Passing Clinical Examinations

BACKGROUND

Clinical examinations come in all shapes and sizes. Most medical students focus on their licensing or ‘final’ exams, doctors in training on exams testing further skills, such as the MRCP, or those that provide specialist status, such as the Boards in the United States.

The examiners in all these examinations have the same objective: to test the candidates’ competence in areas that are important in clinical practice. In devising the examination format, the examiners are aware that:

Thus, examiners continually amend the format of the examination so that it is more valid, more reliable and more closely aligned to clinical practice. Currently the trend is away from ‘spot diagnosis’ to an observation of limited focused clinical examination. This aims to replicate what happens clinically, and to encourage candidates to learn the skills they will need in practice.

These examinations have differing formats but almost all include a requirement for the candidate to perform the following stages:

• Stage 1: Examine a patient neurologically, observed by an examiner.1 The examiner will be looking for a systematic, appropriate and thorough neurological examination, using reliable examination technique. They will also observe for communication skills, including rapport with the patient, professional manner and treating the patient with appropriate consideration and empathy. In other words, ‘what you do’.

• Stage 2: Describe the findings, coming to some sort of conclusion.1 The examiner will be looking for a correct identification of abnormal physical signs, an appropriate interpretation of these abnormalities, and a reasonable synthesis of the findings and suggested diagnoses and differential diagnosis. In other words, ‘what you find’ and ‘what it means’. Interpreting the signs depends on getting the signs right and this will depend on having done the examination properly—so stage 2 depends on stage 1.

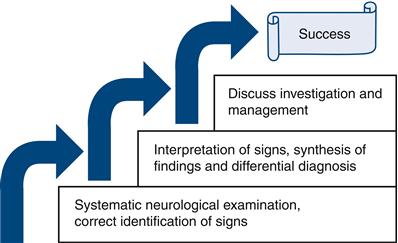

• Stage 3: Discuss the further investigation or management of the patient’s problem.1 The examiner will discuss aspects of further investigation and management. This tests the candidate’s knowledge relating to this particular clinical problem. This is not the focus of the clinical part of the examination, as this knowledge is often tested using other examination formats. Discussing these elements further depends on having an appropriate diagnosis or differential diagnosis—so stage 3 depends on stage 2, which depends on stage 1 (Fig. 29.1).

Figure 29.1 Three steps to success

Most candidates run into problems with stages 1 and 2, and may not get to stage 3. The examiners may try to help, with prompting or leading questions (let them).

The best way to pass the exam is to be competent. This is why this chapter is at the end of the book. So, if you turned straight to this section, go right back to the beginning of the book (unless it’s an emergency2).

WHAT TO DO

Consider each stage of the examination in turn.

Stage 1: Examine a patient neurologically, observed by an examiner

You are not meant to reach a stunning diagnosis but to demonstrate that your examination is:

The difficulties arise because:

• you are unable to undertake a systematic, practised, reliable, appropriate and thorough examination

The solution is to sort out the first point; when competent at examination, you will use time more efficiently and become confident.

Systematic, practised and reliable

This book is set out to allow you to develop a systematic approach to clinical examination using reliable methods.

To develop a system you can rely on, you need to practise. Professional golfers practise hitting the ball thousands of times on the driving range so when under pressure in competition they know just what to do. Neurological examination is just the same. What you need to do has been described throughout the book; the more you do it and the quicker you become, the less you are concerned about what you should do next and the more confident you are in your findings being normal or abnormal. Generally speaking, you will also look slicker.

Practising with someone watching you can help this further—preferably someone more experienced, but colleagues can also help. Think about ‘demonstrating’ physical signs so that your spectator will also see any abnormalities you find. You can learn by watching— anyone; you often learn as much watching someone having difficulties doing something as watching an expert. You will also be less anxious in the exam if you are used to being watched.

Appropriate and thorough

In some clinical examinations you are asked to do only a partial examination and are usually provided with only a limited history: for example, ‘Please examine this man, who has had progressive difficulty walking over the last year.’ This is not as artificial as it seems. In clinical practice most patients will have one problem that will be the focus of the neurological examination and the rest of the neurological examination is effectively a screening examination. You should therefore be able to work out what is ‘appropriate’ in the context of the exam (Table 29.1). It is useful to think of ‘appropriate’ in this context as ‘what is needed to solve the clinical problem’.

Table 29.1

| Clinical problem | Focused examination | Common syndromes |

| Walking difficulties | GaitMotor system; tone, power; reflexesSensationCoordinationConsider: fast repeating movements; eyemovements; speech | Cerebellar syndromeAkinetic rigid syndromeSpastic paraparesis (with or without sensory signs)Peripheral neuropathy |

| Numb hands and feet and loss of dexterity | GaitMotor system; tone, power; reflexesSensationCoordination | Spastic tetraparesis with sensory signsPeripheral neuropathy |

| Weakness in arms and legs | GaitMotor system; tone, power; reflexesSensationCoordination | Spastic tetraparesis with or without sensory signsMixed upper and lower motor neurone syndromePeripheral neuropathy |

| Speech difficulties | SpeechFaceMouth | DysarthriaDysphoniaAphasia (less likely) |

| Double vision | Eye movements | Cranial nerve lesion VI, III or IVMyasthenia gravisThyroid eye disease |

| Visual problems | AcuityFieldsFundiPossibly eye movements | Optic atrophyHomonymous hemianopia Bitemporalhemianopia |

A systematic examination that is appropriate will inevitably be thorough; that is, it will cover all the necessary parts of the examination. It does not have to be obsessional or fussy to be thorough; indeed, this would waste valuable time.

Professional

Be polite, courteous and considerate—as you should be with all patients (and colleagues!).

Stage 2: Describe your findings, coming to some sort of conclusion

The examiners will have watched you examine the patient and will have a reasonable idea of what you have found (demonstrated). They will ask you to describe your findings or conclusions—remember to answer the question they ask. How you answer will also depend on the level of the exam you are taking. There are three approaches:

1. To describe the physical signs systematically (A), using the conventional order, summarising them (B), then coming to a synthesis of the signs (C) and suggested differential diagnoses (D)—as in Boxes 29.1 and 29.2. This is long-winded, but allows you to describe the physical signs and your reasoning. This approach is generally restricted to final medical student examinations.

2. To summarise the relevant abnormal signs (B), a synthesis of the signs (C) and suggested differential diagnosis (D)—as in Boxes 29.1 and 29.2. This is more succinct and gives the opportunity to discuss and clarify signs before coming to a synthesis. If these are not quite right, the examiner may wish to prompt you towards the correct interpretation.

3. To propose a synthesis of the signs (C), with or without reference to abnormal signs (± B), and discuss a differential diagnosis (D)—as in Boxes 29.1 and 29.2. However, if signs or synthesis are incorrect, it is more difficult for the examiner to prompt with questions.

Approach 2 is probably the correct strategy in postgraduate examinations if no specific question is asked.

It is worthwhile practising each of these approaches when you see patients and actually to say them out loud—preferably to a more senior colleague; a contemporary will also be able to offer advice. If no one else is there, do it anyway, to practise putting your thoughts into words.

When coming to a synthesis, describe the anatomical or syndromic diagnosis first. Then offer a differential diagnosis of potential causes. You can classify potential causes according to their pathological process rather than specific diseases. Start with common causes; if you suggest a rare cause you might want to tell the examiners you appreciate that it is rare. The examiners are interested in your clinical reasoning, so part of the test is to see how you approach the differential diagnosis.

N.B. Euphemisms: If the discussion occurs while the patient is there, you will be expected to use euphemisms for diagnoses you discuss that are potentially alarming for the patient (especially if they have something else). Examples include: demyelination for multiple sclerosis; anterior horn cell disease for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (motor neurone disease); neoplasia for cancer.

Some common or important conditions you might want to practise on are:

Stage 3: Discuss the further investigation or management of the patient’s problem

This part of the clinical exam primarily aims to test whether you are sensible and have good ‘clinical sense’, and does not depend on a wealth of knowledge (though this will help). Knowledge is tested more extensively in other parts of your exams.

Remember that this examination is trying to replicate real clinical practice—so do what you would do in real life. If you have only had a limited history and been able to do a partial neurological examination, you would normally take a full history and complete examination. Suggest this, but indicate what particular aspects you would focus on; for example, in a patient with a neuropathy you might suggest that you would be interested in general medical history, drug or toxin exposure, alcohol intake and detailed family history.

If you are asked about other investigations, indicate how you would use the investigations to solve the clinical problem—why would you do each test? Remember the tests are there to help you—how would they help you?

When suggesting investigations, generally start with the simple ones. However, if there is a specific complicated test that would solve the problem, that is the one to do (e.g. genetic testing is the best way to confirm the diagnosis of myotonic dystrophy).

Discussing management in the very limited time available is easiest if you have a mental framework to help you. Almost all management plans can be divided into:

Boxes 29.3 and 29.4 give some examples of how to use this approach.

LEARNING NEUROLOGICAL EXAMINATION IN A CRISIS

Hopefully very few readers will need this section, having learnt neurological examination through their training. Many students and junior doctors become anxious as they approach exams; however, they are usually a good deal more proficient than they think they are. Most can make great strides with only a little help, usually in organising their thoughts. If students get themselves into this predicament, it is often through a reluctance to practise something they feel incompetent doing.

However, sometimes people do find themselves in a fix. Proper preparation is not possible as the exam is next week. If so, this is what you need to do:

• Find one or more friends to act as examination partners to learn with you.

• Buy two (or more) copies of this book.

• Give one to each friend and read it from cover to cover (one evening).

– Other cranial nerves: Chapters 5, 6, 11–14.

– The motor system: Chapters 4, 15–20.

– Limb sensation: Chapters 21, 22.

– Coordination and abnormal movements: Chapters 23, 24.

• Take it in turns to examine and to watch and advise until you are all confident with each chapter. Then practise conducting a standard examination (Chapter 28).

Having become familiar with the methods, now try to see as many patients with neurological problems as possible, again observing each other. After each examination, summarise the physical signs, come to a synthesis and differential diagnosis, and discuss the investigation and management with your examination partner, or even better with a more experienced doctor, if you can find one.

Patients are almost always keen to help. Patients with long-standing neurological problems will often be expert at being examined and are often particularly helpful.

When not seeing patients, practise describing the physical findings of imaginary patients with classical diseases and discuss their investigation and management with your examination partner.

TIP

TIP