Patient Education

According to the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, patient/client-related instruction is one of the three major components of physical therapist intervention.1In cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapy, choosing an effective procedural intervention is based on the physiological evaluation of the patient. Similarly, choosing effective patient instruction or education methods is based on the learning needs assessment of the patient.2 The overall goal of patient education is for the patient to practice health behaviors that promote health, well-being, and independence in self-care. Cardiovascular and pulmonary patient education can pose a significant challenge to the physical therapist. Patient education interventions can range from teaching a hospitalized patient about cardiac risk factor modification to designing a series of community-based exercise classes for children with asthma. Meeting this challenge is important because the benefits of patient education include reduced health-care costs, reduced disability, enhanced patient decision making, improved patient knowledge, and increased quality of life. In addition, physical therapists share with other health-care providers the responsibility of ensuring that patients have the opportunity to make informed choices in their care. Unless effective patient education is implemented, this opportunity will be lost.

Defining Patient Education

Physical therapists believe that patient education is an important part of patient care.3 The teaching role of the physical therapist has been reported as highly valued by patients as well.4 According to the Consumer and Patient Health Information Section of the Medical Library Association (1996),5 patient education is “a planned activity, initiated by a health professional, whose aim is to impart knowledge, attitudes and skills with the specific goal of changing behavior, increasing compliance with therapy and, thereby, improving health.”5

Objectives

The overall objective of patient education is to effect a durable cognitive improvement that results in a positive change in an individual’s or group’s health behavior. In most cases the physical therapist must embark on a process to meet this objective in the course of procedural interventions. The education process consists of assessing the learning needs of the patient, identifying measurable, realistic objectives, planning and implementing the patient education program, and finally, evaluating its effectiveness. Specific examples of patient education learning objectives are listed in Box 28-1.

Achieving these objectives will lead to the achievement of a host of documented benefits of patient education. These include reduced length of hospital stay,6 reduced patient anxiety,7 improved health-related knowledge,8 increased quality of life,9 and improved response and adherence to medical treatment.10 Patient education has also been shown to empower patients to take more active roles in their health care.11 Patients who are educated partners in their care are able to be smart consumers in the health-care system and adapt more readily to the changes in their lifestyles that result from illness. Educated patients learn and understand the health consequences of their behaviors and choices.

Learning Theory: Concepts Pertinent to Cardiopulmonary Patient Education

The social-cognitive theory as developed by Bandura (1986)12 posits that human behavior can be explained and predicted using the following key regulators: incentives, outcome expectations, and efficacy expectations. For example, a myocardial infarction patient perceives value in following the exercise program (incentive). Patients with this incentive will attempt to exercise if they believe that their current sedentary lifestyle poses a threat to health. These patients also believe exercise will reduce that threat (outcome expectation) and that they are personally capable of performing the exercise program (efficacy expectation). Outcome and efficacy expectations directly relate to patients’ beliefs about their capabilities and the relationship of their behaviors to successful outcomes. In essence, then, behavior is influenced by perceptions that create expectations for similar outcomes over time.

To function competently in a given environment requires a belief in one’s ability to attain a certain level of performance. Bandura terms this self-efficacy.13 He argues that perceived self-efficacy influences all aspects of behavior, including learning new skills and inhibiting or stopping current behaviors. Self-efficacy has the following four primary determinants:

1. Performance accomplishments, which is the strongest determinant and refers to “acting out” the desired behavior and mastering the task, resulting in increased self-efficacy

2. Vicarious experience, which involves learning through observing the actions of others, especially actions with clear, rewarding outcomes

4. One’s physiological state as it relates to the perceived ability to perform a given task

The health-belief model, developed in the early 1950s, theorizes that patients are likely to take a health action in the following situations: they believe they are at risk for illness; they believe that the disease poses a serious threat to their lives should they contract it; they desire to avoid illness and believe that certain actions will prevent or reduce the severity of the illness; and they believe that taking the health action is less threatening than the illness itself.14 This model was originally developed in an attempt to understand why large numbers of people failed to accept preventative care or screening tests for early disease detection. Subsequent studies have used the model to analyze compliance with regimes for hypertension, asthma, and diabetes.15 The health-belief model conveys that in the context of health behavior some stimulus or “cue to action” is necessary to initiate the decision-making process. These cues can be internal (i.e., a productive cough) or external (i.e., instructional video on pulmonary hygiene techniques). Once the behavior commences, it is understood that many demographic, structural, personal, and social elements are capable of influencing the behavior. In addition, perceived barriers (i.e., unpleasant side effects) may limit or prevent undertaking the recommended behavior.

The behavior-modification approach has its roots in operant-learning theory and consists of techniques that manipulate environmental rewards and punishments in relationship to a specified behavior.16 The theme of this approach is that an individual’s behavior can gradually be shaped to meet a set objective. According to Becker (1990),17 the behavior-modification approach frequently follows a general plan: “identify the problem; describe the problem in behavioral terms; select a target behavior that is measurable; identify the antecedents and consequences of the behavior; set behavioral objectives; devise and implement a behavior change program; and evaluate the program.”17 This plan is similar to the patient/client management model1 that physical therapists use to achieve optimal patient care outcomes. The physical therapist examines the patient, describes the problem(s) in functional terms (evaluation and diagnosis), sets short-term and long-term functional goals, designs a plan of care to meet those goals (prognosis), implements the plan (intervention), and reevaluates the patient. These similarities may facilitate the use of the behavioral-modification approach by physical therapists.

Health-care contracts can be useful in implementing the behavior-modification approach. An example of such a contract may be seen in Box 28-2. The contract should be realistic, measurable, and renewable.18 Specific goals, time frames, behaviors, and contingencies are written in the contract. The clinician and patient discuss and then sign the contract. Positive and negative reinforcements are used to facilitate the desired behaviors in the patient. Ideally, once the contract expires, the patient feels competent and is able to continue the desired behaviors without the external reinforcements.

Needs-Based Approach to Patient Education

The most important aspect of planning for patient education is assessing the learner. The process of patient education requires assessment of the total patient and family, including an understanding of the psychosocial, socioeconomic, educational, vocational, and cultural qualities of the patient and family unit.19 Assessing educational needs of the patient allows the physical therapist to determine what the patient needs to know to meet the desired cognitive and behavioral teaching objectives. This assessment also increases patient-teacher rapport and allows the physical therapist to individualize the learning experience.

Learning Needs Assessment

Tools

The American Physical Therapy Association’s Commission on Accreditation of Physical Therapy Education in their Normative Model of Physical Therapist Professional Education: Version 200420 requires that the graduate physical therapist be able to “effectively educate others using culturally appropriate teaching methods that are commensurate with the needs of the learner.”20 Learning needs can be assessed in a variety of ways. These include patient and family interviews, questionnaires and surveys, written tests, and observation of patient performance.21 Interviews allow the physical therapist to ask questions directed at determining the patient’s view of the illness, including associated beliefs and attitudes. Questionnaires and surveys can be used in conjunction with the interview to document the patient’s responses to specific questions about his or her condition. Open-ended questions such as “What are the major problems your illness has caused for you and your family?” elicit more information than a multiple-choice format. Written tests can be helpful in determining what patients already know when the tests are given, before any teaching. These tests can also identify problems with reading, comprehension skill, and health literacy. Observing patients as they perform a skill, such as diaphragmatic breathing, reveals whether the patient can demonstrate the correct technique. The physical therapist can also pose questions to the patient during the demonstration to determine whether the patient knows the rationale for the exercise.

Areas to Assess

The learning needs assessment encompasses the following five major areas: perceptual, cognitive, motor, affective, and environmental (Box 28-3). By addressing these five areas, the physical therapist will obtain an accurate picture of the patient’s learning abilities, knowledge level, performance skills, attitudes, and cultural influences.

All five of these areas can be addressed with the use of a learning needs assessment survey (Box 28-4). By using a survey in combination with the physical therapy patient evaluation, the therapist can gather all the necessary information to create an optimal patient education experience. The survey in Box 28-4 consists of three parts, which can be adapted to any patient care setting. In the pediatric setting, some of the questions could be asked of the parent(s) or rephrased to address school-age children. Part I primarily assesses the patient’s perception of the illness or disability and its impact on the patient’s life. Part II lists a wide variety of teaching methods and asks the patient to indicate which methods he or she personally feels are most useful. Part III identifies specific topics about which the patient would like to know more. This part is also helpful in alerting the therapist that referrals to other members of the interprofessional health-care team may be required. For example, if the patient selects “I would like to know more about what I should eat,” the therapist would make a referral to the dietitian. Patients’ answers provide clues to learning style preferences that work best for them and can often provide clues to health literacy issues.

Health Literacy

Certain barriers, such as limited health literacy, can alter the effectiveness of patient education and rehabilitation interventions, such as promoting lifestyle behavior changes.22,23 Health literacy can be described as a person’s ability to comprehend health information and use that information to make informed decisions about his or her health and medical care.24 Specifically, the patient needs these skills when reading consent forms, prescription drug information, food labels, rehabilitation instructions, and appointment slips or when filling out a health insurance form or reviewing a health care bill.25–27 Health literacy is required to read a peak flow meter, to understand body mass index (BMI), and to recognize whethera blood pressure reading is considered high.28 Signs of limited health literacy can be found in Box 28-5. Limited health literacy increases the risk for hospitalization, the overall cost of health care, and mortality rates. Studies have shown that patients with limited health literacy are more likely to report difficulties with activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) as a result of poor or diminished physical health and pain that interferes with normal work activities.29 Those with limited health literacy also have higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, depressive symptoms, and physical limitations. Older adults with limited health literacy also may demonstrate a higher incidence of heart failure, arthritis, and multiple health conditions, and they tend to have a greater need for complex medical management.29,30 Patients with limited health literacy have less knowledge about hypertension, diabetes, and asthma.25 Inadequate health literacy skills are key factors in the exacerbation of heart failure.31

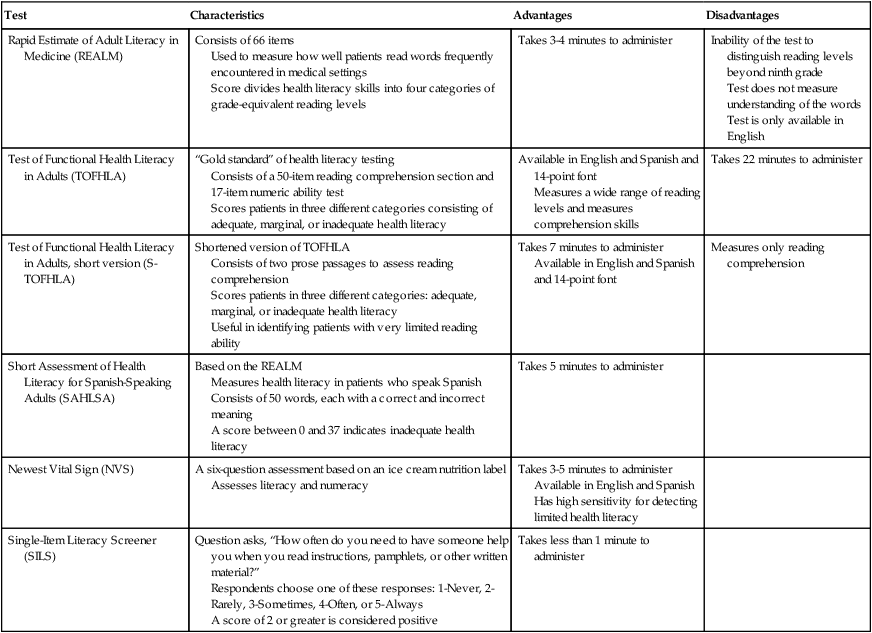

Health literacy is also linked to improved compliance with a physical therapy plan of care and ultimately leads to better health and medical care outcomes.32 Current cardiovascular and pulmonary research demonstrates that patients with adequate health literacy are more likely to keep records of their blood glucose test results33 and demonstrate improved medication compliance with a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease.34 Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who receive and understand self-management education have decreased hospital admissions.35 Although outside the scope of this chapter, certain formal assessment tools can be used to determine an adult patient’s health literacy level (Table 28-1).

Table 28-1

Health Literacy Screening and Assessment Tools

| Test | Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) | Consists of 66 items Used to measure how well patients read words frequently encountered in medical settings Score divides health literacy skills into four categories of grade-equivalent reading levels |

Takes 3-4 minutes to administer | Inability of the test to distinguish reading levels beyond ninth grade Test does not measure understanding of the words Test is only available in English |

| Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) | “Gold standard” of health literacy testing Consists of a 50-item reading comprehension section and 17-item numeric ability test Scores patients in three different categories consisting of adequate, marginal, or inadequate health literacy |

Available in English and Spanish and 14-point font Measures a wide range of reading levels and measures comprehension skills |

Takes 22 minutes to administer |

| Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults, short version (S-TOFHLA) | Shortened version of TOFHLA Consists of two prose passages to assess reading comprehension Scores patients in three different categories: adequate, marginal, or inadequate health literacy Useful in identifying patients with very limited reading ability |

Takes 7 minutes to administer Available in English and Spanish and 14-point font |

Measures only reading comprehension |

| Short Assessment of Health Literacy for Spanish-Speaking Adults (SAHLSA) | Based on the REALM Measures health literacy in patients who speak Spanish Consists of 50 words, each with a correct and incorrect meaning A score between 0 and 37 indicates inadequate health literacy |

Takes 5 minutes to administer | |

| Newest Vital Sign (NVS) | A six-question assessment based on an ice cream nutrition label Assesses literacy and numeracy |

Takes 3-5 minutes to administer Available in English and Spanish Has high sensitivity for detecting limited health literacy |

|

| Single-Item Literacy Screener (SILS) | Question asks, “How often do you need to have someone help you when you read instructions, pamphlets, or other written material?” Respondents choose one of these responses: 1-Never, 2-Rarely, 3-Sometimes, 4-Often, or 5-Always A score of 2 or greater is considered positive |

Takes less than 1 minute to administer |

From Cutilli CC: Do your patients understand? OrthopNurs 24(5):372–377, 2005; Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al: Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: A shortened screening instrument, Fam Med 25(6):391–395, 1993; Mancuso JM: Assessment and measurement of health literacy: An integrative review of the literature, Nurs Health Sci 11:77–89, 2009; Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, et al: The test of functional health literacy in adults: Anew instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills, J Gen Int Med 10(10):537–541, 1995; Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, et al: Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy, Patient Educ Couns 38(1):33–42, 1999; Lee SY, Bender DE, Ruiz RE, et al: Development of an easy-to-use Spanish health literacy test, Health Serv Res 41(4 Pt 1):1392–1412, 2006; Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al: Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign, Ann Fam Med 3:514–522, 2005; Pfizer: The newest vital sign: Anew health literacy assessment tool for health care providers. Available at: http://www.pfizerhealthliteracy.com/physicians-providers/NewestVitalSign.aspx; and Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, et al: The single-item literacy screener: Evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability, BMC Fam Pract 7(1):21, 2006.

Formulation and Prioritization of Goals

Prioritizing the patient’s educational goals in conjunction with other intervention goals enhances the therapist’s efficiency. Referring again to the learning needs assessment survey (see Box 28-4) to determine what knowledge is important to the patient will guide the therapist in creating the most appropriate prioritization of goals. Simplicity is usually best. Overwhelming patients with a huge list of items to be accomplished may discourage them before they even start. If the patient’s learning needs are great, start by breaking down the list of goals into smaller groups. Choose the most important goals and try to accomplish those first. If you run into a series of failures, tackle the next group. Build on each success the patient experiences.

Educational Methods

Method Selection

In addition to considering the level of health literacy of the patient and the caregiver, using the learning needs assessment survey (see Box 28-4) will allow the clinician to choose education methods that will facilitate optimal learning in a given patient or group. The patient(s) can self-select the available learning methods that have the greatest learning potential. A combination of methods may be necessary to achieve the educational goals that have been set. If a patient is not sure which methods to indicate, the therapist can base the choice on the other information provided in the survey (e.g., sensory deficits, health literacy level, or type of information desired).

One way to determine learning styles without completing a survey is to ask patients (or their caregiver) about any hobbies and how they became proficient with the hobby. For example, did they read about it, watch a video, or take a class to learn about the hobby?32 Surveys generally require regular updates to ensure that all of the offered methods are listed and that any discontinued methods are removed from the list. In addition, the physical therapist should assess potential learning materials for readability, age-appropriateness, accuracy of content, intended audience, and clarity.19 Recently, even the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the American Heart Association (AHA) had their written materials reviewed for things such as reading level, word usage, clear and specific behavioral recommendations, etc.36 Please see Box 28-6 for guidelines for creating patient education materials, as well as Box 28-7 for resources for developing and assessing readability of printed patient education materials.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Each education method has its own advantages and disadvantages. Table 28-2 lists the key advantages and disadvantages of 13 education methods. The table is designed to assist the physical therapist in determining the settings and populations in which the methods will be most useful. However, this is not a comprehensive list. In fact, some health education challenges require truly innovative approaches.

Table 28-2

Comparison Chart for Education Methods (Adults and Children Unless Otherwise Noted)

| Type | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Reading | Patient can refer back to material. Low effort for instructor. | Requires instructor follow-up for comprehension. |

| Lecture | Time-efficient for instructor. Cost-efficient. | Low interaction. May pacify rather than engage. |

| Demonstration | Adds sensory data to learning. Allows for problem solving and modification. | Instructor needs proficiency in the skill being taught. |

| Video | Access to restricted areas. Portrays events that are infrequent, costly, and difficult to reproduce. Portable. | Noninteractive. May pacify rather than engage. Requires costly electronic equipment. Difficult to control quality. |

| Audiotape | Portable. Useful for sight-impaired learner. | Requires electronic equipment. |

| Group discussion | Effective use of instructor time. Enlarges pool of real-life experiences. Nonthreatening to some learners. Mutual support possible. | Not as much individual attention given. Group may be hard to control (e.g., too talkative, shy, hostile). Strong facilitator skills needed. |

| Clubs, camps, and retreats | Draws on community and individual resources. Needs less professional input and time. | Same as above. Some risk for perpetuating myths and false information. |

| Individual instruction | Instructor can tailor learning to student’s needs and desires. More one-on-one time. | Inefficient use of instructor time. Limited pool of experience on which to draw. |

| Games and directed activities | Helpful for children. Reduces anxiety. Uses repetition. Fun. Unexpected experiences can lead to new understandings or insights. | May be difficult to schedule space and find participants. |

| Computer programs | Interactive, self-paced. Large information capacity. Time-efficient for instructor. | Expensive. Special equipment and space needed. May require expert help. |

| Seminars and workshops | Diversity of instructors and formats. Pool of experts and community resources. Can tailor content broadly or narrowly. | Expensive. May cause scheduling and space problems. |

| Role-playing | Allows trial runs, problem-solving, simulated experiences. | Threatening to some. Can be time-consuming. Instructor needs to be skilled in techniques and in dealing with effects on participants. |

| Oral and written tests | Can provide instructor with evidence of what learner needs to be taught and what has been learned. | Literacy and supplies required, if written. May be time-consuming. |

Content

The specific content of patient education materials and programs should be determined by the needs of the individual or group being taught. There are, however, topics common to many cardiovascular and pulmonary education efforts. These topics are listed in Box 28-8. The physical therapist can use these topics as a checklist to explore the content covered (or to be covered) in a given cardiopulmonary education experience. Although physical therapists may not be responsible for teaching on all these topics, they should be familiar with all the topics taught by the healthcare team. Educational materials on all of these topics have already been developed by a variety of healthcare providers, educators, and organizations and may be available for use by physical therapists (see Interprofessional Considerations and Resources, later in this chapter).

Determination of Effectiveness

Presenting information in visual form, for example, using pictorial aids and videos, has been recommended37for patients diagnosed with COPD who are identified as having limited health literacy. For patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, an interactive, computer-based information program is suggested.38 Patient education for patients with coronary heart disease should be “multi-faceted and interprofessional.”39

Teacher-Learner Relationship

According to Locke (1986),40 the primary step to understanding others is an awareness of one’s self. Acknowledging one’s own personal values, interests, and biases will significantly increase one’s sensitivity toward others. The skilled teacher is aware of his or her own communication style and its limitations and can convey the desire to help despite those limitations.

The teacher-learner relationship that develops between physical therapist and patient is largely the result of communication between the two in the context of culture. Communication is a two-way process consisting of verbal and nonverbal messages. The interpretation of these messages depends on the cultural cues operating in the educational setting. Fairchild (1970)41 defines culture as all social behavior, such as customs, techniques, beliefs, organizations, and regard for material objects, including behaviors transmitted by way of symbols. According to Locke (1992), “the primary mode of transmission of culture is language, which enables people to learn, experience, and share their traditions and customs.”42In addition, culture can be expressed or experienced via economic and political practices, art, and religion. Health care and medicine have their own cultures. To meet the needs of culturally diverse populations and engage in positive, productive relationships, physical therapists must operate from a framework of cross-cultural understanding. This understanding and knowledge can then be reflected in patient education efforts.

Communication

Patients with cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, such as congestive heart failure, are not always comfortable communicating with health-care professionals or questioning the physician’s decisions. In Circulation (2009),43 the American Heart Association’s publication, health-care professionals are encouraged to avoid using medical jargon and phrases (such as “echo,” “stress test,” and “ECG”), because these terms may confuse patients. Instead, health care providers should explain in plain terms the action steps they want a patient to take.43 In 2011, the Heart Failure Society of America described a five-step process for clinicians working with patients who have heart failure,44 culminating in encouraging patients’ use of the “Ask Me 3” questions:45

Physical therapists can use the communication strategies outlined in Box 28-9 to create an effective educational experience to fit the individual learner’s needs. These guidelines can be tailored to a variety of patient populations with differing levels of health literacy.

Patient Adherence

The effectiveness of physical therapy treatment, or of any medical treatment, depends on the patient following the health-care provider’s recommendations (adherence). Unfortunately, there is often a gap between what the patient is asked to do and what the patient actually does. This gap, or nonadherence, has an incidence rate estimated to be between 18% and 35%.46,47 Factors affecting patient adherence include knowledge about the illness and its expected course, complexity of the recommendations, convenience, availability of support system, financial resources, the patient’s beliefs, and the effectiveness of patient education, especially for pulmonary patients.48

Patient education can improve adherence when the information explains what behaviors are expected, when they should be performed, and what to do if problems arise. Plans for patient education sessions should strive to avoid or remove barriers to patient adherence. These efforts include simplifying and individualizing treatment regimens, fostering collaborative teacher-learner relationships, enlisting family support, making use of interdisciplinary and community resources, and providing continuity of care.49 By using an approach that integrates these efforts, the physical therapist can optimize patient adherence to the prescribed physical therapy program.

Interprofessional Considerations and Resources

Health-related organizations can also be rich resources for patient education information. The American Heart Association and the American Lung Association, for example, offermany cardiovascular and pulmonary materials to health-care providers for little or no cost. State public health and local community service agencies may also be sources for printed or audiovisual materials. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has numerous divisions and institutes that address health education and research. Cardiovascular and pulmonary publications can be obtained from the Federal Consumer Information Center, Washington, DC (or at www.hhs.gov).

Community organizations such as YMCA, YWCA, and the American Red Cross offer a wealth of health education materials and classes. Many of these agencies also have catalogs of their educational offerings, which can be obtained by calling their local offices. Local public, medical, and hospital libraries are also useful for seeking out available health education materials. Many Chambers of Commerce keep lists of local support groups or clubs, such as Breather’s Club or Heartbeats. Regional state colleges or universities have departments dedicated to health education and may have cardiovascular and pulmonary materials to share. Please refer to Box 28-10 for a list of trusted online sources of patient information.