9 Parkinson’s disease

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) was first described by James Parkinson, the English physician after whom it was named, in his monograph on the ‘Shaking Palsy’ in 1817.1 While it occurs in 0.3% of the general population this climbs to 1% of those 60+ years old2 and up to 3% in patients aged at least 80 years.3

It is a progressive degenerative neurological disorder characterised by a tetralogy of symptoms, including tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability.4 The pathological features are loss of dopamine-producing neurons from the substantia nigra in the brainstem and other brainstem nuclei,5 together with Lewy bodies (ubiquinated protein deposits in the cytoplasm of neurons) and Lewy neurites (thread-like proteinaceous inclusions in neurites).6,7

PD is diagnosed on the basis of history and examination, rather than any specific blood test.8 The 2006 United Kingdom clinical guidelines suggest that PD requires specialist confirmation of diagnosis and subsequent follow-up.9 While there is good argument for the involvement of a neurologist, PD is a chronic illness with a predictably progressive decline so optimal care dictates a partnership between the specialist and general practitioner. As with all chronic illnesses, ideal care must accommodate lifestyle factors, careers and demonstrate an empathic approach, which is the forte of the general practitioner who is often more closely aligned with the patient and the home environment.

While the exact cause is unknown, a variety of genes have been identified from PARK1 at locus 4 q2110 through to PARK13 at locus 2 p1211 and the list is continuing to expand. This has special relevance when PD occurs in young patients, especially those younger than 50 years. It is hard to organise the tests in Australia but any condition with a potential genetic basis mandates discussion. The majority of cases of PD are sporadic and hence counselling will probably not alter the prevalence.

There was a major outbreak of Parkinsonism after the influenza epidemic (with encephalitis lethargica) in the early twentieth century, when lesions in the substantia nigra became apparent.12 Nevertheless the role of environmental factors was not fully appreciated until the 1980s when MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine), a by-product of synthetic opiate MPPP, a meperidine analogue designer drug, was reported to cause acute Parkinsonism in drug addicts in California.13 Since then it has been acknowledged that pesticides may cause Parkinsonism,14,15 thus various potential toxins can be avoided.

One may also consider lifestyle issues thought to protect against PD, such as smoking or taking of Chinese green tea,16,17 although smoking has sufficient other reasons to be avoided.

Making the Diagnosis

It can be seen that in the classical case the diagnosis has been offered on a platter, even before the patient has entered the consultation room when the formal process is supposed to start. The corollary of this is that one has to be acutely aware of what is on the platter to realise that the diagnosis is being offered, otherwise it may be missed and rely on someone else to show superior clinical acumen.

Taking a History

PD has been staged by Hoehn and Yahr4 (see Table 9.1) as starting with unilateral symptoms and signs through to serious disability. As the condition progresses a patient may report speech changes with softer, monotonous speech, possibly complicated by excessive dribbling or drooling. Patients may have problems initiating gait, having what is called ‘inertia’. These patients may report that they cannot get started when they want to walk but once they get going they seem to gain speed, even starting to run without wanting to, and may have difficulty stopping. They might develop techniques to stop, such as selecting a fixed object like a wall and walking into it to slow down their centre of gravity that they have been chasing.

| Stage 1 | Unilateral symptoms and signs |

| Stage 2 | Bilateral symptoms and signs |

| Stage 3 | Bilateral features with impaired postural reflexes causing disability |

| Stage 4 | Severe gait disturbance though still able to stand and walk without aids |

| Stage 5 | Inability to stand or walk without aids, wheelchair or bed-bound |

Posture, being bent in the middle and unable to stand up straight, may be a major symptom. Writing may be difficult, either due to the imposition of the tremor or patients may report their handwriting has become smaller, veering up and off the horizontal, hence becoming difficult to read even without tremor.

Often the patient will present with the complaint of tremor and will suspect the diagnosis of PD. Benign essential tremor is far more common than is PD, and the patient will be greatly relieved if given this diagnosis. It is therefore important to have simple tools with which to compare the two most common causes of tremor (see Table 9.2). A patient with PD may have both an essential and a PD tremor.

TABLE 9.2 Differentiating Parkinsonian tremor from essential tremor

| Characteristic | Parkinson’s disease | Benign essential tremor |

|---|---|---|

| Tremor location | Hands, legs, circumoral | Hands, head (titubation), voice |

| Laterality | Usually unilateral at onset | Usually bilateral |

| Bradykinesia | + | – |

| Rigidity | + | – |

| Family history | Usually – | + in ≥ 50% |

| Effect of alcohol | – | + (reduces tremor) |

| Age of onset | Usually > 60 years | Younger, ~40 years |

| Timing of tremor | At rest (when distracted) | With activity (rarely at rest) |

More recently there has been a realisation that PD may be associated with symptoms that transcend the motor features. These include neuropsychiatric symptoms, sleep disorders (such as REM sleep behaviour disorder), autonomic symptoms and sensory symptoms.18 Impulsivity, increased gambling and antisocial behaviour have been associated with PD and its treatment.19 The term ‘punding’ with associated compulsive sequenced behaviour is associated with PD. Impotence is reported by up to 60% of men with PD.20

Examination

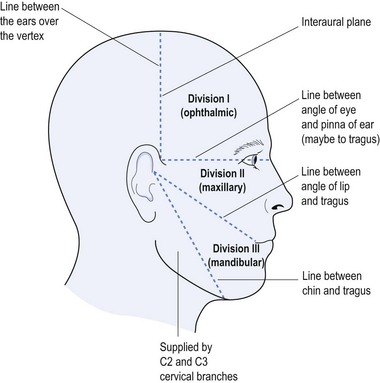

The tetralogy of principal features is well accepted (see Box 9.1) and available for examination. Working from the head downwards, the features include: positive glabellar tap (tapping the patient over the forehead above the bridge of the nose should only illicit three blinks—more than this is considered positive); paucity of blinking; difficulty with upward gaze; cog-wheeling of saccadic eye movements; decreased facial wrinkling with increased sebum in the skin, giving an oily appearance and looking younger than actual age; increased drooling; soft voice devoid of intonation; expressionless face; and possibly a posture with the head somewhat flexed forward. The patient may well have a positive palmar mental response (scratching the patient’s palm may elicit movement of the ipsilateral jaw, via the mentalis muscle) and is concurrent with other frontal lobe signs such as grasp reflexes.

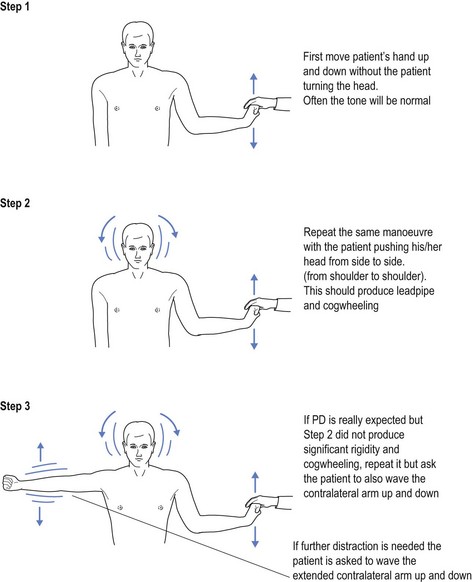

In the early stages of the disease tone may seem superficially normal. Once the patient is distracted, such as asking the patient to turn the head from side to side, it will exacerbate the increased tone, feeling like a lead pipe. With the superimposed tremor, this may feel like a cogwheel going over the cogs. To elicit this response the doctor flexes and extends the hand at the wrist while asking the patient to turn their head from side to side. This increases the tone as it allows the expression of resting tone. Without distraction the patient often tries to help, even without being aware of it (see Fig 9.1). In some cases there may be the need for further distraction, such as waving the contralateral arm.

Treatment

a Levodopa

Since the 1960s when levodopa (L-dopa) benefits were first recognised,21 L-dopa has become the gold standard of PD therapy.22 There is a dichotomy as to whether one starts this early or waits. Many experts prefer to wait until the condition is fully apparent, arguing that L-dopa may have a finite period of possible effect after which the potency is diminished. This is contrary to personal view and is not the course personally adopted. The patient is referred because symptoms are affecting quality of life, which should improve with treatment. This translates into a personal choice to start therapy early after diagnosis.

L-dopa is provided either in combination with carbidopa or benserazide (Sinemet® or Madopar® respectively). Both carbidopa and benserazide are peripheral dopa decarboxylase inhibitors (DDI). They act by reducing the peripheral metabolism of L-dopa, which translates into more L-dopa crossing the blood–brain barrier (BBB). This, in turn, means that less L-dopa need be administered. L-dopa is used because dopamine does not cross the BBB and L-dopa is metabolised to dopamine after crossing it, replacing failing dopamine stores.

b Selegiline

The most supportive evidence favouring the use of Eldepryl® emerged from the DATATOP study23 that suggested Eldepryl® delayed disease progression, although it was less clear as to its direct symptomatic effects.

One of the reasons Eldepryl® fell out of favour was the 1995 United Kingdom report that identified increased mortality from the combination of Eldepryl® and Sinemet®.24 This has subsequently been criticised25,26 and ‘MIMS Annual’ states ‘No other clinical trial to date has shown an increase in mortality associated with the use of selegiline’.

c Dopamine agonists

Once the patient has shown progression on the combination of low dose L-dopa and selegiline (Sinemet® or Madopar®) in 100 : 25 combination one b.d. (maximum one t.d.s.) plus Eldepryl® 5 mg one b.d., personal preference advocates addition of low dose dopamine agonist to the cocktail. Previous personal preference was for cabergoline (Cabaser®), a long-acting ergoline-8-carbamoxide dopamine agonist. Such is the changing face of therapeutics that a whole different genre of dopamine agonists is currently available.

One must consider the role of dopamine agonists in the evolution of ‘punding’ and discontrol syndromes, such as compulsive gambling and impulsivity. Punding is a constellation of complex sterile and stereotyped behaviours, including absorption in use of technical equipment, almost obsessional behaviour (including handling, examining, sorting, grooming, hoarding, fidgeting while rearranging) and purposeless behaviour.19 While first noted in amphetamine and cocaine addicts in the 1970s, it was described with PD therapy in 1994.19 Excessive gambling and impulsivity are other considerations thought to be exacerbated by dopamine agonists, as is hypersexuality.

Other Medications

Should there be need for greater dopamine effect the use of amantadine (Symmetrel®), starting at a dosage of 100 mg per day and again titrating to efficacy, may offer additional gain. Psychiatric side-effects with Symmetrel® may limit its use.

Conclusion

This chapter has not discussed physical intervention with mobilisation training and rehabilitation with physiotherapy. This does not diminish their role but the focus is on pharmacological treatment. Having said that, the general practitioner is ideally placed to observe the patient and recommend mobilisation training as the condition progresses. The use of a walking stick or later a walking frame may greatly reduce the propensity to falls, as a consequence of ‘failed’ ‘righting reflexes’. The use of these aids is somewhat different to their use in painful situations, as their purpose is to spread the centre of gravity (rather than function as a splint). The addition of a walking aid in PD is to widen the area of stance, thereby enhancing stability. This is often a foreign concept for patients and hence requires training. This may dictate referral to an experienced physiotherapist, possibly within a rehabilitation service. These concepts are definitely the role of the general practitioner, who is best equipped to approach each individual patient’s needs and expectations. This confirms the ongoing need for a strong, working partnership between the general practitioner and consultant.

1 Parkinson J. An essay on the shaking palsy. London: Whittingham & Rowland; 1817.

2 Samci A, Nutt JG, Ransom BR. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2004;363:1783-1793.

3 Tanner CM, Goldman SM. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Neurol Clin. 1996;14(2):317-335.

4 Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427-442.

5 Silver D. Impact of functional age on the use of dopamine agonists in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurologist. 2006;12(4):214-223.

6 Nussbaum RL, Ellis CE. Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. New England J Medicine. 2003;348(14):1356-1364.

7 Baldwin CM, Keating GM. Rotigotine transdermal patch: a review of its use in the management of Parkinson’s disease. CNS Drugs. 2007;21(12):1039-1055.

8 Gelb D, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(1):33-39.

9 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical Guidelines 35: Parkinson’s disease. June. Online. Available http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG35, 2006. 29 Apr 2011

10 Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Peuralinna T, Dutra A, Nussbaum R, Lincoln S, Crawley A, Hanson M, Maraganore D, Adler C, Cookson MR, Muenter M, Baptista M, Miller D, Blancato J, Hardy J, Gwinn-Hardy K. alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2003;302(5646):841.

11 Wikipedia. Parkinson’s disease. Online. Available http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parkinson’s_disease, 2011. 29 Apr 2011

12 Shannon KM. Contemporary diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease. Pennsylvania: Handbooks in Health Care; 2007.

13 Langston JW, Ballard P. Parkinsonism induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP): implications for treatment and the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Can J Neurol Sci. 1984;11:160-165.

14 Thiruchelvam M, Richfield EK, Baggs RB, Tank AW, Cory-Slechta DA. The nigrostratal dopaminergic system as a preferential target of repeated exposures to combined paraquat and maneb: implications for Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci. 2000;20(24):9207-9214.

15 Betarbet R, Sherer TB, MacKenzie G, Garcia-Osuma M, Panov AV, Greenamyre JT. Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(12):1301-1306.

16 Quik M. Smoking, nicotine and Parkinson’s disease. Trends in Neuroscience. 2004;27(9):561-568.

17 Chan DKY, Woo J, Ho SC, Pang CP, Law LK, Ng PW, Hung WT, Kwok T, Hui E, Orr K, Leung MF. Genetic and environmental risk factors for Parkinson’s disease in a Chinese population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:781-784.

18 Chandhuri KR, Healy DG, Schapira AH. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:235-245.

19 O’Sullivan SS, Evans AH, Lees AJ. Punding in Parkinson’s disease. Pract Neurol. 2007;7:397-399.

20 Shannon KM. Contemporary diagnosis and management of Parkinson’s disease. Pennsylvania: Handbooks in Health Care; 2007. p. 146

21 Cotzias GC, van Woert MH, Schiffer LM. Aromatic amino acids and modification of Parkinsonism. New England J Medicine. 1967;276:374-379.

22 Stocchi F. The levodopa wearing-off phenomenon in Parkinson’s disease: pharmacokinetic considerations. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2006;7(10):1399-1407.

23 Shoulson I. DATATOP: a decade of neuroprotective inquiry. Parkinson Study Group. deprenyl and tocopherol antioxidative therapy of Parkinsonism. Ann Neurol. 1998;44(3 suppl. 1):S160-S166.

24 Lees AJ. Investigation by Parkinson’s Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom into comparison of therapeutic effects and mortality data of levodopa and levodopa combined with selegiline in patients with early, mild Parkinson’s disease. British Medical J. 1995;311:1602-1607.

25 Olanow CW, Fahn S, Langston JW, Godbold J. Selegiline and mortality in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;40:841-845.

26 Ben-Shlomo Y, Churchyard A, Head J, Hurwitz B, Overstall P, Ockelford J. Investigation by Parkinson’s Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom into excess mortality seen with combined levodopa and selegiline treatment in patients with early, mild Parkinson’s disease: further results of randomised trial and confidential inquiry. British Medical J. 1998;316:1191-1196.