1

Pathology of oesophageal and gastric tumours

Oesophagus

Epithelial tumours of the oesophagus and the gastro-oesophageal junction

Malignant tumours

Squamous cell carcinoma: Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumour of the oesophagus worldwide and affects men two to ten times more often than females, with an average age between 50 and 60 years at time of diagnosis. There is a marked geographic and ethnic variation in incidence. Incidence rates are highest in Iran, China, South America and Eastern Africa and are higher in African-Americans than Caucasian-Americans regardless of gender.

The intake of hot beverages has been shown to increase the risk of squamous cell carcinoma. Furthermore, dietary factors such as a lack of fresh fruit and vegetables and high intake of barbecued meat or pickled vegetables most likely play a role in the aetiology of squamous cell carcinoma. Human papilloma virus infection has been implicated in the pathogenesis of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, but its precise role is still controversial at present. Patients with achalasia have an increased risk of developing cancer compared to the normal population.4 The risk of developing oesophageal carcinoma is also increased in patients with coeliac disease,5 Plummer–Vinson syndrome (also called Paterson–Kelly syndrome),6 tylosis (also called focal non-epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma),7,8 previous ingestion of corrosive substances,9 Zenker’s diverticulum10 or after ionising radiation.11 In the Asian population, polymorphisms in ALDH1B1 and ALDH2, both genes encoding aldehyde dehydrogenases, are associated with squamous cell carcinoma.12

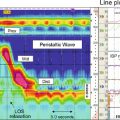

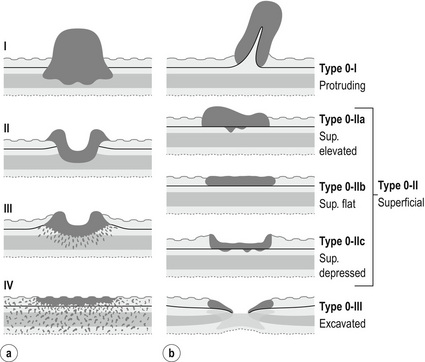

Oesophageal squamous cell carcinomas are found in the upper, middle and lower third of the oesophagus in a ratio of approximately 1:5:2. The macroscopic appearance depends on the depth of tumour invasion and is classified into four different types according to the Japanese classification for oesophageal cancer,13 which is similar to the macroscopic classification of gastric cancer (see Fig. 1.8 below). Approximately 60% of squamous cell carcinomas show an exophytic or fungating growth pattern, 25% are ulcerative and 15% are infiltrative (Fig. 1.1). However, the macroscopic appearance of all cancers can significantly change as a result of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation, with tumour shrinkage, extensive necrosis and fibrosis.

Figure 1.1 Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma located in the middle oesophagus. (a) Fresh oesophagectomy specimen with a polypoid exophytic tumour growth and a smaller flat (red coloured) mucosal abnormality. (b) Lack of (dark) iodine staining in the abnormal areas. (c) Same specimen after fixation. Courtesy of Dr Tomio Arai, Tokyo.

Squamous cell carcinomas invade both horizontally and vertically. In the West, 60% of patients have carcinomas that have invaded beyond the muscularis propria and have regional lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis, whereas in Japan up to 40% of all resected carcinomas are superficial or early carcinomas involving mucosa and submucosa only.14 The frequency of lymph node metastases is related to the depth of tumour invasion and has been reported as less than 5% for intramucosal carcinomas and up to 45% for submucosal carcinomas. Although tumours located in the upper third of the oesophagus are more likely to spread to cervical and upper mediastinal nodes, a significant proportion will also spread to perigastric nodes.

Distant metastases due to haematogenous spread are most commonly found in liver, lung, adrenal gland and kidney.18

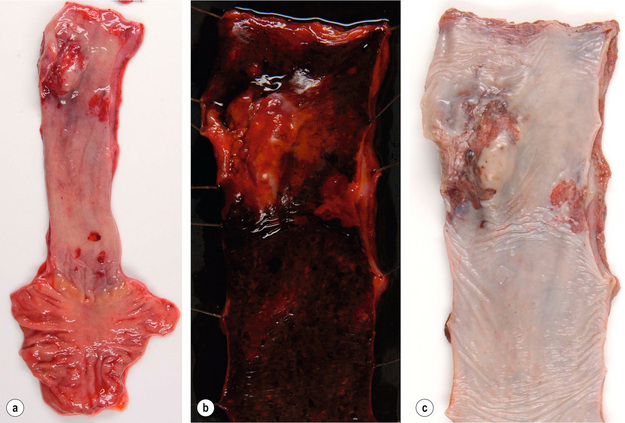

Histologically, squamous cell carcinomas are characterised by keratinocyte-like cells that may or may not have intercellular bridges and show a variable degree of keratinisation (Fig. 1.2). Depending on the extent of mitotic activity, nuclear atypia and degree of squamous differentiation including degree of keratinisation, squamous cell carcinomas are graded as well, moderately or poorly differentiated.12 The histology of squamous cell carcinoma can change dramatically after neoadjuvant chemo(radio)therapy and then typically shows extensive necrosis, inflammation, fibrosis and foreign body-type granulomas around keratin pearls. There is currently no consensus on how to grade tumour regression. The regression grading according to Mandard et al.19 considers the relative proportion of residual viable tumour cells and fibrosis in the primary cancer and is probably currently the one most commonly used in the UK. Very recently, a grading system to assess tumour regression in lymph nodes has been proposed and showed prognostic significance in a small series of patients.20

Figure 1.2 Histological images from specimen in Fig. 1.1. (a) Histology of the nodule shows poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with no evidence of keratin formation and necrosis (pink material) between strands of neoplastic cells. (b) Histology of the flat lesion shows early infiltrative squamous cell carcinoma. Courtesy of Dr Tomio Arai, Tokyo.

Three main variants of squamous cell carcinoma have been described:12

1. Verrucous carcinoma of the oesophagus is a rare, locally aggressive tumour that is more common in males. Macroscopically, the tumour has an exophytic papillary appearance and tumours are usually very large before they become clinically apparent. Microscopically, the tumour is very well differentiated with minimal atypia. Superficial biopsies are often insufficient to distinguish between a squamous papilloma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and verrucous carcinoma.21

2. Spindle cell carcinoma (also known as carcinosarcoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma and polypoid carcinoma) is a polypoid tumour located in the middle or lower third of the oesophagus. Histologically, the tumour is a mixture of a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma and a high-grade spindle cell component that can show osseous, cartilaginous or skeletal muscle differentiation.22 Spindle cell carcinomas are highly aggressive carcinomas, with 5-year survival rates of 10–15%.23

3. Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma is an unusual variant of squamous cell carcinoma that needs to be distinguished from ‘pure’ squamous cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma and neuroendocrine tumours. It is a highly aggressive carcinoma with a very poor prognosis. Histologically, this tumour shows the characteristic basaloid cells together with a mucoid hyaline-like substance, as well as multiple other components.

Precursor lesions of squamous cell carcinoma: Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma development is believed to be a multistep process from normal squamous epithelium via intraepithelial neoplasia (synonym: dysplasia) to invasive carcinoma based on findings in high-risk populations where dysplasia predates the development of carcinoma by approximately 5 years.24,25 In general, dysplasia is defined as the presence of unequivocal neoplastic cells within the epithelium. Squamous cell dysplasia is classified as ‘low grade’ when architectural and cytological abnormalities are seen in the basal half of the squamous epithelium with preserved maturation of the upper half, and as ‘high grade’ when more than the bottom half shows architectural and cytological abnormalities. Full-thickness dysplasia of the squamous epithelium is referred to as ‘carcinoma in situ’ by some authors.

Molecular pathology of squamous cell carcinoma: Up to 80% of squamous cell carcinomas show mutation with consecutive loss or inactivation of the tumour suppressor gene p53 (the ‘guardian’ of the genome located on the short arm of chromosome 17), of the retinoblastoma gene RB and of p16.26 Amplification (e.g. an increase in gene copy number) and subsequent protein overexpression of cyclin D1, a cell cycle regulating gene, occurs in 20–40% of squamous cell carcinomas. Inactivation of FHIT (fragile histidine triad gene, a presumed tumour suppressor gene on chromosome 3p14), DLEC1 (deleted in lung and oesophageal cancer-1) and DEC1 (deleted in oesophageal cancer-1) by genetic or epigenetic mechanisms promoting cancer cell growth has recently been shown. Amplifications of several proto-oncogenes and growth factors such as FGF4 and FGF6 (fibroblast growth factors 4 and 6), EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) and MYC have also been found in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Some of these changes, such as p53 mutations, appear to be an early event as they have also been demonstrated in squamous cell dysplasia. The presence of such genetic changes may be used to select patients for targeted therapy with antibodies or small-molecule inhibitors in the near future.

Adenocarcinoma: Population-based studies in the USA and Europe indicate that the incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma, adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction and proximal stomach has doubled between the 1970s and late 1980s, and continues to increase by 5% every year.2,27 Countries with the highest incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma are the UK, Australia, the Netherlands and the USA. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma is much more common in males (male:female ratio 4:1 to 7:1) and 80% of oesophageal adenocarcinomas occur in the white population.

The relative risk of developing adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus is of the order of 30–60,27 but only 5% of patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma have had a previous diagnosis of Barrett’s oesophagus.28 Other risk factors of oesophageal adenocarcinoma are tobacco smoking, obesity (which may promote gastro-oesophageal reflux), and use of medications that relax the gastro-oesophageal sphincter. No clear association has been found between alcohol consumption or diet and adenocarcinoma. Case–control studies seem to indicate that infection with Helicobacter pylori is protective against oesophageal adenocarcinoma.

There is an ongoing debate whether adenocarcinoma in the proximity of the oesophagogastric junction should be classified as oesophageal or gastric carcinoma. This is mainly related to the fact that there is no consensus on the definition of the ‘gastro-oesophageal junction’ and ten different definitions are listed in the fourth edition of the WHO classification of digestive cancer 2010.12 Siewert and Stein29 defined adenocarcinoma of the gastro-oesophageal junction as ‘tumours that have their centre within 5 cm proximal and distal of the anatomical cardia’ and suggested three tumour types based on the anatomical location of the tumour centre determined by a combination of radiography, endoscopy, computed tomography and intraoperative appearance:

• Type I. Adenocarcinoma of the distal oesophagus, which usually arises from an area with specialised intestinal metaplasia (i.e. Barrett’s oesophagus) and which may infiltrate the gastro-oesophageal junction from above. This entity is also referred to as ‘Barrett carcinoma’. These adenocarcinomas have their centre within 1–5 cm above the cardia.

• Type II. True carcinoma of the cardia arising from the gastric cardia epithelium or from short segments with intestinal metaplasia at the gastro-oesophageal junction. This entity is also referred to as ‘junctional carcinoma’. These adenocarcinomas have their centre within 1 cm above and 2 cm below the cardia.

• Type III. Subcardial gastric carcinoma that infiltrates the oesophagogastric junction and distal oesophagus from below. This entity is also referred to as ‘proximal gastric carcinoma’. These adenocarcinomas have their centre within 2–5 cm below the cardia.

Adenocarcinoma associated with Barrett’s oesophagus: Columnar epithelium in the oesophagus in combination with ulceration and oesophagitis was first described by Norman Barrett in 1950, who was convinced that this was due to a congenitally short oesophagus.30 Moersch et al.31 and Hayward32 were the first to suggest that the columnar lining of the oesophagus might be an acquired condition due to gastro-oesophageal reflux. Experiments conducted by Bremner et al.33 in 1970 in a dog model of gastro-oesophageal reflux strongly supported this concept.

The risk of developing adenocarcinoma appears to be related to the length of the metaplastic mucosa, with 3 cm being used as the cut-off between a ‘short’ and a ‘long’ segment Barrett’s oesophagus. Further details of Barrett’s oesophagus including the proposed metaplasia–dysplasia–adenocarcinoma sequence can be found in Chapter 15.

Barrett’s associated adenocarcinomas are located almost exclusively in the distal third of the oesophagus and often infiltrate into the proximal stomach (Fig. 1.3). Up to 50% of adenocarcinomas show a macroscopic infiltrative growth pattern and only 5–10% are polypoid. Histologically, oesophageal adenocarcinomas are typically papillary and/or tubular (intestinal type according to the Laurén classification35) and are graded as well, moderately or poorly differentiated according to the proportion of tumour that is composed of glands.12 Approximately 10% of all oesophageal adenocarcinomas are of mucinous or signet-ring cell type. Most patients present with locally advanced disease, where the adenocarcinoma has infiltrated beyond the deep muscle layer into the perioesophageal tissue and involves regional lymph nodes in up to 75% of cases. Should the patient present with early disease, it is important to remember that there is a double muscularis mucosae in almost all cases with Barrett’s oesophagus. Carcinomas infiltrating between the two layers of the muscularis mucosae are still to be classified as ‘intramucosal’ pT1a cancers. However, carcinomas that have infiltrated into this double muscularis mucosae layer may be associated with a higher frequency of lymphoangioinvasion and lymph node metastases.36 This has implications for endoscopic treatments.

Figure 1.3 Barrett’s oesophagus with adenocarcinoma is seen on the left. An irregular, partly ulcerated tumour is located at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Between the proximal edge of the tumour and the squamous lined oesophagus is metaplastic columnar epithelium. The squamocolumnar junction (border between the pale appearing squamous epithelium and brownish-appearing metaplastic epithelium) is located at least 2.5 cm proximal to the gastro-oesophageal junction. Courtesy of Dr B. Disep, Newcastle.

Variants of oesophageal adenocarcinoma:

1. Truly non-Barrett’s oesophagus-associated adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus is rare and arises either from heterotopic gastric mucosa (so called ‘gastric inlet’), which can be anywhere in the oesophagus or from the epithelium of submucosal oesophageal glands.

2. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is also very rare. These carcinomas are histologically identical to salivary gland-type adenoid cystic carcinoma and occur more frequently in females.37 These carcinomas arise from submucosal oesophageal glands. They usually form well-circumscribed solid nodules in the submucosa and the overlying squamous epithelium shows no abnormalities. Most tumours show some differentiation towards squamous, glandular or even small cell elements which could indicate an origin from a multipotential stem cell.

Precursor lesions of oesophageal adenocarcinoma and molecular pathology of oesophageal adenocarcinoma are discussed in more detail in Chapter 15.

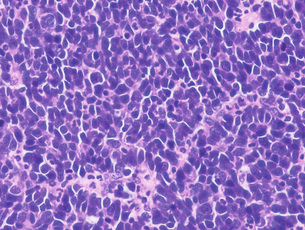

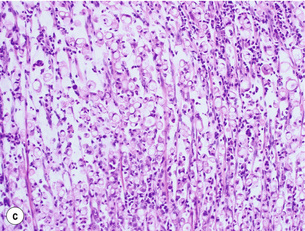

Neuroendocrine tumours of the oesophagus: Oesophageal neuroendocrine tumours are very rare, representing less than 8% of all oesophageal carcinomas. The majority of them are poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (also known as small cell carcinomas) that are highly aggressive and median survival is usually 6–12 months or less. Macroscopically, they appear as exophytic or ulcerative growths measuring on average 6 cm at presentation. Histologically, these may appear as homogeneous tumours (Fig. 1.4) or as a mixture of squamous and mucoepidermoid elements. The histological features including immunohistochemical markers are similar to small cell carcinoma of the lung and the possibility of metastatic or direct spread from the lung should always be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Mesenchymal tumours of the oesophagus:

Leiomyoma: Leiomyoma is the most common benign mesenchymal tumour of the oesophagus, which is twice as frequent in males as females. Leiomyomas are typically located in the distal or middle oesophagus. Most are less than 3 cm in size and form a hard white-greyish mass. In contrast to gastrointestinal stromal tumours, leiomyomas are immunoreactive for desmin and smooth muscle actin and negative for KIT (CD117) and DOG1.

Granular cell tumour: Granular cell tumours are found in the skin, mouth and throughout the gastrointestinal tract, but most frequently in the oesophagus. Nearly two-thirds of these tumours have been found in the lower third of the oesophagus and arise in the submucosa. The covering squamous epithelium is often thickened and may show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The characteristic tumour cells are uniform plump cells with granular cytoplasm that stain with periodic acid–Schiff and S-100 protein.

Stomach

Fundic gland polyps

Fundic gland polyps are the most common type of gastric polyps and were originally described in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome.38 Sporadic fundic gland polyps are found in up to 11% of patients, are more common in middle-aged women and are typically single or few, measuring less than 0.5 cm. The incidence of fundic gland polyps is low in patients with H. pylori infection and high in patients taking proton-pump inhibitors.39 While low-grade dysplasia is frequent in FAP patients with fundic gland polyps, dysplasia is rare in sporadic cases.40

Hyperplastic polyps are composed of epithelial and stromal components, and are most frequently found in the antrum of patients with inflamed or atrophic gastric mucosa. A recent review of more than 8000 gastric polyps showed that only 14% were hyperplastic polyps.39 Hyperplastic gastric polyps are thought to arise as a hyperproliferative response of the gastric foveolae to tissue injury. Removal of the underlying injury such as H. pylori infection resulted in regression of the hyperplastic polyps in 70% of patients.42 1–20% of hyperplastic polyps show foci of dysplasia, p53 mutations, chromosomal aberrations and microsatellite instability, which seem to be related to larger size (> 2 cm).43 Hyperplastic polyps should be regarded as surrogate markers of cancer risk and synchronous or metachronous gastric carcinomas have been reported in up to 6% of cases.

Sporadic intestinal-type adenomas are most common in patients over 50 years of age, three times more frequent in men and most commonly found on the lesser curve of the antrum. They are usually solitary, less than 2 cm in diameter, well circumscribed, pedunculated or sessile, and their prevalence varies widely from 4% in Western countries to 27% in Japan. Adenomatous polyps are precursors of gastric adenocarcinomas and the risk of adenocarcinoma seems to increase with increasing size. Fifty per cent of adenomatous polyps > 2 cm harbour an adenocarcinoma.44

Polyposis syndromes

Hamartomatous polyps in the stomach have been found in patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, juvenile polyposis, Cronkite–Canada syndrome and Cowden disease. With the exception of Peutz–Jeghers polyps, the histological features of these polyps overlap with those of sporadic hyperplastic polyp and the pathological diagnosis of a ‘syndromic polyp’ will require knowledge of the suggestive clinical context. All patients with the above mentioned polyposis syndromes have an increased risk of developing gastric carcinoma that appears to be highest in patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome at 30%.45 Up to 80% of patients with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome have a germ-line mutation of the STK11/LKB1 gene that encodes an enzyme responsible for cell division, differentiation and signal transduction. The most common genetic alterations in patients with juvenile polyposis are germline mutation of SMAD4 or BMPR1A, both genes implicated in the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signalling pathway. Cowden disease is caused by germline mutations of PTEN resulting in multiple hamartomas involving multiple different organs. Cronkite–Canada syndrome is a non-inherited polyposis syndrome of unknown pathogenesis.

Gastric carcinoma

Epidemiology of gastric carcinoma

Despite a steady decline of gastric carcinoma incidence at a rate of approximately 5% per year since the 1950s,46 gastric carcinoma is still the fourth most common carcinoma in the world, with one million people newly diagnosed per year, representing 8% of all new cancers diagnosed per year in the world. Age-standardised incidence rates of gastric carcinoma are twice as high in males as in females and show prominent geographical variation, ranging from 3.9 in Northern Africa to 42.4 in Eastern Asia per 100 000 males.47 Seventy-five per cent of all new gastric carcinoma cases are diagnosed in Asia. Gastric carcinoma is the second leading cause of cancer death in both sexes worldwide, being responsible for 10% of all cancer deaths. A male:female ratio of 2:1 has been reported for non-cardia gastric carcinoma in contrast to a male:female ratio of 5:1 for gastric cardia carcinoma.48

Aetiology and risk factors of gastric carcinoma

Ten per cent of gastric carcinomas show familial clustering, but only 1–3% of gastric carcinomas are related to identified inherited gastric carcinoma predisposition syndromes such as hereditary diffuse gastric carcinoma, hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome), familial adenomatous polyposis, Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, Li–Fraumeni syndrome, and familial breast and ovarian cancer.49,50

One of the defining characteristics of the hereditary diffuse gastric carcinoma syndrome (HDGC) is the presence of a germline CDH1 (E-cadherin) mutation.51 CDH1 mutations have been found in hereditary as well as sporadic diffuse-type gastric carcinomas, but not in intestinal-type gastric carcinomas. CDH1 mutations in sporadic diffuse-type gastric carcinoma cluster in exons 7–9, whereas CDH1 germline mutations are spread over the whole length of the gene in HDGC patients, making genetic testing very time consuming as the whole CDH1 gene might need to be sequenced.52 Patients diagnosed with HDGC have an increased risk of lobular breast cancer and signet-ring colon cancer, and should undergo appropriate surveillance for these diseases.53 The penetrance of the gene varies between 70% and 80%, and the lifetime risk of developing gastric carcinoma in mutation carriers is 67% in men and 83% in women. In order to identify patients that should be offered CDH1 mutation testing, including appropriate genetic counselling, the updated recommendations of the International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium (IGCLC) should be followed51 (Box 1.1).

The resection specimen should be worked up and reported according to the recommendations of the IGCLC.51

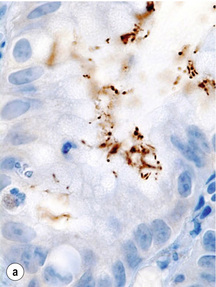

Helicobacter pylori infection increases the risk of gastric carcinoma up to sixfold and hence represents one of the most important environmental risk factors for the development of gastric carcinoma. Humans are the only known host for H. pylori that can colonise the body and the antrum (Fig. 1.5). The development of gastric carcinoma after H. pylori infection has been considered as a multistep process progressing from chronic active pan- or corpus predominant gastritis to increasing loss of gastric glands (atrophy), replacement of the normal mucosa by intestinal metaplasia and malignant transformation.54–56 Most H. pylori-infected individuals will remain asymptomatic and only 1–5% of the infected population will develop gastric carcinoma, a phenomenon that has been attributed to different bacterial strains, host-inflammatory genetic susceptibility and in particular the H. pylori virulence factors vacuolating cytotoxin antigen (VacA) and cytotoxin-associated gene A antigen (CagA).54,57,58

Figure 1.5 Helicobacter pylori. The Gram-negative, spiral-shaped, 2.5 to 5 μm long bacterium can be found on the gastric surface epithelium within the mucous layer. (a) Immunohistochemical staining demonstrates the organisms as brown rods. (b) In the modified Giemsa staining, the organisms appear light blue.

It has been estimated that 10% of gastric carcinomas are associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection.59 Considering the worldwide incidence of gastric carcinoma, EBV-associated gastric carcinoma is the largest group of carcinomas within all EBV-associated malignancies. In contrast to H. pylori, which has a role in the early stage of gastric carcinoma development as it binds to the surface of the normal gastric epithelial cell but cannot bind to the surface of gastric carcinoma cells, EBV is absent in normal or dysplastic gastric epithelial cells but present in all gastric carcinoma cells.60 For unknown reasons, EBV prevalence is higher in gastric stump cancer.61

The prominent geographical variation in gastric carcinoma incidence suggests that other environmental factors such as diet might play an important aetiological role. However, evidence for all areas like fruit and vegetable consumption, dietary supplementation with antioxidants such as vitamin C, dietary salt and nitroso compounds is still conflicting.62–64

A dose dependent relationship between smoking and gastric carcinoma risk has been shown in prospective studies and it has been estimated that 18% of gastric carcinomas in the European population were attributable to smoking.65 There is currently no conclusive evidence for an association between alcohol consumption and gastric carcinoma.66 An increased risk of gastric carcinoma after previous gastric surgery for benign peptic ulcer disease has been reported.67 Another potential source of gastric stump carcinoma is the Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy used to treat morbid obesity and gastric carcinoma after bariatric surgery has already been reported.

Lesions predisposing to gastric carcinoma

The natural history of sporadic gastric carcinoma is thought to be a multistep process. Correa postulated a sequence from chronic atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and gastric carcinoma based on histopathological findings68 (for more details, see Chapter 2). Ten years later, this model was expanded by Yasui et al.69 to include stepwise molecular alterations.

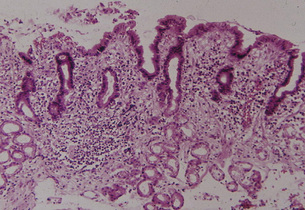

Chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia: Inflammation of the gastric mucosa is the result of bacterial infection (most commonly due to H. pylori infection), chemical agents (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), alcohol, bile reflux) or the consequence of an autoimmune process (i.e. autoimmune gastritis due to parietal cell antibodies). Depending on the underlying aetiology, chronic inflammation can result in (a) the shrinkage or complete disappearance of the typical gastric glands followed by replacement fibrosis of the lamina propria or (b) replacement of the native glands by metaplastic glands (i.e. intestinal and/or pseudopyloric metaplasia). In both conditions there is ‘atrophy’ (loss of appropriate glands), but only (b) is considered a condition with an increased risk of developing carcinoma (Fig. 1.6).

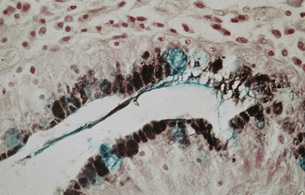

Two main types of intestinal metaplasia have been identified depending on whether the epithelium is similar to small bowel epithelium or large bowel epithelium and on the histochemical characteristics of the mucin. Type I is complete, small bowel type, positive for neutral mucin and sialomucin, and negative for sulfomucin; type II/III is incomplete, large bowel type, positive or negative for neutral mucin, and positive for sialomucin and sulfomucin (Fig. 1.7).

Figure 1.7 Intestinal metaplasia (type III). The pits show both large solitary and multiple smaller secretory vacuoles with the apical positions of the cells. Stained with Alcian Blue and High Iron Diamine.

Figure 1.8 (a) Borrmann classification for advanced cancers. Type I: polypoid with a broad base, may be superficially ulcerated. Type II: excavated ulcerated lesion with elevated borders, sharp margin with no definitive infiltration into adjacent mucosa. Type III: ulcerative, diffusely infiltrating base. Type IV: diffusely infiltrative thickening of the wall (linitis plastica). (b) Murakami classification for early cancers. Modified from Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma, 3rd English edn. Gastric Cancer 2011; 14(2):101–12.

Chronic gastric ulcer: Chronic gastric ulcers are typically located near the border of atrophic mucosa. If a chronic gastric ulcer is detected on endoscopy, it should be suspected of being neoplastic until histology has proven otherwise. Patients with gastric ulcer have an increased risk for gastric carcinoma as gastric ulcer and gastric carcinoma have the same risk factors. Five per cent of endoscopically benign ulcers eventually prove to be malignant. However, overall, less than 1% of all gastric carcinomas develop in pre-existing peptic ulcers.70

Gastric dysplasia: Gastric dysplasia (synonym: intraepithelial neoplasia) can have a flat, slightly depressed or polypoid growth pattern. In Europe and North America polypoid dysplasia is termed ‘adenoma’, whereas in Japan dysplasia with any growth pattern is called ‘adenoma’.

The prevalence of gastric dysplasia varies, depending on the underlying aetiology, between 20% in high risk areas and 4% in Western countries, where gastric carcinoma is less common.71 Dysplasia is more frequent in males, patients over 70 years of age, and most commonly affects the lesser curve and the antrum. Histologically, dysplasia is characterised by architectural as well as cytological atypia and is stratified into two grades, low and high. Low grade dysplasia progresses to adenocarcinoma in up 23% of cases within 10 months to 4 years, whereas malignant transformation of high grade dysplasia has been reported to occur in 60–80% of cases.

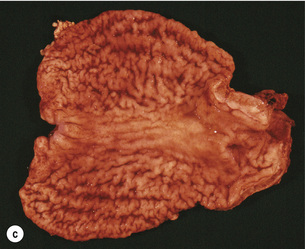

Early and advanced gastric carcinoma

Early gastric carcinoma is defined as adenocarcinoma limited to either the mucosa or submucosa irrespective of the presence of lymph node metastases.75 The term ‘early’ does not refer to the size or age of the lesion. Conversely, gastric carcinomas infiltrating into the muscularis propria and beyond are defined as ‘advanced’. These two categories of gastric carcinoma differ not only in prognosis, but also with respect to morphology and clinical aspects. Gastric carcinoma limited to the mucosa and submucosa has an excellent prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate exceeding 90% in Japan.76,77 Five-year survival rate of advanced gastric carcinomas, the most frequent presentation in the West, is around 23% when treated by surgery alone and around 36% when treatment includes perioperative chemotherapy.78 Retrospective and prospective long-term follow up studies showed that the tumour growth rate differs significantly between early and advanced carcinomas, and estimated a doubling time of early carcinomas of several years but less than a year for advanced carcinomas.79,80

The classification of the macroscopic growth pattern is applicable to radiological and endoscopic images as well as the macroscopic appearance of the resected specimen, and consistent use of this macroscopic classification can greatly improve the communication among surgeons, endoscopists, radiologists and pathologists, as demonstrated in Japan. Interestingly, approximately 10% of gastric carcinomas retain their endoscopic and radiological ‘early cancer’ appearance as they progress to advanced stage.82 This can lead to a potential underestimation of the ‘true’ clinical disease stage.

In Japan, approximately 2% of early gastric carcinomas recur after curative resection. Submucosal invasion, lymph node metastases and differentiated-type histology have been associated with increased risk of recurrence.83 Differentiated histology is a risk factor for recurrence as cancers with differentiated histology show a higher incidence of haematogenous spread compared to undifferentiated cancer that is more prone to recur in lymph nodes or serosa lined cavities. The incidence of lymph node metastases is 2–3% for intramucosal carcinomas84,85 and 20–30% for submucosal carcinomas.86

Morphological subtypes of gastric carcinoma

The histology of gastric carcinoma is characterised by marked heterogeneity. The variability of the histological appearance increases with increasing depth of infiltration into the wall and increasing age at time of diagnosis. As a result of this marked morphological diversity, a number of different classification systems have been advocated by different authors such as Laurén,35 Ming,87 Nakamura et al.,88 Mulligan,89 Goseki et al.,90 Carneiro91 and the World Health Organisation (WHO).12

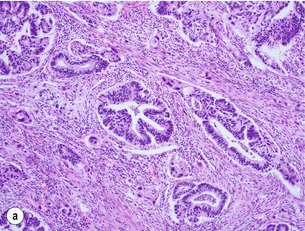

In Japan, the recommended histological typing is similar but not 100% identical to the WHO classification.92 In the West, 60–70% of gastric carcinomas are classified as intestinal-type according to Laurén (Fig. 1.10a), which is characterised by a predominance of glandular epithelium with cells similar to intestinal columnar cells. There is good cellular cohesion, the carcinoma is usually sharply demarcated and has a pushing margin according to Ming’s classification. Laurén’s diffuse-type is composed of scattered, poorly cohesive cells or small clusters of cells and is diffusely infiltrative (Fig. 1.10b). Cells may contain mucus and can have a signet ring cell appearance (Fig. 1.10c). Gastric carcinomas that consist of approximately 50% diffuse and 50% intestinal-type, solid type carcinomas and others that cannot be classified as diffuse or intestinal are called either indeterminate, unclassifiable or mixed. Intestinal-type carcinomas are more common in men over 60 years of age and in highrisk countries, are located in the antrum, are Borrmann type II and show metastases in the liver. In contrast, diffuse-type carcinomas are more common in younger females, have a similar incidence in most countries, are located predominantly in the proximal body of the stomach and show a linitis plastica type growth pattern with transperitoneal metastases.

Figure 1.10 (a) Intestinal-type carcinoma tubular subtype composed of irregularly sized and shaped glandular structures with mildly pleomorphic nuclei. However, this tumour is admixed with poorly differentiated tubular structures with large cells and bizarre shaped nuclei. (b) Diffuse-type carcinoma. Poorly cohesive single cells are diffusely infiltrating the smooth muscle wall. (c) Signet ring cell carcinoma. The neoplastic cells are characterised by large amounts of intracytoplasmic mucin (almost ‘clear’ cytoplasm) with eccentrically located and mostly flattened nuclei.

Gastric carcinomas are graded as well differentiated (more than 90% of the carcinoma consists of well-formed glands resembling intestinal epithelium), moderately differentiated (intermediate between well and poor) and poorly differentiated (highly irregular glands that may be difficult to be recognised as glands). According to the WHO classification,12 this grading system should only be applied for tubular- and papillary-type carcinomas, not for other morphological subtypes and not after neoadjuvant therapy. However, grading of tumour differentiation is prone to considerable interobserver variation and the value of the histological subtyping and/or tumour grading in predicting patient prognosis is still controversial.

Molecular pathology of gastric carcinoma

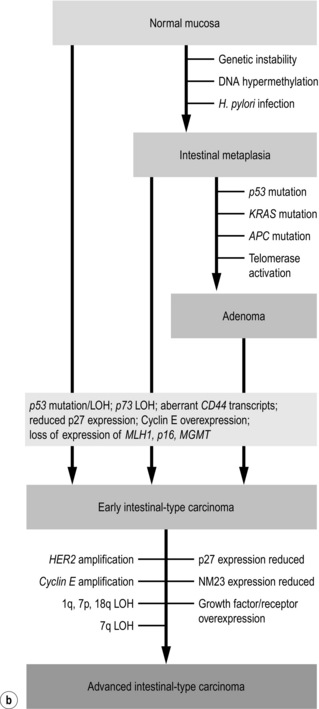

The first gene found to be amplified in gastric carcinoma was c-MYC in 1984,93 while the first oncogene discovered in gastric carcinoma was FGF4 in 1986.94 Ten years later, Yasui et al.69 proposed a multistep model of molecular alterations, refining the multistep model of histological changes proposed by Correa56 (Fig. 1.11). This refined model by Yasui et al. suggests that the two main morphological gastric carcinoma subtypes, intestinal and diffuse, are characterised by different underlying molecular mechanisms. However, some alterations such as genetic instability, hypermethylation and telomere reduction have been identified in both histological subtypes and therefore appear to occur during the early stages of cancer development. Others are supposedly unique or at least predominant in a particular histological subtype, such as CDH1 mutations in diffuse-type and KRAS mutations in intestinal-type gastric carcinoma.

c-MET is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor and was found to be amplified at higher frequency in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma compared to intestinal-type gastric carcinoma (39% vs. 19% gastric carcinoma).95 Overexpression of c-MET has been related to tumour stage.96 With the advent of c-MET inhibitors, the interest in this molecule has been revived and a very recent large study conducted in Korea demonstrated that c-MET was amplified in 21% of gastric carcinomas, identifying c-MET as a potential new drug target.97 Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) is another potential drug target and FGFR2 amplification has been detected in gastric carcinoma.

p53 is frequently inactivated in gastric carcinoma by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or mutations. p53 mutations have been identified in 60% of gastric carcinomas, with approximately equal frequency in different histological subtypes, and thus make it the most frequently mutated gene in gastric carcinoma.98 APC mutations have been observed in 30–40% of well and moderately differentiated intestinal-type gastric carcinomas and in less than 2% diffuse-type gastric carcinomas.99

Alterations (mutations or gene silencing by methylation) of any of the five human DNA mismatch repair genes, MSH2, MLH1, MSH6, PMS1 and PMS2, result in defective mismatch repair. Tumours with DNA mismatch repair deficiency show variations in the number of short tandem repeat units contained within microsatellites, a phenomenon called microsatellite instability. Cells with defective mismatch repair also display substantially elevated numbers of mutations thought to accelerate carcinogenesis. The reported frequency of microsatellite instability varies between 15% and 38% of gastric carcinomas, is higher in intestinal-type gastric carcinoma and is more common in cancers from older age females and cancers in the antrum.100

Neuroendocrine tumours of the stomach

The gastric mucosa contains several types of neuroendocrine cells, which produce neurotransmitter, neuromodulator or neuropeptide hormones and release them into the bloodstream. These cells are usually immunoreactive for chromogranin A and synaptophysin.101 Neuroendocrine tumours (previously known as ‘carcinoids’) arise most commonly from enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells. Hypergastrinaemia due to unregulated hormone release by a gastrinoma or due to hyperplasia of gastrin producing cells in the antrum secondary to achlorhydria is consistently associated with hyperplasia of the ECL cells.102 A multistep progression from simple hyperplasia through nodule formation to dysplasia and tumour formation is thought to occur.

The incidence of gastric neuroendocrine tumours has been increasing over the last decades and accounts for 6% of all gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours.103 Neuroendocrine tumours of the stomach are almost exclusively located in the body of the stomach.

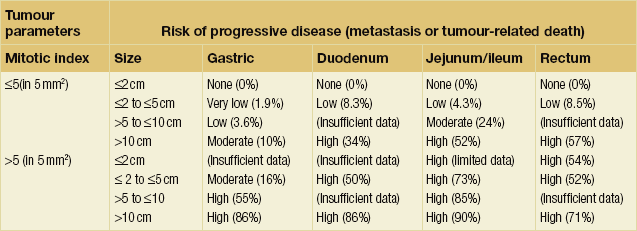

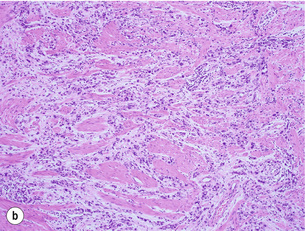

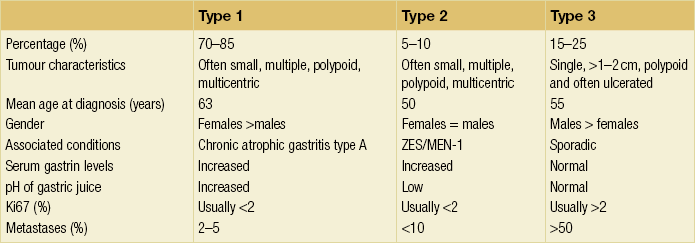

Three distinct types of neuroendocrine tumours can be distinguished based on their pathogenesis (Table 1.1):12

Table 1.1

Characteristics of gastric neuroendocrine tumours

MEN, multiple endocrine neoplasia; ZES, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome.

Reproduced from Massironi S, Sciola V, Spampatti MP et al. Gastric carcinoids: between underestimation and overtreatment. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:2177–83.

• Type 1. Multiple well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours affecting predominantly middle-aged females are associated with auto-immune chronic atrophic gastritis and pernicious anaemia due to auto-antibodies against parietal cells. This type is the most common type of gastric neuroendocrine tumour. Tumours tend to be limited to the submucosa. Metastases can be found in 7–12% of cases and are usually confined to the local lymph nodes. A reduction in the number of ECL cells can be achieved by treatment with octreotide.104

• Type 2. Neuroendocrine tumours associated with the Zollinger–Ellison syndrome (gastrinoma-related syndrome) in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 1 have no sex predilection. The tumours tend to be multicentric with minimal gastritis in the background, but both ECL hyperplasia and dysplasia are present. These tumours often extend deep into the muscle wall, have lymph node metastases and have occasionally caused death. The loss of the tumour suppressor gene MEN1 on chromosome 11q13 is seen in the majority of these tumours, a defect also found in those tumours of the gut, pancreas and parathyroid associated with MEN-1.105

• Type 3. Sporadic neuroendocrine tumours are neither associated with atrophic gastritis nor with MEN-1 syndrome. These tumours are usually solitary lesions that occur in middle-aged men. They tend to be larger (> 2 cm) and have a more aggressive behaviour. The background mucosa shows no evidence of atrophic gastritis and no evidence of neuroendocrine hyperplasia or dysplasia. Serosal infiltration with lymphatic and vascular invasion and liver metastasis with an accompanying carcinoid syndrome are common. Metastases are present in 52% of cases and approximately one third of patients will have died within 51 months.

Grade 1 neuroendocrine tumours have typically a Ki67 index below 2%, whereas grade 3 tumours are poorly differentiated, have a Ki67 index above 20%, show necrosis and are therefore classified as neuroendocrine carcinomas. Guidelines for the management of gastric neuroendocrine tumours have been updated very recently.106

Mesenchymal tumours of the stomach

With the exception of very small tumours, all GISTs have the potential to become malignant.

Lymphoma of the stomach

Any type of lymphoma can also occur in the gastrointestinal tract, which is the commonest extranodal site.12 Within the gastrointestinal tract, 50–75% of lymphomas are located in the stomach; 5–10% of all gastric malignancies are primary lymphomas. The two most common subtypes of primary gastric lymphomas are extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (so-called MALT lymphoma) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The incidence of primary gastric lymphoma is similar in men and women.

MALT lymphoma

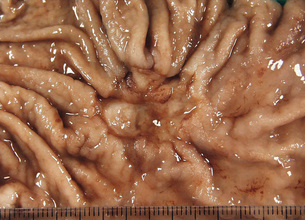

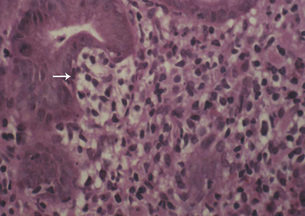

The majority of MALT lymphomas occur in patients over the age of 50 years, with equal sex distribution, who present clinically with symptoms suggesting a diagnosis of gastritis or peptic ulcer disease. The tumours appear macroscopically as an ill defined thickening of the mucosa with erosions, sometimes ulcerated (Fig. 1.12) and frequently multifocal. Gastric MALT lymphoma can spread to the regional nodes. MALT lymphoma is composed of neoplastic B cells that resemble follicle centre cells and are termed centrocyte-like, whereas other cells show plasma cell differentiation and occasionally there are blast cells. The characteristic lymphoepithelial lesion (Fig. 1.13) is composed of small to medium-sized tumour cells with irregular nuclei that infiltrate the pit epithelium. This lesion is not pathognomonic of a lymphoma as it can also be demonstrated in an H. pylori-associated gastritis, Sjögren’s syndrome and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

Most low grade MALT lymphomas are associated with disease confined to the gastric mucosa with slow dissemination. The favourable clinical behaviour may reflect the partial dependence on the H. pylori antigenic drive. The progression to the more common high grade MALT lymphoma is thought to require the acquisition of further genetic abnormalities.108 Gastric MALT lymphoma with the t(11;18)(q21;q21) translocation should be treated with chemotherapy or radiation, as H. pylori eradication alone is ineffective. The other lymphomas that are resistant to H. pylori eradication are those with abnormalities of the BCL10 locus or those associated with an autoimmune gastritis. These can be identified by strong nuclear staining with anti-BCL10 in the former and in the latter by staining with the product of the FAS oncogene. These non-responsive lymphomas can be treated surgically or in combination with chemoradiotherapy. The 5-year survival for localised cases is 90–100%. Continued follow up of these patients is recommended as it is now recognised that synchronous and metachronous adenocarcinomas can occur.109

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma

Primary gastric diffuse large B cell lymphoma is composed of B cells with a nuclear size equivalent to a macrophage nucleus of at least twice the size of a normal lymphocyte. Similar to MALT lymphoma, the neoplastic cells destroy the gastric glandular architecture. Up to 50% of diffuse large B cell lymphomas have foci of MALT lymphomas and regression of diffuse large B cell lymphoma after eradication of H. pylori has been reported. Macroscopically, this lymphoma appears as a large ulcerated mass mimicking advanced gastric carcinoma. Chromosomal translocations involving the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene locus are frequent in diffuse large cell lymphomas, resulting in deregulation of BCL6, BCL2 and MYC.110 In the presence of EBV, diffuse large B cell lymphomas are more likely to be resistant to chemoradiotherapy.111

References

1. Munoz, N., Crespi, M., Grassi, A., et al, Precursor lesions of oesophageal cancer in high-risk populations in Iran and China. Lancet 1982; 1:876–879. 6122101

2. Blot, W., McLaughlin, J., Fraumeni, J. Esophageal cancer. In: Schottenfeld D., Fraumeni J., eds. Cancer epidemiology and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006:697–706.

3. Boffetta, P., Hashibe, M., Alcohol and cancer. Lancet Oncol 2006; 7:149–156. 16455479

4. Leeuwenburgh, I., Haringsma, J., Van Dekken, H., et al, Long-term risk of oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal cancer in achalasia patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;243(Suppl. 2):7–10. 16782616

5. Swinson, C.M., Slavin, G., Coles, E.C., et al, Coeliac disease and malignancy. Lancet 1983; 1:111–115. 6129425

6. Chisholm, M., The association between webs, iron and post-cricoid carcinoma. Postgrad Med J 1974; 50:215–219. 4449772

7. Risk, J.M., Evans, K.E., Jones, J., et al, Characterization of a 500 kb region on 17q25 and the exclusion of candidate genes as the familial Tylosis Oesophageal Cancer (TOC) locus. Oncogene 2002; 21:6395–6402. 12214281

8. O’Mahony, M.Y., Ellis, J.P., Hellier, M., et al, Familial tylosis and carcinoma of the oesophagus. J R Soc Med 1984; 77:514–517. 6234394

9. Appelqvist, P., Salmo, M., Lye corrosion carcinoma of the esophagus: a review of 63 cases. Cancer 1980; 45:2655–2658. 7378999

10. Huang, B.S., Unni, K.K., Payne, W.S., Long-term survival following diverticulectomy for cancer in pharyngoesophageal (Zenker’s) diverticulum. Ann Thorac Surg 1984; 38:207–210. 6433819

11. Micke, O., Schafer, U., Glashorster, M., et al, Radiation-induced esophageal carcinoma 30 years after mediastinal irradiation: case report and review of the literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1999; 29:164–170. 10225701

12. World Health Organisation. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system, 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2010.

13. Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese classification of esophageal cancer, tenth edition: part I. Esophagus. 2009; 6:1–25.

14. Takubo, K., Aida, J., Sawabe, M., et al, Early squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus: the Japanese viewpoint. Histopathology 2007; 51:733–742. 17617215

15. Peters, C.J., Hardwick, R.H., Vowler, S.L., et al, Generation and validation of a revised classification for oesophageal and junctional adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2009; 96:724–733. 19526624

16. Ando, N., Ozawa, S., Kitagawa, Y., et al, Improvement in the results of surgical treatment of advanced squamous esophageal carcinoma during 15 consecutive years. Ann Surg 2000; 232:225–232. 10903602

17. Akiyama, H., Tsurumaru, M., Udagawa, H., et al, Radical lymph node dissection for cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg 1994; 220:364–373. 8092902

18. Sarbia, M., Porschen, R., Borchard, F., et al, Incidence and prognostic significance of vascular and neural invasion in squamous cell carcinomas of the esophagus. Int J Cancer 1995; 61:333–336. 7729944

19. Mandard, A.M., Dalibard, F., Mandard, J.C., et al, Pathologic assessment of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy of esophageal carcinoma. Clinicopathologic correlations. Cancer 1994; 73:2680–2686. 8194005

20. Bollschweiler, E., Holscher, A.H., Metzger, R., et al, Prognostic significance of a new grading system of lymph node morphology after neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92:2020–2027. 22115212

21. Chu, Q., Jaganmohan, S., Kelly, B., et al, Verrucous carcinoma of the esophagus: a rare variant of squamous cell carcinoma for which a preoperative diagnosis can be a difficult one to make. J La State Med Soc 2011; 163:251–253. 22272545

22. Handra-Luca, A., Terris, B., Couvelard, A., et al, Spindle cell squamous carcinoma of the oesophagus: an analysis of 17 cases, with new immunohistochemical evidence for a clonal origin. Histopathology 2001; 39:125–132. 11493328

23. Lauwers, G.Y., Grant, L.D., Scott, G.V., et al, Spindle cell squamous carcinoma of the esophagus: analysis of ploidy and tumor proliferative activity in a series of 13 cases. Hum Pathol 1998; 29:863–868. 9712430

24. Wang, G.Q., Abnet, C.C., Shen, Q., et al, Histological precursors of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from a 13 year prospective follow up study in a high risk population. Gut 2005; 54:187–192. 15647178

25. Crespi, M., Munoz, N., Grassi, A., et al, Precursor lesions of oesophageal cancer in a low-risk population in China: comparison with high-risk populations. Int J Cancer 1984; 34:599–602. 6500739

26. Lin, J., Beerm, D.G., Molecular biology of upper gastrointestinal malignancies. Semin Oncol 2004; 31:476–486. 15297940

27. Lagergren, J., Adenocarcinoma of oesophagus: what exactly is the size of the problem and who is at risk? Gut 2005; 54:i1–i5. 15711002

28. Dulai, G.S., Guha, S., Kahn, K.L., et al, Preoperative prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in esophageal adenocarcinoma: a systematic review. Gastroenterology 2002; 122:26–33. 11781277

29. Siewert, J.R., Stein, H.J., Classification of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg 1998; 85:1457–1459. 9823902

30. Barrett, N.R., Chronic peptic ulcer of the oesophagus and ‘oesophagitis’. Br J Surg 1950; 38:175–182. 14791960

31. Moersch, R.N., Ellis, F.H., Jr., McDonald, J.R., Pathologic changes occurring in severe reflux esophagitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1959; 108:476–484. 13635268

32. Hayward, J., The treatment of fibrous stricture of the oesophagus associated with hiatal hernia. Thorax 1961; 16:45–55. 13712531

33. Bremner, C.G., Lynch, V.P., Ellis, F.H., Jr., Barrett’s esophagus: congenital or acquired? An experimental study of esophageal mucosal regeneration in the dog. Surgery 1970; 68:209–216. 10483471

34. Haggitt, R.C., Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma. Hum Pathol 1994; 25:982–993. 7927321

35. Lauren, P., The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1965; 64:31–49. 14320675

36. Abraham, S.C., Krasinskas, A.M., Correa, A.M., et al, Duplication of the muscularis mucosae in Barrett esophagus: an underrecognized feature and its implication for staging of adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2007; 31:1719–1725. 18059229

37. Na, Y.J., Shim, K.N., Kang, M.J., et al, Primary esophageal adenoid cystic carcinoma. Gut Liver 2007; 1:178–181. 20485637

38. Bianchi, L.K., Burke, C.A., Bennett, A.E., et al, Fundic gland polyp dysplasia is common in familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:180–185. 18237868

39. Carmack, S.W., Genta, R.M., Schuler, C.M., et al, The current spectrum of gastric polyps: a 1-year national study of over 120,000 patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104:1524–1532. 19491866

40. Stolte, M., Vieth, M., Ebert, M.P., High-grade dysplasia in sporadic fundic gland polyps: clinically relevant or not? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 15:1153–1156. 14560146

41. Abraham, S.C., Nobukawa, B., Giardiello, F.M., et al, Sporadic fundic gland polyps: common gastric polyps arising through activating mutations in the beta-catenin gene. Am J Pathol 2001; 158:1005–1010. 11238048

42. Ohkusa, T., Takashimizu, I., Fujiki, K., et al, Disappearance of hyperplastic polyps in the stomach after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. A randomized, clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1998; 129:712–715. 9841603

43. Zea-Iriarte, W.L., Sekine, I., Itsuno, M., et al, Carcinoma in gastric hyperplastic polyps. A phenotypic study. Dig Dis Sci 1996; 41:377–386. 8601386

44. Kolodziejczyk, P., Yao, T., Oya, M., et al, Long-term follow-up study of patients with gastric adenomas with malignant transformation. An immunohistochemical and histochemical analysis. Cancer 1994; 74:2896–2907. 7954254

45. Giardiello, F.M., Brensinger, J.D., Tersmette, A.C., et al, Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology 2000; 119:1447–1453. 11113065

46. Howson, C.P., Hiyama, T., Wynder, E.L., The decline in gastric cancer: epidemiology of an unplanned triumph. Epidemiol Rev 1986; 8:1–27. 3533579

47. Ferlay, J., Shin, H.R., Bray, F., et al, Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010; 127:2893–2917. 21351269

48. El-Serag, H.B., Mason, A.C., Petersen, N., et al, Epidemiological differences between adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia in the USA. Gut 2002; 50:368–372. 11839716

49. Zanghieri, G., Di Gregorio, C., Sacchetti, C., et al, Familial occurrence of gastric cancer in the 2-year experience of a population-based registry. Cancer 1990; 66:2047–2051. 2224804

50. Palli, D., Galli, M., Caporaso, N.E., et al, Family history and risk of stomach cancer in Italy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1994; 3:15–18. 8118379

51. Fitzgerald, R.C., Hardwick, R., Huntsman, D., et al, Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated consensus guidelines for clinical management and directions for future research. J Med Genet 2010; 47:436–444. 20591882

52. Oliveira, C., Suriano, G., Ferreira, P., et al, Genetic screening for familial gastric cancer. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 2004; 2:51–64. 20233471

53. Pharoah, P.D., Guilford, P., Caldas, C., Incidence of gastric cancer and breast cancer in CDH1 (E-cadherin) mutation carriers from hereditary diffuse gastric cancer families. Gastroenterology 2001; 121:1348–1353. 11729114

54. Suzuki, H., Iwasaki, E., Hibi, T., Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2009; 12:79–87. 19562461

55. Correa, P., Haenszel, W., Cuello, C., et al, A model for gastric cancer epidemiology. Lancet 1975; 2:58–60. 49653

56. Correa, P., Helicobacter pylori and gastric carcinogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(Suppl. 1):S37–S43. 7762738

57. Peek, R.M., Jr., Blaser, M.J., Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat Rev Cancer 2002; 2:28–37. 11902583

58. Atherton, J.C., Peek, R.M., Jr., Tham, K.T., et al, Clinical and pathological importance of heterogeneity in vacA, the vacuolating cytotoxin gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology 1997; 112:92–99. 8978347

59. Fukayama, M., Ushiku, T., Epstein–Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract 2011; 207:529–537. 21944426

60. Tokunaga, M., Land, C.E., Uemura, Y., et al, Epstein–Barr virus in gastric carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1993; 143:1250–1254. 8238241

61. Zur Hausen, A., van Rees, B.P., van Beek, J., et al, Epstein–Barr virus in gastric carcinomas and gastric stump carcinomas: a late event in gastric carcinogenesis. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57:487–491. 15113855

62. Tsugane, S., Salt, salted food intake, and risk of gastric cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Sci 2005; 96:1–6. 15649247

63. Gonzalez, C.A., Pera, G., Agudo, A., et al, Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of stomach and oesophagus adenocarcinoma in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-EURGAST). Int J Cancer 2006; 118:2559–2566. 16380980

64. Bjelakovic, G., Nikolova, D., Simonetti, R.G., et al, Antioxidant supplements for preventing gastrointestinal cancers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; CD004183. 18677777

65. Gonzalez, C.A., Pera, G., Agudo, A., et al, Smoking and the risk of gastric cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Int J Cancer 2003; 107:629–634. 14520702

66. Franceschi, S., La Vecchia, C., Alcohol and the risk of cancers of the stomach and colon–rectum. Dig Dis 1994; 12:276–289. 7882548

67. Stalnikowicz, R., Benbassat, J., Risk of gastric cancer after gastric surgery for benign disorders. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150:2022–2026. 2222087

68. Correa, P., A human model of gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 1988; 48:3554–3560. 3288329

69. Yasui, W., Yokozaki, H., Shimamoto, F., et al, Molecular-pathological diagnosis of gastrointestinal tissues and its contribution to cancer histopathology. Pathol Int 1999; 49:763–774. 10504547

70. Lee, S., Iida, M., Yao, T., et al, Long-term follow-up of 2529 patients reveals gastric ulcers rarely become malignant. Dig Dis Sci 1990; 35:763–768. 2344810

71. Farinati, F., Rugge, M., Di Mario, F., et al, Early and advanced gastric cancer in the follow-up of moderate and severe gastric dysplasia patients. A prospective study. I.G.G.E.D. – Interdisciplinary Group on Gastric Epithelial Dysplasia. Endoscopy 1993; 25:261–264. 8330542

72. Schlemper, R.J., Riddell, R.H., Kato, Y., et al, The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut 2000; 47:251–255. 10896917

73. Rugge, M., Correa, P., Dixon, M.F., et al, Gastric dysplasia: the Padova international classification. Am J Surg Pathol 2000; 24:167–176. 10680883

74. Dixon, M.F., Gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia: Vienna revisited. Gut 2002; 51:130–131. 12077106

75. UICC. TNM classification of malignant tumors, 7th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

76. Everett, S.M., Axon, A.T., Early gastric cancer in Europe. Gut 1997; 41:142–150. 9301490

77. Hirota, T., Ming, S.C., Itabashi, M. Pathology of early gastric cancer. In: Nishi M., Ichikawa H., Nakajima Y., eds. Gastric cancer. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag; 1993:66–85.

78. Cunningham, D., Allum, W.H., Stenning, S.P., et al, Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:11–20. 16822992

79. Kohli, Y., Kawai, K., Fujita, S., Analytical studies on growth of human gastric cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol 1981; 3:129–133. 6895643

80. Tsukuma, H., Oshima, A., Narahara, H., et al, Natural history of early gastric cancer: a non-concurrent, long term, follow up study. Gut 2000; 47:618–621. 11034575

81. Borrmann, R. Handbuch der speziellen pathologischen Anatomie und Histologie. In: von Henke F., Lubarch O., eds. IV/erster Teil. Berlin: Julius Springer Verlag; 1926:864–871.

82. Mori, M., Adachi, Y., Nakamura, K., et al, Advanced gastric carcinoma simulating early gastric carcinoma. Cancer 1990; 65:1033–1040. 2297652

83. Saka, M., Katai, H., Fukagawa, T., et al, Recurrence in early gastric cancer with lymph node metastasis. Gastric Cancer 2008; 11:214–218. 19132483

84. Yamao, T., Shirao, K., Ono, H., et al, Risk factors for lymph node metastasis from intramucosal gastric carcinoma. Cancer 1996; 77:602–606. 8616749

85. Hirasawa, T., Gotoda, T., Miyata, S., et al, Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2009; 12:148–152. 19890694

86. Tajima, Y., Murakami, M., Yamazaki, K., et al, Risk factors for lymph node metastasis from gastric cancers with submucosal invasion. Ann Surg Oncol 2010; 17:1597–1604. 20131014

87. Ming, S.C., Gastric carcinoma. A pathobiological classification. Cancer 1977; 39:2475–2485. 872047

88. Nakamura, K., Sugano, H., Takagi, K., Carcinoma of the stomach in incipient phase: its histogenesis and histological appearances. Gann 1968; 59:251–258. 5726267

89. Mulligan, R.M., Histogenesis and biologic behavior of gastric carcinoma. Pathol Annu 1972; 7:349–415. 4557936

90. Goseki, N., Takizawa, T., Koike, M., Differences in the mode of the extension of gastric cancer classified by histological type: new histological classification of gastric carcinoma. Gut 1992; 33:606–612. 1377153

91. Carneiro, F. Classification of gastric carcinoms. Curr Diagn Pathol. 1997; 4:51–59.

92. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma, 3rd English edn. Gastric Cancer 2011; 14:101–112. 21573743

93. Nakasato, F., Sakamoto, H., Mori, M., et al, Amplification of the c-myc oncogene in human stomach cancers. Gann 1984; 75:737–742. 6500230

94. Sakamoto, H., Mori, M., Taira, M., et al, Transforming gene from human stomach cancers and a noncancerous portion of stomach mucosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986; 83:3997–4001. 3459165

95. Kuniyasu, H., Yasui, W., Kitadai, Y., et al, Frequent amplification of the c-met gene in scirrhous type stomach cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992; 189:227–232. 1333188

96. Kuniyasu, H., Yasui, W., Yokozaki, H., et al, Aberrant expression of c-met mRNA in human gastric carcinomas. Int J Cancer 1993; 55:72–75. 8344755

97. Lee, J., Seo, J.W., Jun, H.J., et al, Impact of MET amplification on gastric cancer: possible roles as a novel prognostic marker and a potential therapeutic target. Oncol Rep 2011; 25:1517–1524. 21424128

98. Yokozaki, H., Kuniyasu, H., Kitadai, Y., et al, p53 point mutations in primary human gastric carcinomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1992; 119:67–70. 1429828

99. Nakatsuru, S., Yanagisawa, A., Ichii, S., et al, Somatic mutation of the APC gene in gastric cancer: frequent mutations in very well differentiated adenocarcinoma and signet-ring cell carcinoma. Hum Mol Gen 1992; 1:559–563. 1338691

100. Wirtz, H.C., Mueller, W., Noguchi, T., et al, Prognostic value and clinicopathological profile of microsatellite instability in gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res 1998; 4:1749–1754. 9676851

101. Fahrenkamp, A.G., Wibbeke, C., Winde, G., et al, Immunohistochemical distribution of chromogranins A and B and secretogranin II in neuroendocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract. Virchows Arch 1995; 426:361–367. 7599788

102. Bordi C, D’Adda T, Azzoni C, et al. Hypergastrinemia and gastric enterochromaffin-like cells. Am J Surg Pathol 19(Suppl. 1):S8–19.

103. Modlin, I.M., Lye, K.D., Kidd, M., A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 2003; 97:934–959. 12569593

104. Ferraro, G., Annibale, B., Marignani, M., et al, Effectiveness of octreotide in controlling fasting hypergastrinemia and related enterochromaffin-like cell growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:677–683. 8636288

105. Debelenko, L.V., Emmert-Buck, M.R., Zhuang, Z., et al, The multiple endocrine neoplasia type I gene locus is involved in the pathogenesis of type II gastric carcinoids. Gastroenterology 1997; 113:773–781. 9287968

106. Ramage, J.K., Ahmed, A., Ardill, J., et al, Guidelines for the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine (including carcinoid) tumours (NETs). Gut 2012; 61:6–32. 22052063

107. Miettinen, M., Lasota, J., Histopathology of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Surg Oncol 2011; 104:865–873. 22069171

108. Zucca, E., Bertoni, F., Roggero, E., et al, Molecular analysis of the progression from Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic gastritis to mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma of the stomach. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:804–810. 9504941

109. Bacon, C.M., Du, M.Q., Dogan, A., Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: a practical guide for pathologists. J Clin Pathol 2007; 60:361–372. 16950858

110. Nakamura, S., Ye, H., Bacon, C.M., et al, Translocations involving the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene locus predict better survival in gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14:3002–3010. 18445693

111. Yoshino, T., Nakamura, S., Matsuno, Y., et al, Epstein–Barr virus involvement is a predictive factor for the resistance to chemoradiotherapy of gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci 2006; 97:163–166. 16441428