Chapter 2 Patient Evaluation and Treatment Algorithms

Introduction

Although the regeneration of true hyaline cartilage is not yet a reality, a variety of methods have the potential to stimulate the formation of a new articular surface, including microfracture of subchondral bone, use of auto- or allografts, cell transplantation, targeted growth factors, and artificial matrices. Reports of the clinical results of these procedures have documented clinical improvement for most of the patients.1,2,3,4 However, despite the availability of all of these techniques and the advances in imaging that have led to an increased understanding of the frequency and types of chondral lesions, patient evaluation and treatment selection still remain challenging. In evaluating a patient for cartilage repair, one must characterize not only the cartilage lesion itself but the various clinical factors and comorbidities embodied by each individual.

Several comorbidities such as ligamentous instability, deficient menisci, or malalignment of the mechanical limb axis or extensor mechanism often coexist with the articular surface pathology. Moreover age-related, nonprogressive, superficial fibrillation of cartilage and focal lesions of the articular surface must be distinguished from degeneration of cartilage occurring as a part of syndrome of osteoarthritis.5 As a consequence, the clinician must define, characterize, and classify local, regional, and systemic, medical, and family history factors that may influence the progression, degeneration, or regeneration of the defect. Careful patient evaluation is essential in selecting the proper treatment plan: lesions with different etiology and size require different treatments and the comorbidities may need to be treated in conjunction with symptomatic chondral injuries to provide a mutually beneficial effect. Thus, the evaluation and characterization of the patient as a whole is key to optimizing the results of surgery.

This chapter provides the guidelines for selecting the proper treatment algorithm.

Clinical Management

The initial step in the workup is the history. This should include mechanism of injury, time course, and quality of symptoms; review of previous treatment; and the effects of those treatments. Peterson et al. found that the average patient presenting for cartilage restoration had 2.1 previous treatments, usually with a different physician.6 In this setting, access to operative reports, pervious imaging, and even direct communication with previously treating surgeons can provide information.

Required radiographs include standing anteroposterior, lateral, patellar skyline, a 45-degree flexion posterior anterior weight-bearing view, and a full-length alignment film. No cartilage restoration procedure should be performed in the setting of malalignment; therefore, if the mechanical axis bisects the affected compartment, a corrective osteotomy should be strongly considered as a concomitant or staged procedure.7,8

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) demonstrate information regarding the regional anisotropic variation of cartilage ultrastructure.9 These advantages provide preoperative information and may allow for a postoperative assessment of actual glycosaminoglycan content of repaired or replaced tissue.10

Local and Regional Facts

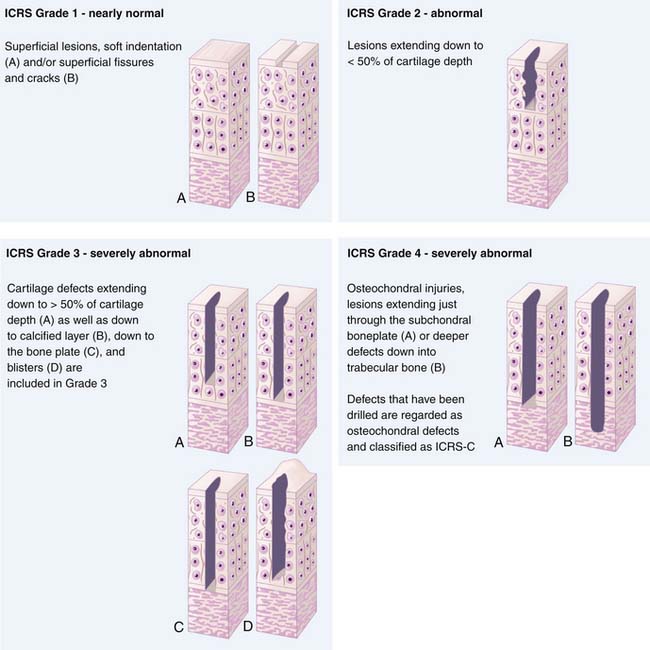

To ensure uniform standards of evaluating articular cartilage repair, a universally accepted classification system is necessary. Many different grading systems for cartilage defects are cited in the literature, including those of Outerbridge,11 Insall,12 Bauer and Jackson,13 and Noyes.14 To avoid confusion, the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) has developed a grading system to be used as a universal language when surgeons are communicating about cartilage lesions. The ICRS characterizes Grade 0 as normal, Grade 1 as superficial lesions and fissures, Grade 2 as lesions extending down to less than 50% of the cartilage depth, and Grade 3 as all lesions extending more than 50% of the cartilage depth and down to bone. Finally, Grade 4 lesions are all that extend down through the subchondral bone plate (Fig. 2-1). This grading system is also included in a comprehensive method of documentation and classification, which encompasses a global description of not only the lesion but all of the local factors and comorbidities previously discussed.15 The following variables are included in the standards:

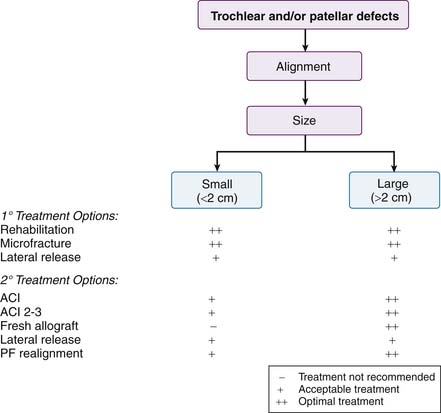

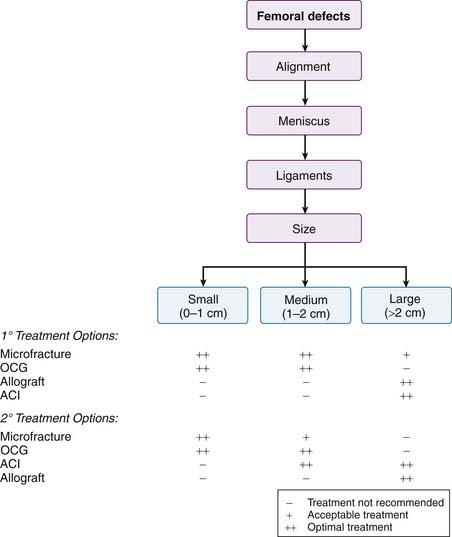

A comprehensive analysis of the local and regional factors related to an articular cartilage lesion is utilized to develop a treatment plan. A flowchart has been created to summarize primary treatment options and secondary treatment options. There are separate charts for femoral and patellar defects. Primary treatment options should be considered first-line treatment choices. Secondary treatment options are considered if primary treatment fails or if other factors prevent the use of a primary treatment option (Figs. 2-2 and 2-3).

FIGURE 2-2 Algorithm for femoral defects. ACI, Autologous chondrocyte implantation; OCG, osteochondral grafts.

Emphasis must again be placed on the importance of looking at the entire picture when characterizing a cartilage lesion. It is imperative to consider each lesion in the context of alignment, ligamentous, and meniscal integrity (macroenvironment), as well as molecular-level factors such as chondrocyte function, synovium, chondropenia, and cartilage integrity (microenvironment).

The Clinical Algorithm: the Chondropenic Pathway

Situation No. 1

Situation No. 3

Situation No. 4

Situation No. 5

Situation No. 6

Situation No. 7

Situation No. 8

Situation No. 9

Situation No. 10

Conclusions and Future Challenges

The challenges of articular cartilage repair and restoration continue despite recent advances. Marrow stimulation techniques, substitution replacement options, and biological replacement options each have a role in the treatment algorithm of articular cartilage defects. This treatment algorithm must take into account not only the characterization of the specific cartilage lesion but also the myriad of local and regional factors as well as the comorbidities attached to each patient. As of yet no single treatment option can reestablish the hyaline cartilage seen in normal articular cartilage. The goal for future treatments is to develop new technologies and disease-modifying interventions that protect and preserve the joint over time by maintaining biochemical, biomechanical, and cellular integrity. Until these technologies exist, collaboration between the basic scientist and the clinician will continue to advance our current technologies in an effort to restore the violated articular cartilage surface.

1. Mithoefer K., McAdams T.R., Scopp J.M., Mandelbaum B.R. Emerging options for treatment of articular cartilage injury in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2009 Jan;28(1):25-40.

2. Brittberg M., Peterson L., Sjögren-Jansson E., Tallheden T., Lindahl A. Articular cartilage engineering with autologous chondrocyte transplantation: a review of recent developments. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(suppl 3):109-115.

3. Steadman J.R., Briggs K.K., Rodrigo J.J., Kocher M.S., Gill T.J., Rodkey W.G. Outcomes of microfracture for traumatic chondral defects of the knee: average 11-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:477-484.

4. Kon E., Delcogliano M., Filardo G., Montaperto C., Marcacci M. Second generation issues in cartilage repair. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008 Dec;16(4):221-229.

5. Buckwalter J.A., Mankin H.J., Grodzinsky A.J. Articular cartilage and osteoarthritis. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:465-480.

6. Peterson L., Minas T., Brittberg M., Lindahl A. Treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation: results at two to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(suppl 2):17-24.

7. Alford J.W., Cole B.J. Cartilage restoration, part 1: basic science, historical perspective, patient evaluation, and treatment options. Am J Sports Med. 2005 Feb;33(2):295-306.

8. Alford J.W., Cole B.J. Cartilage restoration, part 2: techniques, outcomes, and future directions. Am J Sports Med. 2005 Mar;33(3):443-460.

9. Potter H.G., Black B.R. Chong le R. New techniques in articular cartilage imaging. Clin Sports Med. 2009 Jan;28(1):77-94.

10. Welsch G.H., Mamisch T.C., Quirbach S., Zak L., Marlovits S., Trattnig S. Evaluation and comparison of cartilage repair tissue of the patella and medial femoral condyle by using morphological MRI and biochemical zonal T2 mapping. Eur Radiol. 2009 May;19(5):1253-1262.

11. Outerbridge R.E. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:752-759.

12. Insall J. Current concepts review: patellar pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:147-152.

13. Bauer M., Jackson R.W. Chondral lesions of the femoral condyles: a system of arthroscopic classification. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:97-102.

14. Noyes F.R., Bassett R.W., Grood E.S., Butler D.L. Arthroscopy in acute traumatic hemarthrosis of the knee: incidence of anterior cruciate tears and other injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:687-695. 757

15. International Cartilage Repair Society. The cartilage standard evaluation form/knee. ICRS Newsletter. 1998;1:5-7.