Chapter 21 Pathology

The purpose of medical imaging is to demonstrate the presence or absence of disease, so it is important for imaging practitioners to have some understanding of the types they might encounter.

The purpose of medical imaging is to demonstrate the presence or absence of disease, so it is important for imaging practitioners to have some understanding of the types they might encounter. Many diseases share common pathological processes relating to the causation and progression of the illness.

Many diseases share common pathological processes relating to the causation and progression of the illness. Understanding these general concepts in pathology can aid in the understanding of diseases specific to particular regions of the body.

Understanding these general concepts in pathology can aid in the understanding of diseases specific to particular regions of the body.INFECTION

Infection occurs when microorganisms multiply in tissues where they are normally absent or present in only small numbers. Those that cause disease are described as pathogenic (Table 21.1). The types of microorganism involved in infection include bacteria, viruses, yeast, fungi and protozoa.

| Disease | Organism and type | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis (TB) | Mycobacterium tuberculosis (bacterial) | Pulmonary or other organ infection resulting in chronic inflammation and tissue destruction |

| Cholera | Vibrio cholera (bacterial) | Severe diarrhoea |

| Pneumonia | Streptococcus pneumoniae and others (bacterial) | Pulmonary inflammation with fever |

| Osteomyelitis | Staphylococcus aureus and others (bacterial) | Often chronic bone infection resulting in pain and swelling |

| Gangrene | Clostridium perfringens (bacterial) | Severe tissue destruction resulting in tissue death and putrefaction |

| Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Destruction of T lymphocytes resulting in increased susceptibility to infection and development of rare tumours; e.g. Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Influenza | Influenza virus | Severe respiratory tract infection. Potentially fatal depending on the strain |

| Squamous epithelial tumours | Human papilloma virus | Malignant transformation of infected squamous epithelium, especially in the cervix |

| Viral hepatitis | Hepatitis B virus and others | Liver inflammation and potentially fatal |

| Pneumonia | Pneumocystis carinii (fungus) | Another cause of pneumonia, particularly in the immunocompromised; e.g. AIDS |

| Aspergillosis | Aspergillus fumigatus (fungus) | Chronic lung infection |

| Thrush | Candida albicans (yeast) | Mucous membrane lesions |

| Malaria | Plasmodium (protozoa) | Fever, anaemia, liver, spleen and lymph node enlargement. Potentially fatal |

INFLAMMATION

Inflammation may be of rapid (acute) or slow (chronic) onset.

ACUTE INFLAMMATION

Acute inflammation displays typical features:

CHRONIC INFLAMMATION

CARCINOGENESIS

Tissues that are growing or that have to replace cells lost or damaged as part of their normal function will show rapid cell division; in other tissues cell division will be very slow. In both cases the process is highly coordinated to ensure that the tissue is renewed in a way appropriate to itsfunction. Sometimes this careful coordination is lost and a cell may begin to divide more frequently than normal. As a result a mass of abnormal tissue may form which may be referred to as a neoplasm or tumour. The transformation of normal tissues or benign tumours into cancer is called carcinogenesis. Box 21.1 explains some of the terminology relating to tumours.

CANCER INCIDENCE

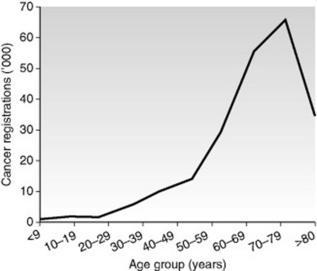

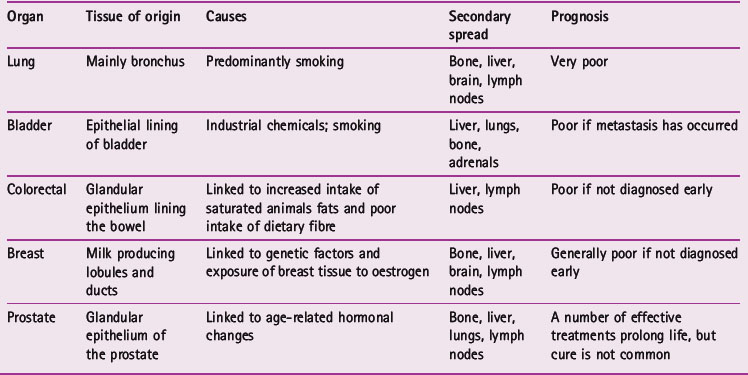

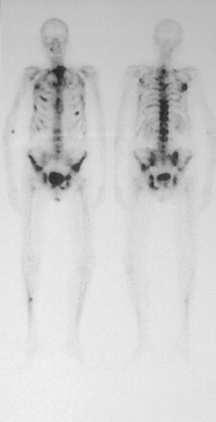

Cancer incidence increases with age (Fig. 21.1). The transformation of a normal cell into a cell that will form a tumour is primarily a genetic event, but this may be triggered by environmental factors. Cells from older people have had more time to experience the environmental factors that can lead to carcinogenesis and this may explain the increasing incidence with age. Table 21.2 gives details of some commonly seen cancers.

TUMOUR BEHAVIOUR

Malignant tumours

The grading and staging of malignant tumours

The prognosis of a person’s cancer is determined by both its grade and its stage. Grade refers to how well differentiated the tumour cells are; that is, how much like the tissue of origin they are. Poorly differentiated cells that have lost the particular characteristics of the organ from which they arise tend to form more aggressive tumours. Stage is determined by the size of the primary tumour and the degree of spread to local or remote organs and lymph nodes. Table 21.3 explains the staging scheme used for breast cancer.

Table 21.3 The main staging systems used to assess the extent of spread of breast carcinomas

| Stage | Extent of spread |

|---|---|

| International classification | |

| I | Lump with slight tethering to skin, but node negative |

| II | Lump with lymph node metastasis or skin tethering |

| III | Tumour which is extensively adherent to skin and/or underlying muscles, or ulcerating or lymph nodes are fixed |

| IV | Distant metastases |

| TNM | |

| T1 | Tumour 20 mm or less; no fixation or nipple retraction. Includes Paget’s disease |

| T2 | Tumour 20–50 mm, or less than 20 mm but with tethering |

| T3 | Tumour greater than 50 mm but less than 100 mm; or less than 50 mm but with infiltration, ulceration or fixation |

| T4 | Any tumour with ulceration or infiltration wide of it, or chest wall fixation, or greater than 100 mm in diameter |

| N0 | Node-negative |

| N1 | Axillary nodes mobile |

| N2 | Axillary nodes fixed |

| N3 | Supraclavicular nodes or oedema of arm |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

SKELETAL SYSTEM

ARTHRITIS

As a result of these changes, those with osteoarthritis may experience pain on movement, stiffness and joint instability. If this becomes severe it may be necessary to perform a total joint replacement (Fig. 21.2).

PAGET’S DISEASE

Paget’s is a fairly common disease affecting the elderly, arising from a disordering of normal bone turnover. Affected bones are characterised by an increase in bone synthesis, resulting in a thickened and sclerotic ‘cotton wool’ appearance radiographically. Paget’s usually affects the pelvis, skull and long bones, often progressing from one end towards the centre. Weight-bearing bones affected by Paget’s, such as the femur and tibia, can become bowed (Fig. 21.4). When the skull is affected there may be encroachment on the cranial nerve foramina, causing various neurological symptoms including vertigo, blindness and deafness.

BONE TUMOURS

Figure 21.5 Osteosarcoma in the proximal tibia, showing spiculated reactive bone growth under the periosteum.

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

ISCHAEMIA AND INFARCTION

Ischaemia is the reduction or loss of blood supply to a part of the body.

An infarct is a region of tissue where the cells have died due to ischaemia.

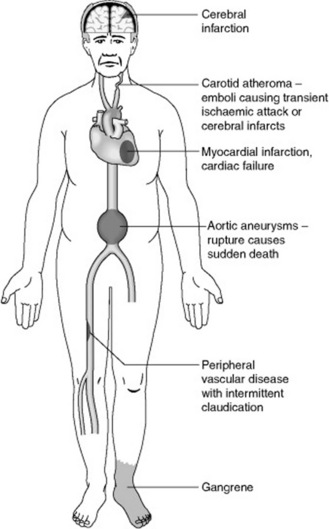

The main cause of ischaemia and infarction is atherosclerosis. This is the gradual accumulation of fatty deposits (atheroma) on the inner surface of an artery, which will cause narrowing (stenosis) and ultimately block it (occlusion) (Fig. 21.7). Atherosclerosis is associated with high levels of cholesterol and other lipids (fats) in the blood, smoking and elevated blood pressure. Arteries that have atherosclerosis are more prone to developing blood clots and this may cause a stenosed vesselto become occluded. Figure 21.8 shows possible complications of atherosclerosis.

THROMBOSIS

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

This occurs in the deep veins of the lower limbs, often as a result of slow blood flow associated with immobility; for example on long journeys or postoperatively. The return of blood from the limbs to the heart is impeded by the blockage of the veins and the leg may become red, swollen and tender.

HEART FAILURE

When the pumping capacity of the heart does not meet the needs of the body it is said to be in failure. Heart failure may affect the left, right or both ventricles and usually leads to their enlargement and accumulation of fluid in the tissues that feed blood to them (Fig. 21.9).

HEART VALVE DISEASE

The greatest clinical significance is attached to disease of the mitral and aortic valves:

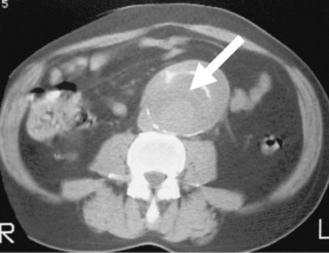

ANEURYSM

An aneurysm is an abnormal enlargement of the diameter of an artery, usually associated with atherosclerosis. The vessel wall may become thin, weakened and more liable to rupture. Common sites for aneurysm are the aorta and other large arteries (Fig. 21.10). Rupture of a large artery is very serious because of the possibility of fatal haemorrhage.

RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE (COPD)

COPD is a term describing the presence of chronic bronchitis and emphysema simultaneously. A diagnosis of chronic bronchitis is made on clinical grounds when a chronic productive cough exists for at least 3 months of the year over two consecutive years. It has the following features:

Emphysema is also present to a variable degree in COPD. In emphysema:

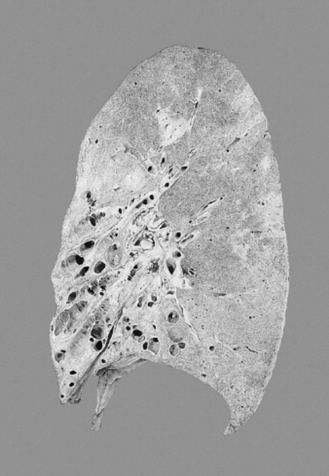

BRONCHIECTASIS

Bronchiectasis is characterised by permanent abnormal dilatation of the bronchi (Fig. 21.11). Patients experience a chronic cough, producing large amounts of sputum and having difficulty in breathing (dyspnoea). It is caused by severe, recurrent or chronic infection. Associated inflammation leads to scarring and destruction of the airways, which become permanently enlarged.

TUBERCULOSIS (TB)

The primary focus of infection is normally the mid/upper zone of the lungs where pulmonary lesions known as Ghon complexes form. In this primary stage of infection the disease is usually clinically silent, as the bacteria are walled off within a granuloma. The bacteria may migrate from theinitial infection site to the lung apices (secondary tuberculosis) or become widely disseminated throughout the lungs and other organs (miliary tuberculosis).

PNEUMOTHORAX

A tension pneumothorax describes a situation where air is pulled into the pleural space on inspiration that cannot escape on expiration. This is often associated with an injury penetrating the thoracic wall. The result is a steadily increasing compression of the lung on the affected side causing it to collapse, and the mediastinum is pushed away from the midline (Fig. 21.12). This obstructs venous return to the heart and decreases cardiac output. It is a medical emergency that requires urgent placement of a chest drain.

PLEURAL EFFUSION

In certain pathological conditions the amount of serous fluid secreted into the pleural space increases. These include heart failure, bacterial pneumonia, lung cancer and tuberculosis. In the erect position the fluid accumulates at the lung bases and may be identified on the chest radiograph when the volume exceeds 300 ml. If the volume of pleural effusion is very large it will interfere with respiration and must be removed via a chest drain (Fig. 21.13).

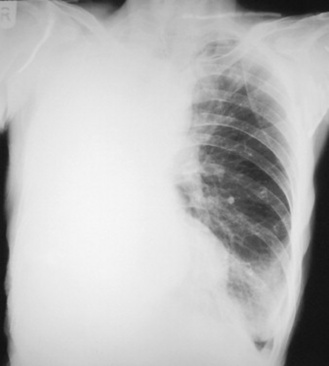

LUNG CANCER

Primary lung tumours

Lung cancer is the most common malignant tumour (Fig. 21.14). There are different types of lung cancer, as the tumour may arise from different cell types, though they are usually cells within the bronchi. The prognosis and treatments options are dependent on whether it is a non-small cell lung cancer (85%) or small cell lung cancer (15%).

DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

Disorders of the gastrointestinal tract can have profound effects on the sufferer. Diseases may be chronic and disabling, and in some cases life-threatening. The psychological effects of having problem bowels can also be a significant factor in an individual’s ability to cope with their disease.

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease may occur anywhere in the alimentary tract but is most common in the terminal portion of the ileum (Fig. 21.16). Abdominal pain is often present. Deep linear ulcers form, which may extend through the full thickness of the wall, and this may result in the formation of fistulae between adjacent bowel loops or between the bowel and the skin surface, particularly around the anus. Whereas ulcerative colitis forms a continuous zone of diseased bowel, Crohn’s may affect several separate portions, hence the term ‘skip lesions’. The bowel develops a thickened and fibrosed wall whilst the lumen becomes stenosed, which may lead to bowel obstruction.

INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION

Abdominal radiographs are commonly requested for investigating suspected intestinal obstruction. Obstruction may be complete or partial. The bowel proximal to the obstruction accumulates fluid and gas, causing the typical radiographic appearance of dilated bowel loops. Deciding whether the obstruction is in the large or small bowel can be made on the basis of the distribution, diameter and shape of the gas pattern (Fig. 21.17).

Causes of intestinal obstruction:

DIVERTICULAR DISEASE

As they are open-ended towards the bowel lumen, diverticula are filled with faeces, which can become stagnant and inflamed (Fig. 21.18). The presence of diverticula is called diverticulosis; when one or more are inflamed the condition is called diverticulitis. This is experienced as abdominal pain and fever. Complications of diverticulitis include abscess formation and perforation.

PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE (PUD)

Bleeding from peptic ulcers may result in sufficient blood loss to cause anaemia, and may also be evidenced by digested blood in the stool (melaena). Peptic ulcers may be sufficiently severe to perforate the bowel wall, allowing bowel contents and gas to escape into the peritoneal cavity. Erect chest X-rays are often requested in suspectedpeptic ulcer perforation to identify gas collected beneath the diaphragm, which is indicative of this condition.

COLORECTAL CANCER

Bowel cancers may appear as a fungating mass with an ulcerated centre or as a complete ring of tumour growth. The latter is associated with marked fibrosis that causes the bowel to constrict, forming an annular stricture. This type gives the typical apple core appearance shown by barium enema (Fig. 21.19).

URINARY SYSTEM

The kidneys are vital to good health, eliminating unwanted products of metabolism and helping to maintain a stable chemical environment within the body through homeostasis. The purpose of the remainder of the urinary tract is essentially of urine storage or elimination. Disorders of the urinary tract can cause serious and sometimes life-threatening disease.

UROLITHIASIS

NERVOUS SYSTEM

CEREBROVASCULAR EVENT (STROKE)

Infarction

Brain infarction occurs when part of the brain suffers a critical reduction in blood supply to the extent that the affected region dies. This may be caused by:

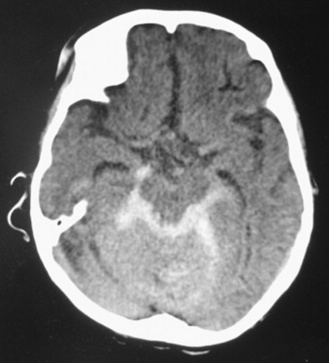

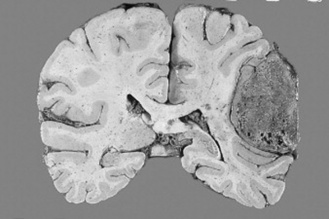

Haemorrhage

Intracerebral haemorrhage results in a haematoma that takes up space within the brain matter, causing increased intracranial pressure and distortion of the brain structure. In SAH blood accumulates inside the arachnoid layer of the meninges, giving rise to increased intracranial pressure (Fig. 21.21). As with intracerebral haemorrhage there is distortion of the brain structure. Irritation of the arteries by the free blood may also cause arterial spasm and infarct.

SPINAL CORD AND NERVE COMPRESSION

Causes of compression

Intervertebral disc herniation

The intervertebral disc consists of a tough outer ring of dense connective tissue (the annulus fibrosus) surrounding a soft jelly-like centre (the nucleus pulposus). It allows flexibility in the spine and acts as a shock absorber. Sometimes the outerring may be damaged and part of the nucleus pulposus herniates through the weakness in the annulus fibrosus. This herniation can cause compression of the spinal cord or the spinal nerve roots. Depending on its severity, the disc may need surgery to remove the parts that are compressing the nerve. This condition is shown very well by magnetic resonance imaging but not radiography.

Tumour infiltration

Metastases to the vertebral column are usually the cause of the most severe neurological effects (Fig. 21.22). Infiltration of the vertebral bodies leads to severe weakening and collapse. The fragments extrude posteriorly and cause compression of the cord.

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disabling neurological disorder resulting from damage to the myelin coating of nerve cells in the central nervous system. It usually presents between the ages of 20 and 40. Patients with MS suffer from loss of normal function in certain parts of the body due to disruption of the nerve signals to and from the brain. These symptoms may be episodic, only presenting during a relapse, or permanent. The damaged areas of the nerves form scar tissue called plaques; these are well shown by MRI.

BRAIN TUMOURS

Primary brain tumours

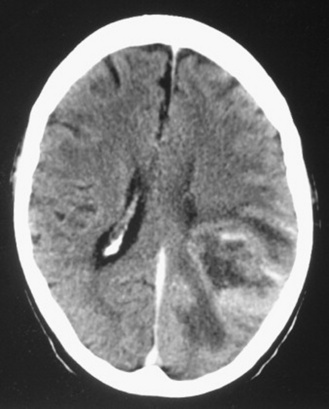

These tumours may grow slowly or rapidly and spread by local extension into surrounding tissues. They do not metastasise to other organs. The effect they have on the individual is dependent on where they are located in the brain (Fig. 21.23). Tumours in the frontal lobe may affect personality and mood; those in the temporal lobe may affect coordination speech and memory. The precise effect depends on the function of the brain tissue damaged and the size of the tumour. Because they arise from the brain tissue itself, they are referred to as intrinsic tumours.

Figure 21.23 Computed tomography showing an enhancing brain tumour within the left cerebral hemisphere.

Extrinsic tumours develop from the tissues covering the brain and spinal cord. A meningioma is a tumour of the meninges. They may grow large and cause considerable distortion and compression of the brain; however, they are usually benign and do not infiltrate the brain tissue. Surgery is usually the first option for removal, and this is often completely curative (Fig. 21.24).

Copstead LC, Banasik JL. Pathophysiology, 3rd edn. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders, 2005.

Kumar PJ, Clark ML. Clinical medicine, 6th edn. Edinburgh: Saunders, 2005.

Reid R, Roberts F. Pathology illustrated, 6th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

This book provides a very user-friendly text, which is concise and well presented..

Underwood JCE. General and systematic pathology, 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.