CHAPTER 45 Pectoral girdle and upper limb: overview and surface anatomy

This chapter is divided into two sections. The first is an overview of the general organization of the upper limb, with particular emphasis on the distribution of the major blood vessels and lymphatic channels, and of the branches of the brachial plexus: it is intended to complement the detailed regional anatomy described in Chapters 46 to 50 Chapter 47 Chapter 48 Chapter 49 Chapter 50. The second section describes the surface anatomy of the upper limb.

BONES AND JOINTS

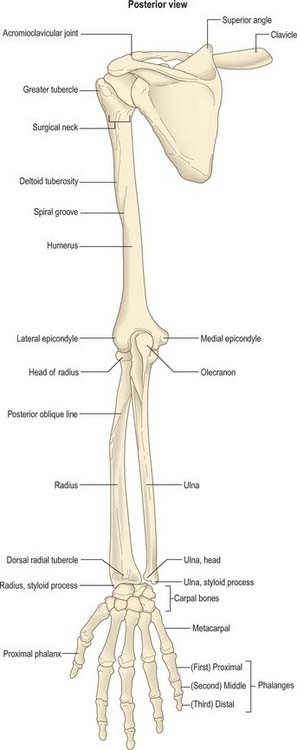

The bones of the upper limb are the clavicle, scapula, humerus, radius and ulna (connected for a large portion of their length by an interosseous membrane) and the bones of the hand, i.e. the carpals, metacarpals and phalanges (Figs 45.1, 45.2).

The shoulder girdle is extremely mobile because reciprocal movements at the sternoclavicular and glenohumeral joints enable 180° abduction of the upper limb. Movement occurs in all three planes at the glenohumeral joint.

MUSCLES

The extensor muscles of the wrist and fingers, together with brachioradialis and a slip of origin of supinator, arise from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. The principal head of pronator teres, the carpal flexor muscles, palmaris longus and, at a deeper level, the main origin of flexor digitorum superficialis, all arise from the medial epicondyle of the humerus. More deeply, flexor pollicis longus, flexor digitorum profundus and pronator quadratus arise from the anterior aspects of the shafts of the radius and ulna and the intervening interosseous membrane. Abductor pollicis longus, extensors pollicis longus and brevis and extensor indicis all arise from the posterior aspects of these bones and the intervening interosseous membrane.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

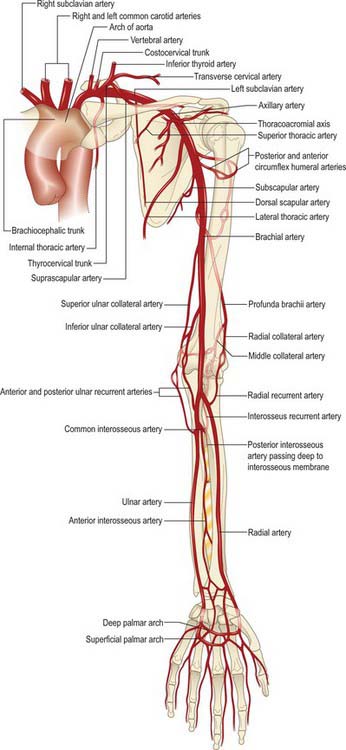

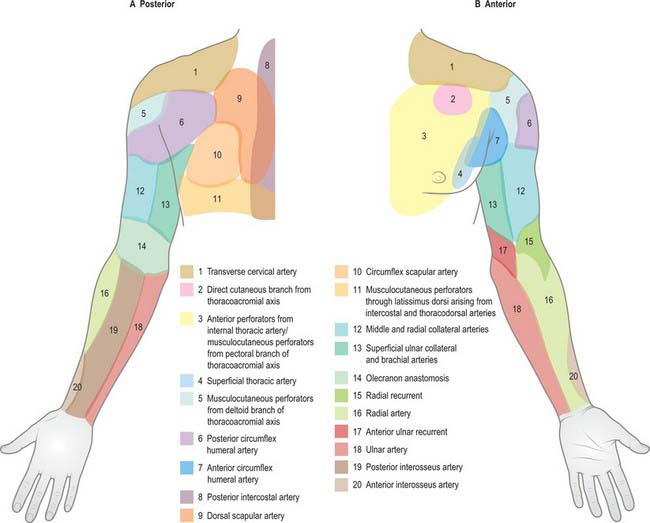

ARTERIAL SUPPLY

The blood supply to the skin of the upper limb comes from a combination of direct cutaneous, fasciocutaneous and musculocutaneous vessels (Figs 45.3, 45.4; see Fig. 7.19).

VENOUS DRAINAGE

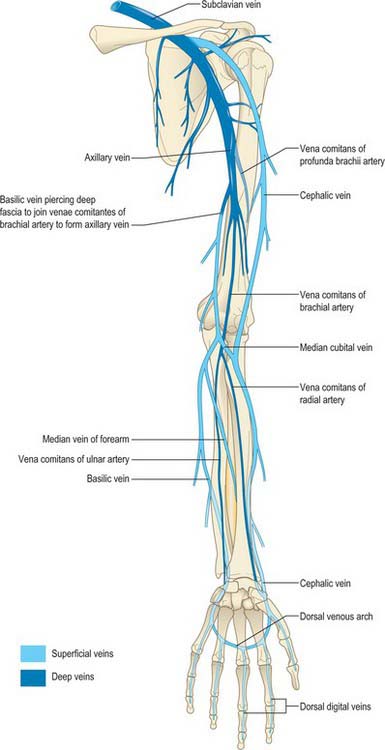

The venous drainage of the upper limb is composed of superficial and deep groups of vessels.

The superficial group starts as an irregular dorsal arch on the back of the hand. The cephalic vein begins at the radial extremity of the arch, ascends along the lateral aspect of the arm within the superficial fascia and then pierces the deep fascia to enter the axillary vein just distal to the clavicle (Fig. 45.5). The basilic vein drains the ulnar end of the arch, passes along the medial aspect of the forearm, pierces the deep fascia at the elbow and joins the venae comitantes of the brachial artery to form the axillary vein. In front of the elbow, the prominent median cubital vein links the cephalic and basilic veins. It receives a number of tributaries from the front of the forearm and gives off the deep median vein which pierces the fascial roof of the antecubital fossa to join the venae comitantes of the brachial artery.

LYMPH NODES AND DRAINAGE

Superficial tissues

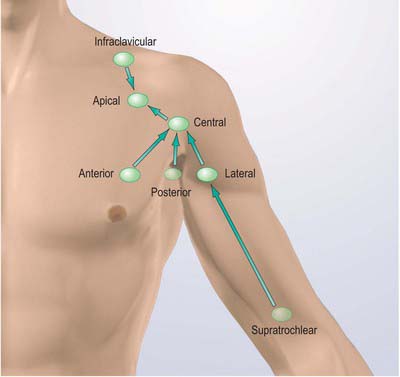

In the forearm and arm, superficial vessels run with the superficial veins. Collecting vessels from the hand pass into the forearm on all carpal aspects. Dorsal vessels, after running proximally in parallel, curve successively round the borders of the limb to join the ventral vessels. Anterior carpal vessels run through the forearm parallel with the median vein of the forearm to the cubital region, then follow the medial border of biceps brachii before piercing the deep fascia at the anterior axillary fold to end in the lateral axillary lymph nodes (Fig. 45.6).

Lymphatic drainage of deep tissues

Deep lymph vessels follow the main neurovascular bundles (radial, ulnar, interosseous and brachial) to the lateral axillary nodes. They are less numerous than the superficial vessels and communicate with them at intervals. A few lymph nodes occur along the vessels. Scapular muscles drain mainly to the subscapular axillary nodes, and pectoral muscles drain mainly to the pectoral, central and apical nodes (Fig. 45.6).

INNERVATION

OVERVIEW OF THE BRACHIAL PLEXUS

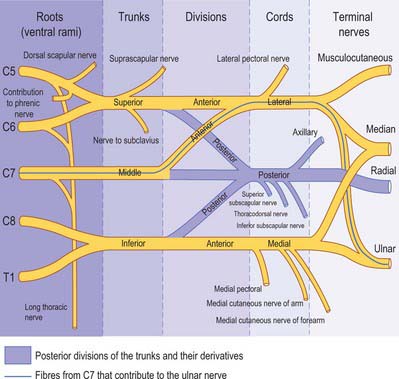

The brachial plexus is formed by the union of the ventral rami of the lower four cervical nerves and the greater part of the first thoracic ventral ramus (Fig. 45.7; see Fig. 46.29).

Fig. 45.7 A schematic plan of the left brachial plexus.

(Adapted from Drake, Vogl and Mitchell 2005.)

The fourth ramus usually gives a branch to the fifth, and the first thoracic ramus frequently receives a branch from the second. These ventral rami are the roots of the plexus: they are almost equal in size but variable in their mode of junction. Contributions to the plexus by C4 and T2 vary. When the branch from C4 is large, that from T2 is frequently absent and the branch from T1 is reduced, forming a ‘prefixed’ type of plexus. If the branch from C4 is small or absent, the contribution from C5 is reduced but that from T1 is larger and there is always a contribution from T2: this arrangement constitutes a ‘postfixed’ type of plexus.

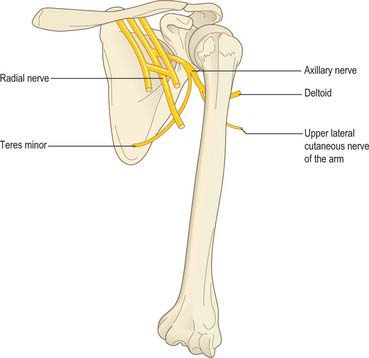

Axillary nerve (C5, 6)

The axillary nerve is a branch of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It winds posteriorly around the neck of the humerus together with the circumflex humeral vessels, and supplies deltoid and teres minor and an area of skin over the deltoid region (Fig. 45.8).

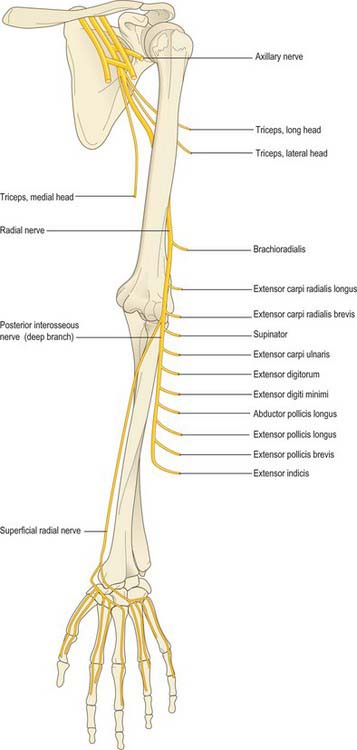

Radial nerve (C5–8, T1)

The radial nerve is the continuation of the posterior cord of the brachial plexus (Fig. 45.9). In the upper arm it lies in the spiral groove of the humerus where it is accompanied by the profunda brachii artery and its venal comitantes. It enters the posterior (extensor) compartment and supplies triceps, then re-enters the anterior compartment of the arm by piercing the lateral intermuscular septum. At the level of the lateral epicondyle it gives off the posterior interosseous nerve, which passes between the two heads of supinator and enters the extensor compartment of the forearm. The posterior interosseous nerve supplies these muscles, while the radial nerve proper continues into the forearm in the anterior compartment deep to brachioradialis and terminates by supplying the skin over the posterior aspect of the thumb, index, middle and radial half of the ring finger.

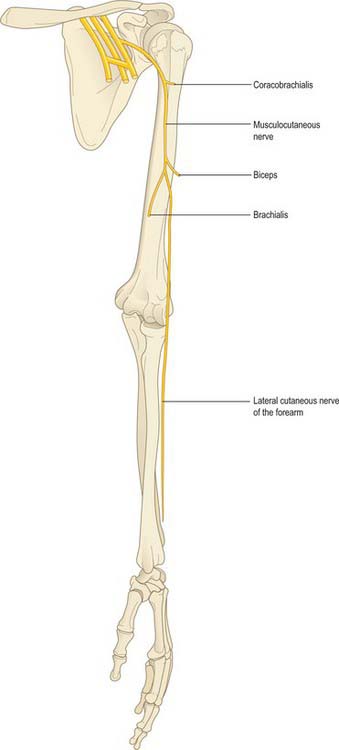

Musculocutaneous nerve (C5–7)

The musculocutaneous nerve is formed from the continuation of the lateral cord of the brachial plexus. It pierces and supplies coracobrachialis, biceps and brachialis, and then continues into the forearm as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm (Fig. 45.10).

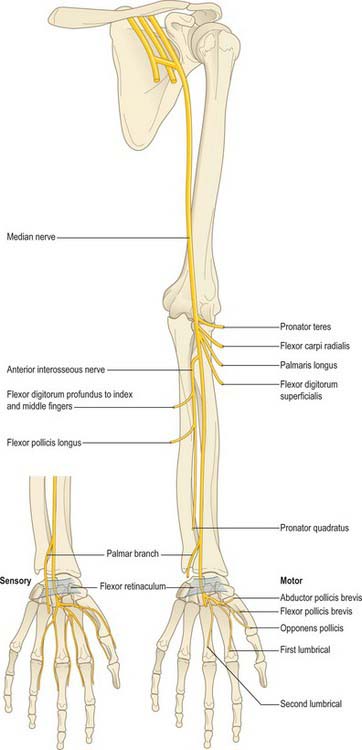

Median nerve (C6–8, T1)

The median nerve is formed by the union of the terminal branch of the lateral and medial cords of the brachial plexus (Fig. 45.11). It has no branches in the upper arm. It enters the forearm between the two heads of pronator teres and gives off the anterior interosseous nerve, which supplies all the flexor muscles of the forearm apart from flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar half of flexor digitorum profundus. The median nerve itself passes deep to the flexor retinaculum at the wrist. On entering the palm, it gives off motor branches to the thenar muscles and the radial two lumbricals, and cutaneous branches to the palmar aspect of the thumb, index and middle fingers and the radial half of the ring finger.

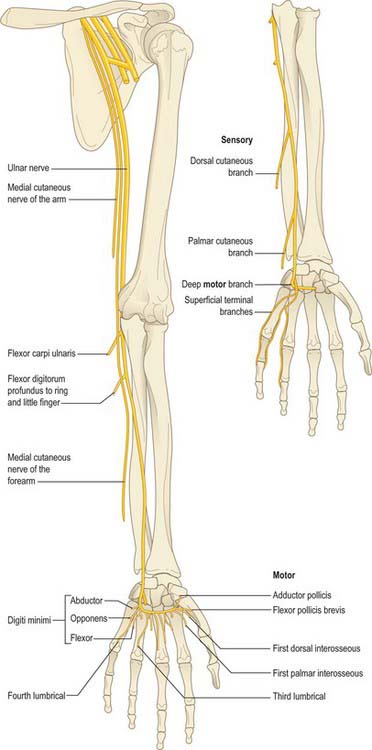

Ulnar nerve (C7, C8, T1)

The ulnar nerve is the continuation of the medial cord of the brachial plexus (Fig. 45.12). Like the median nerve, it has no branches in the upper arm. It enters the posterior compartment of the upper arm midway down its length by piercing the medial intermuscular septum, passes behind the medial epicondyle of the humerus to enter the forearm and descends to the wrist deep to flexor carpi ulnaris. The ulnar nerve supplies flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar half of flexor digitorum profundus. Just proximal to the wrist it gives off a dorsal cutaneous branch that supplies the skin over the dorsal aspect of the little finger and the ulnar half of the ring finger, and then crosses into the palm superficial to the flexor retinaculum in Guyon’s canal. It divides into a motor branch, which supplies the hypothenar muscles, the intrinsic muscles of the hand (apart from the radial two lumbricals) and adductor pollicis, and cutaneous branches, which supply the skin of the palmar aspect of the little finger and the ulnar half of the ring finger.

AUTONOMIC INNERVATION

The autonomic supply to the limbs is exclusively sympathetic. The preganglionic sympathetic inflow to the upper limb is derived from neurones in the lateral horn of the upper thoracic spinal segments T2–6(7). Fibres pass in white rami communicantes to the thoracic sympathetic chain and synapse in the stellate and second thoracic ganglia. Postganglionic fibres to the skin are distributed via cutaneous branches of the brachial plexus. The blood vessels to the upper limb receive their sympathetic supply via adjacent peripheral nerves, thus the median nerve supplies postganglionic sympathetic fibres to the brachial artery and the palmar arches, and the ulnar nerve supplies the ulnar artery.

MOVEMENTS, MUSCLES AND SEGMENTAL INNERVATION

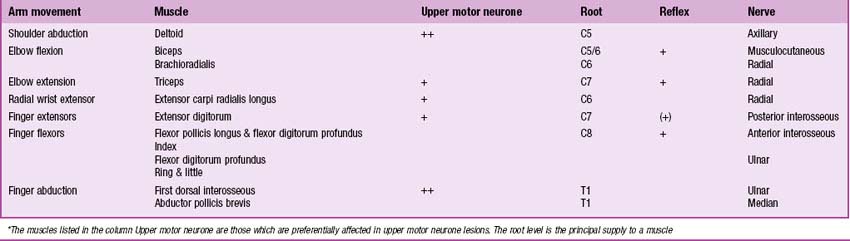

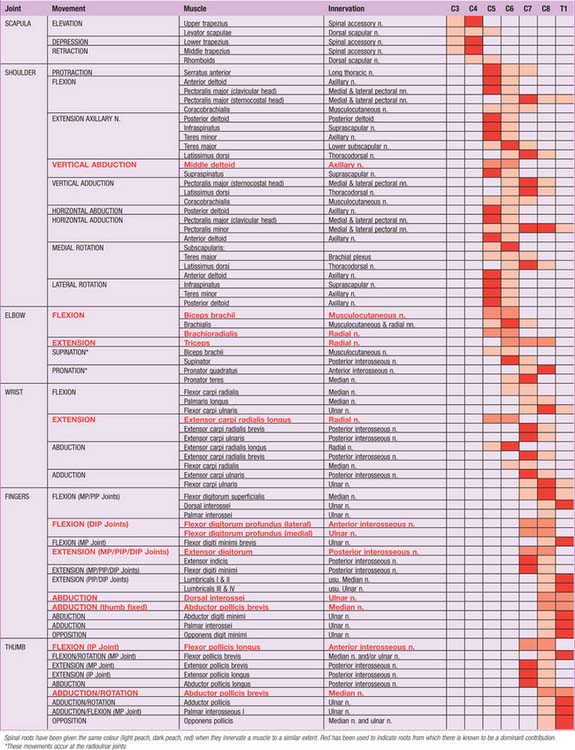

Most limb muscles are innervated by neurones derived from more than one segment of the spinal cord. The predominant segmental origin of the nerve supply for each of the muscles of the upper limb and for the movements which take place at the joints of the upper limb is summarized in Tables 45.1–45.4. Red has been used in Table 45.1 to highlight those muscles or movements which have diagnostic value (see below). The following caveats should be borne in mind when consulting these tables.

Table 45.1 Movements, muscles and segmental innervation in the upper limb. Muscles and movements that have diagnostic value are marked in red

|

Table 45.2 Segmental innervation of the muscles of the upper limb

| C3, 4 | Trapezius, levator scapulae |

| C5 | Rhomboids, deltoids, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, biceps |

| C6 | Serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, subscapularis, teres major, pectoralis major (clavicular head), biceps, coracobrachialis, brachialis, brachioradialis, supinator, extensor carpi radialis longus |

| C7 | Serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major (sternal head), pectoralis minor, triceps, pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, flexor digitorum superficialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi |

| C8 | Pectoralis major (sternal head), pectoralis minor, triceps, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus, flexor carpi ulnaris, extensor carpi ulnaris, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor indicis, abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis |

| T1 | Flexor digitorum profundus, intrinsic muscles of the hand (except abductor pollicis brevis, flexor pollicis brevis, opponens pollicis) |

Table 45.3 Segmental innervation of joint movements of the upper limb

| Shoulder | Abductors and lateral rotators | C5 |

| Adductors and medial rotators | C6–8 | |

| Elbow | Flexors | C5, 6 |

| Extensors | C7, 8 | |

| Forearm | Supinators | C6 |

| Pronators | C7, 8 | |

| Wrist | Flexors and extensors | C6, 7 |

| Digits | Long flexors and extensors | C7, 8 |

| Hand | Intrinsic muscles | C8, T1 |

At the central nervous level of control, muscles are not recognized as individual actuators but as components of movement, and may therefore contribute to several types of movement, acting variously as prime movers, antagonists, fixators or synergists. For example, serratus anterior acts as an antagonist of trapezius as the scapula moves around the thorax, whereas both muscles act together as prime movers during the forward rotation of the scapula. Some muscles have been included in more than one place in Table 45.1, on the basis that a muscle which acts across one joint can produce a combination of movements (e.g. flexion with medial rotation, or extension with adduction) and a muscle which crosses two joints can produce more than one movement. It must also be remembered that these listings are not exhaustive.

There is no universal consensus concerning the contribution that individual spinal roots make to the innervation of individual muscles: the most positive identifications, which are limited, have been obtained by electrically stimulating spinal roots and recording the evoked electromyographic activity in the muscles. Much of the information in Tables 45.1–45.4 is therefore based on neurological experience gained in examining the effects of lesions, and some of it is far from new. In Table 45.1, spinal roots have been given the same colour (light peach, dark peach, red) when they innervate a muscle to a similar extent, or when differences in their contribution have not been described. Red has been used to indicate roots from which there is known to be a dominant contribution. From a clinical viewpoint, some of these roots may be regarded as innervating the muscle almost exclusively, e.g. deltoid by C5, brachioradialis by C6, and triceps by C7. Minor contributions have been retained in the table in order to increase its utility in other contexts, such as electromyography and comparative anatomy.

Neurological location of a lesion

In clinical practice it is only necessary to test a relatively small number of muscles in order to determine the location of a lesion. Any muscle to be tested must satisfy a number of criteria. It should be visible, so that wasting or fasciculation can be observed, and the muscle consistency with contraction can be felt. It should have an isolated action, so that its function can be tested separately. It should help to differentiate between lesions at different levels in the neuraxis and in the peripheral nerve, or between peripheral nerves. It should be tested in such a way that normal can be differentiated from abnormal, so that slight weakness can be detected early with reliability. Some preference should be given to muscles with an easily elicited reflex.

Table 45.4 gives a list of movements and muscles chosen according to these criteria. For example, with an upper motor neurone lesion, shoulder abduction, elbow extension, wrist and finger extension and finger abduction are weaker than their opposing movements. Since this weakness may be more distal than proximal or vice versa, normal shoulder abduction and finger abduction excludes an upper motor neurone weakness of the arm. Some muscles are difficult to test but are included for special reasons, e.g. the strength of brachioradialis is difficult to assess but it can be seen and felt, it is mostly innervated by the C6 root, and it has an easily elicited reflex.

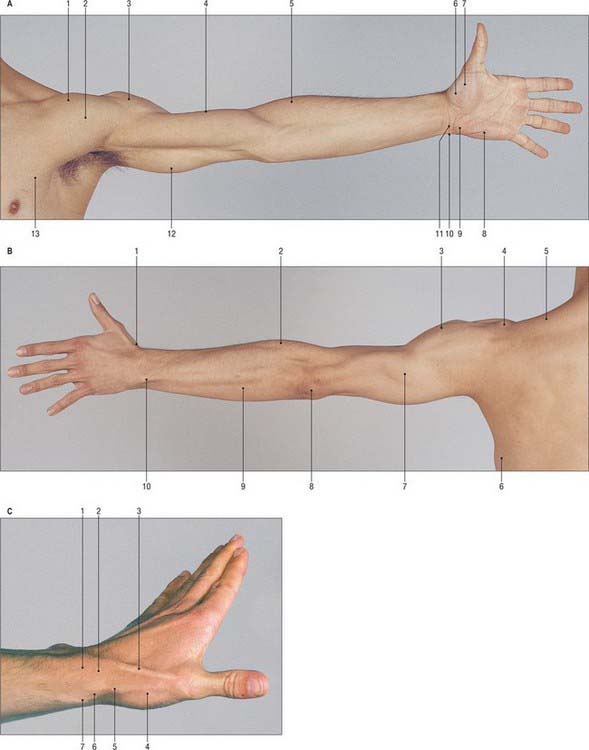

SURFACE ANATOMY

SKELETAL LANDMARKS

A small depression can be seen inferior to the clavicle at the junction of its convex medial and concave lateral portions. This is the infraclavicular fossa (or deltopectoral triangle) and it intervenes between the surface elevations produced by the clavicular origins of pectoralis major and deltoid. The apex of the coracoid process lies 2.5 cm below the clavicle immediately to the lateral side of this fossa, under cover of the anterior fibres of deltoid. If the examining finger is passed laterally from the coracoid process, the lesser tubercle of the humerus will be felt below the tip of the acromion on deep pressure through deltoid. This bony prominence slips away from the examining finger when the humerus is rotated laterally or medially. The greater tubercle of the humerus is the most lateral bony point in the shoulder region and projects laterally below and in front of the acromial angle. It can also be felt to move on rotation of the humerus. When the arm is abducted, the head of the humerus can be palpated on deep pressure in the apex of the axilla.

MUSCULOTENDINOUS LANDMARKS

Proximal to the wrist crease, the prominent tendon of flexor carpi radialis can be seen and palpated when the wrist is flexed; the radial artery lies on its lateral side. By palpating lateral to flexor carpi radialis, 3 or 4 cm proximal to the wrist crease, it is possible to feel flexor pollicis longus (bending and straightening the thumb will confirm that the examining finger is in the correct place). The area on the ulnar side of flexor carpi radialis is packed most densely with functionally important structures. The median nerve lies very close to the skin surface and is therefore often injured in lacerations. It is covered by palmaris longus, when that muscle is present (best confirmed by pinching thumb and ring finger together, when the muscle will be seen to stand out). When palmaris longus is absent, only a thin covering of subcutaneous fat and deep fascia separates skin and nerve. The four tendons of flexor digitorum superficialis lie deep to the median nerve: the tendons for the middle and ring fingers lie in front of those for the index and little fingers as they pass deep to the flexor retinaculum and can be felt, and usually seen, to move on flexion of the fingers. Deeper still are the tendons of flexor digitorum profundus. The large and robust tendon of flexor carpi ulnaris is easily palpated on the ulnar side of the front of the wrist; the ulnar nerve, artery and venae comitantes lie in the shelter of its radial edge. Any sharp injury powerful enough to cut through this strong tendon usually has enough energy left to cut the nerve and vessel.

When the thumb is fully extended, a depression known as the anatomical snuffbox is seen on the lateral aspect of the wrist, immediately distal to the radial styloid process (Fig. 45.13). Palpating distally from the styloid process, three structures are usually encountered: the convex ovoid proximal articular surface of the scaphoid (best felt during alternate ulnar and radial deviation at the wrist); less distinctly, the radial aspect of the trapezium; and the expanded base of the first metacarpal (best felt during circumduction of the thumb). When clinically assessing wrist stability throughout the range of wrist movements, the scaphoid may be effectively compressed bidigitally, between index finger and thumb, along its oblique long axis between tubercle and articular surface. The trapezium may be similarly compressed between its crest and radial aspect.

VESSELS, PULSES AND NERVES

Nerves

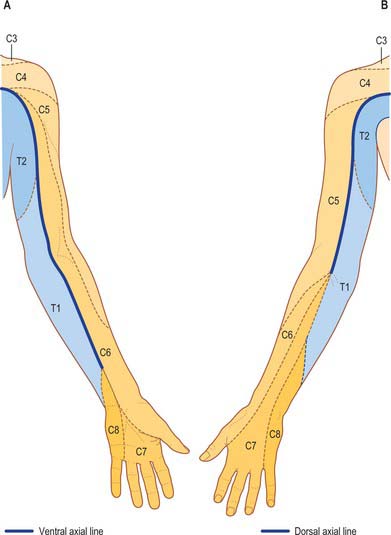

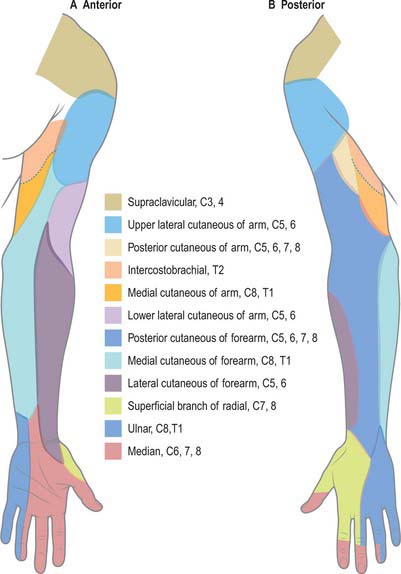

Dermatomes

Our knowledge of the extent of individual dermatomes, especially in the limbs, is largely based on clinical evidence. The dermatomes of the upper limb arise from spinal nerves C5–8 and T1: C7 supplies the central part of the hand (Figs 45.14, 45.15). Considerable overlap exists between adjacent dermatomes innervated by nerves derived from consecutive spinal cord segments.