CHAPTER 20 Patellofemoral Arthroplasty

Indications and Outcomes

Initial management of patellofemoral arthritis will consist of conservative measures, including appropriate physical therapy to restore patellofemoral mechanics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications combined with injection treatment, weight reduction, and activity modification. When nonsurgical treatment is ineffective and pain becomes disabling, surgical alternatives may be considered.

Initial management of patellofemoral arthritis will consist of conservative measures, including appropriate physical therapy to restore patellofemoral mechanics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications combined with injection treatment, weight reduction, and activity modification. When nonsurgical treatment is ineffective and pain becomes disabling, surgical alternatives may be considered. Patellofemoral arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty remain the most predictable treatment alternatives for isolated degenerative arthritis of the patellofemoral joint. With the development of new implant designs and improved surgical technique, patellofemoral arthroplasty can provide a more conservative approach with the ability to retain the medial and lateral menisci, as well as the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments.

Patellofemoral arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty remain the most predictable treatment alternatives for isolated degenerative arthritis of the patellofemoral joint. With the development of new implant designs and improved surgical technique, patellofemoral arthroplasty can provide a more conservative approach with the ability to retain the medial and lateral menisci, as well as the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments. Appropriate patient selection remains the key factor in achieving high long-term success rates with patellofemoral arthroplasty. The procedure can be considered in patients with primary end-stage osteoarthritis, isolated to the patellofemoral joint. In addition, patients with posttraumatic degenerative arthritis or advanced chondromalacia of either the patellar surface, trochlear surface, or both can also be considered candidates for patellofemoral arthroplasty.

Appropriate patient selection remains the key factor in achieving high long-term success rates with patellofemoral arthroplasty. The procedure can be considered in patients with primary end-stage osteoarthritis, isolated to the patellofemoral joint. In addition, patients with posttraumatic degenerative arthritis or advanced chondromalacia of either the patellar surface, trochlear surface, or both can also be considered candidates for patellofemoral arthroplasty. Patellofemoral arthroplasty is contraindicated in patients with any evidence of tibiofemoral arthritis or advanced chondromalacia in the medial or lateral compartments.

Patellofemoral arthroplasty is contraindicated in patients with any evidence of tibiofemoral arthritis or advanced chondromalacia in the medial or lateral compartments.Introduction

Osteoarthritis limited to the patellofemoral joint has been a disabling condition for many patients, and a very challenging clinical entity to treat. The incidence of isolated patellofemoral arthritis has continued to increase and will continue to create greater demands for more definitive treatment options.1 Davies and colleagues reported in a radiologic study that isolated patellofemoral arthritis was found in 9.2% of 206 knees in 174 consecutive patients older than 40 years of age.2 Another study by McAlindon and associates found that as many as 24% of women and 11% of men over the age of 55 with symptomatic knee arthritis had isolated degenerative arthritis of the patellofemoral articulation.3 Initial management of patellofemoral arthritis will consist of conservative measures, including appropriate physical therapy to restore patellofemoral mechanics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications combined with injection treatment, weight reduction, and activity modification. When nonsurgical treatment is ineffective and pain becomes disabling, surgical alternatives may be considered.

Nonarthroplasty options for patellofemoral arthrosis have typically provided incomplete relief, with short-term fair to good results in 20–75% of patients. Arthroscopy with débridement and marrow stimulation procedures have had limited short-term results, with only 40–60% of patients with satisfactory results.4 Osteochondral allograft procedures, autologous chondrocyte implantation, with or without tibial tubercle osteotomy, have also had inconsistent success, with unsatisfactory short-term results reported as high as 25–30%.5,6 Although patellectomy has been considered a surgical alternative, it results in significant alteration of the patellofemoral biomechanics and will significantly decrease both the quadriceps force and the extensor moment arm. Experimentally, this has been shown to reduce extension power by 25–60%, which can require an increase in quadriceps force of 15–30% to achieve adequate extension torque.7,8 Extension lag and decreased knee flexion after patellectomy are common and are frequently associated with residual knee pain and instability resulting in a failure rate as high as 45%.9 In addition, tibiofemoral joint reactive forces have been shown to increase as much as 250% after patellectomy, which therefore will increase the risk of progressive degenerative arthritis of the tibiofemoral joint space.10

Patellofemoral arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty continue to remain the most predictable treatment alternatives for isolated degenerative arthritis of the patellofemoral joint. Although total knee arthroplasty is a successful treatment option for some patients, it may not be desirable in all patients.11 Patellofemoral arthroplasty can provide a more conservative approach, and it may be more appropriate in the properly selected patient. In contrast to total knee arthroplasty, patellofemoral arthroplasty will address only the affected area of pathology, with the ability to preserve the tibiofemoral joint space, medial and lateral menisci, and both the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments. More normal knee kinematics and physiologic motion can therefore be preserved with patellofemoral arthroplasty. With the development of new implant designs, and improved surgical technique, more consistent and predictable clinical success can be achieved.

Indications/Contraindications

In the past, success with patellofemoral arthroplasty has been inconsistent and unpredictable. This has largely been related to poor implant design, lack of good surgical instrumentation, and poor patient selection. Appropriate patient selection remains the key factor in achieving high long-term success rates with patellofemoral arthroplasty. The procedure can be considered in patients with primary end-stage osteoarthritis, isolated to the patellofemoral joint. In addition, patients with posttraumatic degenerative arthritis or advanced chondromalacia of either the patellar surface, trochlear surface, or both can also be considered candidates for patellofemoral arthroplasty. Patellar or trochlear dysplasia can also be successfully treated with patellofemoral arthroplasty. Slight tilt or subluxation observed on preoperative tangential radiographs can successfully be treated with patellofemoral arthroplasty. It is extremely important to address any patellar malalignment abnormalities, either preoperatively or intraoperatively. Patellar instability or chronic recurrent patellar dislocation is considered a contraindication to patellofemoral arthroplasty unless the condition has been successfully treated prior to surgery.12 It is important to understand that patellofemoral arthroplasty is a resurfacing procedure and will not correct any preexisting rotational or angular malalignment of the knee. This is a unique difference from total knee arthroplasty in that patellofemoral arthroplasty will not correct or change the mechanical or anatomic axis, as well as femoral or tibial rotation. Preoperative alignment assessment is also critical in determining the likelihood for the future development of degenerative arthritis of the tibiofemoral joint space and/or patellar maltracking, subluxation, and dislocation.

Patellofemoral arthroplasty is contraindicated in patients with any evidence of tibiofemoral arthritis or advanced chondromalacia. This is important to identify preoperatively, as the most common cause for long-term failure, or the need for conversion of patellofemoral arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty, is progressive degenerative arthritis of the tibiofemoral joint space.13 In addition, uncorrected patellar instability combined with severe patellofemoral malalignment will present an increased risk for early failure and usually is best treated with total knee arthroplasty.14 More recent emerging technology has allowed for chondral abnormalities of the medial or lateral femoral condyles to be addressed simultaneously at the time of patellofemoral arthroplasty.15 Clinical experience, however, is limited at this time and such combined procedures should be used only in carefully selected clinical conditions. Patellofemoral arthroplasty is also not appropriate in patients with inflammatory arthritis or chondral calcinosis of the weight-bearing surfaces of the tibiofemoral joint space or menisci. Patients with chronic anterior knee pain that cannot be directly attributed to the patellofemoral joint space are also poor candidates for this procedure. It is also very important that the patient has realistic expectations regarding the extent of pain relief, the duration of recovery, and the allowable postoperative activities following patellofemoral arthroplasty in order to achieve high success rates.

Patellofemoral arthroplasty has been found to be most suitable for the younger or middle-aged patient (55–60 years), providing a more definitive resolution without the need for performing a total knee arthroplasty.16 Typically, the younger patients have been told to live with their severe disability because they were “too young” for total knee arthroplasty as the only option. It is difficult to recommend the sacrifice of both the medial and lateral compartments, as well as the anterior cruciate ligament and the posterior cruciate ligament, to treat the arthritic patellofemoral compartment if an equally successful and less destructive alternative can be found. Patellofemoral arthroplasty can therefore offer a reasonable treatment option for patients with severe disabling degenerative arthritis isolated to the patellofemoral joint, yet who are too young for total knee arthroplasty, as well as being a less destructive option for the older patient. In the appropriately selected patient, long-term survivorship has been reported as high as 98% with an average follow-up of 17 years.17 It can also be utilized as an interim step when total knee arthroplasty may not be the ideal treatment option due to age or other clinical circumstances.16 Conversion of patellofemoral arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty has been shown by several authors to be equally successful as primary total knee arthroplasty without the need for bone grafting, special augments, or a varus-valgus constrained revision knee implant.17 Older patients (60–85 years) are also good candidates, as this can provide a more conservative and less invasive approach than total knee arthroplasty.12,18

Clinical Evaluation and Preoperative Planning

A full preoperative evaluation should be undertaken, including a very detailed history and physical examination to verify that the symptoms and clinical findings are isolated to the patellofemoral joint. The history should focus on any elements of prior patellar instability with previous history of recurrent subluxation and/or dislocation. It is extremely important that the symptomatology be localized to the anterior compartment of the knee, and that it originates from the degenerative process of the chondral surfaces of the patellofemoral joint, and is not related to the peripatellar soft tissue structures. Many times these patients will have had prior surgical procedures, with arthroscopy being the most common surgical intervention performed. This sometimes may include lateral release, chondroplasty, and prior realignment procedures. Pain should be primarily isolated to the patellofemoral joint and will frequently be associated with retropatellar crepitus. Patellofemoral pain is often exacerbated by activities such as stair climbing, rising from a chair, sitting with the knee flexed, squatting, and walking on uneven ground. Leslie and Bentley have found that the clinical triad of quadriceps wasting greater than 2 cm, chronic effusion, and retropatellar crepitance are the best physical predictors of articular cartilage breakdown of the patellofemoral joint.19

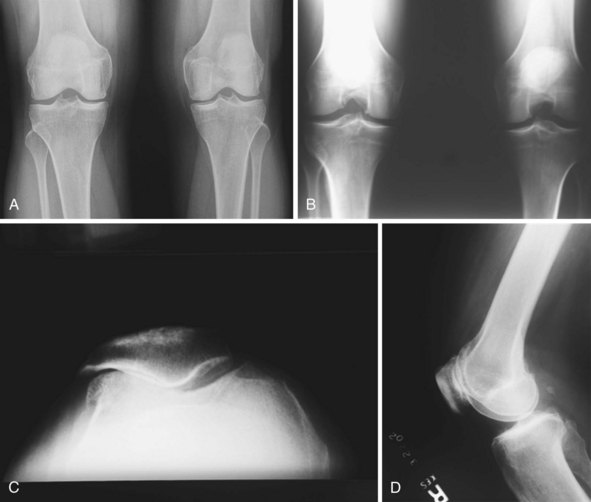

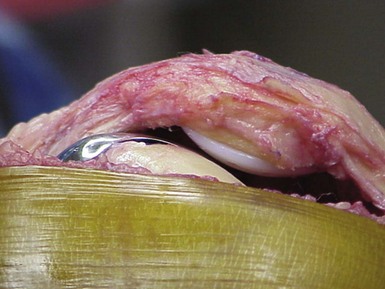

Standing weight-bearing radiographs are essential for evaluation of the femorotibial joint space; these should include a standing bilateral anteroposterior view, a 45° flexion posteroanterior view, and lateral and skyline views20 (Fig. 20–1). A long-leg standing weight-bearing (1.37 cm) axial alignment radiograph is also necessary to further evaluate the anatomic and mechanical axis of the knee (Fig. 20–2). Mild changes of the tibiofemoral joint space may be accepted; however, if there are any concerns for early degeneration of the chondral surface of the medial or lateral compartments, or associated meniscal pathology, then further evaluation is required either arthroscopically or at the time of surgery. Lateral radiographs are helpful in demonstrating degenerative changes of the patellofemoral joint but more useful for the assessment of patella alta or patella baja. Tangential radiographic views or skyline views are helpful in confirming the presence of severe degenerative change of the patellofemoral joint, but sometimes may not accurately identify the severity of the degeneration. It is not uncommon to observe some apparent joint space preservation with minimal or no osteophytes in the presence of severe articular cartilage loss (Fig. 20–3).

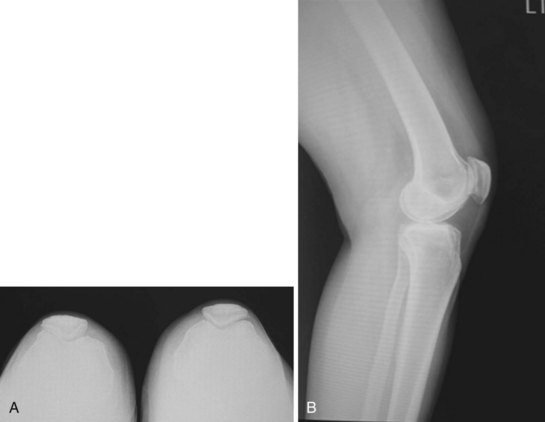

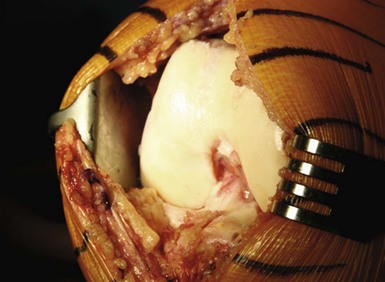

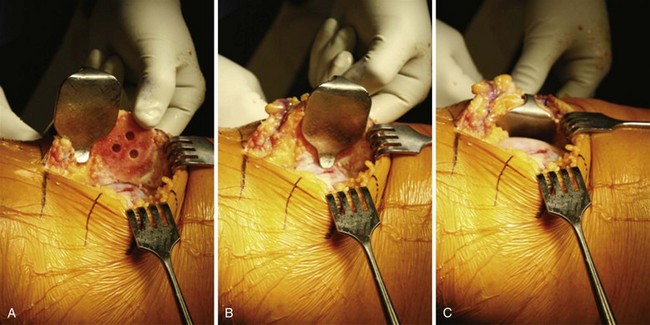

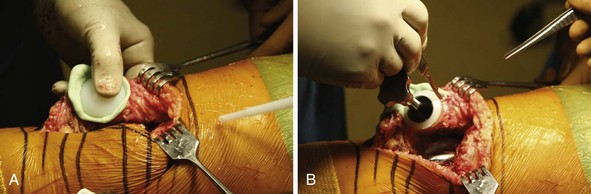

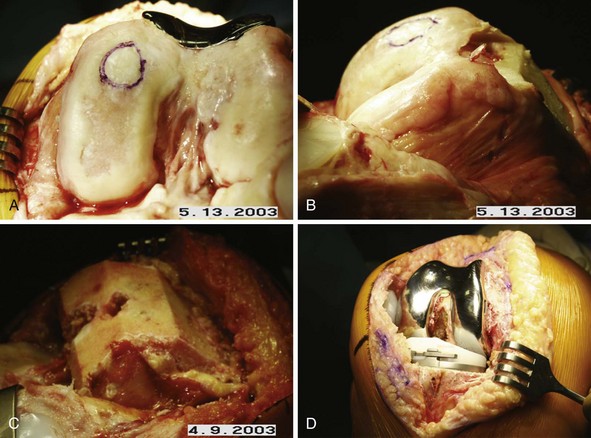

Arthroscopic evaluation has been helpful in this setting when there are questions as to the severity and degree of cartilage degeneration, as well as any other concerns for intra-articular pathology (Fig. 20–4). The clinical success of arthroscopy for isolated osteoarthritis of the patellofemoral joint has been unpredictable, but it can have value in evaluating the severity of the chondral change if this is not clearly defined on the preoperative radiographic evaluation, or there is uncertainty for the indication to perform a patellofemoral arthroplasty. Other areas of concern, such as early degeneration of the tibiofemoral joint space and meniscal pathology, may also be evaluated at the time of arthroscopic evaluation. This evaluation is extremely critical, as this will certainly play into the future prognosis and long-term success of patellofemoral arthroplasty. Photographs from prior arthroscopic treatment can also be of extreme value in a thorough evaluation of the knee to validate whether the degenerative process is isolated to the patellofemoral joint.

Figure 20–4 (A) Arthroscopic view of the patellofemoral joint of the patient in Figure 20–3 revealing severe grade IV degenerative changes on both the patellar and trochlear surfaces. (B) Arthroscopic view of the medial compartment of the same patient revealing intact articular surfaces and a normal medial meniscus. (C) Arthroscopic view of the lateral compartment showing a normal lateral meniscus and normal articular cartilage.

Surgical Technique

Setup and Equipment

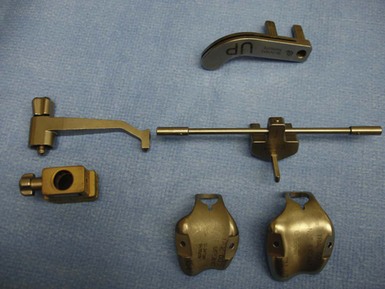

The procedure is approached in a manner similar to that of total knee arthroplasty, utilizing general or regional anesthesia. A short-acting spinal anesthetic with light sedation is preferable, as this will allow for a more successful approach with pain management. This has also been very beneficial in initiating early weight bearing and recovery of quadriceps muscle function within hours after the procedure. After induction of anesthesia, the patient is positioned in the supine position, with a small bolster placed at the foot of the bed to allow for knee flexion between 70° and 90° (Fig. 20–5). Hyperflexion is not necessary and can sometimes hinder the exposure of the distal femur. The surgical instrumentation is relatively simple and follows the same principles as total knee arthroplasty (Fig. 20–6). Intramedullary instrumentation is used for the anterior femoral resection, followed by preparation of the trochlea with a simple motorized rasp.

Technical Description

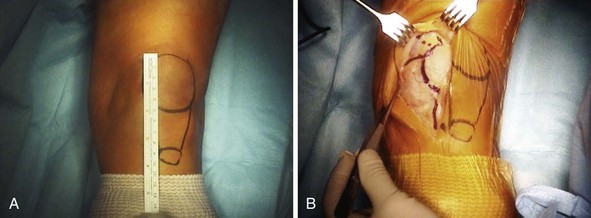

The surgical exposure for patellofemoral arthroplasty is slightly different than that used in total knee arthroplasty. Care must be taken to evaluate, observe, and protect the normal anatomy throughout the procedure. The skin incision is made just medial to the midline in order to minimize problems with point-loading during kneeling20 (Fig. 20–7). The incision should extend from approximately 1–2 cm above the superior pole of the patella to just 1 cm below the joint line. It is not necessary to extend the incision distally as much as would be performed in a total knee arthroplasty as most of the exposure will focus on the anterior and distal femur. The joint capsule and synovium can be opened using a standard short medial patellar arthrotomy or a midvastus approach (Fig. 20–8). A small mini-arthrotomy is ideal, as this will facilitate exposure for referencing the anterior cortex during the procedure. Care is taken to minimize resection of the fat pad and be cautious of the anterior horn of the lateral and medial menisci, as well as the intermeniscal ligament.

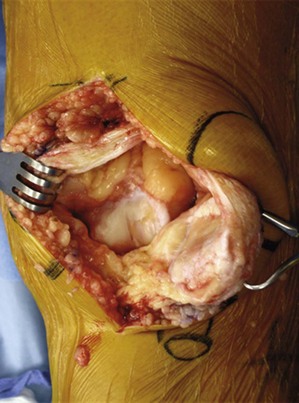

Prior to proceeding with the patellofemoral arthroplasty, it is important to perform a thorough inspection of the entire joint to make certain there are still appropriate indications for the procedure (Fig. 20–9). A thorough discussion prior to surgery is essential in order to prepare the patient that, if significant degenerative changes are noted in the medial or lateral weight-bearing areas or any other significant pathology is identified, a total knee arthroplasty can be performed simultaneously. If a femoral condylar defect is noted in addition to isolated patellofemoral arthritis, then an osteochondral plug can be harvested from the relatively healthy area of the trochlea or from the intercondylar notch (Fig. 20–10). It is important to assess the size of the condylar defect, as there is still limited clinical experience with this combined approach, keeping in mind that progressive degeneration of the femorotibial joint space can be the cause of short-term failure.

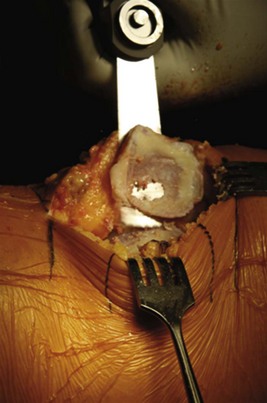

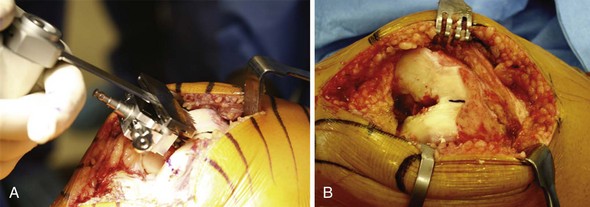

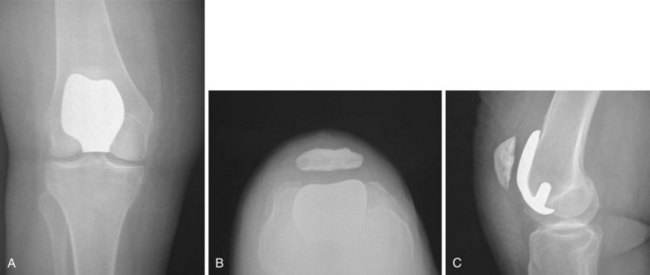

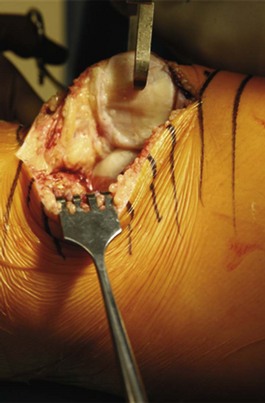

With the leg in full extension, resection of the patella can be performed first in order to facilitate the exposure of the distal femur for preparation of the trochlea. This will also avoid eversion of the patella, which will minimize the soft tissue trauma to the extensor mechanism. Patellar resection is performed using the same principles followed in total knee arthroplasty, with a measured resection approach. Using a towel clip, the patella can be easily everted and stabilized for preparation (Fig. 20–11). Removing the surrounding synovial tissue from the periphery of the patella is helpful in accurately identifying the level of resection. If necessary, the infrapatellar fat pad can be partially excised to also facilitate exposure. Once the periphery of the patella is cleared of synovial tissue to define its margins, a measured resection can be performed. As in total knee arthroplasty, it is extremely important to restore the native patellar thickness to avoid overstuffing the patellofemoral joint, which can affect patellar articulation, patellar tracking, and range of motion. The patella should be measured using calipers in all four quadrants in order to retain the normal patellar height in the most accurate manner, and to avoid an oblique level of resection (Fig. 20–12). Transverse patellar osteotomy can be performed utilizing a freehand method or instrument method, depending on the surgeon’s preference (Fig. 20–13). The resection level should be parallel, and once again, assessment should be made with the caliper in all four quadrants to avoid the risk of an oblique cut, which could contribute to patellar mal-tracking (Fig. 20–14). Sizing of the patella can then be performed in the usual manner, taking care to medialize the patella to enhance patellar tracking (Fig. 20–15). If there is a portion of the lateral patellar facet not covered by the patellar component, removal of this bone should be performed in order to avoid any potential source of impingement, which may occur during articulation (Fig. 20–16). The thickness of the patella should then be reassessed following insertion of the prosthetic component trial. Ideally the goal is to have the thickness of the remaining patella and the patellar prosthesis equal to the appropriate patellar thickness.

Figure 20–12 Patellar thickness is measured with the caliper, with assessment of both the medial and lateral facets.

Figure 20–16 Excess bone from the lateral facet is removed to avoid a potential source of bone impingement.

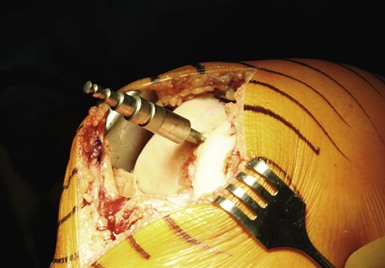

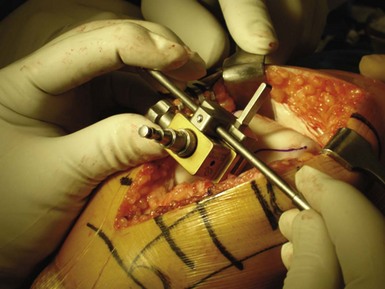

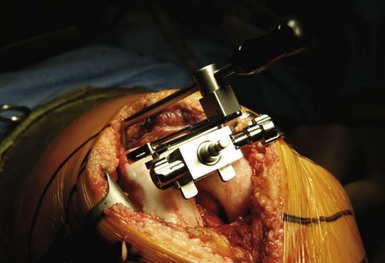

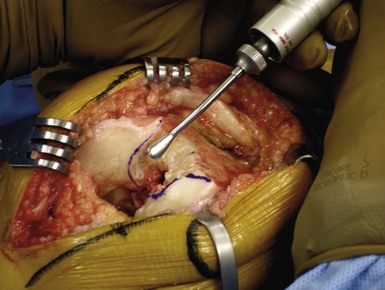

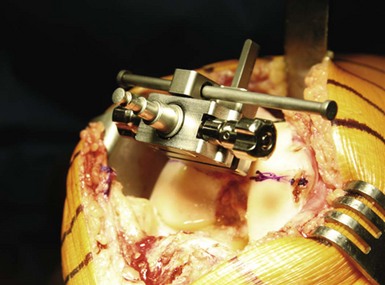

Once the patella has been appropriately prepared, it can be easily displaced into the lateral gutter, thereby avoiding eversion of the patella with much less surgical trauma or injury to the quadriceps extensor mechanism. A custom-designed patellar retractor has been developed to facilitate the retraction of the patella, as well as protect the resected surface throughout the procedure (Fig. 20–17). The knee is then flexed and held in a position between 70° and 90° of flexion. It is important to note that hyperflexion should be avoided as this can cause greater difficulties with exposure of the distal femur due to the increased tension that is applied across the extensor mechanism the further the knee is flexed. A drill hole is made into the center of the intercondylar notch, in the trochlear groove, approximately 1–2 cm anterior to the roof of the intercondylar notch (Fig. 20–18). Marrow elements are suctioned in order to minimize the risk of fat embolization when the fluted intramedullary rod is inserted for placement of the anterior cutting guide. The intramedullary rod is inserted and securely anchored to the distal femur (Fig. 20–19). The patellofemoral alignment guide block is then inserted over the intramedullary rod with the arrow of the guide block pointing toward the knee. The rotational alignment for the anterior resection can be achieved using Whiteside’s line, as exposure of the medial and lateral epicondyles can sometimes be difficult (Fig. 20–20). If adequate exposure has been obtained, the transepicondylar axis can also be used, positioning the handles of the alignment rod parallel to the epicondylar axis (Fig. 20–21). It is important to note that there should be no additional external rotation added to the alignment of the anterior resection, keeping in mind that this is a resurfacing procedure, which is not designed to correct rotational or angular alignment. The alignment guide block is then secured in place to the intramedullary rod using the small fixation knob. Femoral rotation has now been set, and the patellofemoral alignment rod can be removed. The anterior resection guide is then inserted with appropriate referencing of the anterior cortex in order to provide a minimal amount of bone resection (Fig. 20–22). An angel wing can also be used as a secondary reference to help ensure that the implant will sit flush once the anterior resection has been made without risk for notching. The anterior cut is then made through the slot in the resecting guide using an oscillating saw in the usual manner (Fig. 20–23).

Figure 20–21 Rotational alignment is set parallel to the transepicondylar axis using the alignment rod.

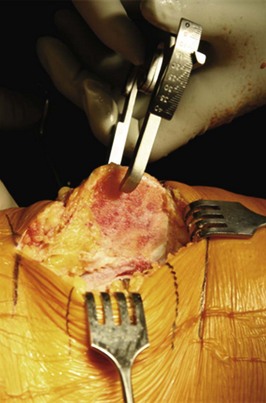

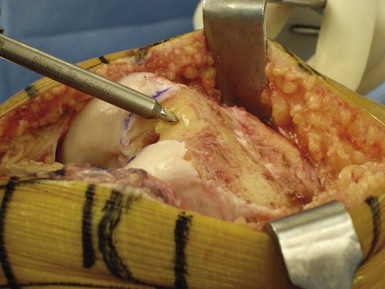

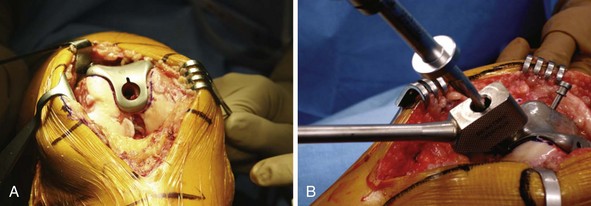

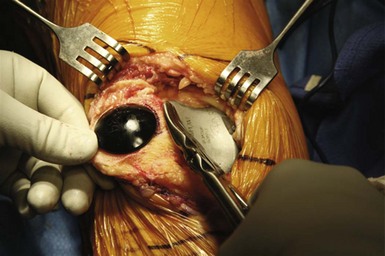

Once the anterior resection has been made, correct femoral component sizing can then be performed utilizing the trial templates (Fig. 20–24). It is extremely important to achieve maximum coverage of the anterior femur. The largest femoral component should therefore be used in order to create complete coverage of the anterior femur without medial or lateral overhang. Once the appropriate size has been chosen, the intercondylar notch portion of the trial component can be outlined with methylene blue to correctly identify the cartilage to be resected (Fig. 20–25). Using a conical or a motorized rasp, the articular cartilage can be removed in the designated area of the trochlear groove to accommodate the implant (Fig. 20–26). It is important to note that only minimal rasping is required, so as not to inset the intercondylar portion of the implant to the bone. The implant is designed as an onlay prosthesis, and therefore will fit 1–2 mm proud of the intercondylar bone surface. This is a critical point, as this prosthesis will allow the patellar component to articulate with the femoral component without contacting the articular cartilage during flexion. This has been one of the concerns with long-term success, as early articular erosion has been identified with other implant designs. Multiple cement fixation drill holes are made to assure appropriate cement penetration for component fixation (Fig. 20–27). Using the trial template, the drill hole is then created to accommodate the central peg of the prosthetic component (Fig. 20–28). Trial reduction can then be performed to make certain that restoration of normal patellofemoral mechanics and alignment has been achieved (Fig. 20–29). There should be no evidence of patellar tilt or subluxation throughout the full range of motion with the usual “no-touch technique” as utilized in total knee arthroplasty. If any increase in patellar tilt or mild subluxation is identified, this can be addressed successfully by performing a lateral release. With appropriate patient selection and surgical technique, proximal realignment at the time of surgery should be unnecessary in most cases and ideally identified preoperatively.

Preparation of the anterior femoral surface as well as the patellar surface can then be made in the usual manner before application of bone cement and implantation of the patellofemoral component. Cement is applied to both the trochlear component and the prepared surface of the femur to assure adequate cement penetration (Fig. 20–30). Manual pressure is applied to the trochlear component, while a patellar clamp is used for the patellar component until the cement cures (Fig. 20–31). Meticulous attention to detail is important in order to remove all excreted cement and avoid any possibility of third body wear. Final assessment for patellar alignment and tracking can then be made, followed by thorough lavage of the wound and standard closure of the arthrotomy, as well as the subcutaneous layer and a subcuticular closure of the skin (Fig. 20–32). The unique design of this component with a central peg eliminates any concerns for the transitional area into the notch that can sometimes cause impingement or interfere with tracking of the patella in deep flexion (Fig. 20–33). Postoperative radiographs are performed in order to confirm appropriate implant position and alignment (Fig. 20–34).

Postsurgical Follow-Up

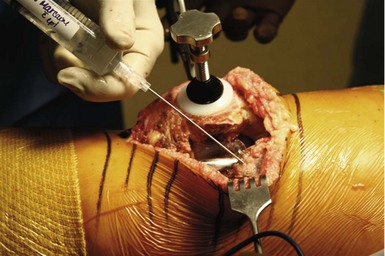

Because most patients with patellofemoral arthritis will have preexisting quadriceps insufficiency, it is extremely important to begin the development of the quadriceps muscle preoperatively. Appropriate pain management is essential in the early postoperative phase in order to restore quadriceps function and to prevent shutdown of the extensor mechanism. Intra-articular injection performed at the time of surgery with a “pain cocktail” has been helpful in minimizing pain in the early postoperative phase21 (Fig. 20–35). Quadriceps isometric exercises, straight leg raises, and range-of-motion exercises are started immediately on the day of surgery. The use of a continuous passive motion machine is helpful during the hospitalization, but may not be necessary for all patients. Full weight bearing is permitted immediately, and patients are encouraged to begin weight bearing on the day of surgery with the use of crutches, walker, or a cane. Ketorolac (Toradol) 15 mg intravenously has been extremely helpful in controlling the inflammatory response when given preoperatively, in addition to every 6 hours for the first 24 hours postoperatively, in patients without allergy to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories. Thromboembolism prophylaxis is used similar to that for total knee arthroplasty, with warfarin (Coumadin) being utilized during the hospital stay. The majority of patients will continue with enteric-coated aspirin (325 mg twice daily) for 4–6 weeks, unless there is an increased risk for thromboembolism or increased bleeding tendency where aspirin cannot be utilized. In these situations, warfarin is used for 2 weeks. Intravenous antibiotics are used for the first 24 hours in order to prevent infection. When quadriceps strength returns, patients are allowed to progress with unrestricted activities, with recommendation to avoid excessive loading and deep flexion, and high-impact activities.

Clinical Results

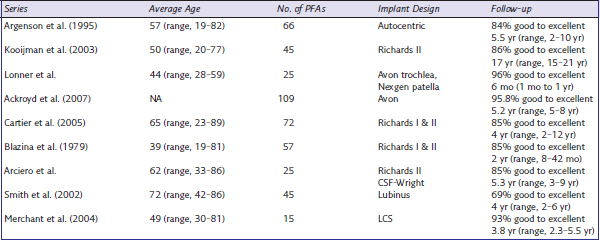

Inconsistent results for patellofemoral arthroplasty have been largely related to poor component design, lack of instrumentation, and poor patient selection. Many techniques relied on a freehand method of bone preparation, creating greater variability in component placement and depth of bony resection. New design concepts have been implemented to allow for a more accurate method of bone preparation with an instrumented technique and improved patient selection. Most studies have reported good to excellent results in approximately 80–90% of cases at short- and midterm follow-up (Table 20–1). McKeever, in 1955, was the first to describe good results following patellar resurfacing using a metal prosthesis fixed with a screw.22 Subsequently, other authors reported varied results using this technique. Blazina et al., in 1979, were the first to describe resurfacing of both the patella and trochlear surface.23 Various publications over the years, however, have had success rates varying from 44% to 90%. Kooijman et al.24 reported excellent or good results in 86% of cases with a mean follow-up of 17 years. In the patient group without ongoing tibiofemoral arthritis, the survivorship increased to 98%. In 1988, Arciero et al.25 reported on 20 patellofemoral arthroplasties with 85% satisfactory results, and in 2006 Ackroyd et al. reported a 95.8% survivorship at 5 years’ follow-up with no cases of failure of the prosthesis.26 Poor component design and inconsistent patient selection criteria have also contributed to early failures of patellofemoral arthroplasty. Original descriptions of the procedure did not include strict inclusion criteria for patient selection, and had numerous technical pitfalls with little emphasis based on realignment of the extensor mechanism of the knee. Consequently, early designs showed disappointing results. Over the years, with the development of new implant designs, improved surgical instrumentation, and more accurate patient selection criteria, the clinical success of patellofemoral arthroplasty has improved significantly.18

When compared to total knee arthroplasty, patellofemoral arthroplasty has the potential advantage of retaining the menisci and the cruciate ligaments, and thereby retaining more natural kinematics of the knee joint with a less invasive procedure. The main reasons for early failure have been persistent malalignment, wear, impingement, and progressive degeneration of the tibiofemoral joint space. In the past 5 years, newer implant designs have been introduced that can more accurately reproduce patellofemoral joint function. Ackroyd et al. reported on 306 patellofemoral arthroplasties in 240 patients with a high level of pain relief and improved function. In 5 years of follow-up, there was no significant deterioration in function or progression of pain, and there were no late complications attributed to the arthroplasty.26 Disease progression in the tibiofemoral joint space occurred in 14 patients (16 knees, 5%) requiring conversion in 10 of these patients (11 knees, 3.6%), and anterior knee pain was recorded in 14 knees (4%). There were no failures secondary to mechanical loosening. In 2006, Sisto and Sarin reported on 25 custom patellofemoral arthroplasties, with intention to recreate the patient’s own anatomy and to address any inherent problems associated with designed implants.27 Computed tomography scanning was utilized to construct a three-dimensional model of the patient’s femoral groove, which then allowed for the creation of a cobalt chrome custom implant. Subsequent follow-up was 73 months (6 years), and all 25 implants were in place and functioning well. The Knee Society Functional Score was 89 points, and the Knee Society objective score was 91 points, with 18 excellent and 7 good results. No patient had required additional surgery or had component loosening.

Patellofemoral arthroplasty can produce consistently good-quality functional results in the appropriately selected patient with the major advantage of preservation of the tibiofemoral joint, as well as the medial and lateral menisci and cruciate ligaments. Early results with new prosthetic designs have been encouraging, with the ability to restore considerable improvement in function and range of motion, as well as significant decrease in pain. Patient selection for patellofemoral arthroplasty remains one of the key factors in achieving high success rates. Lonner, in 2004, showed that the results of patellofemoral arthroplasty can be optimized by accurate alignment and positioning of the prosthesis combined with appropriate balance of the soft tissue structures to enhance more normal patellar tracking. He noted that implant design may also play a factor in patellofemoral complications.18 It is also important to note that the incidence of patellar complications was found to be reduced from 17% with a first-generation implant to 4% with a second-generation implant.

Complications

Early failure for patellofemoral arthroplasty has been primarily related to persistent pain secondary to patellar snapping and instability. Further surgical intervention sometimes is necessary, which may involve an arthroscopic approach or possibly revision surgery to improve soft tissue alignment and/or to revise the trochlear prosthesis. Many of these problems have been related to implant design features, as well as extensor mechanism malalignment that was not accurately identified preoperatively. There has been a substantial improvement in contemporary design that has reduced the tendency for patellar maltracking or dysfunction due to the improvement in the prosthetic trochlear geometry. Soft tissue impingement resulting in residual anterior knee pain and/or patellar instability may occur in a small percentage of patients, and is similar in frequency to that seen in total knee arthroplasty. The long-term concerns of component subsidence, loosening, and polyethylene wear have been extremely uncommon, occurring in less than 1% of published cases combined. Component loosening of the trochlea has been more common in the cementless design. Progressive degenerative arthritis of the tibiofemoral joint space has been the most common cause for failure of patellofemoral arthroplasty, occurring in approximately 20% of knees at 15 years’ follow-up. If revision to total knee arthroplasty is necessary, the procedure can be performed in a similar fashion as a standard primary total knee arthroplasty (Fig. 20–36). The all-polyethylene patellar component can usually be retained, and a standard total knee arthroplasty can be performed without the need for stems, augments, bone grafting, and use of a varus-valgus constrained component. The clinical outcomes following conversion to total knee arthroplasty have been encouraging, with clinical results comparable to those for primary total knee arthroplasty.17

Tips and Pearls

1 Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, et al. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2007;89:780-785.

2 Davies AP, Vince AS, Shepstone L, et al. The radiologic prevalence of patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;402:206-212.

3 McAlindon RE, Snow S, Cooper C, et al. Radiographic patterns of osteoarthritis of the knee joint in the community: the importance of the patellofemoral joint. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:844-849.

4 Federico DJ, Reider B. Results of isolated patellar debridement for patellofemoral pain in patients with normal patellar alignment. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:663-669.

5 Fulkerson JP. Anteromedialization of the tibial tubercle for patellofemoral malalignment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;177:176-181.

6 Minas T, Chiu R. Autologous chondrocyte implantation. Am J Knee Surg. 2000;13:41-50.

7 Ackroyd CE, Polyzoides AJ. Patellectomy for osteoarthritis: a study of 81 patients followed from two to twenty-one years. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1978;60:353-357.

8 Kaufer H. Mechanical function of the patella. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1971;53:1151-1156.

9 Laskin RS, Palletta G. Total knee replacement in the patient who had undergone patellectomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1995;77:1708-1712.

10 Dinham JM, French PR. Results of patellectomy for osteoarthritis. Postgrad Med. 1972;48:590.

11 Laskin RS, Van Steijn M. Total knee replacement for patients with patellofemoral arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;367:89-95.

12 Grelsarner RP. Current concepts review: patellofemoral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2006;188:1849-1859.

13 Lonner JH. Patellofemoral arthroplasty. In: Lotke JL, Lonner JH, editors. Knee Arthroplasty. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:343-359.

14 Mont MA, Haas S, Mullick T, et al. Total knee arthroplasty for patellofemoral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2002;84:1977-1981.

15 Lonner JH, Mehta S, Booth RE. Ipsilateral patellofemoral arthroplasty and autogenous osteochondral femoral condylar transplantation. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:1103-1136.

16 Gioe TJ, Novak C, Sinner P, et al. Knee arthroplasty in the young patient: survival in a community registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:83.

17 Lonner JH, Jasko JG, Booth RE. Revision of a failed patellofemoral arthroplasty to a total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2006;88:2337-2342.

18 Lonner JH. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: the impact of design on outcomes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39:347-354.

19 Leslie IJ, Bentley G. Arthroscopy in the diagnosis of chondromalacia patellae. Ann Rheum Dis. 1978;37:540-547.

20 Yacoubian SV, Scott RD. Skin incision translation in total knee arthroplasty: the difference between flexion and extension. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:353-355.

21 Busch CA, Shore BJ, Bhandari R, et al. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2006;88:949-963.

22 McKeever DC. Patellar prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1955;37:1074.

23 Blazina M, Fox JM, Deo Pizzo W, et al. Patellofemoral replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;144:98-102.

24 Kooijman HJ, Driessen APPM, van Horn JR. Long-term results of patellofemoral arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2003;85:836-840.

25 Arciero R, Toomey H. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: a three to nine year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;236:60.

26 Ackroyd CE, Newman JF, Elderidge J, Webb M. The Avon patellofemoral arthroplasty: two to five year results. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2003;85(Suppl 11):162-163.

27 Sisto DJ, Sarin VK. Custom patellofemoral arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2006;88:1475-1480.

Carrier P, Sanouiller JL, Grelsamer R. Patellofemoral arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5:49.

Fulkerson JP. Disorders of the Patellofemoral Joint. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996.

Harrington KD. Long term results for the McKeever patellar resurfacing prosthesis used as a salvage procedure for severe chondromalacia patella. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;279:201-213.

Hendrix MRG, Ackroyd CE, Lonner JH. Revision patellofemoral arthroplasty: 3-7 year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:977-983.

Jackson RW, Kunkel SS, Taylor GJ. Lateral retinacular release for patellofemoral pain in the older patient. Arthroscopy. 1991;7:283-286.

Krajca-Radcliffe JB, Coker TP. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: a 2 to 18 year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;330:143.

Levitt RL. A long term evaluation of patellar prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;97:153-157.

Merchant AC. Early results with a total patellofemoral joint replacement arthroplasty prosthesis. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:829-836.

Rosenberg TD, Paulos LE, Parker RD, et al. The forty-five degree posteroanterior flexion weight-bearing radiograph of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1988;70:1479-1483.

Sisto DJ. Patellofemoral degenerative joint desease. In: Fu FH, Harner DC, Vince K, editors. Knee Surgery. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994:1203-1221.

Tauro B, Ackroyd CE, Newman JH, et al. The Lubinus patellofemoral arthroplasty: a five to ten year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2001;83:696.