Parkinson’s disease and other akinetic rigid syndromes I

In 1817 James Parkinson wrote ‘Essay on the shaking palsy’. The clinical syndrome he described, with tremor, rigidity and slowness of movement, is referred to as Parkinsonism or an akinetic rigid syndrome. The most frequent pathological cause of this syndrome is Parkinson’s disease.

Clinical features

The classical features of Parkinson’s disease are TRAP:

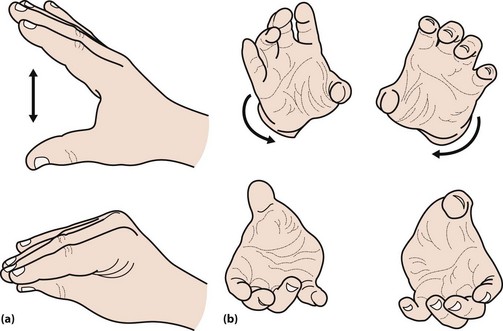

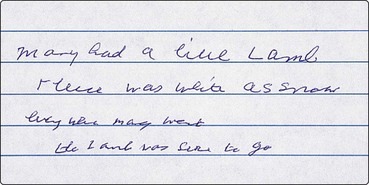

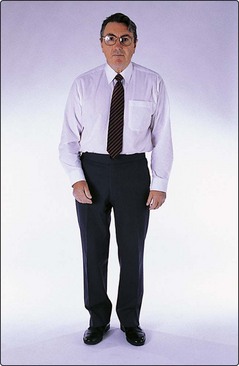

The face is immobile and the skin may appear greasy. There may be a dysarthria, with a monotonous voice that tends to trail off. Fast repeated movements tend to slow up, so-called bradykinesia. This can be tested by asking the patient to drum their fingers on a table or repeatedly bringing index finger and thumb together (Fig. 1). Writing becomes small and spidery (Fig. 2). The posture tends to become stooped and the patient stands with slightly flexed elbows (Fig. 3). On walking there is a loss of arm swing, the steps become shorter and there may be difficulty starting or stopping. The patient may be unsteady or fall on turning. This reflects the loss of postural reflexes; these can be tested by standing behind the patient and gently pulling the patient backwards. This would normally lead to a minor adjustment in posture, but a patient with altered postural reflexes may take multiple steps backwards. In more severe disease, there may be freezing – where the patient cannot start to walk – a form of akinesia. The gait may be festinant, where the patient cannot stop once started.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis depends on the pattern of the presentation. Tremor is one of the most common early symptoms. The main differential diagnosis is with essential tremor (p. 92). Essential tremor is not present when the limb is relaxed and at rest and is usually most prominent on sustained posture or with movement. However, if a patient voluntarily holds the hand in a resting position, a postural tremor may look like a rest tremor. Essential tremor may produce a yes–yes head tremor or titubation, and a trombone tremor of the tongue, features not seen with Parkinson’s disease.

The gait patterns most commonly mistaken for Parkinson’s disease are the ‘marche à petit pas’ of diffuse cerebrovascular disease and, less frequently, the apraxic gait of normal pressure hydrocephalus (p. 63).

In younger patients, Wilson’s disease is a rare but important differential diagnosis (p. 92).

There are a range of syndromes that share several features with Parkinson’s disease, but which have different pathological findings. These have been referred to as ‘Parkinson’s plus’ syndromes. These are all relatively rare. However, together there are a significant number of affected patients; indeed, in a series of 100 postmortem examinations of patients considered to have Parkinson’s disease, 20% were found to have other forms of Parkinsonism. The most common such syndromes are (i) multisystem atrophy, where there is autonomic failure, cerebellar signs and signs of upper motor neurone involvement, and (ii) progressive supranuclear palsy (or Steele–Richardson syndrome), where there is a supranuclear palsy (reduced ability to move the eyes voluntarily, with preserved movements on doll’s head testing; p. 19), prominent loss of postural reflexes and dysarthria. Both these syndromes tend to respond poorly to treatment and have a worse prognosis than idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. In initially assessing someone with suspected Parkinson’s disease it is therefore worthwhile testing eye movements carefully and measuring standing and lying blood pressure. In patients with a significant loss of higher function and prominent hallucinations on low-dose therapy, Lewy body dementia should be considered (p. 55). Given the common pathology, this probably reflects a different clinical manifestation of the same underlying disease.

Pathology and pathogenesis

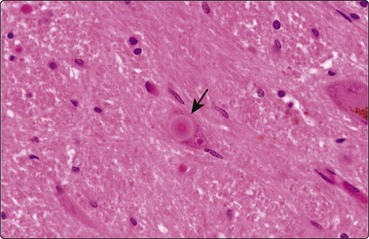

The characteristic pathological feature of Parkinson’s disease is the loss of the pigmented dopaminergic cells of the zona compacta of the substantia nigra. In some of the remaining neurones there are eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions called Lewy bodies which are made up of alpha-synuclein (Fig. 4). Similar changes are seen elsewhere in the brain stem, such as the locus ceruleus and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. The same pathology is seen through the cortex in Lewy body dementia.

The cause of Parkinson’s disease is not known. There are a few clues.