Chapter 4 Patient care

Prescriptive guidance with regards to patient care is not appropriate. There is no magic formula when caring for patients and skill must be developed in assessing and adapting to the needs of patients on an individual basis.

Prescriptive guidance with regards to patient care is not appropriate. There is no magic formula when caring for patients and skill must be developed in assessing and adapting to the needs of patients on an individual basis. In addition to caring for the patient, it is important to consider the needs of those accompanying the patient, such as friends, relatives or carers.

In addition to caring for the patient, it is important to consider the needs of those accompanying the patient, such as friends, relatives or carers.ASSESSING THE PATIENT

It is difficult to care for a patient appropriately without first assessing their needs, and anticipating these as early as possible ensures a more pleasant patient experience. When assessing a patient’s needs, the following questions may be helpful:

PAEDIATRICS

GENERAL ISSUES

Preparation

Prior to the child attending for examination:

Is it our turn next Mummy?

It is inevitable that children will sometimes have to wait before an examination; however a child- friendly environment is likely to encourage a child to feel at ease.2

Dealing with parents and guardians

Lastly, it may seem obvious but never leave a baby or toddler unattended, not even for a second. Even if a baby does not appear to be on the move, it only takes a moment for a him to roll over when your back is turned and this could result in serious injury, especially if he falls from a height.

AGE-SPECIFIC ISSUES

The neonate

Babies up to the age of one month are termed neonates (Fig. 4.2). These babies are most commonly encountered on the Special Care Baby Unit (SCBU), although remember that not all neonates requiring imaging are admitted to hospital.

Consider that parents of the neonate:

When dealing with the neonate on SCBU:

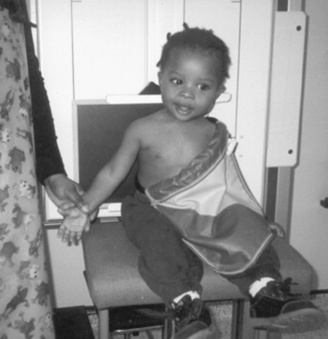

The older baby or toddler

Although young babies tend not to mind who picks them up, as they become more aware of the world around them they begin to become upset if separated from their parent (Fig. 4.3). It is important, therefore, to ensure a familiar person remains with them throughout their examination.

Although restraint should be considered a last resort, it is vital to remember that babies are unlikely to keep still unless they are sleeping. Holding of the baby by the parent or guardian is preferable to the use of restraining devices such as Bucky bands. In such a scenario, radiation safety is essential and the appropriate guidelines for holding patients should be followed. Older toddlers understand a significant amount and so techniques other than physical restraint may prove effective.

The preschool child

Once a child has reached preschool age (3 years and above; Fig. 4.4), his ability to communicate and understand has developed sufficiently to now be aware of his surroundings. Often at this age the hospital environment can seem very frightening and the child is still likely to need his parent present. The need for restraining a child becomes less necessary and time should be spent adequately preparing the child and gaining his trust and cooperation.

The primary school child

Whilst it should become easier to gain cooperation, a child at this age will also be more aware of what is happening to him and distraction may not be as easy (Fig. 4.5). It is important not to treat the child like a baby, as if he is incapable of understanding, but neither is it acceptable to treat him as a little adult. Finding this balance can often be challenging, especially as different children develop at a different pace. Older children often like to feel independent and offering choices can help them to feel less vulnerable. Do bear in mind, however, that offering too many choices can also be overwhelming.

The older child and young adult

As children get older and head towards adulthood they naturally become more independent and may wish to make their own choices with regards to their care. There is no set age at which a patient can take responsibility for their own treatment or care and if a child below the age of 16 is deemed as having sufficient understanding and intelligence, then they may be allowed to determine themselves whether or not they undergo hospital procedures. This is termed ‘Gillick competence’.5 Whilst parents of older children may still wish to accompany their child for an examination, discretion may be needed at times. For example, asking a teenage girl about pregnancy.

NON-ACCIDENTAL INJURY

Non-accidental injury (NAI) can be ‘physical or mental injury, sexual abuse, negligence or maltreatment of a child’.1 Where this is suspected, the child is likely to undergo a skeletal survey. Whilst skeletal surveys for NAI should be performed by two experienced radiographers, if asked to assist or care for the patient it is important to consider the following:

THE ELDERLY PATIENT

With a continuing rise in the elderly population6 it is inevitable that the number of elderly patients you will encounter is also on the increase. Just because a patient is elderly does not mean that they should be treated any differently. Older patients may feel vulnerable and worry about illness not just because of how it affects them personally but also how it may affect those that they care for, such as partners or pets. Many elderly patients have few visitors and may wish to talkat length to relieve their loneliness. In a busy department it can be difficult to devote this extra time; however, these patients may benefit significantly if they feel you have the time to listen.

MOBILITY

Prior to the examination the following should be considered:

Where the patient has a walking aid such as a frame or stick:

Where the patient is a wheelchair user:

VISUAL IMPAIRMENT

HEARING IMPAIRMENT

DEMENTIA AND ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

It must be remembered that not all older people have memory problems or are senile, and we should not treat elderly patients as such; however, as people age, many undergo mental changes. Knowing how to deal with these patients effectively is essential. Dementia is a ‘progressive deterioration in intellectual functioning’,7 affecting thinking, remembering and reasoning. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and, in its early stages, forgetfulness and personality change are common features. As the disease progresses, it affects daily life more and more, reaching the stage where verbal communication is limited and the patient fails to recognise family members. It can be very distressing for friends and relatives to see someone they care about change in this way and they often need as much consideration and reassurance as the patient himself. When dealing with the patient with dementia:

OTHER ISSUES RELATING TO THE ELDERLY

Falls

Falls are a major cause of disability and can lead to mortality in the elderly population.8

Continence

MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS

At any one time, one in six adults suffers from a form of mental illness ranging from depression to schizophrenia.9 Many patients will not require any special care, whilst others may prove challenging. Although the range of mental health problems is vast, here we consider three commonly encountered disorders. Note that dementia is discussed earlier in the chapter.

DELIRIUM/CONFUSION

This has many causes including medication, infection and head injury. Delirium has a sudden onset and is usually short lived, causing confusion, fluctuating awareness, short-term memory loss and disorientation.7 When caring for these patients:

LEARNING DISABILITIES

A person with a learning disability has impaired intellectual and social functioning, and often has difficulty understanding, communicating andremembering new things.8 These difficulties are present at birth or in early childhood but often continue into adult life. Patients with learning disabilities are not all the same and each patient will have different needs. Despite this, there are several general considerations when caring for these patients:

THE TRAUMA OR EMERGENCY PATIENT

EMOTIONAL ISSUES

DEALING WITH AGGRESSION

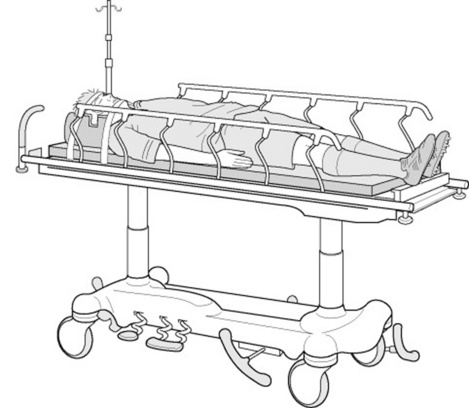

PATIENTS ON A TRAUMA TROLLEY

Patients will be encountered who are immobilised on a trolley (Fig. 4.6), often due to suspected spinal injury. When dealing with these patients:

PAIN

FRIENDS AND RELATIVES

When dealing with friends and relatives of the trauma or emergency patient:

THE UNCONSCIOUS PATIENT

There are several considerations when caring for the unconscious patient:

1 Hardwick J, Gill C. Radiography of children: a guide to good practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2004.

2 Drummond M, York C. Evaluating paediatric practice and care. Synergy. 2001;Feb:20-21.

3 Kurfis Stephens B, Barkey M, Hall H. Techniques to comfort children during stressful procedures. Accid Emerg Nurs. 1999;7:226-236.

4 Martin A. Salthouse. Imaging children: do’s and don’ts. Synergy. 1999;Aug:11-13.

5 Dimond B. Legal aspects of radiography and radiology. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002.

6 Coni N, Nicholl C, Webster S, Wilson K. Lecture notes on geriatric medicine. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003.

7 Bauer B, Hill S. Mental health nursing: an introductory text. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000;101.

8 Department of Health. Valuing people: a new strategy for learning disability for the 21st century. London: HMSO, 2001.

9 Department of Health. National service framework for mental health. London: HMSO, 1999.

10 Walsh M, Kent A. Accident and emergency nursing, 4th edn. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2001.

11 Rideout A. The unconscious patient. Toulson S, editor. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2001:142-171.

Culmer P. Chesneys’ care of the patient in diagnostic radiography. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995.

Gunn C, Jackson C. Guidelines on patient care in radiography, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1991.

Hardwick J, Gill C. Radiography of children: a guide to good practice. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2004.