Parenteral nutrition

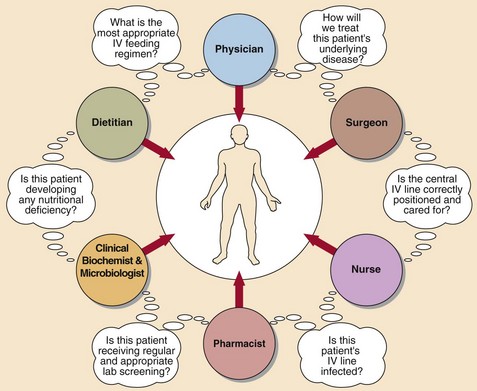

The provision of nutrients to the body’s cells is a highly complex physiological process involving many endocrine, exocrine and other metabolic functions. Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) completely bypasses the gastrointestinal tract, delivering processed nutrients directly into the venous blood. It is more physiological to feed patients enterally, and parenteral nutrition should only be considered once other possibilities have been deemed unsuitable. The institution of TPN is never an emergency and there should always be time for consultation and for baseline measurements to be performed. A team approach is best practice (Fig 54.1) and followed in most hospitals.

Route of administration

Components of TPN

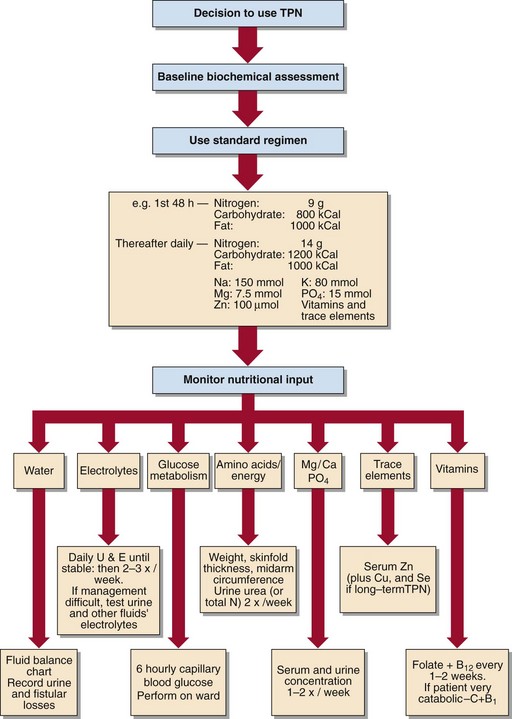

TPN should, as its name suggests, provide complete artificial nutrition. An appropriate volume of fluid will contain a source of calories, amino acids, vitamins and trace elements (Fig 54.2). The calorie source is a mixture of glucose and lipid. Many patients who receive TPN are given standard proprietary regimens and prepackaged solutions. These have made TPN much easier, but as with any such approach in medicine there are some patients who require more tailored regimens.

Monitoring patients on TPN

In addition to baseline assessment of patients receiving TPN, there should also be a strict policy for careful clinical and biochemical monitoring of these patients (Fig 54.3). This is especially important if the TPN is medium to long term. The tests described on pages 104–105 have particular relevance here.