7 Parkinson’s disease and related conditions

Introduction

Incidence

It is unusual to find PD diagnosed before the age of 50 but the prevalence increases with age, becoming as high as 4% in older age groups, particularly in more industrialized countries. The incidence of PD in the UK is 18 per 100 000 population per year, amounting to approximately 10 000 new cases each year [1]. Sex distribution is approximately equal.

Risk factors

The root cause remains obscure but parkinsonism results from many different pathological processes, including ageing, environmental and genetic factors. Ageing is not thought to be a primary cause of PD, although the substantia nigra containing dopamine-producing neurons declines with age. It is possible that injury or infection in early life may predispose the patient to accelerated loss of this tissue. It has been suggested that PD can be a side-effect of certain psychotropic drugs [2]. Analytic studies generally reveal an inverse association between PD and cigarette smoking, although epidemiologic evidence does not support a direct protective effect of smoking [3].

It has also recently been suggested that gout can protect from PD. The value of the increased uric acid present in the system needs to be fully evaluated but first results are interesting [4]. The association between ischaemic stroke, vascular risk factors and PD has been addressed in several studies [5].

There has been some argument over the years about other similar pathologies, known as vascular parkinsonism. The condition has been named and renamed several times, with terms such as arteriosclerotic parkinsonism, arteriosclerotic pseudoparkinsonism and lower-body parkinsonism. Despite the progress in our understanding of other parkinsonian syndromes, such as progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple-system atrophy, and significant developments in neuroimaging techniques, the concept of vascular parkinsonism is still unclear and the clinical diagnosis is often difficult [5], but from a physiotherapy or acupuncture perspective it does not differ greatly from PD.

Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis

The definitive symptoms of PD are tremor at rest; involuntary trembling in the hands, arms, legs or jaw; rigidity or stiffness of the limbs and trunk; a general slowness of movement (bradykinesia); and impaired balance and coordination, often involving postural instability. ‘Dropped-head’ syndrome is characterized by severe neck flexion but minor thoracic or lumbar curvature. It results from neck extensor weakness or increased tone of the flexor muscles. This symptom is usually reported in neuromuscular diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, myasthenia gravis and polymyositis or in extrapyramidal disorders, but does also occur in PD [6].

In addition to these motor changes, there may be other symptoms, including depression and other emotional changes; difficulty in swallowing, chewing and speaking; urinary problems or constipation; skin problems; and sleep disruptions. There is noticeably decreased facial expression, apathy, fatigue and sometimes pain. This fatigue, combined with worsening functional status, can be a significant contributor to poor quality of life [7].

Some cognitive changes can be suspected early in the disease, particularly frontal lobe executive dysfunction. Parkinsonians find it difficult to turn thought into action. A slowing-down of mental processes is sometimes mistaken for dementia, but as a rule of thumb, if you give a Parkinson’s patient time to answer a question, he or she will answer. A patient suffering from Alzheimer’s will tend to forget the question. As the disease develops psychiatric problems can dominate the clinical picture. Depression is the most common of these, with about a third of patients suffering from depression at some stage in their disease [1].

Medical treatment

Surgery

Surgery was in vogue for PD before the 1970s but became less popular until recently. It may be appropriate if the disease fails to respond to drugs or the effect of the drugs diminishes. Transplanted fetal mesoencephalic cells, harvested from aborted fetuses, grown in cell culture and injected into the brain in a form of cell suspension, have been shown to replace the production of natural dopamine, producing some good results, although the technique itself remains controversial [8]. A technique called deep-brain stimulation uses electrodes implanted into the brain and connected to a small pulse generator which can be externally programmed. This can decrease the need for some of the drugs, reducing the unwanted side-effects, most often the increased involuntary movements associated with levodopa [9]. The deep-brain stimulation can also reduce the fluctuation of symptoms, allowing for greater freedom of movement generally. Early results have been good but the technique is not yet widely used.

Prognosis

Impact on patient

PD is similar to other neurological problems in that it varies widely from patient to patient. With some the tremor is the most limiting factor while others seem untroubled by that, but far more concerned by their lack of mobility or difficulty communicating by facial expression. Clinical experience suggests that there is, however, a great deal of unreported depression and often quite a lot of pain brought about by the rigidity and overall poverty of muscle movement [10].

When investigating the lifestyle impact of PD, Kuopio et al. found that women scored significantly lower on five of the eight dimensions of the SF-36 outcome measure. This study found depression to be more common among women than men [11]. They concluded that, to improve the quality of life in PD patients, it is necessary to recognize and treat the depression. Parkinsonian symptoms and symptoms of autonomic dysfunction such as constipation and sexual impotence in males predominate early in the course of the disease and certainly have an effect on mood. Constipation may be unrelenting and hard to manage in some patients.

Parkinson’s disease and physiotherapy

Exercise has long been a popular form of treatment with physiotherapists, although the effects seem to be best in the short term. A recent study by Morris et al. [12] confirms this. For the exercise group, quality of life improved significantly during inpatient hospitalization and this improvement was retained at follow-up. Inpatient rehabilitation produced short-term reductions in disability and improvements in quality of life in people with PD. Exercise training has also been found to decrease significantly the number of falls experienced by these patients [13]. Other techniques, including auditory cues [14] or the use of treadmills, have been tried with some success [15], but all the studies were relatively small and none appear to hold the key. As a novel way of combining both forward and backward walking in a pleasurable environment, tango lessons have been investigated, with some success [16].

The Royal College of Physicians guidelines have recommended the following:

All of the above will be tackled in a course of physiotherapy treatment at any stage of the disease but the addition of acupuncture may be of considerable benefit. There have been several studies investigating the effect of acupuncture on the symptoms of PD and a recent systematic analysis summed the situation up well, concluding that ‘there is evidence indicating the potential effectiveness of acupuncture for treating idiopathic PD’. The review found that, out of the 10 trials selected, nine claimed a statistically positive effect from the use of acupuncture [18].

Acupuncture in Parkinson’s disease

Acupuncture remains a popular treatment for PD in far-Eastern countries.

There has been a serious attempt to re-evaluate the traditional treatments in the light of modern knowledge, in particular the herbal remedies [19], but a scientific review of all TCM therapies in this context is now needed.

In a non-blinded pilot study, 85% of patients reported subjective improvement of individual symptoms, including tremor, walking, handwriting, slowness, pain, sleep, depression and anxiety [20]. There were no adverse effects; however there were only 20 patients in this study.

Some interesting work has been done by a Chinese research group, where electroacupuncture was applied at a frequency of 100 Hz at the points GV 20 and GV 14 to MFB transected parkinsonian rats who had rotenone (3 μg) administered bilaterally and stereotaxically into the medial forebrain bundle (MFB) to produce parkinsonian symptoms [21]. An extension of this work to human patients might produce significant results.

Nonetheless, the following sections will offer a selection of acupuncture points and techniques with varying rationales. The reason for point selection may ultimately be less important than the point itself. Table 7.1 gives a summary of expected symptoms.

Table 7.1 Symptom picture for Parkinson’s disease (including multiple-systems atrophy)

| Symptom | Characteristic presentation | Parkinson’s disease |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased mobility | Rigidity |  |

| Fatigue | Lack of energy |  |

| Respiratory problems | Snoring |

X, usually absent;  , common;

, common;

, very frequent.

, very frequent.

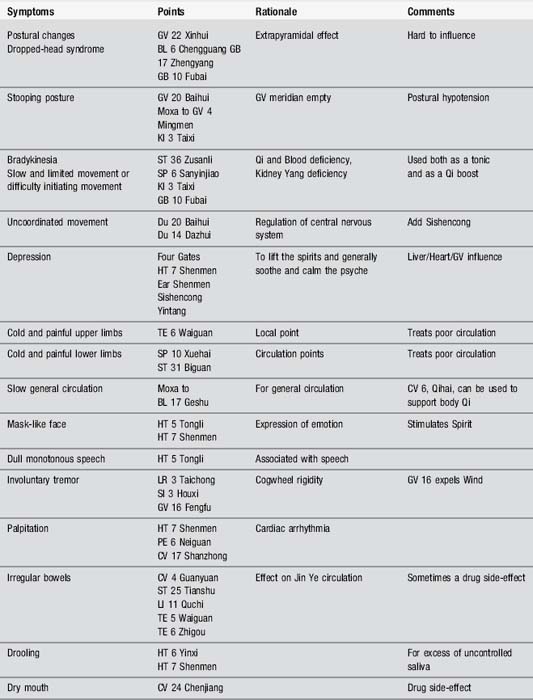

Body acupuncture

Acupuncture points, mainly on Yang meridians, can be used, as in all neurological diseases, to tackle the superficial musculoskeletal symptoms. Both pain and movement problems can be addressed. The points can be selected according to symptoms and Table 7.2 gives some of the alternatives. Many problems are directly caused by the medical interventions and these have also been listed. Electroacupuncture may be used at some of the points; the recommended frequency for body points is 2 Hz, while that for scalp points is 100 Hz.

Scalp acupuncture

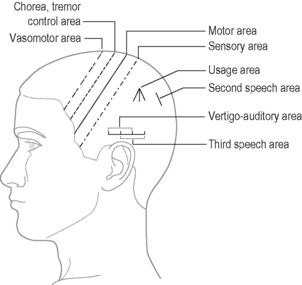

Perhaps surprisingly, scalp acupuncture is a technique frequently recommended for PD, in both Western and modern Chinese texts. This is a relatively modern idea and the technique claims to stimulate the surface of the brain, most particularly the sensory and motor cortices (see Chapter 12).

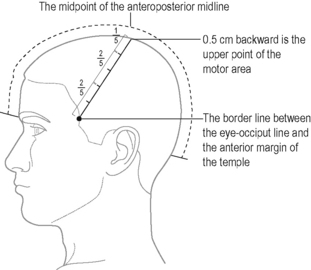

Points are located by identifying the anteroposterior median line as a reference (Figure 7.1).

In PD both motor and sensory lines should be treated with the addition of the chorea or tremor area (Figure 7.2).

Some studies [22] have used scalp and body acupuncture together as an addition to the drug regime and there has been some attempt to analyse what may be happening in the brain during scalp acupuncture in a Parkinson’s patient, particularly as regards dopamine production; however more work needs to be done [23].

Some authorities claim that scalp acupuncture used early enough can alleviate tremor without any additional drug treatment, but if the disease has been present for more than 2 years the improvement will only be temporary [24]. Once the patient has been taking regular drug medication for many years it would be unwise to try to replace this with acupuncture treatment.

TCM approach

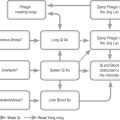

Which TCM syndromes may be involved? According to Maciocia, the most likely syndromes will be Qi and Blood deficiency, Phlegm Heat agitating Wind or Liver and Kidney Yin deficiency [25].

Due to the usual lack of homogeneity among patients suffering from any type of neurological disease, there may of course be wide variation. There are other techniques for dealing with the broad spectrum of symptoms, including a use of abdominal acupuncture only in addition to the normal drug regime. This has some logic; many of the side-effects of the drugs – fatigue, constipation, for example – could be lessened this way, but little work has been published so far and there are many flaws in the methodology of the best published study [26].

Phlegm Heat agitating Wind (affecting Liver)

Liver and Kidney Yin deficiency

Treatment

Nourish Yin, dispel Wind, energize the meridians.

It is important to remember that these patients are characterized by a slowing-down of body processes and a general lack of energy. Acupuncture can be a draining type of therapy and should be used with caution. However, it can be seen that, with a basic understanding of TCM, a useful prescription can be drawn up for a patient manifesting with a clear neurological disease process [27]. Then it would be sensible to select specific points for symptoms, ensuring that some of the powerful end points are also used. One good argument for using acupuncture for the management of PD might be that it causes fewer adverse effects than drug treatment, particularly levodopa, and often addresses some of the associated problems [28].

Case study 7.1: level 1 case study: PD immobility

Case study 7.2: level 3 case study

[1] Jones D., Playfer J. Parkinson’s disease. In: Stokes M., editor. Physical Management in Neurological Rehabilitation. Edinburgh: Elsevier Mosby; 2004:203-219.

[2] Keus S.H., Munneke M., Nijkrake M.J., et al. Physical therapy in Parkinson’s disease: Evolution and future challenges. Mov Disord. 2008;24:1-14.

[3] Schoenberg B.S. Environmental risk factors for Parkinson’s disease: the epidemiologic evidence. Can J Neurol Sci. 1987;14(3):407-413.

[4] De Vera M., Rahman M.M., Rankin J., et al. Gout and the risk of parkinson’s disease: A cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(11):1549-1554.

[5] Benamer H.T.S., Grosset D.G. Vascular parkinsonism: a clinical review. Eur Neurol. 2008;61:11-15.

[6] Kashihara K., Ohno M., Tomito S. Dropped head syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21(8):1213-1216.

[7] Havlikova E., Rosenberger J., Nagyova I., et al. Impact of fatigue on quality of life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(5):475-480.

[8] Hauser R.A., Freeman M.D., Snow B.J., et al. Long-term evaluation of bilateral fetal nigral transplantation in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(2):179-187.

[9] Liang G.S., Chou K.L., Baltuch G.H., et al. Long-term outcomes of bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2006;84(5–6):221-227.

[10] Findley L., Peto V., Pugner K. The impact of Parkinson’s disease on quality of life: results of a research survey in the UK. Mov Disord. 2000;15(3):179.

[11] Kuopio A.M., Marttila R.J.H.H., Toivonen M., et al. The quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2000;15(3):216-223.

[12] Morris M.E., Iansek R., Kirkwood B. A randomized controlled trial of movement strategies compared with exercise for people with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008.

[13] Ashburn A., Fazakerley L., Ballinger C., et al. A randomised controlled trial of a home based exercise programme to reduce the risk of falling among people with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(7):678-684.

[14] Nieuwboer A., Kwakkel G., Rochester L., et al. Cueing training in the home improves gait-related mobility in Parkinson’s disease: the RESCUE trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(2):134-140.

[15] Protas E.J., Mitchell K., Williams A., et al. Gait and step training to reduce falls in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation. 2005;20(3):183-190.

[16] Hackney M.E., Earhart M.G. Short duration, intensive tango dancing for Parkinson disease: An uncontrolled pilot study. Complement Ther Med. 2008;17:203-207.

[17] National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Parkinson’s disease: national clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2006.

[18] Lam Y.C., Kum W.F., Durairajan S.S.K., et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(6):663-671.

[19] Li Q., Zhao D., Bezard E. Traditional Chinese medicine for Parkinson’s disease: a review of Chinese literature. Behav Pharmacol. 2006;17(5–6):403-410.

[20] Shulman L.M., Wen X., Weiner W.J., et al. Acupuncture therapy for the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(4):799-802.

[21] Wang X., Liang X.B., Li F.Q., et al. Therapeutic strategies for Parkinson’s disease: the ancient meets the future – traditional Chinese herbal medicine, electroacupuncture, gene therapy and stem cells. Neurochem Res. 2008;33(10):1956-1963.

[22] Jiang X.M., Huang Y., Zhuo Y., et al. Therapeutic effect of scalp electroacupuncture on Parkinson disease. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2006;26(1):114-116.

[23] Jiang X.M., Huang Y., Li D.J., et al. Effect of electro-scalp acupuncture on cerebral dopamine transporter in the striatum area of the patient of Parkinson’s disease by means of single photon emission computer tomography. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu = Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2006;26(6):427-430.

[24] Lu S. Handbook of acupuncture in the treatment of nervous system disorders, PD. London: Donica Publishing, 2002.

[25] Maciocia G. The Practice of Chinese Medicine. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, 1994.

[26] Chen Xh, Li Y., Kui Y. Clinical observation on abdominal acupuncture plus Madopa for treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu = Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion. 2007;27(8):562-564.

[27] Hopwood V. Acupuncture in Physiotherapy. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann, 2004.

[28] Lee M.S., Shin B.C., Kong J.C., et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for Parkinson disease: a systematic review. Mov Disord. 2008;23(11):1505-1515.

[29] Yau P.S. Scalp-Needling Therapy. Beijing: Medicine and Health Publishing, 1990.