. Hariston, L. Physical examination of the prepubertal girl. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 40:127–134.

11. McCann, J, Welis, R, Simon, M, et al. Comparison of genital examination techniques in prepubertal girls. Pediatrics. 1990; 85:182–187.

12. Mendriatta, V. Office gynecologic evaluation of the pediatric patient: Indications, examination, and procedures. In: Hewett G, ed. Operative Techniques in Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999:164–175.

13. Golan, A, Lurie, S, Sagio, R, et al. Continuous-flow vaginoscopy in children and adolescents. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000; 7:526–528.

14. Parker, JD, Hibbert, ML, Dainty, LD, et al. Micro-hydrovaginoscopy in examining children. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 96:772–774.

15. Nakhal, RS, Wood, D, Creighton, SM. The role of examination under anesthesia (EUA) and vaginoscopy in pediatric and adolescent gynecology- a retrospective review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012; 25:64–66.

16. Teele, RL, Share, JC. Ultrasonography of the female pelvis in childhood and adolescence. Radiol Clin North Am. 1992; 30:743–758.

17. Fischer, G, Rogers, M. Vulvar disease in children: A clinical audit of 130 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000; 17:1–6.

18. VanEyk, N, Allen, L, Giebrecht, E, et al. Pediatric vulovaginal disorders: A diagnostic approach and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2009; 31:850–862.

19. Straumanis, JP, Bocchini, JA. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal vulvovaginitis in prepubertal girls: A case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1990; 9:845–847.

20. Cox, RA. Haemophilus influenzae: An underrated cause of vulvovaginitis in young girls. J Clin Pathol. 1997; 50:765–768.

21. Cooper, SM, Gao, XH, Powell, JJ, et al. Does treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosis influence its prognosis? Arch Dermatol. 2006; 140:702–706.

22. Matsumoto, Y, Yamamoto, T, Isobe, T, et al. Successful treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a child with low-concentration topical tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatol. 2007; 34:114–116.

23. Bacon, JL. Prepubertal labial adhesions: Evaluation of a referral population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 187:327–332.

24. Kumetz, LM, Quint, EH, Fisshea, S, et al. Estrogen treatment success in recurrent and persistent labial agglutination. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006; 19:381–384.

25. Hoebeke, P, Depauw, P, Van Laecke, E, et al. The use of EMLA cream as an anaesthetic for minor urological surgery in children. Acta Urol Belg. 1997; 65:25–28.

26. Holbrook, C, Misra, D. Surgical management of urethral prolapsed in girls: 13 years’experience. BJU. 2012; 110:132–134.

27. Scheidler, MG, Schultz, BL, Schall, L, et al. Mechanisms of blunt perineal injury in female pediatric patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2000; 35:1317–1319.

28. Merritt, DF. Genital trauma in children and adolescents. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 51:237–248.

29. Pokorny, SF, Pokorny, WJ, Kramer, W. Acute genital injury in the prepubertal girl. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992; 166:1461–1466.

30. Hager, AH, Ticson, L, Guerra, L, et al. Appearance of the genitalia in girls selected for nonabuse: Review of hymenal morphology and nonspecific findings. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2002; 15:27–35.

31. Lang, IM, Babyn, P, Oliver, GD. MR imaging of paediatric uterovaginal anomalies. Pediatr Radiol. 1999; 29:163–170.

32. Lee, CL, Wang, CJ, Swei, LD, et al. Laparoscopic hemi-hysterectomy in treatment of a didelphic uterus with a hypoplastic cervix and obstructed hemivagina. Hum Reprod. 1999; 14:1741–1743.

33. Casey, AC, Laufer, MR. Cervical agenesis: Septic death after surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 1997; 90:706–707.

34. Rock, JA, Schlaff, WD, Jones, HW, Jr. The clinical management of congenital absence of the uterine cervix. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1984; 22:231–235.

35. Deffarges, JV, Haddad, B, Musset, R, et al. Utero-vaginal anastomosis in women with uterine cervix atresia: Long-term follow-up and reproductive performance: A study of 18 cases. Hum Reprod. 2001; 16:1722–1725.

36. Woolfe, RB, Allen, WM. Concomitant malformations: The frequency, simultaneous occurrence of congenital malformations of the reproductive and urinary tracts. Obstet Gynecol. 1954; 2:236–265.

37. Fedele, L, Ferrazzi, E, Dorta, M, et al. Ultrasonography in the differential diagnosis of double uteri. Fertil Steril. 1988; 50:361–364.

38. Hauser, GA, Schreiner, WE. Das Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser syndrome. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1961; 91:381–384.

39. Evans, TN, Poland, ML, Boving, RL. Vaginal malformations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981; 141:910–920.

40. Frank, RT. The formation of an artificial vagina without operation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1938; 35:1053–1055.

41. Edmonds, DK, Rose, G, Lipton, MG, et al. Das Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser syndrome: A review of 245 consecutive cases managed by a multidisciplinary approach with vaginal dilators. Fertil Steril. 2012; 97:686–690.

42. Nadarajah, S, Quek, J, Rose, GL, et al. Sexual function in women treated with dilators for vaginal agenesis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2005; 18:39–42.

43. Rock, JA, Jones, HW, Jr. Construction of a neovagina for patients with a flat perineum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989; 160:845–851.

44. Wiser, WL, Bates, W. Management of agenesis of the vagina. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984; 159:108–112.

45. Martinez-Mora, J, Isnard, R, Castellvi, A, et al. Neovagina in vaginal agenesis: Surgical methods and long-term results. J Pediatr Surg. 1992; 27:10–14.

46. Morton, KE, Dewhurst, CJ. Human amnion in the treatment of vaginal malformations. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986; 93:50–54.

47. Jackson, ND, Rosenblatt, PL. Use of intercede absorbable adhesion barrier for vaginoplasty. Obstet Gynaecol. 1994; 84:1048–1050.

48. Dietrich, JE, Hertweck, P, Traynor, MP, et al. Laparoscopically assisted creation of a neovagina using the Louisville modification. Fertil Steril. 2007; 88:1431–1434.

49. Darwish, AM. A simplified novel laparoscopic formation of neovagina for cases of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2007; 88:1427–1430.

50. Kapoor, R, Sharma, DK, Singh, KJ, et al. Sigmoid vaginoplasty: Long-term results. Urology. 2006; 67:1212–1215.

51. Karateke, A, Haliloglu, B, Parlak, O, et al. Intestinal vaginoplasty: Seven years experience of a tertiary center. Fertil Steril. 2010; 94:2312–2316.

52. Monnery-Noche, ME, Auber, F, Jouannic, JM, et al. Fetal and neonatal ovarian cysts: Is surgery indicated? Prenat Diagn. 2008; 28:15–20.

53. Shozu, M, Akasofu, K, Lika, K, et al. Treatment of antenatally diagnosed fetal ovarian cysts by needle aspiration during the neonatal period. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1991; 2149:103–106.

54. Kessler, A, Nagar, H, Graif, M, et al. Percutaneous drainage as the treatment of choice for neonatal ovarian cysts. Pediatr Radiol. 2006; 37:330–332.

55. Esposito, C, Garipoli, V, Di Matteo, G, et al. Laparoscopic management of ovarian cysts in newborns. Surg Endosc. 1998; 12:1152–1154.

56. Meire, HB, Farrord, P, Guha, T. Distinction of benign from malignant ovarian cysts by ultrasound. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1978; 85:893–899.

57. Templeman, C, Fallat, ME, Blinchevsky, A, et al. Noninflammatory ovarian masses in girls and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 96:229–233.

58. De Silva, KS, Kanumakala, S, Grover, SR, et al. Ovarian lesions in children and adolescence—an 11-year review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2004; 17:951–957.

59. Quint, EH, Smith, YR. Ovarian surgery in premenarchal girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1999; 12:27–30.

60. Wu, A, Siegel, MJ. Sonography of pelvic masses in children: Diagnostic predictability. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987; 147:1199–1202.

61. Luxman, D, Cohen, J, David, MP. Laparoscopic conservative removal of ovarian dermoid cysts. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996; 3:409–411.

62. Templeman, CL, Hertweck, SP, Scheetz, JP, et al. The management of mature cystic teratomas in children and adolescents: A retrospective analysis. Hum Reprod. 2000; 15:2669–2672.

63. Kokosa, ER, Keller, MS, Weber, TR. Acute ovarian torsion in children. Am J Surg. 2000; 180:462–465.

64. Servaes, S, Zurakowski, D, Laufer, MR, et al. Sonographic findings of ovarian torsion in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2007; 37:446–451.

65. Shadinger, LL, Andreotti, RF, Kurian, RL. Preoperative sonographic and clinical characteristics as predictors of ovarian torsion. J Ultrasound Med. 2008; 27:7–13.

66. Dolgin, SE, Lubin, M, Shlasko, E. Maximizing ovarian salvage when treating idiopathic adnexal torsion. J Pediatr Surg. 2000; 35:624–628.

67. Laufer, MR, Goitein, L, Bush, M, et al. Prevalence of endometriosis in adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain not responding to conventional therapy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997; 10:199–202.

68. Redwine, DB. Age-related evolution in color appearance of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1987; 48:1062.

69. Martin, DC, Hubert, GD, Vander Zwagg, R, et al. Laparoscopic appearance of peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1989; 51:63–67.

70. Bahamondes, L, Petta, CA, Fernandes, A, et al. Use of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in women with endometriosis, chronic pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea. Contraception. 2007; 75:S134–S139.

71. Patwardhan, S, Nawathe, A, Yates, D, et al. Systematic review of the effects of aromatase inhibitors on pain associated with endometriosis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008; 115:818–822.