CHAPTER 53 Pathophysiologic Evidence of Injury

Imaging is the conventional approach to finding evidence of injury. When major trauma to the neck results in fractures or dislocations, these are typically evident on plain radiographs of the neck.1 Computed tomography (CT) can provide more detailed reconstructions of the injury. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can reveal soft tissue components or consequences of the injury.

Minor injuries to the neck do not result in major fractures or dislocations. Therefore, such injuries are not evident on imaging.2 Indeed, conventional imaging is typically normal. This lack of evidence of injury on imaging is used by some commentators to infer that there is no injury. That is false. The lack of evidence only reflects the limited resolution on conventional imaging. Plain radiographs or CT demonstrate only lesions in bone; they do not show soft tissue injuries. MRI demonstrates soft tissues, but it will not necessarily reveal small lesions. Normal imaging, therefore, does not exclude the presence of lesions that are beyond the resolution of the imaging technique used.

POSTMORTEM STUDIES

Independent studies, in countries as respectively remote as Sweden3 and Australia,4–6 have provided similar conclusions, which have now been systematically reviewed.7 Both sets of studies harvested the cervical spines of victims of fatal motor vehicle accidents. The Australian studies included victims who survived for various periods after the accident. The pathology of major head injury and suboccipital injuries was ignored. Instead, the studies focused on other lesions, which were not the cause of death, but which indicated what could happen to the cervical spine, in a motor vehicle accident.

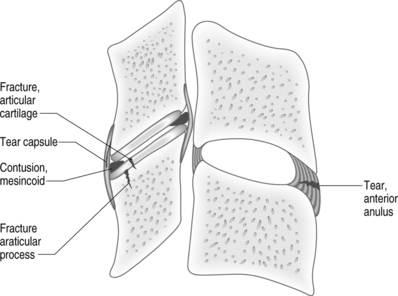

The same spectrum of injuries was consistently observed (Fig. 53.1). They included tears of the anterior anulus fibrosus, avulsion of the anterior anulus, contusions of the posterior anulus, tears or avulsions of the capsules of the zygapophyseal joints, contusions of the meniscoids of these joints, intra-articular hemorrhage, fractures of the articular cartilage, and subchondral or greater fractures of the articular pillars. Conspicuously, virtually none of these lesions was evident on plain radiographs of the cervical spine, taken postmortem, even when read retrospectively with the knowledge that a lesion was present.3–6

These lesions are consistent with the known biomechanics of whiplash injury.2 Anterior separation of the vertebral bodies could cause tears or avulsions of the anterior anulus fibrosus. Posterior impaction of the zygapophyseal joints could cause articular and subarticular fractures, or contusions of the intra-articular meniscoids. Excessive separation of the zygapophyseal joints, in extension or in flexion,8 could cause tears of the joint capsules.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

For these lesions to be symptomatic the structures in which they occur have to be innervated. In the cervical spine, the anuli fibrosi of the intervertebral discs are innervated, and the zygapophyseal joints are innervated. The discs receive their innervation from the vertebral nerve, the sympathetic trunks, and the sinuvertebral nerves.9 The zygapophyseal joints are innervated by the medial branches of the cervical dorsal rami.10

CLINICAL STUDIES

Discography

Cervical discography is a procedure designed to determine if a particular intervertebral disc is painful or not.11 It involves introducing into the nucleus of the disc a needle, which is used to stress the disc with an injection of contrast medium. The test is deemed to be positive if the patient’s pain is reproduced, but provided also that stressing adjacent discs does not reproduce the pain. Furthermore, in order to be valid, cervical discography must reproduce the patient’s pain to a clinically significant extent. The operational criteria require an intensity of evoked pain of 7 or more on a 10-point scale.12

Cervical discography has been described extensively in the surgical literature as a means of determining at which segments arthrodesis should be carried out for the treatment of neck pain.13–16 Other information, however, is scarce. No studies have shown what the prevalence is of discogenic neck pain, as diagnosed by discography. No studies have shown that cervical fusion for neck pain is particularly successful. None has shown that discography leads to better outcomes. Meanwhile, two studies have warned of the capricious validity of cervical discography.

It is uncommon for a single cervical disc to be painful alone. More often, two, three, or more discs appear symptomatic.17 Indeed, the more segments that are investigated, the more discs emerge as painful. Consequently, cervical discography is not complete unless every cervical disc is studied.

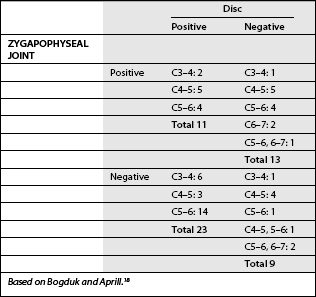

Cervical discography can be false-positive. The movement that discography induces can stress the zygapophyseal joints of the same segment. If these, rather than the disc, are the source of pain, the discography appears to reproduce the patient’s pain, but falsely so.18 The disc is not the source of pain; the zygapophyseal joints are. For this reason, some 25% of positive discograms are false-positive (Table 53.1).

Medial branch blocks

In contrast to cervical discography, the science of cervical medial branch blocks is highly developed, and has been extensively tested for validity and utility. These blocks test if a particular zygapophyseal joint is painful or not. They are based on the principle that if the joint is painful then anesthetizing the medial branches that innervate it should relieve that pain (Fig. 53.2).

The face validity of cervical medial branch blocks has been established.19 When small volumes of local anesthetic are used (0.3 mL) to anesthetize a given nerve, the injectate does not spread to adjacent structures that might be alternative sources of pain. It does not spread to adjacent medial branches; it does not spread to the spinal nerve; it does not indiscriminately anesthetize the posterior neck muscles. The injectate pools around the target nerve, and spreads only in a planar fashion along the cleavage plane between multifidus and semispinalis capitis.

The construct validity of cervical medial branch blocks has been established in several ways. Single diagnostic blocks are not valid. They can be associated with a false-positive rate of up to 27%.20 To be valid, blocks must be controlled in each and every case that they are used. These controls can be placebo controls or comparative blocks. Comparative blocks have been validated using statistical methods,21 and by comparing them with placebo-controlled blocks.22 Furthermore, their diagnostic validity has been confirmed by successful subsequent treatment. Denervating the painful joint by radiofrequency neurotomy provides complete and lasting relief of the pain.23–25

Implications

Among patients with neck pain after whiplash, two separate studies from the same unit have established the prevalence of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain to be 54%26 and 60%.27 A third study from the same unit established the prevalence of zygapophyseal joint pain in drivers injured in high-speed motor vehicle accidents to be 75%.28 An unrelated study, from a pain clinic serving a general population, found the prevalence of zygapophyseal joint pain to be at least 36%.29 This figure constituted a worst-case analysis. Patients who did not return for control blocks were not treated as positive. Another study from a pain clinic reported a prevalence of 60%.30

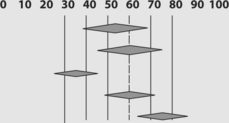

The confidence intervals of these various studies overlap (Table 53.2). Collectively, they paint a consistent picture. Zygapophyseal joint pain accounts for some 60% of patients with chronic neck pain after injury. The pattern of involvement is diverse. Single joints may be painful, or both joints of a particular segment may be painful. Joints at other, adjacent or remote segments may be painful. The more common patterns are one or both joints painful at C5–6, or C2–3; and joints painful at C5–6 and C2–3. Less often, consecutive joints, at C5–6 and C6–7, are painful.

Table 53.2 The prevalence and 95% confidence intervals of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain amongst patients with chronic neck pain

| Study | Prevalence | 95% Confidence Intervals |

|---|---|---|

|

||

| Barnsley26 | 54% | |

| Lord27 | 60% | |

| Speldewinde29 | 36% | |

| Manchikanti30 | 60% | |

| Gibson28 | 75% |

The prevalence and distribution of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain correlate with two other, and independent, lines of evidence. The postmortem data point to injuries of the zygapophyseal joints that should be painful.3–6 The biomechanics data reveal that the mechanism of whiplash could cause injury to the zygapophyseal joints, of the nature found at postmortem.2 Furthermore, the biomechanics data implicate C5–6 and C2–3 as the most likely segments to be involved. Consequently, the postmortem data, the biomechanics data, and the clinical data, all point to the same conclusion. This constitutes convergent validity for the concept that cervical zygapophyseal joints can be injured and do became painful.31

1 Cusick JF, Yoganandan N. Biomechanics of the cervical spine 4: major injuries. Clin Biomech. 2002;17:1-20.

2 Bogduk N, Yoganandan N. Biomechanics of the cervical spine. Part 3: minor injuries. Clin Biomech. 2001;16:267-275.

3 Jónsson HJr, Bring G, Rauschning W, et al. Hidden cervical spine injuries in traffic accident victims with skull fractures. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:251-263.

4 Taylor JR, Twomey LT, Corker M. Bone and soft tissue injuries in post-mortem lumbar spines. Paraplegia. 1990;28:119-129.

5 Taylor JR, Twomey LT. Acute injuries to cervical joints: An autopsy study of neck sprain. Spine. 1993;9:1115-1122.

6 Taylor JR, Taylor MM. Cervical spinal injuries: an autopsy study of 109 blunt injuries. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 1996;4:61-79.

7 Uhrenholt L, Grunnet-Nilsson N, Hartvigsen J. Cervical spine lesions after road traffic accidents. A systematic review. Spine. 2002;27:1934-1941.

8 Pearson AM, Ivancic PC, Ito S, et al. Facet joint kinematics and injury mechanisms during simulated whiplash. Spine. 2004;29:390-397.

9 Bogduk N, Windsor M, Inglis A. The innervation of the cervical intervertebral discs. Spine. 1988;13:2-8.

10 Bogduk N. The clinical anatomy of the cervical dorsal rami. Spine. 1982;7:319-330.

11 Bogduk N, Aprill C, Derby R. Discography. In: White AH, editor. Spine care, volume one: diagnosis and conservative treatment. St Louis: Mosby; 1995:219-238.

12 Schellhas KP, Smith MD, Gundry CR, et al. Cervical discogenic pain: prospective correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic subjects and pain sufferers. Spine. 1996;21:300-312.

13 Cloward RB. Cervical diskography. A contribution to the aetiology and mechanism of neck, shoulder and arm pain. Ann Surg. 1959;130:1052-1064.

14 Kikuchi S, Macnab I, Moreau P. Localisation of the level of symptomatic cervical disc degeneration. J Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63B:272-277.

15 Whitecloud TS, Seago RA. Cervical discogenic syndrome. Results of operative intervention in patients with positive discography. Spine. 1987;12:313-316.

16 Garvey TA, Transfeldt EE, Malcolm JR, et al. Outcome of anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion as perceived by patients treated for dominant axial–mechanical cervical spine pain. Spine. 2002;27:1887-1894.

17 Grubb SA, Kelly CK. Cervical discography: clinical implications from 12 years of experience. Spine. 2000;25:1382-1389.

18 Bogduk N, Aprill C. On the nature of neck pain, discography and cervical zygapophyseal joint blocks. Pain. 1993;54:213-217.

19 Barnsley L, Bogduk N. Medial branch blocks are specific for the diagnosis of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. Reg Anesth. 1993;18:343-350.

20 Barnsley L, Lord S, Wallis B, et al. False-positive rates of cervical zygapophyseal joint blocks. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:124-130.

21 Barnsley L, Lord S, Bogduk N. Comparative local anaesthetic blocks in the diagnosis of cervical zygapophyseal joints pain. Pain. 1993;55:99-106.

22 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Bogduk N. The utility of comparative local anaesthetic blocks versus placebo-controlled blocks for the diagnosis of cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:208-213.

23 Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721-1726.

24 Lord SM, McDonald GJ, Bogduk N. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy of the cervical medial branches: a validated treatment for cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. Neurosurg Quart. 1998;8:288-308.

25 McDonald G, Lord SM, Bogduk N. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with cervical radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:61-68.

26 Barnsley L, Lord SM, Wallis BJ, et al. The prevalence of chronic cervical zygapophyseal joint pain after whiplash. Spine. 1995;20:20-26.

27 Lord S, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, et al. Chronic cervical zygapophyseal joint pain after whiplash: a placebo-controlled prevalence study. Spine. 1996;21:1737-1745.

28 Gibson T, Bogduk N, Macpherson J, et al. Crash characteristics of whiplash associated chronic neck pain. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 2000;8:87-95.

29 Speldewinde GC, Bashford GM, Davidson IR. Diagnostic cervical zygapophyseal joint blocks for chronic cervical pain. Med J Aust. 2001;174:174-176.

30 Manchikanti L, Singh V, Rivera J, et al. Prevalence of cervical facet joint pain in chronic neck pain. Pain Physician. 2002;5:243-249.