Chapter 12 Paravertebral Block

The paravertebral space does not naturally exist. It is a potential space that can be created by fluid distention. If fluid (e.g., local anesthetics) is injected, it will distend and open a wedge-shaped space [1]. The boundaries of the paravertebral space are described in Table 12.1. Lumbar paravertebral block (PVB) is also known as lumbar plexus block and psoas compartment block.

Table 12.1 Boundaries of the Paravertebral Space

| Posterior | |

| Anterior | Parietal pleura |

| Medial | Posterolateral aspect of the vertebra, intervertebral disc, intervertebral foramen |

| Superior | Occiput |

| Inferior | Alar of the sacrum |

| Lateral | No limit; contiguous with the intercostal space |

From Richardson J. Paravertebral anesthesia and analgesia. Can J Anaesth 2004;51:R1-R6.

Local anesthetics injected in this area will bathe the following neurologic structures: the anterior and posterior rami of the spinal nerve, and the white and gray rami communicantes. In the thoracic region, the sympathetic chain is exposed to injectate because it is located laterally to the vertebral body, not anterolaterally as in the lumbar region. In the lumbar region, the sympathetic chain may not be involved because it is separated from more posterior structures arising from the intervertebral foramen by the iliopsoas muscle, which originates from the lateral vertebral bodies (Table 12.2; Figs. 10-10 and 10-11)[1–4]. The sacral spine cannot be subjected to PVB owing to the fusion of the transverse processes to form the lateral mass.

Table 12.2 Potential Tracking of Injectate from Deposition within the Paravertebral Space

| Superior and inferior | |

| Medial | Through the intervertebral foramen (epidural anesthesia) |

| Lateral | Contribution to cervical, stellate ganglion, brachial plexus, intercostal and lumbar plexus blockade |

| Anterior | Not possible unless pleura is breached |

From Richardson J. Paravertebral anesthesia and analgesia. Can J Anaesth 2004;51:R1-R6.

In a study of patients with chronic pain undergoing PVB with 15 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine, a mean somatic block of five dermatomes was accompanied by a mean sympathetic block of eight dermatomes, as evidenced by thermographic detection of ipsilateral skin warming[5]. Combinations of local anesthetics with adjuncts such as opiates and clonidine may also be very helpful in improving the quality and duration of the nerve block.

The dose of local anesthetics required involves a consideration of the number of dermatomes to block. Continuous infusion provides better analgesia than intermittent bolus doses[1,6].

Indications

The indications for paravertebral block vary with the location of the block [1–3,6–16].

Thoracic Paravertebral Block

Thoracic PVB is performed for the following indications (Box 12.1):

Unilateral surgical procedures, such as thoracotomy, breast surgery, cholecystectomy, cardiac surgery, and renal or ureteric surgery

Unilateral surgical procedures, such as thoracotomy, breast surgery, cholecystectomy, cardiac surgery, and renal or ureteric surgery For management of herpes zoster pain, post-mastectomy pain, post-thoracotomy pain, chronic abdominal pain, chronic inguinal pain, benign or malignant neuralgia, complex regional pain syndromes with a sympathetic component, vascular insufficiency, and differential nerve blockade

For management of herpes zoster pain, post-mastectomy pain, post-thoracotomy pain, chronic abdominal pain, chronic inguinal pain, benign or malignant neuralgia, complex regional pain syndromes with a sympathetic component, vascular insufficiency, and differential nerve blockadeBOX 12.1 Reported Indications for Thoracic Paravertebral Block

Adapted from Karmakar MK. Thoracic paravertebral block. Anesthesiology 2001;95:771-780.

As postoperative analgesia for:

As surgical anesthesia during:

For acute postherpetic neuralgia

As chronic pain management in benign and malignant neuralgia

Contraindications

Contraindications to lumbar or thoracic PVB may be classified as absolute and relative [1–3,12].

Absolute contraindications are as follows:

Relative contraindications to PVB are as follows:

A coagulation disorder or the use of anticoagulants; however, the neurologic consequences of a paravertebral hematoma are negligible

A coagulation disorder or the use of anticoagulants; however, the neurologic consequences of a paravertebral hematoma are negligible Empyema between the pleurae; the accompanying acidosis and hyperemia may cause systemic local anesthetics toxicity

Empyema between the pleurae; the accompanying acidosis and hyperemia may cause systemic local anesthetics toxicity Severe chest deformity or scoliosis, due to the possibility of injection into the meninges or pleura

Severe chest deformity or scoliosis, due to the possibility of injection into the meninges or pleuraA planned pleurectomy is not a contraindication to thoracic PVB.

Complications

The overall incidence of side effects or complications of thoracic or lumbar PVB is less than 5%; complications are as follows [1–3,17]:

Hypotension, which is unusual and has multifactorial causes; it usually involves the unmasking of relative hypovolemia by unilateral vasodilatation

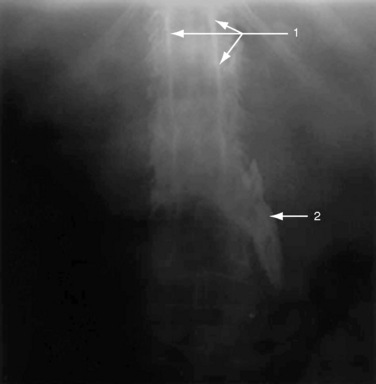

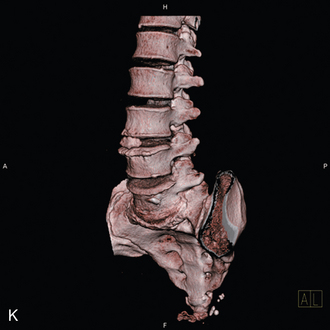

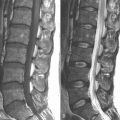

Hypotension, which is unusual and has multifactorial causes; it usually involves the unmasking of relative hypovolemia by unilateral vasodilatation Neurologic or hemodynamic events due to accidental epidural or intrathecal injection (Figs. 12-1 and 12-2)

Neurologic or hemodynamic events due to accidental epidural or intrathecal injection (Figs. 12-1 and 12-2)Procedures

Lumbar Paravertebral Block

Anatomy [16–25]

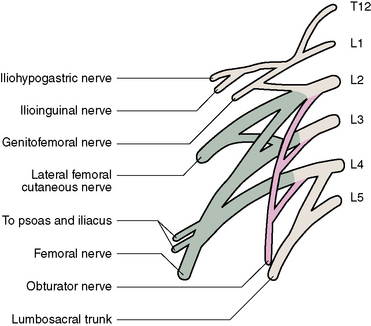

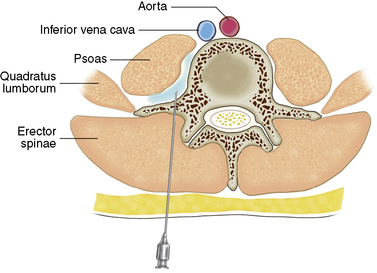

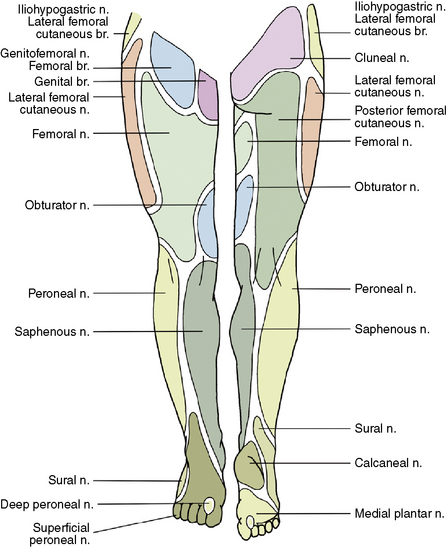

The lumbar plexus emanates from lumbar roots of L1 through L4 with a variable contribution from T12. It lies between the quadratus lumborum and psoas major muscles and descends vertically in the mass of the psoas muscle. At the level of L5 and S1, the nerve roots of L3 through L5 and even L2 run downward in a compact bundle before branching into the femoral and obturator nerves (Fig. 12-3).

The important nerves emanating from the lumbar plexus are the femoral nerve (posterior divisions of anterior primary rami of L2-L4), the obturator nerve (anterior divisions of the anterior primary rami of L2-L4), and the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (posterior divisions of the anterior rami of L2-L3). Other important nerves emanating from the lumbar plexus are the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, and genitofemoral nerves, which emanate primarily from L1 (Fig. 12-3).

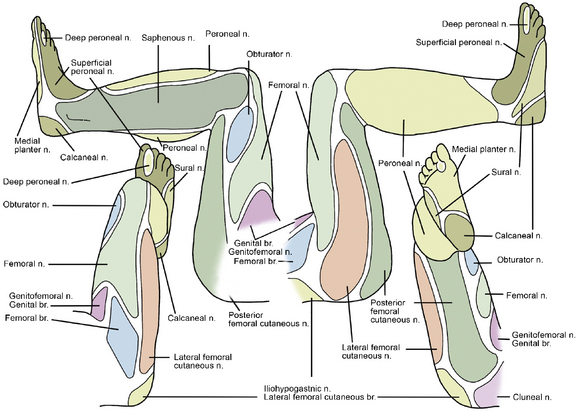

The femoral nerve is the largest terminal branch of the lumbar plexus. It provides the sensory innervation of the anterior aspect of the thigh and medial lower leg and the motor innervation of the quadriceps muscle (Figs. 12-4 and 12-5).

Figure 12–4 Somatic neurotomal distribution of the lower extremity. br., branch; n., nerve.

(Modified from Brown DL: Psoas compartment block. In: Atlas of Regional Anesthesia, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier/Saunders, 2006, pp 95-96.)

Figure 12–5 Somatic neurotomal distribution of the lower extremity. br., branch; n., nerve.

(Modified from Brown DL: Psoas compartment block. In: Atlas of Regional Anesthesia, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Elsevier/Saunders, 2006, pp 95-96.)

The obturator nerve supplies the obturator externus and the adductor muscles of the thigh and sends sensory fibers to the hip and knee joints. Sensory innervation of the obturator nerve to the skin is quite variable. Isolated block of the obturator nerve results in no cutaneous distribution in 57% of patients, an area of hypoesthesia in the superior part of popliteal fossa in 23%, and sensory deficit in the inferomedial aspect of the thigh in 20% [22]. However, adductor muscle weakness is a more reliable sign to evaluate obturator nerve block because all patients experience it (Figs. 12-4 and 12-5).

The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve provides sensory innervation of the lateral aspect of the thigh. The nerve divides into anterior and posterior branches. The anterior branch supplies cutaneous sensation to the lateral thigh, including just proximal to the patella. The posterior branch supplies the skin from the greater trochanter to the mid-thigh (Figs. 12-4 and 12-5).

Procedure

Single-injection technique

The procedure for the single-injection technique of lumbar PVB is as follows:

Continuous technique

Thoracic Paravertebral Block

Anatomy

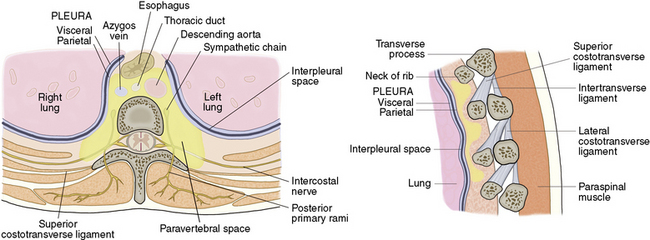

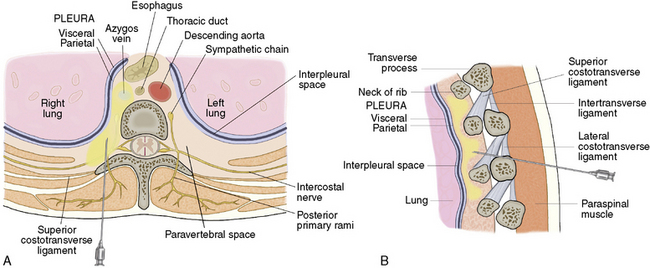

The paravertebral space is a wedge-shaped anatomical compartment adjacent to the vertebral bodies [1,2,4,12,14]. The space is defined anterolaterally by the parietal pleura, posteriorly by the costotransverse ligament, medially by the vertebra, vertebral disc, and intervertebral foramina, and superiorly and inferiorly by the head of the ribs (Fig. 12-9; Tables 12.1 and 12.2).

Within the space, the spinal root emerges from the intervertebral foramen and divides into dorsal and ventral rami. In addition, sympathetic fibers of the ventral rami enter the sympathetic trunk via the preganglionic white rami communicantes and the postganglionic gray rami communicantes in the space (Fig. 12-9).

Procedures

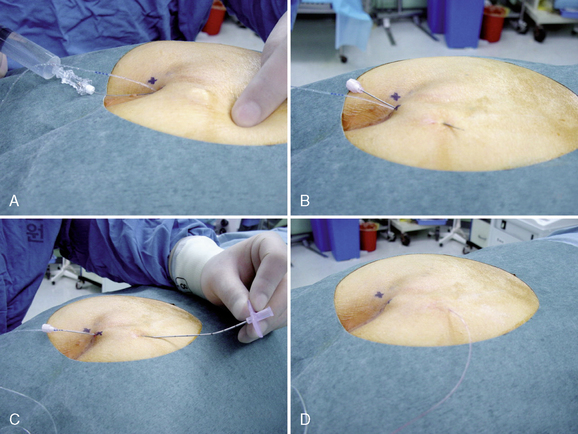

Single-injection technique

The procedure for the single-injection technique of thoracic PVB is as follows:

Continuous technique

Postprocedure care

No additional nursing skills or observations are necessary after lumbar or thoracic PBV, other than those required for the routine care of postoperative patients [5]. There is no need to watch specifically for cardiovascular changes. Mobilization should be encouraged. The analgesic regimen does not require admission to high-dependency care.

CASE STUDY 12.1

Procedure and Course

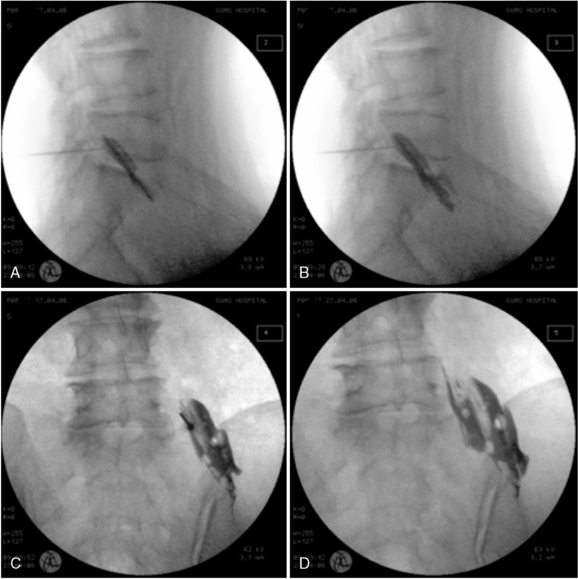

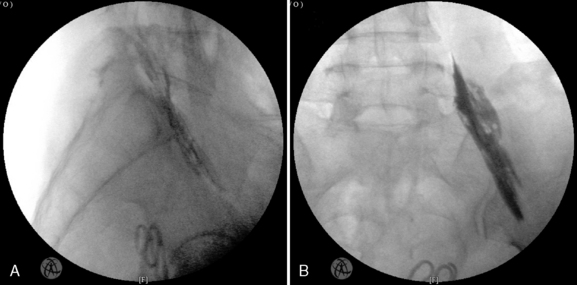

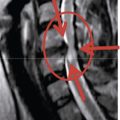

The patient was placed in the prone position. The double contour in the caudal end plate of L5 was eliminated, and the spinous process of the target vertebra was positioned in the midline. After sterile preparation and draping of the area, an 18-gauge Tuohy needle was advanced perpendicular to the skin and directed slightly toward the lower border of the transverse process of the target level under fluoroscopic guidance. The needle passed the inferior border of the transverse process of L5 and was advanced until loss of resistance to air was noted. To confirm needle placement in the paravertebral space, 2 mL of contrast agent was injected. After the paravertebral compartment had been identified and there was no epidural spread of dye (Fig. 12-13), 5 cm of the catheter was inserted into the space. The catheter was then subcutaneously tunneled 5 cm laterally. A bolus of 30 mL of 0.38% ropivacaine was administered via the catheter.

1 Greengrass R., Buckenmaier C.C.III. Paravertebral anaesthesia/analgesia for ambulatory surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2002;16:271-283.

2 Karmakar M.K. Thoracic paravertebral block. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:771-780.

3 Moreno M., Casalia A.G. Lumbar plexus anesthesia: Psoas compartment block. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2006;10:145-149.

4 Klein S.M., Nielsen K.C., Ahmed N., et al. In situ images of the thoracic paravertebral space. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:596-599.

5 Richardson J. Paravertebral anesthesia and analgesia. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:R1-R6.

6 Watson M.W., Mitra D., McLintock T.C., et al. Continuous versus single-injection lumbar plexus blocks: Comparison of the effects on morphine use and early recovery after total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:541-547.

7 Morin A.M., Kratz C.D., Eberhart L.H., et al. Postoperative analgesia and functional recovery after total-knee replacement: Comparison of a continuous posterior lumbar plexus (psoas compartment) block, a continuous femoral nerve block, and the combination of a continuous femoral and sciatic nerve block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:434-445.

8 Chelly J.E., Casati A., Al-Samsam T., et al. Continuous lumbar plexus block for acute postoperative pain management after open reduction and internal fixation of acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:362-367.

9 Chudinov A., Berkenstadt H., Salai M., et al. Continuous psoas compartment block for anesthesia and perioperative analgesia in patients with hip fractures. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1999;24:563-568.

10 Dadure C., Raux O., Gaudard P., et al. Continuous psoas compartment blocks after major orthopedic surgery in children: A prospective computed tomographic scan and clinical studies. Anesth Analg. 2004;98:623-628.

11 Wassef M.R., Randazzo T., Ward W. The paravertebral nerve root block for inguinal herniorrhaphy: A comparison with the field block approach. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:451-456.

12 Greengrass R.A. Posterior lumbar plexus block. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2003;7:3-7.

13 Pandin P.C., Vandesteene A., d’Hollander A.A. Lumbar plexus posterior approach: A catheter placement description using electrical nerve stimulation. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1428-1431.

14 Karmakar M.K., Chui P.T., Joynt G.M., et al. Thoracic paravertebral block for management of pain associated with multiple fractured ribs in patients with concomitant lumbar spinal trauma. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:169-173.

15 Eck J.B., Cantos-Gustafsson A., Ross A.K., et al. What’s new in pediatric paravertebral analgesia? Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2002;6:131-135.

16 Williams B.A., Spratt D., Kentor M.L. Continuous nerve blocks for outpatient knee surgery. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2004;8:76-84.

17 Litz R.J., Vicent O., Wiessner D., et al. Misplacement of a psoas compartment catheter in the subarachnoid space. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:60-64.

18 De Biasi P., Lupescu R., Burgun G., et al. Continuous lumbar plexus block: Use of radiography to determine catheter tip location. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28:135-139.

19 Sforsini C., Wikinski J.A. Anatomical review of the lumbosacral plexus and nerves of the lower extremity. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2006;10:138-144.

20 Awad I.T., Duggan E.M. Posterior lumbar plexus block: Anatomy, approaches, and techniques. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:143-149.

21 Moore D.C. Regional Block: A Handbook for Use in Clinical Practice of Medicine and Surgery, 4th ed., Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1965:276-277.

22 Brown D.L. Psoas compartment block. In Atlas of Regional Anesthesia, 3rd ed., Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders; 2006:95-96.

23 Kirchmair L., Entner T., Kapral S., et al. Ultrasound guidance for the psoas compartment block: An imaging study. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:706-710.

24 Bollini C.A., Sforsini C., Vascello L. Lumbar plexus block: Anterior approach. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2006;10:150-158.

25 Craven J. Lumbar and sacral plexuses. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2004;5:108.