Patella Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

Daniel A. Farwell and Craig Zeman

Patella fractures can occur in a wide variety of individuals. Both genders have similar fracture rates. Age-related incidence of patella fractures tends to be shifted to a mature population. Patella fractures are usually caused by direct trauma or a blow to the patella,1–4 or can be a postoperative complication from ACL or total knee replacement surgery.5–8 Depending on the force of the injury, the fracture can be nondisplaced or highly comminuted with significant injury to the extensor mechanism complex. Active extension of the knee is usually preserved with a nondisplaced fracture. However, in a displaced fracture the extensor mechanism is disrupted to the extent that active extension is not possible. Displaced fractures require open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) to maximize active extension of the knee and decrease the incidence of posttraumatic arthritis.

Surgical Indications and Considerations

Physicians use two main criteria to determine whether surgery is indicated:

Different surgical treatments are based on the type or severity of the fracture. Tension band wiring is still the most accepted treatment for displaced patella fractures.9–11 Weber and colleagues12 noted that if stability and early range of motion (ROM) is to be performed, there must be a stable repair of the fracture site to avoid displacement of the repair. They noted increased stability by repairing cadaveric patella fractures with a technique in which the wire is anchored directly in bone. They also noted that the retinaculum should be repaired because it added to stability. Bostman and colleagues13 examined several different approaches and techniques to repair patella fractures and discovered the tension band wiring procedure to be far superior to other methods, but using screws with tension band technique appears the strongest.14–16 With the production of Kevlar sutures, the use of sutures to fix patella fractures has been reported.17–19

Smith and associates20 performed a retrospective review of postoperative complications after ORIF of patella fractures. They followed 51 patients treated with the tension band fixation technique until complete healing had occurred at a minimum of 4 months. The authors’ objective was to focus on acute, short-term complications after ORIF of patella fracture. Although the study did not specifically assess clinical parameters, such as pain or strength, it did point out two important factors to consider during rehabilitation. Approximately 22% of the patella fractures treated with modified tension band wiring and early ROM displaced significantly during the early postoperative period.

![]() Failure of fixation was related to unprotected ambulation and noncompliance. Patient noncompliance in restricting early ROM and weight bearing can cause failure of even technically correct tension band wire fixation.3,13,21–23

Failure of fixation was related to unprotected ambulation and noncompliance. Patient noncompliance in restricting early ROM and weight bearing can cause failure of even technically correct tension band wire fixation.3,13,21–23

Joint congruity must be restored to decrease the development of arthritis, and the extensor mechanism must be restored to regain full extension. Most patients with displaced fractures are candidates for ORIF. If the patient was ambulatory before the injury and can medically tolerate surgery, then surgery should be performed regardless of age. Situations in which nonambulatory patients with patella fractures lack lower-extremity (LE) function and sensation (neurologic impairment) can be managed conservatively.

Patients with simple two-part fractures have a better chance of a successful outcome than those with highly comminuted fractures. The variability of outcomes relates to the degree of fixation and the ability of the fracture site or sites to consolidate. In some cases of irreducible comminution, the fragments may have to be removed, resulting in a partial or total patellectomy.4,21,24–32 Patellectomy procedures have a lower success rate than stable internal fixation procedures.33–36

Surgical Procedure

Most methods of ORIF incorporate tension band wiring techniques.12,21,22,37,38 Makino and associates described an arthroscopically assisted technique.39 The tension band wire is placed around the proximal and distal pole of the patella through the quadriceps and patella tendons. This wire compresses the fracture site. The surgeon maintains rotational control with one or two screws placed across the fracture site from the proximal to the distal pole. The tension band wire is passed under the k-wires or screws to add compressive and rotational stability to the fixation. Another method is to use cannulated screws through which the tension band wire may be passed. Suture can be used instead of wire in certain cases.17–19

The integrity of the skin over the patella must be evaluated before surgery because of its potential to produce postoperative complications. The therapist should assess this area continually for infection and poor healing because vascular supply may have been disrupted during the trauma that caused the patella fracture.

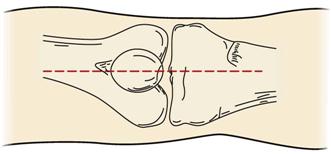

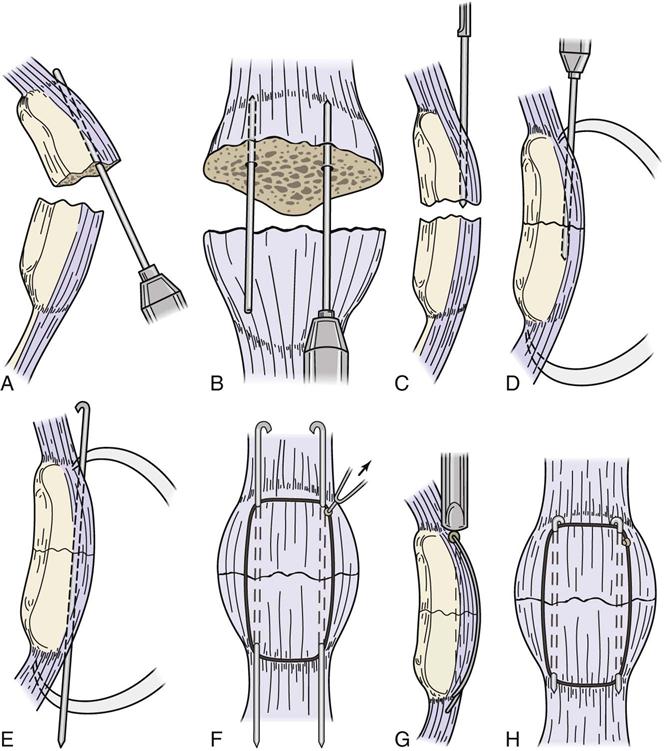

Surgery is performed under either general or regional anesthesia. The patient is positioned supine, and a tourniquet is applied to the thigh. It is important that the knee can fully flex and extend so that the surgeon can determine the stable postoperative ROM. The leg is then prepped and draped in sterile fashion. If the skin allows, then a longitudinal midline incision is made over the patella. This incision (Fig. 26-1) is carried down to the peritenon, and full-thickness flaps are developed both medially and laterally to expose the entire patella and extensor mechanism. The peritenon is then incised to expose the fracture and the tendons. The fracture hematoma is débrided from the fracture site, and the raw cancellous bone is delineated to aid in fracture reduction. Two k-wires are then run from the fracture site of the proximal fragment and out the proximal pole of the patella (Fig. 26-2, A to C). The proximal and distal fragments of the patella are brought together to reduce the fracture. The fracture is then held together with bone-holding forceps while the knee is in extension (Fig. 26-2, D). The k-wires are passed back through the middle of the patella and out the distal pole. The bone-holding forceps are then removed (Fig. 26-2, E). Next the tension band wire is placed around the patella and k-wires. It should be positioned as close to the bone and k-wires as possible to minimize complications after ROM is initiated postoperatively (Fig. 26-2, F).

To place the tension wire as close to the bone and k-wire as possible, the surgeon usually passes a hollow needle under the k-wire and over the bone to guide the tension band wire. The tension band wire is then passed through the needle and brought around the patella. The two ends of the tension band wire are then twisted together with pliers to add tension to the system. The surgeon must be careful not to add too much tension to the wire because this may cause the wire to break early in the rehabilitation process (Fig. 26-2, G and H).

The surgeon then repairs the extensor mechanism. The medial and lateral retinacula are commonly torn in line with the fracture. These tears are simply repaired using nonabsorbable sutures. After this last repair, the surgeon checks the ROM to ensure that the patient can easily obtain full extension and at least 90° of flexion. The surgical site is then closed in the following order: first the peritenon, then the subcutaneous tissue, and finally the skin. The wound is dressed with a bulky dressing and placed in an immobilizer. A postoperative water-cooling system or ice pack may be used to assist with pain control immediately.

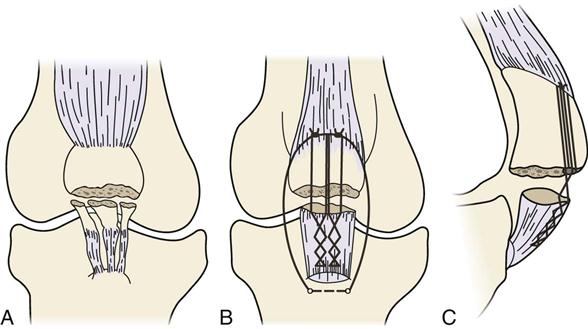

A partial patellectomy may be performed in patients with comminuted displaced fractures who have at least 50% of the patella remaining.33 The inferior pole of the patella usually suffers the most trauma, resulting in its removal (Fig. 26-3, A). To do a partial patellectomy, the surgeon débrides the bone fragments from the tendon end and then weaves two large 5-0 nonabsorbable sutures into the tendon (5-0 FiberWire is now available that has the strength of 18-gauge wire and the flexibility of suture). The surgeon then drills two holes longitudinally into the remaining piece of the patella. The sutures in the tendon are brought through the holes in the patella and tied over the bone bridge formed by the two holes (Fig. 26-3, B and C).

Most patients require a second operation to remove the hardware placed in the patella.40 The wires and sutures can become prominent and bother the patient during rehabilitation, slowing progress in gaining ROM.

The fixation of simple fractures is usually the most stable immediately after surgery. If the tension band wire is not placed right next to the screw, then the wire can cut through the tendon until it butts up against the screw, decreasing the compressive effect of the wire and possibly allowing the fracture to displace. Stable fixation of a simple fracture is usually strong enough to allow early passive range of motion (PROM). The amount of ROM is dictated by the surgical procedure and pain tolerance. Time frames to initiate physical therapy vary depending on the degree of comminution. The repair is most vulnerable between 4 to 6 weeks when the bone and tendon have not completely healed and the pins and wires have loosened. After 8 weeks, the repair should be stable enough to allow aggressive therapy with the goal of regaining full ROM.41

![]() The exception to this time frame is the patient who has a comminuted fracture with unstable fixation. This type of situation may require 12 weeks before the initiation of therapy. Most patients return to preinjury activities (sports) by 6 months after surgery.

The exception to this time frame is the patient who has a comminuted fracture with unstable fixation. This type of situation may require 12 weeks before the initiation of therapy. Most patients return to preinjury activities (sports) by 6 months after surgery.

Outcomes

A successful outcome is a knee with full active extension, full ROM, and without significant pain. The things that can prevent a successful outcome are unstable fixation, incongruous reduction, poor patient compliance, and delays in early PROM exercises. Unstable fixation will decrease the aggression of the rehabilitation program. A poorly reduced joint will make ROM exercises more painful and limit the speed at which the patient will tolerate increases in ROM and strengthening exercises. This procedure is painful. Patients with poor pain tolerance will not regain strength and ROM as easily as patients who are motivated and who can handle an aggressive rehabilitation program. Some early postoperative ROM exercises need to be started to get the best results. If ROM exercises are delayed in the first few weeks for any reason, then it will be more difficult to get back full ROM and strength.

Maximal function after patellar fracture is usually not achieved until 1 year after sugery.42 Stiffness and anterior knee pain especially with stair climbing or prolonged sitting with the knee flexed are common.* Total patellectomy patients can have an extension lag. Around 70% to 80% of patients with ORIF will end up with a good to excellent result and 20% to 30% with a fair to poor result.3 A loss of 20% to 49% of extensor mechanism strength can be expected.36,43,44 About 70% of patients followed long-term will have some complaint about the knee. Long-term results after total patellectomy range from 22% to 85% (good to excellent) and 14% to 64% (fair to poor).†

The therapist should call the surgeon with any signs of wound infection. Wound infections after ORIF in patella fractures need to be dealt with quickly because the hardware is superficial and can easily become infected, which can lead to a deep infection requiring long-term antibiotics.

If in the course of therapy the patient develops an extension lag greater than he or she had earlier in rehabilitation, the surgeon should be called because a loss of fixation has possibly occurred. To help confirm this, the fracture site can be palpated for a gap.

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

The treatment of patients who have undergone ORIF for patella fractures requires a cooperative approach from the orthopedist and the physical therapist (PT). This concept is most evident when considering the challenge in treating patients after surgery. The goal of treatment is to provide a structurally stable patellofemoral joint and allow for full functional recovery of the involved LE. Factors that influence the choice of treatment include the following:

1 The overall health of the patient and the way it may influence wound and fracture healing

2 The location and configuration of the fracture

4 Patient compliance with the prescribed treatment plan (home program)

Although rehabilitation after a patella fracture treated with ORIF is crucial, a wide range of protocols may be used depending on the factors listed previously, the physician’s chosen fixation technique, and the patient’s goals (which differ among athletes, sedentary adults, and children). The information the PT collects from both the physician and the patient aids in determining the design and time parameters of the rehabilitation program.

The remainder of this chapter deals only with the simple transverse fracture. However, the clinician is reminded to respect the previously discussed four factors influencing treatment when planning rehabilitation for all patella fractures.

Phase I (Acute Phase)

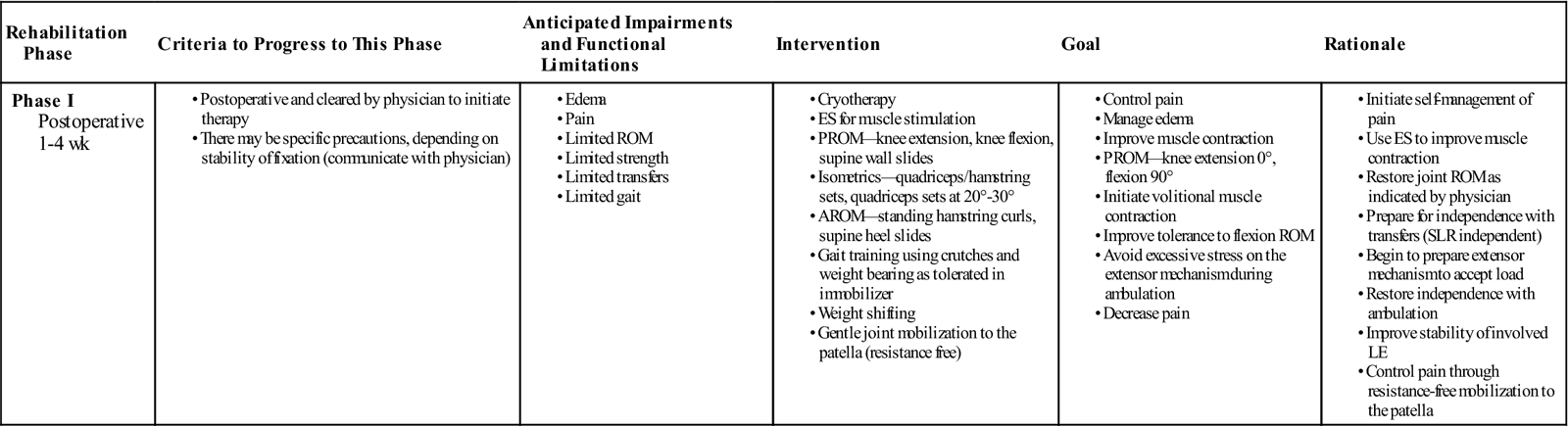

TIME: 1 to 4 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Control pain, manage edema, gain 0° to 90° of PROM, improve quadriceps and hamstring contraction (Table 26-1)

TABLE 26-1

Patella Open and Reduction Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase I Postoperative 1-4 wk |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

The acute phase of rehabilitation (the first 4 weeks) after ORIF of the patella is the time when reinjury is most likely. Attention to detail and communication with the treating physician are crucial during this period.

Controversy exists over when to initiate ROM. Hung and colleagues10 initiate knee motion 1 week after surgery, whereas Lotke and Ecker47 often immobilize patients for as long as 3 weeks before beginning any type of motion. Bostman and associates9,13 not only immobilize their patients an average of 38 days but also state that they see no correlation between the initial time of immobilization and the final outcome. Biomechanical studies that have demonstrated the appropriateness of tension band wiring and early ROM have generally used a simple transverse fracture pattern as the model.48 Complications such as poor bone quality and comminuted patella fractures may prevent the desired fixation and thus preclude any early joint ROM.

The PT performs an evaluation on the first postoperative visit, respecting the surgical procedure and any restrictions noted by the surgeon. Observation of the surgical site is documented and continually assessed to prevent wound complications.

![]() If the surgical site shows any signs of infection, then the PT should notify the surgeon immediately. Crutches are used postoperatively, and weight bearing is as tolerated with the immobilizer in place. Patients may eventually progress to independent ambulation (with the immobilizer still in place) after they tolerate full weight bearing (FWB) and are cleared by the physician (usually between 3 to 6 weeks). Smith and associates20 reported four complete failures after ORIF with tension band wiring. No inadequacies were detected during the initial procedures, and all four failures resulted from falls while walking unprotected in the early postoperative period.

If the surgical site shows any signs of infection, then the PT should notify the surgeon immediately. Crutches are used postoperatively, and weight bearing is as tolerated with the immobilizer in place. Patients may eventually progress to independent ambulation (with the immobilizer still in place) after they tolerate full weight bearing (FWB) and are cleared by the physician (usually between 3 to 6 weeks). Smith and associates20 reported four complete failures after ORIF with tension band wiring. No inadequacies were detected during the initial procedures, and all four failures resulted from falls while walking unprotected in the early postoperative period.

ROM measurements of the knee are taken passively, with the PT again observing any restrictions. Quality of muscle contraction in the extensor mechanism is noted, and active knee flexion is assessed. Girth measurements may be taken to assess atrophy of the thigh and calf; however, this has little overall benefit compared with functional assessment.

Early ROM is the goal in any operative treatment of patella fractures, yet the definition of early ROM varies, depending on who performs the procedure.9,10,13,47 Although the acute phase of rehabilitation tends to focus on knee joint range, gait deviations can produce problems later in rehabilitation if they are not addressed early. Patients often are treated in some type of immobilizer. A hinged brace can be used to allow for motion while stabilizing the fracture.

Initial treatments focus on restoring ROM (0° to 90°), improving quadriceps activation and hamstring muscle control, progressing gait (weight-bearing tolerance), managing edema, and controlling pain. A program of elevation and ice (20 to 30 minutes three times a day) is used as necessary to manage edema and control pain.

![]() Electrical stimulation (ES) for pain control is avoided because of the proximity of the screw and wires. However, ES can be used to assist in quadriceps contraction when appropriate. Gentle mobilization (grades 1 and 2 shy of resistance) of the patella also is used to control pain.

Electrical stimulation (ES) for pain control is avoided because of the proximity of the screw and wires. However, ES can be used to assist in quadriceps contraction when appropriate. Gentle mobilization (grades 1 and 2 shy of resistance) of the patella also is used to control pain.

Initial exercises of the knee involve PROM, limited active range of motion (AROM), and isometrics. Passive stretches are performed to restore flexion and extension. The vigor of the stretch should be in concert with the guidelines established by the surgeon. In general, patients are expected to reach 90° of flexion and full extension by 4 weeks. Supine wall slides can be easily performed in the clinic or at home. (See the section on Suggested Home Maintenance for the Postsurgical Patient.) Regaining full extension is usually not a problem; however, limitations of extension can be treated quite successfully.

Active exercises primarily focus on using the hamstrings to flex the knee. Heel slides and standing hamstring curls are initiated to aid in increasing muscle control and progressing ROM.

Isometric exercises involve quadriceps and hamstring cocontraction and isolated quadriceps contractions at 20° to 30° flexion. Quality is observed and ES is helpful in recruitment.

Gait training focuses on increasing the acceptance of weight on the involved leg. Weight shifting can be given as part of the home program. After the incision is healed and the surgeon allows it, aqua therapy can be initiated with an emphasis on proper weight shifting and gait mechanics.

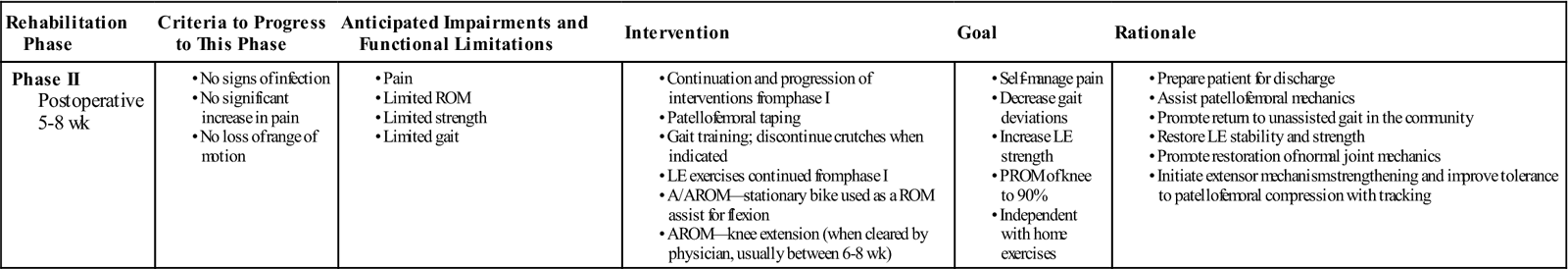

Phase II (Subacute Phase)

TIME: 5 to 8 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Self-manage pain, increase strength, increase ROM to 90%, initiate quadriceps AROM (6 to 8 weeks), have minimal gait deviations on level surfaces (Table 26-2)

TABLE 26-2

Patella Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase II Postoperative 5-8 wk |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

The subacute or midphase of rehabilitation (from weeks 5 to 8) is the transition from limited functional activity to aggressive functional activity. The actual exercise protocol is similar to any other type of patellofemoral rehabilitation. The only real difference with ORIF patella fracture is that a true fixation of the fracture has been obtained. Motion at the fracture site tends to activate secondary callus formation, especially with tension band wiring of a patella fracture. The danger in moving a nonfixated fracture (i.e., a fracture with no established callus formation) is that a nonunion may develop. A nonunion of bone is caused by excessive motion directly at the fracture site, which keeps the callus from forming sufficiently. This underlines the importance of maintaining immobility in some patella fractures during the rehabilitative process.49

Another factor to consider is that patella fractures involve joint surfaces. Incongruency of the articular surfaces can lead to articular cartilage degeneration and possible early arthritis if not treated. Incongruity of the patellofemoral joint may alter the joint mechanics, producing areas of noncontact or excessive pressure over the patella.50 Issues of patellofemoral contact area and joint reaction force must be evaluated during this phase of rehabilitation. The use of patellofemoral taping (see Figs. 20-1 to 20-3) can be useful in limiting imbalances over the fractured surface of the patella. By this phase, the patient is demonstrating increased competency in ambulating with the brace and decreased reliance (if any) on the crutches. Exercises are progressed as in phase I, and the patient is instructed to perform two sets per day (repetitions to fatigue). Closed-chain exercises are initiated on a progressive basis based on patient healing and quadriceps and LE control.

Modalities at this stage are primarily ice for pain control. ES of the quadriceps is continued as indicated to progress muscle recruitment. Moist heat can be used to prepare the knee for stretching after edema is controlled.

PROM stretches are progressed as indicated to obtain full flexion. The vigor of grades of mobilization is increased into resistance as indicated. AROM for the quadriceps is initiated between 6 to 8 weeks (or when the fracture is deemed stable enough to tolerate it). The stationary bike can be used as a ROM assistive device and progressed for strengthening and cardiovascular purposes after flexion allows full revolution without hip hiking. Surgeon approval is required before initiating resistance training on a bicycle.

The rehabilitation at this point begins to mimic that prescribed for the patient recovering from lateral release in terms of exercises and progressions. Taping can be initiated in this phase as deemed appropriate by the therapist.

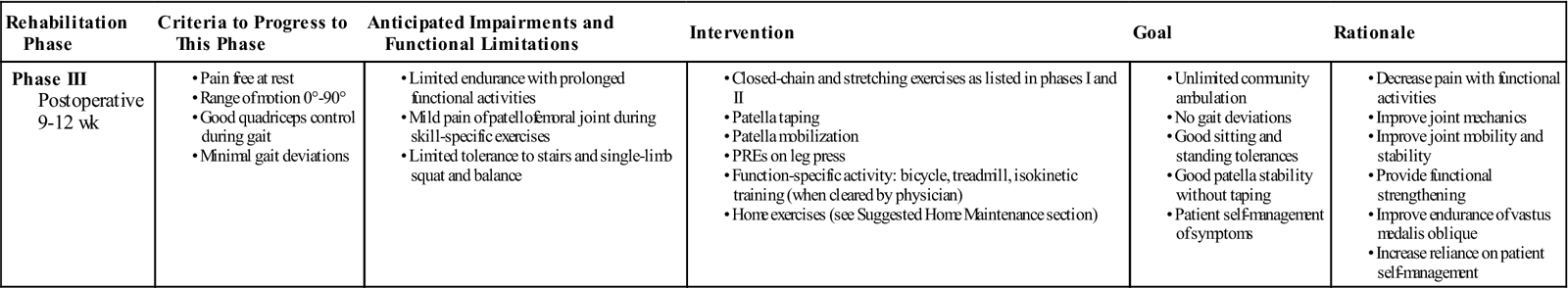

Phase III (Advanced Phase)

TIME: 9 to 12 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Return to full function, develop endurance and coordination of the LE, continue to address limitations with steps and running (with physician clearance) (Table 26-3)

TABLE 26-3

Patella Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase III Postoperative 9-12 wk |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

The advanced stage of rehabilitation (from weeks 9 to 12) focuses on functional, skill-specific activity. Most of the effort and work is spent on building back the patient’s quadriceps, hamstring, and gastrocnemius-soleus muscle strength.

Depending on remaining deficits, exercises from the previous two phases are continued. The therapist should keep in mind that the time frame will vary depending on many factors, including type of fracture, fixation, and the patient’s response to rehabilitation.

![]() Furthermore, isokinetics should be avoided until the physician approves them. The need for taping should be minimal, but if continued taping is needed, patients are instructed in self-taping techniques. Monitoring for pain and joint effusion gives the therapist feedback on the way to progress activities aggressively. Long-term strengthening of the muscles surrounding the patellofemoral joint with the development of endurance and coordination over time are the goals of this phase.

Furthermore, isokinetics should be avoided until the physician approves them. The need for taping should be minimal, but if continued taping is needed, patients are instructed in self-taping techniques. Monitoring for pain and joint effusion gives the therapist feedback on the way to progress activities aggressively. Long-term strengthening of the muscles surrounding the patellofemoral joint with the development of endurance and coordination over time are the goals of this phase.

By this stage, patients should be close to discharge because they are fairly functional with sitting, standing, and walking tolerances. Limitations with stairs and squatting activities continue to be present. Prolonged standing and walking should be continually improving, with the focus on a progressive increase in activities. Running and jumping should be initiated on an individual basis as determined by the surgeon (potentially after removal of hardware).

Suggested Home Maintenance for the Postsurgical Patient

An exercise program has been outlined at the various phases. The home maintenance section outlines rehabilitation guidelines the patient may follow. The PT can use it in customizing a patient-specific program.

Troubleshooting

Issues that prevent a successful outcome are unstable fixation, incongruous reduction, poor patient compliance, and delays in early PROM exercises. Patients with poor pain tolerance do not regain strength and ROM as easily and may be left with residual deficits. Return of maximal function after a patella fracture can take as long as 1 year.10 Residual problems of anterior knee pain and stiffness are common complications.* An estimated 70% to 80% of patients recovering from patella ORIF have good to excellent results, although 20% to 30% have fair to poor results.3 Residual loss of extensor strength has been recorded in the 20% to 49% range.

Prolonged immobilization is detrimental to the final result regardless of the treatment.3 Although it produces a risk of wound infection, the benefits of ROM outweigh the risk of wound complications. However, this situation is especially tenuous in patients who suffer open patella fractures because they are at a higher risk for infection.

Clinical Case Review

1James is 45 years old and had patella ORIF 3 weeks ago. He arrives for his initial evaluation in an immobilizer with his incision well healed. He weighs 250 lb and is 5-feet 10-inches tall. What modality and procedures would be most appropriate to improve his gait pattern?

Given his size, pool therapy would be the most appropriate tool to improve his gait pattern and limit body weight stress on the patella. Warm water can help improve ROM and decrease pain, and stresses that land-based therapy place on the joint.

2Meghan is 25 years old and had patella ORIF 6 weeks ago. She has only 60° of flexion and guards with any attempts at manual therapy (soft tissue mobilization, joint mobilization) to improve ROM. The “end feel” of her flexion is a soft end feel that does not provide much resistance (no catching or hard end feel). She also has been negligent in performing her home exercise program. What changes did the therapist suggest to improve Meghan’s outcome?

Meghan was instructed to, when possible, take her pain medication before coming to therapy. The therapist also explained that 20% to 30% of patients have a “poor” outcome. If her case was to be successful (and the surgeon saw no reason why it should not be), then she must gain flexion ROM. At some point she needs to take responsibility for her care. After this intervention, her ROM improved as did her tolerance to manual techniques.

3Jessica is 40 years old. She fractured her patella when she fell off a footstool and onto her knees. She had a patella ORIF surgery 9 weeks ago. Her knee flexion ROM is limited, and peripatella pain is a factor when performing ROM stretches. ROM exercises for knee flexion have been emphasized during the past few treatments along with modalities for pain control. Little progress has been noted. What treatment techniques may be the most helpful?

The PT should assess the patellofemoral and the tibiofemoral joints for limited mobility. If mobility is limited, which is likely, then patella mobilizations using grades into resistance (grades 3 and 4) can be helpful. The therapist should receive clearance from the physician before initiating mobilization into resistance. If it is limited, then increasing inferior patella movement may particularly help knee flexion ROM. The patellofemoral contact area and reaction forces also must be evaluated. Patellofemoral taping can be useful in limiting imbalances over the fractured surfaces of the patella. Complaints of pain with flexion may decrease, particularly with closed-chain exercises. If restrictions are found in the tibiofemoral joint, mobilizations (grade 3 and 4) can be performed to increase flexion (posterior glides of the tibia on the femur).

4Jessica’s knee ROM is now full 12 weeks after surgery. She performs a series of exercises for leg strengthening. She begins by stretching her hamstrings and gastrocnemius-soleus muscles. She then performs the following:

• Standing minisquats against the wall

• Leg presses using 100 lb and keeping knee flexion less than 60°

• Lunges with 5-lb weights in a long-stride position

• Wall slides between 0° and 45° with a 1-minute hold

• Standing (four-wall) elastic tubing hip flexion, abduction, and adduction on the uninvolved side

• Step-downs on an 8-inch step, holding contraction until the heel of the opposite leg makes contact

Although she has minimal discomfort during the exercise regimen, she has increased complaints of pain for 2 days after the exercises. Which of these exercises is most likely to be an aggravating factor?

The 8-inch step-downs are the most aggressive exercises because they produce the highest patellofemoral compression forces. The knee is most likely flexed beyond 50° while performing an eccentric contraction during FWB on the affected extremity.

5David is 3 weeks after surgery and just started therapy. He has been a patient in the past and his pain tolerance is not that good. He notes a constant 5/10 pain in his knee without evidence of infection or instability of the repair. What pain management techniques can be used?

ES for pain control is avoided because of the proximity of the screw and wires. However, ES can be used to assist in quadriceps contraction when appropriate. Gentle mobilization (grades 1 and 2 shy of resistance) of the patella also is used to control pain in addition to ice and elevation.

6George is 7 weeks postoperation and has limited tolerance to weight bearing because it causes some increased pain around the patella. What procedures/techniques can be used to assist in managing his symptoms?

The use of patellofemoral taping can be useful in limiting imbalances over the fractured surface of the patella. By this phase, the patient is demonstrating increased competency in ambulating with the brace and decreased reliance (if any) on the crutches.

7Lissette is 12 weeks postoperation and is frustrated that she is not able to return to running activities because of pain. What can be done to assist the patient with return to prior activities.

First and foremost the therapist should keep in mind, and educate the patient, that the time frame to return to prior activites will vary depending on many factors, including type of fracture, fixation, and the patient’s response to rehabilitation. Accomplishing this early on and setting interim goals (i.e., partial weight bearing to FWB, double- to single-leg squat, single-leg squat with 50% body weight to 100% body weight) are helpful. Monitoring for pain and joint effusion gives the therapist feedback on the way to progress activities aggressively. Long-term strengthening of the muscles surrounding the patellofemoral joint with the development of endurance and coordination over time are the goals of this phase.

8George is 12 weeks postoperation and has made slow progress (0° to 115°, fair quadriceps contraction, residual mild antalgia during gait/single-limb stance). What instructions can you give him to be successful over the next 6 months?

Patients with poor pain tolerance do not regain strength and ROM as easily and may be left with residual deficits. George was instructed to continue his home stretching/strengthening program with monthly reassessments. Return of maximal function after a patella fracture has been noted to take as long as 1 year.