Chapter 1 Patient safety in body contouring

• Complications of tobacco use are avoidable with a concerted effort by both the patient and the surgeon. Preoperative and postoperative urine cotinine testing make detection of tobacco use straightforward and not reliant on patient self-respect.

• A thorough preoperative assessment should be performed well in advance of the surgical date to allow adequate time for necessary behavior modification (i.e., tobacco cessation), medical modification (improved glycemic control in a diabetic patient), preoperative tests (i.e., sleep study for undiagnosed sleep apnea), and preoperative consultation with appropriate specialists (i.e., hematologist for family history of thrombophilia). Rushing to the operating table can impede a meticulous and safe preoperative investigation.

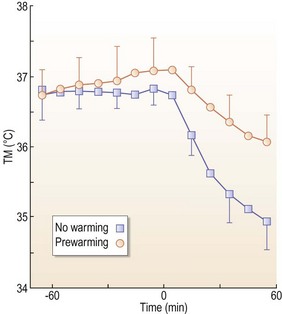

• Hypothermia is a common preventable condition with straightforward preoperative and intraoperative measures such as warm irrigation and preoperative warming blankets. These measures are essential in long body contouring cases with wide exposure.

• Surgical site infections should be prevented at every step, with appropriate preoperative disinfection, perioperative antibiotics, and close glycemic control.

• Thromboembolic events are largely preventable with comprehensive preoperative evaluation and appropriate consultation, mechanical and chemical prophylaxis, patient education, and high levels of alertness and suspicion in the postoperative period.

Introduction

In the end the science of human factors (HF) should be foremost in our minds in designing a system of checks and balances in a given clinical situation.1 A group of well-trained surgeons and health care professionals can still miss a step or two among the hundreds we take from the time the patient enters the clinic for preoperative consultation to the time the patient exits the clinic from the final postoperative visit. In every scenario: the initial consultation, the preoperative assessment, the preop holding area, the operating room, the postoperative care on the wards and in the office, a detail missed can lead to grave consequences. While this chapter is in no way comprehensive, it should aid a surgeon in developing his or her own standardized model for safe clinical practice.

Preoperative Assessment and Patient Selection

Medical Assessment

Cardiac clearance is often a nebulous concept that may get glossed over. Cardiac tests are doled out according to patient age and prior history, and too often, according to institutional guideline. Often a “normal” electrocardiogram tells us very little about the patient. The patient’s functional status should be assessed using exercise tolerance, stress tests, and if deemed appropriate, a cardiology consultation with further noninvasive and invasive studies. All too often, patients are deemed “cleared for surgery” by a physician who is both unfamiliar with the surgical procedure, as well as the duration of recovery and rehabilitation afterwards. Family history is crucially important when a seemingly healthy patient presents to us, since a patient with no apparent cardiac history in the family is a different beast from the patient with three close relatives suffering an early cardiac event. Hypertensive patients should be carefully monitored in the perioperative period because their antihypertensive regimen may have to be changed during periods of fluid shifts, body weight change, and postoperative anemia.2

Patients with significant cardiovascular history deserve special attention. Elective surgery should be delayed until adequate preoperative clearance and tests are attained. If a patient has undergone cardiac intervention, the timing of elective surgery is crucial. Perioperative stent thrombosis is associated with high mortality and morbidity and should not be taken lightly. Patients undergoing noncardiac surgery within 1–2 weeks after placement of a bare-metal stent are at high risk of stent thrombosis and death even if perioperative antiplatelet therapy is continued. Perioperative thrombosis of drug-eluting stents has been reported as late as 21 months after stent implantation. A cardiologist should be consulted to determine both the appropriate surgery date and the appropriate stop date for antiplatelet agents. If elective surgery is pursued too quickly, patients are at risk for stent thrombosis because of increased thrombotic state parlayed by surgery and by the therapeutic absence of antiplatelet agents. In general, elective surgery should be delayed until 6 weeks after balloon angioplasty or bare metal stents, and a year after drug-eluting stents. Patients should be continued on their preoperative beta blockers throughout and post surgery, barring unexpected hypotension.3

Close attention must be paid to the patient’s personal and family history of coagulopathy4 (Tables 1.1 and 1.2). Hereditary thrombophilia is surprisingly common – with approximately 5% of patients displaying factor V Leiden mutation and 2–4% of the population testing positive for antiphospholipid syndrome. Recent data suggest that the family history of a thrombotic event even in the absence of hereditary thrombophilia significantly increases the likelihood that the patient will have a postoperative thromboembolism. In women who smoke, hormone therapies (including oral contraceptives) should ring warning bells, as should a history of multiple miscarriages. Bleeding disorders are rarely life-threatening, but a 2% incidence of Von Willebrand’s in the general population is no small figure. The risk of bleeding should be carefully considered, especially if the patient is about to undergo multiple procedures over large anatomic areas.

| Healthy Subjects | First VTE Episode | |

|---|---|---|

| Antithrombin deficiency | 0.02 | 1 |

| Protein C deficiency | 0.3 | 3 |

| Protein S deficiency | ? | 1–2 |

| Factor V Leiden | 5 | 20–40 |

| Prothrombin gene mutation | 1–2 | 6 |

| Fasting homocysteine >95th % | 5 | 23 |

| Anti-phospholipid antibodies | 3 | 16 |

TABLE 1.2 Indications for a Laboratory Workup for Thrombophilia

Connective tissue diseases are frequently under good medical control when a patient is cleared for surgery. However, connective tissue disorders are independent predictors of thromboembolic events and patients should be informed of this risk factor. Steroids and other immunosuppressants are frequently used in medical management of connective tissue disorders and can place a patient at risk for wound healing complications.5

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a frequently underdiagnosed condition that affects 24% of men and 9% of women. OSA diagnosis can pose a challenge in the preoperative interview because, very frequently, the patients are unaware of the symptoms. Physiologically, the parapharyngeal fat pads narrow the airway, causing restrictive ventilation defects, and resulting in measurable decreases of functional residual capacity and total lung capacity. Of note, over 80% of patients with OSA are undiagnosed, and up to 80% of elderly patients may be affected. Periodic apnea/hypopnea can result in hypertension, arrhythmias, increased intrathoracic negative pressure, and decreased restorative sleep.6

Close preoperative monitoring is especially important in patients with diabetes.7 While the presence of diabetes itself should not preclude surgery, poorly controlled diabetes should halt surgery until better medical management is achieved. HgbA1C is a useful screening tool to check for patient compliance and an index of overall glycemic control, and should be included in the preoperative workup. Even patients who are no longer on insulin will frequently require perioperative insulin to compensate for the stress of surgery as well as diet fluctuations in the postoperative period.

Psychiatric and Behavioral

Second, tobacco impacts wound healing in numerous pathways. Tobacco use reduces cutaneous blood flow in a significant and meaningful way even in light smokers by impairing microvascular vasodilation. Wound healing, immune, and inflammatory responses are blunted in smokers, and collagen deposition and remodeling are decreased. Smoking has been associated with increased wound complications in both aesthetic and reconstructive patients. There is no consensus as to when patients should quit smoking prior to surgery, as benefits of quitting have been found whether a patient quit for 3 weeks, 4–8 weeks, or greater than 2 months. There is no definitive consensus that quitting for a longer period necessarily improves outcome, but the current CDC recommendation is to halt tobacco for 30 days prior to surgery. Self-report of smoking cessation is notoriously unreliable, especially when a patient is incentivized to lie in order to attain the go-ahead for plastic surgery. Objective tests of smoking cessation, such as urine cotinine, may be warranted in order to ensure patient safety.8–14

While tobacco use is a behavior that can be monitored objectively, the plastic surgeon is often faced with a patient who is medically stable, but displays poor judgment, immaturity, unrealistic expectations, or psychiatric illness. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a DSM diagnosis marked by obsession over a perceived defect that results in compulsive behavior and illogical methods to hide or transform the perceived defect. This is most commonly seen in rhinoplasty patients, but is seen with greater frequency than in the general population among cosmetic patients. BDD is a clear psychiatric contraindication for plastic surgery and patients who are suspected of this condition should receive a psychiatric evaluation, not surgery.15

One specific concern for body contouring patients can be the high incidence of maladaptive eating patterns, especially binge eating disorder. In concert with nutritional difficulties presented by the physiology of weight loss, this can lead to poor perioperative nutritional status or weight fluctuations. Psychiatric history should include eating and dieting patterns. Patients with a history of binge eating disorder, in particular, should be carefully assessed to make sure that they have not recently engaged in pathologic eating behaviors.16

Intraoperative Management

Hypothermia has been shown to increase postoperative complications in body contouring patients by inhibiting tissue oxygen delivery, impairing wound healing, and leading to a three-fold increase in wound infections.17

Malignant hyperthermia is a rare but serious complication that has a 70% mortality rate without proper treatment (Box 1.1). The surgeon should be aware of the signs. A thorough preoperative history should ask about family history of sudden death during or after anesthesia. The most consistent sign should be a rapid rise in end tidal CO2, along with high fever, rigidity, acidosis, and tachycardia. The surgery center should always be fully stocked with dantrolene, with the understanding that obese patients require much more dantrolene for symptom reversal than their nonobese counterparts.

Box 1.1

Questions to Ask About Malignant Hyperthermia

Routine Preoperative Questioning

• Is there a family history of MH?

• Have there been unexpected deaths or complications arising from anesthesia (including the dental office) with any family members?

• Is there a personal history of a muscle disorder (e.g., muscle weakness)?

• Is there a personal history of dark or cola-colored urine following anesthesia?

• Is there a personal history of unexplained high fever following surgery?

Intraoperative Preparedness

Planning Ahead

• A written treatment plan should be posted in a conspicuous place. A plan is available from the Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States (MHAUS); http://www.mhaus.org

• A kit or cart containing drugs necessary for the treatment of MH should be immediately available to all operating rooms. Each kit should contain 36 vials of dantrolene, bacteriostatic water for injection, and bicarbonate. MHAUS offers a brochure listing the recommended supplies.

• A refrigerator unit near the operating room should be stocked with iced saline. Ready access to an ice machine is important.

• All operating and recovery room personnel should be trained in the recognition and treatment of MH. Periodic dry-runs of an MH emergency are recommended. In-service materials can be provided by MHAUS.

During Surgery

• Evaluate any unexpected hypercarbia, tachycardia, tachypnea or arrhythmia (e.g., arterial and venous blood gases). Avoid suppressing tachycardia with beta blockers until MH has been ruled out.

• Core temperature should be monitored in all patients given general anesthesia for 30 minutes or more. Acceptable core temperature sites include: distal esophagus, nasopharynx, axilla, rectum, bladder and pulmonary artery. Skin temperature may not adequately reflect core temperature during MH episodes. Consider MH in the differential diagnosis of any temperature rise.

• Stop inhalation anesthetic and succinylcholine if masseter rigidity occurs. If surgery must continue, immediately switch to nontriggering anesthetics.

• Do not give triggering agents to patients with Duchenne dystrophy, central core disease, myotonia and other forms of muscular dystrophy.

• Sudden cardiac arrest in a young male with normal oxygenation should be considered as secondary to hyperkalemia and so treated.

Treating the Known or Suspected MH-Susceptible Patient

Preoperative Preparations:

Intraoperative Considerations

Postoperative Procedure

• If the anesthetic course has been uneventful:

This protocol may not apply to every patient and must of necessity be altered according to specific patient needs.From the MHAUS website www.mhaus.org/

Prevention of surgical site infections is of utmost importance. Preoperative antibiotics should be chosen based on type of organisms encountered, and the patient’s unique infectious disease history. Too frequently, antibiotics are administered as an afterthought after the operation has already begun. Surgical patients should receive antibiotics 30 minutes to 1 hour prior to incision, and before any tourniquet is applied, although this is less relevant in body contouring surgery. Vancomycin and fluoroquinolones take longer to infuse and should be started in the preoperative area, about 2 hours prior to incision time. A study of over 3000 surgical patients found an increased rate of surgical site infections if the antibiotics were administered more than 1 hour prior to incision, at the time of incision, or after the incision was already made. Antibiotics should be re-dosed during lengthy procedures and more frequently if there is significant blood loss (>1.5 L). There is no evidence that shows continuing prophylactic antibiotics beyond 24 hours postoperatively is beneficial. In fact, routine use of postoperative antibiotics increases the likelihood of drug resistance and places the patient at risk for clostridium difficile infections.18,19

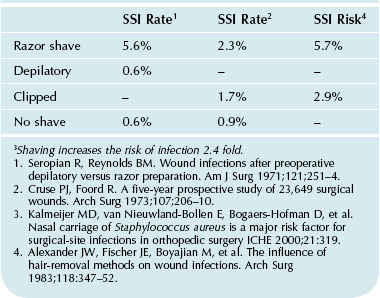

Shaving increases (Table 1.3) the likelihood of surgical site infection (SSI) fourfold. Clipping is less likely to increase surgical site infections, although the risk is not zero. Locally, trauma to the epithelial barrier caused by both shaving and clipping is likely to place the patient at risk for contamination and even infection. Patients should be instructed not to shave the operative site the week prior to surgery.

Staging

There is great debate as to (1) how long is too long and (2) how many procedures are too many. Unfortunately, there is no simple answer. On the plus side, combining procedures is simply more convenient and more cost effective-, for both the patient and the surgeon.20 In a healthy patient who presents a low risk overall, combining procedures is unlikely to lead to serious detriment. However, surgical site infections and thrombotic risk are shown to increase along with the length of operation and these risks should not be taken lightly.

Postoperative Management

Postoperative Antibiotics

SSI is a common adverse event in the plastic surgery patient, and is particularly devastating when the surgery was elective and cosmetic in nature. Plastic surgeons are apt to place patients on antibiotic regimens based upon anecdotal evidence. Large studies have shown no decrease in SSI with postoperative antibiotics. So far, practices such as placing patients on oral antibiotics due to a new implant or while drains are in place have no scientific evidence to support them.21

DVT Prophylaxis

Assessment of thromboembolic risk is the most crucial part of reducing events. However, simple maneuvers should be undertaken (making sure sequential compression devices (SCDs) are in fact on the patient and functioning preoperatively) to continue to reduce risk. Daily rounds should include ensuring the patient has adequate assistance to get out of bed and ambulate in the hallway, and that ambulation is happening as often as can be tolerated. Chemoprophylaxis is frequently indicated, especially in instances where patients are relatively immobile due to postsurgical pain. At this time, there is no evidence that chemoprophylaxis increases the risk of postoperative return to the operating room for a bleeding event. The details of assessing thromboembolic risk and perioperative management will be covered in greater detail in Chapter 4.

Antiplatelet and Beta-blockers

While it is universally agreed that patients should stop certain medications and herbal supplementation that can increase bleeding risk, there is less certainty about medically necessary medications. Antiplatelet agents should not be stopped perioperatively for 1 year after stents, and should be restarted quickly after surgery. If the planned surgery does not require a great deal of undermining, continuing one antiplatelet agent (i.e., hold Plavix but continue aspirin) may be a safe and viable option.3

Beta-blockers should be continued throughout the perioperative period with hold parameters for hypotension.22 Numerous studies and large meta-analyses have shown that beta-blockers are cardioprotective when used in the perioperative period in patients with cardiac risk factors. Beta-blocker therapy appears effective when started several weeks prior to surgery, and long-acting agents appear more successful than short-acting agents. Currently there is no reason to start a beta-blocker for a healthy patient without significant cardiac risk factors.

Glycemic Control

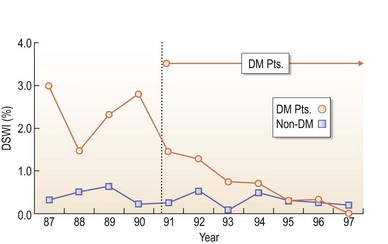

Patients with diabetes are at an increased risk for wound infection due to impaired immunity, microvascular changes and delayed healing mechanisms. Hyperglycemia before and after surgery increases the likelihood of surgical sight infection by three to fourfold. According to Olsen et al, a serum glucose level of greater than 125 before or after surgery parlayed into a more than fourfold increase in surgical site infections.19 In addition, diabetics are also at risk of noninfectious complications including seromas and ischemic necrosis. HgbA1C should have been included in the preoperative workup. The standard diabetic sliding scales would accept glucose levels of 125. Therefore, tight glycemic control (glucose <110) should be the goal of medical protocol postoperatively. If a standard sliding scale is deemed inadequate or the patient has a history of difficult glycemic control, IV insulin and endocrinology consultation should be utilized in the immediate postoperative period.

Postoperative Nausea and Emesis (PONV)

PONV, while not life-threatening, can delay patient clinical course and discharge from hospital care, and can negatively impact patient satisfaction. Risk factors for PONV include female gender, history of motion sickness, history of PONV, preoperative opioids, and nonsmoking (Table 1.4).

The plastic surgery population usually has several risk factors for PONV, and the outcome of PONV can be temporary hypertension and increased risk of bleeding. The best method of PONV prevention appears to be employment of multiple agents. The triple cocktail of Benadryl, dexamethasone, and Zofran appears to be 98% effective in preventing PONV. Emend, an oral agent taken preoperatively, appears to be as effective as IV Zofran and has an effect lasting for 48 hours.23

Patient Safety in Your Practice

A well choreographed preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative clinical regimen should optimize risk reduction. During the first visit, a thorough history should be taken so that any “warnings” in the history can generate a proper workup (Fig. 1.1). While it’s tempting to have the patient obtain medical clearance from his or her internist, additional specialists should weigh in prior to a complex surgery with a long recovery. Age-based preoperative labs and testing may not apply to the massive weight loss population with multiple comorbidities.

Weight loss patients who have recovered from diabetes may need insulin during and briefly after surgery. Glucose should be checked periodically and IV insulin utilized to keep the patient normoglycemic (Fig. 1.2 and Table 1.5). A Foley catheter should be utilized in longer body contouring cases, particularly when large volume liposuction is planned and guidelines for catheter removal followed. Proper padding and gel heel protectors to prevent traction or pressure injury should be used, and all pressure points should be rechecked when patient position is changed during surgery. If the patient is prone, the face should be checked periodically to make sure there is (1) no pressure over the globe and (2) no pressure from the endotracheal tube or tubing against skin surface.

FIG. 1.2 Impact of postoperative glucose control on SSI rates after beginning tight insulin protocol.

From Furnary AP, Zerr KJ, Grunkheimer GL, et al. Continuous intravenous insulin infusion reduces the incidence of deep sternal wound infection in diabetic patients after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:352–62.

| HbA1c Level (%) | Plasma Glucose Level (mg/dL) |

|---|---|

| 6 | 135 |

| 7 | 170 |

| 8 | 205 |

| 9 | 240 |

| 10 | 275 |

| 11 | 310 |

| 12 | 345 |

Maintaining a HbA1c level < 7 is associated with decrease in infectious complications across a variety of surgical procedures.

Odds ratio of 2.13.

95% CI.

P value of 0.007.

From Dronge AS, Perkal MF, Kancir S et al. Long-term glycemic control and postoperative infectious complications. Arch Surg. 2006;141:375–80.

Two hours before the end of surgery, Zofran should be administered for patients at high risk of PONV (Table 1.6). Continuing 80% FiO2 for 2 hours with a nonrebreather face mask can reduce the risk of pulmonary complications. The pneumatic compression devices should be on and continuing to function in the postoperative period.

| Risk Factors | |

Many of our patients have at least 3 risk factors: female gender, nonsmoking, and perioperative opioids.

1 Reason J. Understanding adverse events: human factors. Qual Health Care. 1995;4:80–89.

2 Eagle KimA., Chair., Task Force Members: Raymond J. Gibbons, Elliott M. Antman, Peter B. Berger et al. ACC/AHA Guideline Update for Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery – Executive Summary. Anesthes Analges. 2002;94(5):1052–1064.

3 Grines CL, Bonow RO, Casey DE, et al. Prevention of premature discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery stents. A science advisory from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, American College of Surgeons, and American Dental Association, with representation from the American College of Physicians. Circulation. 2007;115:813–818.

4 Friedman T, Coon DO, Michaels JV, et al. Hereditary coagulopathies: practical diagnosis and management for the plastic surgeon. Plasts Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:1544–1551.

5 Harris EN, Boey ML, Mackworth-Young CG, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies: detection by radioimmunoassay and association with thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Lancet. 1983;322(8361):1211–1214.

6 Jain SS, Dhand R. Perioperative treatment of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10(6):482–488.

7 Jacobers SJ, Sowers JR. An update on perioperative management of diabetes. Arch Int Med. 1999;159:2405–2511.

8 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Smoking and tobacco use: fact sheet. Online. Avaialbe lfrom http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/index.htm (accessed 20 March 2012)

9 Monfrecola G, Riccio G, Savarese C, et al. The acute effect of smoking on cutaneous microcirculation blood flow in habitual smokers and non-smokers. Dermatology. 1998;197:115–118.

10 Manassa EH, Hertl CH, Olbrisch RR. Wound healing and problems in smokers and non-smokers after 132 abdominoplasties. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:2082–2087.

11 Theadom A, Cropley M. Effects of preoperative smoking cessation on the incidence and risk of intraoperative and postoperative complications in adult smokers: a systematic review. Tob Control. 2006;15:352–358.

12 Spear SL, Ducic I, Cuoco F, et al. The effect of smoking on flap and donor-site complications in pedicled TRAM breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1873–1880.

13 Bluman LG, Mosca L, Newan N, et al. Preoperative smoking habits and postoperative pulmonary complications. Chest. 1992;113:883–889.

14 Warner MA, Offord KP, Warner ME, et al. Role of preoperative cessation of smoking and other factors in postoperative pulmonary complications: a blinded prospective study of coronary artery bypass patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:609–616.

15 Sarwer DB. Awareness and identification of body dysmorphic disorder by aesthetic surgeons: Results of a Survey of American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Members. Aesthet Surg J. 2002;22(6):531–535.

16 Kinzl JF, Trefalt E, Fiala M, et al. Psychotherapeutic treatment of morbidly obese patients after gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2002;12(2):292–294.

17 Kurz A, Sessler DI, Lenhardt R. Perioperative normothermia to reduce the incidence of surgical-wound infection and shorten hospitalization. Study of Wound Infection and Temperature Group. New Engl J Med. 1996;334:1209–1216.

18 Classen D, Menlove RL, Burke JP, et al. Surgical site infections. N Engl J Med. 1992;325:281–286.

19 Olsen MA, Nepple JJ, Riew KD, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection following orthopaedic spinal operations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:62–69.

20 Cárdenas-Camarena LMD, González LEMD. Large-volume liposuction and extensive abdominoplasty: a feasible alternative for improving body shape. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 1998;102(5):1698–1707.

21 Perrotti JA, Castor SA, Perez PC, et al. Antibiotic use in aesthetic surgery: a national survey and literature review. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 2002;109(5):1685–1693.

22 Auerbach AD, Goldman L. Beta blockers and reduction of cardiac events in noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 2002;287:1435–1444.

23 Peach MJ, Rucklidge MWM, Lain J, et al. Ondansetron and dexamethasone dose combinations for prophylaxis against postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2007;104(4):808–814.