Chapter 1 Patient Assessment

A cosmetic surgery patient requires a different evaluation from the patient who is seeking a reconstructive procedure. Since the former is an elective surgery, decisions regarding the patient’s medical suitability to undergo surgery, patient preparation and selection of a procedure that will successfully fulfill the aesthetic objectives must be approached with more scrutiny every step of the way.

Summary

Introduction

Careful listening to the patients’ statements, exploration of their reasons for surgery and their expectations from the surgery, may lead the surgeon to suspect that a patient may have, at least, unrealistic expectations from the surgery or even perhaps body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Visits to numerous plastic surgeons’ offices, having undergone multiple surgeries with resultant dissatisfaction and/or disparaging remarks about the previous surgeon should alert the examining surgeon to the need for exercising more caution, analyzing the patient’s emotional stability more in depth and, if deemed necessary, seeking consultation from a psychiatrist or a psychologist, especially when a depressive or dysmorphic type disorder is suspected. A morose, tearful patient who sees only the negative aspect likely suffers from a depression, while the patient with BDD either sees a deformity that does not exist or sees a great deal more than is present (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Alarming clues suggestive of further patient assessment or avoidance of surgery

| You have an uncomfortable feeling about the patient |

| Patient exhibits clinical signs of emotional instability |

| Patient’s expectations seem unrealistic |

| Patient’s objectives are in conflict with your aesthetic judgment |

| Patient provides you with deceitful information |

| Patient demands guarantees |

| Patient makes disparaging remarks about the previous surgeon |

| Patient asks you to take part in keeping the truth about surgery from the spouse |

| Patient treats you or your staff disrespectfully |

| Patient appears to have difficulty comprehending the recommended course |

The mean age of BDD onset is 16.4 ± 7 years, although most patients don’t seek treatment until their late thirties.1,2 The course of the disorder tends to be continuous rather than episodic and complete remission of symptoms appears to be rare, even after treatment. The disorder appears to affect men and women with equal frequency.2,3 Male patients may be more likely to be unmarried.

Clinical features of BDD include varying degrees of preoccupation with perceived defects. Men may become preoccupied with their genitals, height, hair and body build, whereas women typically report concerns with their weight, hips, legs and breasts. Some patients may present with highly specific concerns (e.g. perceived asymmetry of a body part), whereas others may have vague complaints (e.g. concern that a body part just does not look right). Rhinoplasty, liposuction and breast augmentation are among the most frequently sought surgical procedures by the patients afflicted with BDD.4,5 Seven to fifteen percent of cosmetic surgery patients meet criteria for BDD.

Medical History

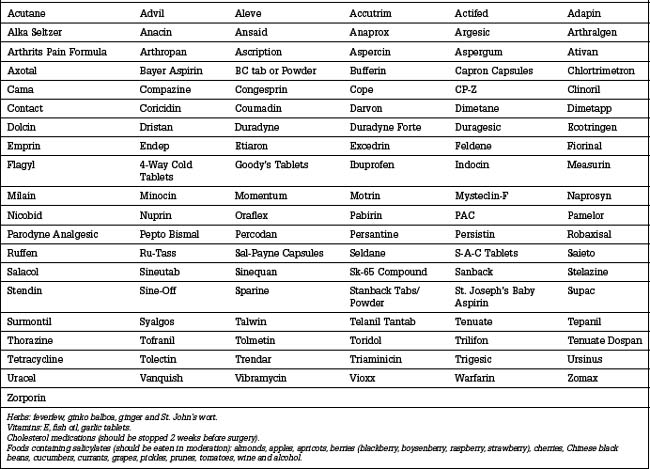

Consumption of prescription, over-the-counter or herbal medications should be investigated carefully (Table 1.2). These may have deleterious effects on surgery and recovery by causing intraoperative bleeding, subsequent hematomas and delayed healing.

Patients in the age group of 50 years or older, and those with known medical conditions that could potentially increase the risk of surgery, should undergo a full medical check up, or an ophthalmology examination within 1 year of surgery if eyelid surgery is being considered.

The most common medical condition that may have deleterious influence on an aesthetic surgery outcome is hypertension. Undoubtedly, controlling the hypertension plays a prodigious role in reducing the risk of postoperative hematoma development. The patient’s blood pressure must be normalized during the several weeks before surgery. If the patient is consuming medications that may contract the blood volume, the surgeon must exercise caution for any developing intraoperative hypotension and, if it occurs, it should be corrected before the incisions are closed. Otherwise, hypotension prevents visualization of the transected blood vessels since they do not bleed, which can start bleeding when the blood pressure rises to the normal level post operatively. In other words, it is the relative hypertension that may cause postoperative hematomas.6

Diabetes is another condition that may lead to postoperative complications.7 Patients with a positive family history of diabetes may have a weakened immune system without clinical or laboratory evidence of diabetes, causing infectious complications that would not otherwise occur under ordinary circumstances. A history of recurrent infection or poor healing on a patient with a family history of this condition, may aid in diagnosing previously undetected diabetes.7 When diabetes is suspected and the fasting blood glucose levels are normal, a simple glucose tolerance test can help uncover an unrecognized diabetes. History of easy bruising or prolonged bleeding, if no pharmaceutical products which can cause bleeding have been consumed, should raise the suspicion of some type of coagulopathy, such as Von Willebrand’s disease.7a

Facial Analysis

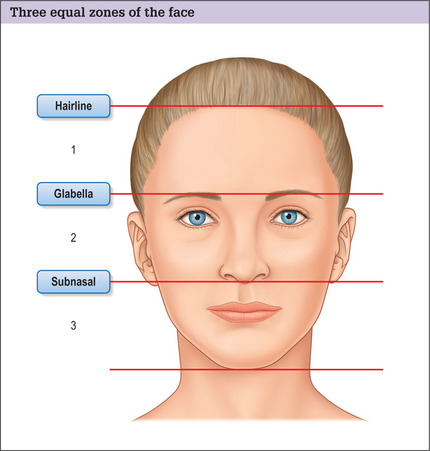

In this chapter we will focus on facial analysis in detail. Analysis of the other parts will be incorporated within the related chapters. To analyze the face in an organized manner, the face is arbitrarily divided into three anatomic zones by three imaginary horizontal lines. The upper line lies at the hairline; the second is at eyebrow level; and the lower line passes through the columella-labial junction (Fig. 1.1). In a comely face these three horizontal lines divide the face into three equal sections. The components of these three zones are appraised individually from frontal and profile views, and likewise the relationships between these units are examined.

Front view of the upper zone

The harmony of the upper aesthetic unit can be marred by a highpositioned hairline, leading to an elongated forehead. This finding is of particular significance when planning the incision for forehead rejuvenation on a patient with a senescent forehead (Fig. 1.2). When the forehead is long, the surgeon may forego a coronal incision or an endoscopic forehead rejuvenation and choose a pretracehial incision, using either the subcutaneous or subgaleal dissection to reduce the forehead height.8,9

Deep wrinkles in the forehead area are commonly the result of compensation of the frontalis muscle to minimize the effects of eyebrow or eyelid ptosis (Fig. 1.3). Thus, it is critical for the surgeon to relax the forehead before selecting a forehead rejuvenation procedure. This can often be accomplished by asking the patient to smile. Usually a compensatory elevation of the eyebrow is eliminated while smiling. The second approach is to ask the patient to close the eyes tightly, and then gently start opening the eyes until the patient can see the viewer. The compensation will become evident as soon as the patient is asked to open the eyes at libre. Analyzing the type of existing wrinkles also aids in choosing a more effective forehead rhytidectomy procedure. In general, deep forehead wrinkles do not respond as favorably to a subgaleal forehead rhytidectomy or an endoscopic forehead rejuvenation. A subcutaneous approach may produce a more successful result in patients with pronounced forehead wrinkling.10 A combination of endoscopic forehead rejuvenation and laser resurfacing is a logical choice for those who exhibit eyebrow ptosis and many fine wrinkles.

Profile view of the upper zone

Reviewing the lateral portion of the forehead helps the surgeon to determine the position of the temple hair in relation to the lateral canthus. If the hairline is receding at the temple area and the patient is considering a facial rhytidectomy (Fig. 1.4), one may choose the anterior hairline temple incision11,12 over the incision placed within the hair-bearing temple.

The forehead profile contour should be smooth and pleasing. Any imperfections, such as frontal protrusion and recession, can be the result of a variety of pathologic conditions. Most commonly, the forehead contour abnormality results from bony protrusion caused by sinus hyperaeration (frontal bossing) (Fig. 1.5) and, less commonly, it results from soft tissue excess.13 Not only do these flaws reduce the desirability of the forehead contour; they may influence the outcome of other aesthetic procedures, such as rhinoplasty. A small ridge cranial to the eyebrow is an acceptable masculine characteristic. Presence of a ridge on a woman, or an exaggerated prominence on either gender, may require aesthetic contouring of the frontal bone. Additionally, as a consequence of aging, the round and slightly projected glabellar area may appear flat or even depressed to varying degrees. Correction of this flattening undoubtedly bestows a rejuvenated appearance to the forehead.

Front view of the middle zone

Most imbalances involve the middle and lower areas of the face. The upper border of the eyebrows should be located at least 2.5 cm above the mid pupil level on a straight gaze.14 The medial end of a pleasing eyebrow is caudal to the lateral extreme, and the highest portion of the eyebrow arch is at the junction of the lateral third with the medial two-thirds of the eyebrow, corresponding to the lateral limits of the limbus in a straight gaze. Eyebrow ptosis results in crowding of the orbital region and must be differentiated from blepharodermachalasia. Any asymmetry in the level or the shape of the eyebrow arch may require differential eyebrow ptosis correction.

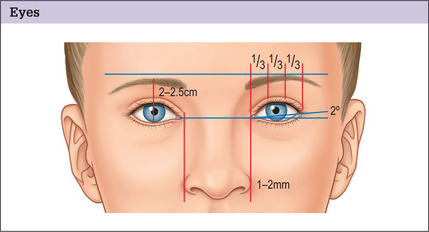

The distance between the medial canthi (intercanthal distance) that is normally approximately 31-33 mm, equals the distance between the medial and lateral canthi (orbital fissure width) (Fig. 1.6). This relationship becomes particularly important when dealing with rhinoplasty candidates who would benefit from refinement of the nasal dorsum and adjustment of the alar bases. Adding to the radix creates an illusion of reduced intercanthal distance, which is detrimental to those patients who exhibit hypotelorism, whereas reduction of the nasal dorsal projection produces the opposite effect.15 Even slight hypotelorism is undesirable and detracts significantly from the patient’s attractiveness. Narrowing the distance of the nasal bones spawns an illusion of decreased intercanthal distance.8

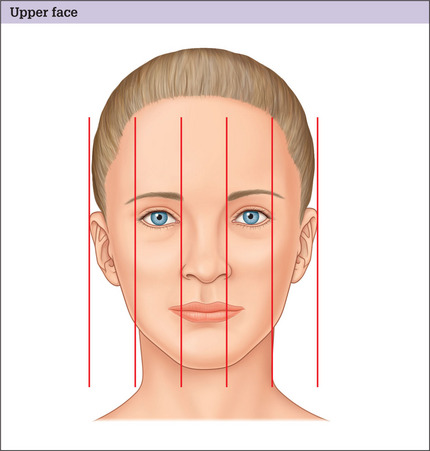

The upper portion of the midface can be divided into five equal segments, two are occupied by the eyes; one extends from one medial canthus to another, containing the root of the nose; and two extend from the lateral canthi to the lateral boundary of the ipsilateral temple area (Fig. 1.6). Disharmony of this area has a significantly ruinous effect on the pulchritude of the face. Anteroposterior discrepancies of the eyes cannot be fully noticed on a frontal view, but are more perceptible on a basilar view. Detection of level and depth abnormalities of the eye is important so that the patient can be informed of structural abnormalities that may fail usual efforts at achieving balance in this part of the face.

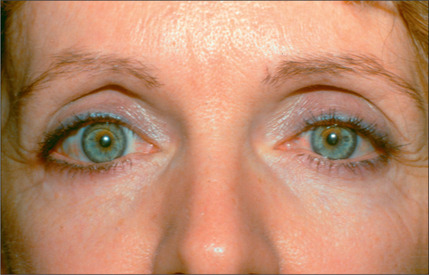

Edema around the eyes in a blepharoplasty candidate may indicate abnormal thyroid dysfunction or renal failure (Fig. 1.7). Bilateral or unilateral exophthalmus may be the consequence of hyperthyroidism (Fig. 1.8). On patients who are contemplating blepharoplasty, vision and lacrimal function also should be assessed. A combination of slight proptosis and dry eyes or borderline tear production is inauspicious and can lead to a troublesome postoperative course.

Fig. 1.8 Patient seeking blepharoplasty to correct exophthalmus was discovered to have hyperthyroidism.

The optimal vertical opening of one eye is approximately 10 mm, placing the upper eyelid margin 1 mm below the upper limits of the limbus. In the aesthetic surgery patient population, mild-to-moderate upper eyelid ptosis is common, but can easily be missed. This condition is readily corrected using one of several available techniques. In a harmonious face the lateral canthus is generally 2° higher than the medial canthus, giving a slight slant to the eye fissure. The antipode of this relationship gives the patient a tired and sad appearance (Fig. 1.9), typically seen in patients with craniofacial deformities, such as Treacher-Collins syndrome, and in patients with lateral lid lag following lower blepharoplasty (Fig. 1.10).

Fig. 1.10 Patient with iatrogenic displacement of lateral portion of lower eyelid and lateral canthus.

As stated, unilateral or bilateral proptosis is an important finding that may present as only a slight asymmetry and excessive opening of one eye or both eyes, or as a significant prominence of the globes. Often this finding is an indication of a thyroid dysfunction and, therefore, it necessitates a careful medical evaluation before blepharoplasty. Generalized thickening of the upper and lower eyelids may be a reflection of hypothyroidism, which should be investigated thoroughly before any periorbital surgical endeavor. Occasionally the lacrimal glands are ptotic and present as an excessive bulk along the lateral portions of the upper eyelids. In this case, lacrimal gland suspension should be discussed with the patient. Neither this condition nor suspension of the gland is of functional significance.16

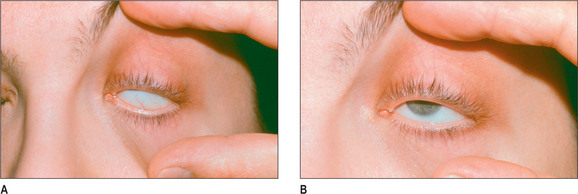

Ideally, the supratarsal fold is visible about 3-4 mm above the lid margin on a straight gaze while this distance is about 10-11 mm when the eyelids are closed. A levator dehiscence is suspected when the tarsal show is increased in the cephalocaudal dimension with a more pronounced supratarsal crease. If eyelid ptosis is diagnosed, levator function must be checked because it is a crucial factor in the selection of a corrective approach. Presence of Bell’s phenomenon indicates a reduced risk of exposure keratitis if complications, such as lid lag, occur. To conduct the test for Bell’s phenomenon, the examiner asks the patient to force the eyes closed while the examiner attempts to open the eyelid by lifting the lid with a finger. With a positive Bell’s phenomenon, the globe rolls cephalad, protecting the cornea under the upper lid (Fig. 1.11). A negative Bell’s phenomenon may be indicative of a potential for an increase in corneal exposure; hence, dryness and ulceration of the cornea should a lid lag ensue post eyelid surgery.

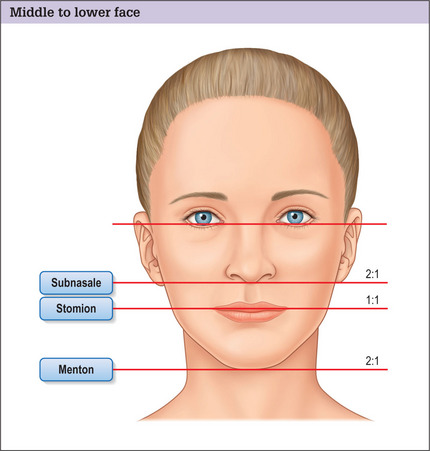

Any depression in the nasojugal area or cephalad to the infraorbital rim may necessitate soft tissue repositioning or fat grafting. Malar bone hypoplasia, although better judged in the profile view, may be detected in the frontal view as well. When evaluating the nose, the examiner must observe the width, direction and smoothness of the dorsal contour. The cephalocaudal nose length, defined as the distance from the nasion to the caudal border of the infra tip lobule, is twice the distance from the columella-labial junction (subnasale) to the junction of the lips (stomion) and equals the distance from the stomion to the menton (base of the chin) (Fig. 1.12). The nasal dorsum and the tip should be in line with the midline of the other facial structures. Any abnormalities can be easily ascertained by drawing an imaginary vertical line starting from the glabella. The nose tip, the philtum dimple and the center of the chin should all fall on the same line.

The quality of the nasal skin is a significant factor in planning surgery and achieving the intended objectives.10 Patients who have thicker skin usually are not optimal candidates for rhinoplasty because the tip would not be as well-defined post operatively. On the other hand, patients who have very thin skin tend to reveal every imperfection in the nasal frame. Both extreme cases require a change in the surgical planning, and the incidence of revisional surgery could be higher on these patients because of these adverse conditions. A thorough explanation of the reasons for potential revisional surgery may result in lesser postoperative dissatisfaction in these patients.

The nasal bones should line up symmetrically, allowing a graceful transition of shadow from the eyebrows to the nasal tip through a pair of smooth and pleasing dorsal lines. Any excess or deficiency of nasal bone width, unilateral or bilateral may distort these lines.17

The distance between the alar bases, as measured from the lateral border of one alar base to its opposite counterparts, should be slightly wider than the intercanthal distance. An imaginary line drawn vertically from the medial canthi should pass 1-2 mm on the inside of the alar base, providing that the intercanthal distance is normal (Fig. 1.13). If the intercanthal distance is abnormal, the alar base distance should be 2 mm wider than the orbital fissure width (from the medial to the lateral canthus).18 The pleasing nasal tip has two highlights. The distance between these two points matches the width of optimal nasal dorsal lines.

Profile view of the middle zone

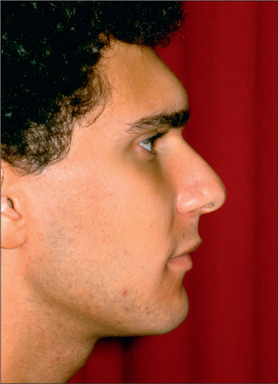

On the profile view, the supraorbital rims are about 10-15 mm anterior to the globes. The nasion, the most depressed portion of the nasal dorsum, is located at the level of the upper lid margin on a straight gaze and is 4-6 mm deep in relation to the glabella. The nasal dorsum creates a 34° angle with the vertical facial plane on a woman and a 36° angle on a man. In both men and women there is a gentle and gradual curve of the dorsum extending from the nasion to the tip; the deepest portion is 0.5-1 mm for a man and 1-1.5 mm for a woman. The nasolabial angle measures 105-108° for a woman and 95-100° for a man.19 A desirable tip definition includes a small supratip break on the profile view. The inferior border of the columella is approximately 4 mm caudal to the alar rim on the lateral view and the alar base is about 2 mm cephelad to the subnasale.20

The malar soft tissue is projected anterior to the most prominent portion of the optical globe. Reversal of this relationship produces a negative lower lid vector, potentiating the chance of lid retraction and postoperative dry eye syndrome.21

Front view of the lower zone

The upper lip is slightly thinner than the lower lip. The width of the oral commissure equals the distance from one medial limbus to the other side. On frontal view the lower jaw line is well defined in a symmetric fashion, with the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) being tight and smooth. Ptosis of the SMAS and fat is an integral part of gravity effects and the aging process, which causes jowls to develop and the lower face to widen. A horizontal line connecting the oral commissures runs parallel to the lines connecting the canthi. The oral commissures are located horizontally on young patients, whereas senescent patients demonstrate claudal tilt of the oral commissures. The philtrum dimple is bordered with a well-defined cupid’s bow. Excess submental fat may obscure the chin definition and hide enlarged or ptotic submaxillary glands and they can only be detected by palpation.

Profile view of the lower zone

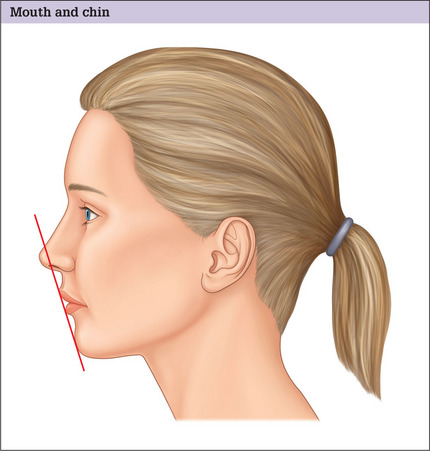

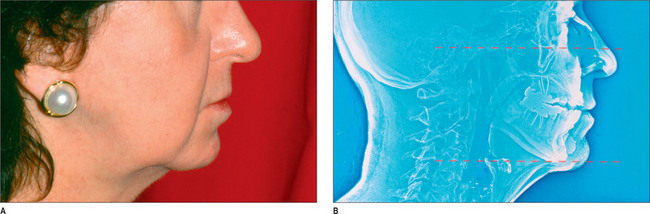

The labiomental groove is often well defined and approximately 4 mm deep. This is one of the most underestimated features of the face. An imaginary line touching the most projected portions of the upper and lower lips should touch the most anterior portion of the chin (Reidel’s plane) (Fig. 1.14).22 A deficient or excessive chin may be easily detected by this simple examination. Patients with receding chins who already exhibit a deep labiomental groove often have retrognathia and usually are not good candidates for genioplasty alone. Commonly, mandibular advancement, with or without a genioplasty, serves these patients best.

The cervical region

Ellenbogen has described the attributes of an aesthetically pleasing neck whereby a 100 angle is created between the chin and the neck.23 This angle can be altered by a variety of neck flaws. These could include: excess skin, presence of platysmal muscle bands, excess subplatysmal and supraplatysmal fat, a malpositioned hyoid bone (Fig. 1.15),24 a receding chin, or a varying combination thereof. A ptotic or enlarged submaxillary gland may also disturb the balance of the cervicomental region.

The basilar view

Evaluation of the face on basilar view is crucial to a thorough facial assessment. In this view, any asymmetry of the forehead can be detected easily. More importantly, the anteroposterior eye globe position can be observed more precisely. The malar bones, their symmetry and the overlying soft tissue prominence also can be evaluated clearly in this view. The columella direction and nostril asymmetry also are more detectable in this view. Additionally, the chin position and its line-up with respect to the rest of the face are more clearly identified in this position. Also, the ear projection is assessed more readily with the head tilted back.

1. Phillips K.A., Diaz S. Gender differences in body dysmorphic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:570.

2. Phillips K.A., Menard W., Fay C., et al. Demographic characteristics, phenomenology, comorbidity, and family history in 200 individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:317.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

4. Crerand C.E., Franklin M.E., Sarwer D.B. Body dysmorphic disorder and cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:167E-180E.

5. Crerand C.E., Phillips K.A., Menard W., et al. Non-psychiatric medical treatment of body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics. 2006;46: 549.

6. Beckenstein M, Guyuron B. Postrhytidectomy hematomas and “relative” hypertension. 1994. Unpublished data

7. Guyuron B., Rasqewski R. Undetected diabetes and the plastic surgeon. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:471-474.

7a. Guyuron B., Zarandy S., Tirgan A. Von Willebrand’s disease and plastic surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;32:351-355.

8. Connell B. Brow ptosis: local reactions. In Third International Symoseum on Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Eye and Adnexa. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1982.

9. Guyuron B., Davies B. Subcutaneous anterior hairline forehead rhytidectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1988;12:77-83.

10. Guyuron B. Precision rhinoplasty. II. Prediction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81:500-505.

11. Guyuron B. Modified temple incision of facial rhytidectomy. Ann Plast Surg. 1988;21:439-443.

12. Lewis C.M. Preservation of the female sideburn. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1984;8:91.

13. Guyuron B. Soft-tissue frontal bossing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:296-297.

14. McKinney P., Mossie R.D., Zukowski M.L. Criteria for the forehead lift. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1991;15:141-147.

15. Guyuron B. Dynamics of rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;80:970-978.

16. Guyuron B., DeLuca L. Aesthetic and functional outcomes of dacryoadenopexy. Aesthetic Surgery Quarterly. 1996;16:138-141.

17. Sheen J. Aesthetic rhinoplasty, 2nd edn, St Louis: Mosby, 1987. vol. 2

18. Guyuron B. Precision rhinoplasty. I. The role of life-size photographs and soft-tissue cephalometric analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81:489-499.

19. Guyuron B., Davies B. Experience with the modified Putterman procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;82:775-780.

20. Powell N., Humphreys B. Preparation of the aesthetic face. New York: Theime, 1984.

21. Rees T.D., Jelks G.W. Blepharoplasty and the dry eye syndrome. guidelines for surgery? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;68:249-252.

22. Reidel R.A. An analysis of the dentofacial relationships. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1957;43:103.

23. Ellenbogen R., Karlin J.V. Visual criteria for success in restoring the youthful neck. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;80:823-837.

24. Guyuron B., Arons J. The chin, hyoid bone, and neck. World Plast. 1995;3:195-205.