CHAPTER 5 Patient safety in aesthetic surgery

Much of my inspiration to write and teach about patient safety comes from Lucian Leape MD, my professor of pediatric surgery at the University of Kansas. Dr Leape ultimately left Kansas and went to Harvard School of Public Health, where he focused on patient safety and the ways that mistakes and errors in healthcare delivery could be minimized. Dr Leape was also one of the authors of Crossing the Quality Chasm1 book which defined key quality issues in healthcare delivery. My thinking has been influenced by Steve Spear PhD and Mark Graban, who have gone beyond Dr Leape’s Institute of Medicine book, To Err is Human2 by applying aspects of the Toyota Production System and Lean Manufacturing to healthcare delivery.3,4 While immediate focus has been on how to make the delivery of healthcare safer, there are other widespread defects of dignity, comfort, satisfaction and wasteful allocation of precious resources that will take longer to improve.

The process of patient safety

There are divergent approaches to quality improvement and patient safety in medical care. For individuals who work in hospitals, there is a distinct Joint Commission of the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) “JCAHO-mindset“ regarding policies, processes, and procedures about patient safety that seem to interfere with how surgeons function and how staff thinks that an operating room should function in the real world. For individuals who work in out of hospital environments, including office based surgery units, there seems to be less preoccupation with a “JCAHO boogeyman” and more on how patient safety and care quality can be improved with each patient interaction. Currently, a majority of patient care is rendered in facilities that are outside of a “JCAHO-blessed” workplace. Published reports in the literature substantiate that outcomes are as good or better in out-of-hospital surgical facilities that are accredited by other organizations.5

Too often in the JCAHO, approach to providing solutions for patient safety, important components of safety and quality are overlooked. For instance, the fixation with the “time out” exercise before starting surgery only covers a single dimension of a “surgical destination,” that says what procedure is being performed and the surgical site. What’s missing here is the really important stuff, like a status check of the patient in terms of “being ready for surgery.” I cannot think of a surgeon or the captain of an airliner ready for takeoff who would be angered if a subordinate gave them a status report that covered the requisites of prophylactic antibiotics having been administered, DVT prophylaxis, warming blanket to prevent hypothermia, and the implants that you specified are in the room. Otherwise, the “time out” does not allow for effective communication in a team-oriented workplace.6

Achievement of a superior surgical outcome should always be followed by reflection on what went right and what mistakes were avoided as a means of learning how to repeat such results consistently. Conversely, when failures occur, progress toward improvement is often impeded when we engage in unscientific analysis or resort to naïve investigations, reprisals, and secretive behavior that is often seen in institutions.7

How to create a culture of safety and quality (steps you do with your staff)

1. Identify areas where improvement is needed, i.e. your reoperation rate in breast augmentation.

2. Establish a goal, i.e. making elective surgery safer by lowering the re-operation rate.

3. Defining (map) the process that needs improvement.

4. Develop documents and tools that enable the process to be defined better for patients and staff (Cycle of Care) concept.

5. Minimize mistakes and errors that can occur in the process.

6. Eliminate work-arounds in the process.

7. Measure your progress against benchmark values.

8. Institutionalize your progress and use it as a way to start other quality and safety programs.

Here are some additional thoughts on how to develop a systematic approach to safety:

Delivery of operational excellence requires that work-arounds are eliminated and ambiguities regarding decision areas in planning, care delivery, and patient management. As Steven Spear wrote in his Harvard Business Review article,3 “People confront the same problems, encountered every day, for years, manifested as irritations, inefficiencies, and occasionally catastrophes.” Poor designed systems are set ups for failure and trying harder by working around the problem is not the correct way to solve it. It is only through the efforts of all involved that a better design evolves to avoid defective work or unsafe care. When caregivers are involved in the solution to a problem, there is generally improvement of a process, versus top-down management.

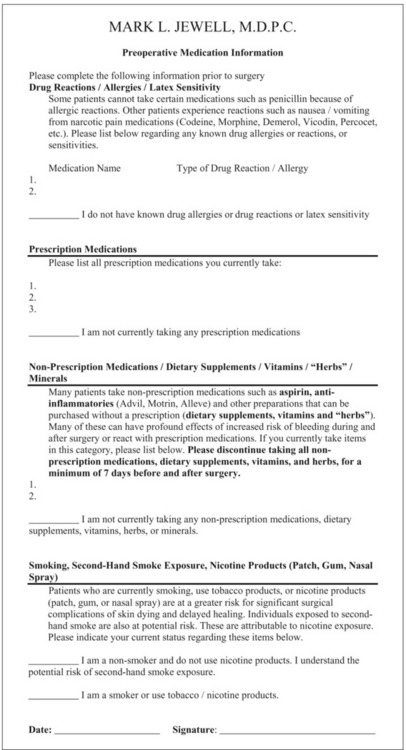

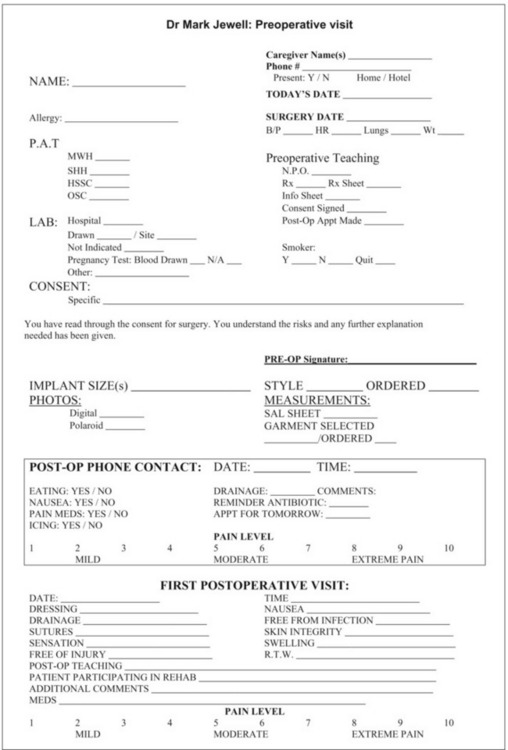

At ASAPS, a dedicated group of physicians, led by James Matas MD, undertook a project to develop the “Cycle of Care” product.8 This was the first time that the entire cycle of care was looked at from the first interaction with a patient until their chart was put back in the record room at the end of the care cycle. By defining a process and the critical inflection points, care could be improved. From an information systems perspective, the amount of information available to make a determination that a patient meets criteria for safe surgery helps make this a simple yes or no decision. Forms and check lists are useful for surgical planning and to document what has been accomplished in preparing for surgery (Box 5.1). Aftercare teaching is equally important regarding wounds, drains, nausea, and danger signs.

The Cycle of Care was envisioned as a “backbone” that could be customized by the end user as a way to lay out the roadmap of what happens during the care of a patient. It is an effective way to help understand what has been accomplished in preparing a patient for surgery and documents the quality of care delivered. This also helps minimize mistakes in planning for surgery, aftercare, and medications (Fig. 5.1).

1. Timely administration of IV antibiotics before surgery.

2. Avoidance of hypothermia during and after surgery.

3. DVT prophylaxis (foot pumps and fractionated heparin).

4. Avoidance of dry eyes during deep sedation or general anesthesia.

5. Effective management of lidocaine-containing wetting solutions along with volumes of lipoaspirate during lipoplasty.

6. Documentation of allergies, currently used prescription and over-the-counter medications, herbal/dietary supplements, and smoking status during the preoperative planning for surgery.

7. Placing the patient at the center of the process by having increased awareness and accountability for their own safety and clinical decisions.

Specific “problematic” topics in patient safety

Methycillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

The matter of MRSA whether community-acquired or hospital-acquired is problematic even in a practice that is oriented towards aesthetic surgery9. It requires a different mindset for all caregivers in terms of meticulous hand washing, use of alcohol or alcohol-chlorhexidine hand sanitizers, protective gloves, disposal of medical waste, and sanitation of the patient care areas and surfaces. MRSA can be brought into the office by something as innocuous as a stitch abscess or impetigo on a child who is accompanying their parent during an office visit. Suspected infections in patients should be cultured and MRSA-effective drugs administered, if a Gram-stain is positive for cocci, pending culture and sensitivities to confirm MRSA.

Smoking and nicotine use

Smoking remains an area of risk in aesthetic surgery. Rees,10 in 1984, described a 13-fold increase in skin necrosis in smokers undergoing rhytidectomy. Other reports show increased risk for other procedures involving flaps. Nicotine remains a very addictive drug, with a high rate of recidivism in those trying to stop its use. I have found it necessary to give patients enough time to successfully stop smoking before surgery of 6 weeks versus shorter periods of time. There still is no consensus on what is the minimum amount of time that a patient has to be 100% smoke-free to be safe from nicotine-induced skin necrosis. It is useful in the preoperative examination to have a patient attest to their smoking and nicotine status. If there is concern regarding compliance, a dipstick urinary continine test can be performed. I have found it helpful not to do the testing on the day or surgery, but two weeks before the scheduled date in order to have time to fill the time, if the test is positive and surgery cannot be performed.11

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

Even in aesthetic surgery, DVT can occur. Reinisch studied DVT during rhytidectomy and noted 84% of the DVT and pulmonary embolisms were associated with general anesthesia.12 The take-home message here is that effective measures such as foot pumps or sequential compression stockings must be used to minimize risk. Chemoprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin, interestingly added the risk of a 16% hematoma complication.13

Abdominoplasty remains a situation with increased morbidity and mortality as compared to other aesthetic procedures. There has been surprisingly no research into why abdominoplasty is 20 times more lethal than lipoplasty.14 DVT prophylaxis, early mobility, and the avoidance of Foley catheters and bedpans appear to be successful in diminishing the risk of complications.15

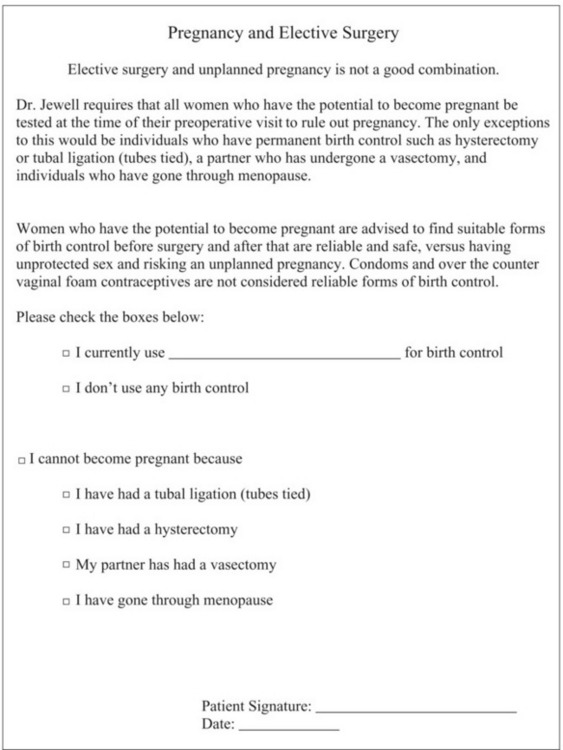

The matter of estrogen supplements and oral contraceptives still lacks consensus regarding management in the perioperative period. If you elect to have a policy on the discontinuation of oral contraceptives by patients undergoing elective surgery on grounds that you are trying to diminish risk of DVT, be certain to recommend alternative forms of birth control.

Lipid emulsions for the treatment of lidocaine/bupivicaine toxicity

The use of Intralipid as a means to resuscitate asystole and CNS toxicity is a novel approach to treat lidocaine and bupivicaine toxicity.16 Additional information may be found at www.lipidrescue.org

Beta-blockers in patients undergoing elective surgery

The use of beta-blockers in patients with documented coronary artery disease has been shown to decrease mortality. While most aesthetic surgery patients are ASA I–II classification, there are individuals that are ASA III, with stabilized systemic disease, hypertension, coronary artery disease, who seek aesthetic and reconstructive procedures. The use of beta-blockers to mitigate perioperative myocardial infarction and arrhythmia is a consideration.17

Plavix®/aspirin withdrawal in patients who have cardiac stents

The use of stent devices for the treatment of coronary artery disease is commonplace. Besides the use of drug-eluting stents to limit restenosis, adjunctive treatment includes anti-platelet drugs such as aspirin and Plavix® (clopidogrel). Decisions to withdraw stent patients from the anti-platelet therapy deserve forethought and discussion with the patient’s cardiologist. Informed consent discussions in stent patients is essential to cover the potential for myocardial infarction and stent occlusion. Late stent thrombosis can occur in situations where patients have completed the recommended 12 months of anti-platelet therapy.18

1. Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm. National Academies Press; July 2001. 337 pp

2. Corrigan J, Kohn L, Donaldson M. To err is human: building a safer health system, 1st edn. National Academies Press; 15 April 2000. 287 pp

3. Spear S. Fixing healthcare from the inside, today. Harvard Business Review. September 2005.

4. Graban M. Lean Hospitals: Improving quality, patient safety, and employee satisfaction, 1st edn, Productivity Press, University Park, IL

5. Jewell M. Medical errors in aesthetic plastic surgery. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2003;23(2):108–109.

6. Keyes G, Singer R, Iverson R, McGuire M, Yates J, Gold, Thompson D. Analysis of outpatient surgery center safety using an internet-based quality improvement and peer review program. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(6):1760–1770.

7. Jewell M. Patient safety data: how it can improve our performance. Aesthet Surg J. 2004;24(4):346–348.

8. The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Cycle of Care Workbook. ASAPS. 2006.

9. Chambers H. Community acquired MRSA-resistance and virulence converge. NEJM. 2005;352:1485–1487.

10. Rees T, Liverett D, Guy C. The effect of cigarette smoking on skin-flap survival in the face lift patient. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1984;73(6):911–915.

11. Jewell M. Smoking in plastic surgery. In: ASPS Patient Consultation Resource Book. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons; 2006.

12. Reinisch J, Bresnick S, Walker J, Rosso R. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus after face lift: a study of incidence and prophylaxis. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(6):1570–1575.

13. Durnig P, Jungwirth W. Low-molecular-weight heparin and postoperative bleeding in rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(2):502–507.

14. Hughes C. Reduction of lipoplasty risks and mortality: An ASAPS survey. Aesthet Surg J. 2001;21:120–127.

15. Stevens WG, Vath S, Stoker D. “Extreme” cosmetic surgery: a retrospective study of morbidity in patients undergoing combined procedures. Aesthet Surg J. 2004;24:314–318.

16. Weinberg G. Lipid rescue resuscitation from local anaesthetic cardiac toxicity. Toxicol Rev. 2006;25(3):139–145. [Review] –

17. Poldermans D, Boermsa E. Beta-blocker therapy in non-cardiac Surgery. NEJM Editorial. 2005;353:412–414.

18. Vaknin-Assa H, Assali A, Ukabi S, Lev EI, Kornowski R. Stent thrombosis following drug-eluting stent implantation. A single-center experience. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2007;8(4):243–247.