CHAPTER 32 Paravertebral block

Clinical anatomy

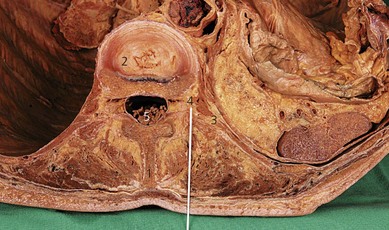

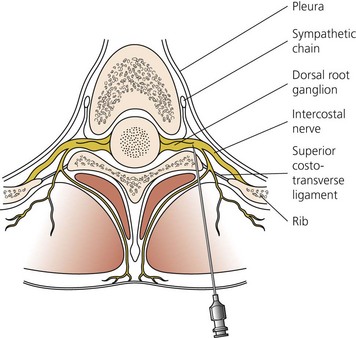

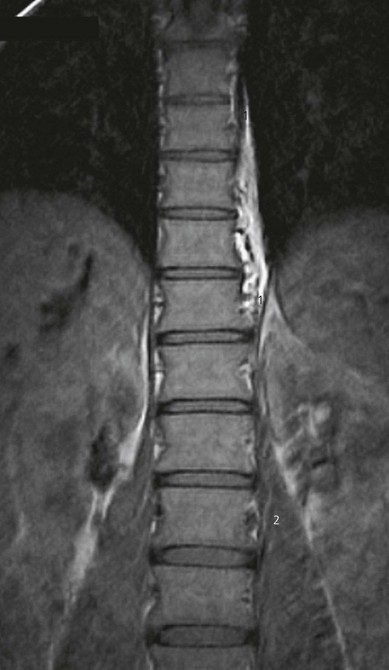

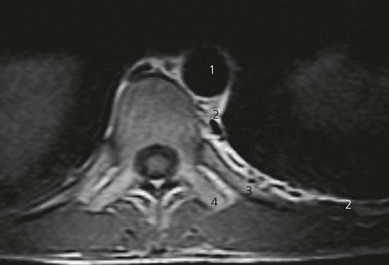

The paravertebral space is a wedge-shaped area on both sides of the vertebral column (Fig. 32.1). The boundaries of the space are: posteriorly, the superior costotransverse ligament; laterally, the posterior intercostal membrane; and anteriorly, the parietal pleura. At the base of the triangle (medially) is the posterolateral aspect of the vertebra, disc, and intervertebral foramen (Fig. 32.2). Contents of the paravertebral space include fatty tissue, intercostal vessels, spinal (intercostal) nerve, dorsal ramus, rami communicantes, and sympathetic chain (anteriorly). The paravertebral space is continuous medially with the epidural space and laterally with the intercostal space. The inferior limit of this space occurs at the origins of the psoas major muscle. The superior limit extends into the cervical region.

Surface anatomy

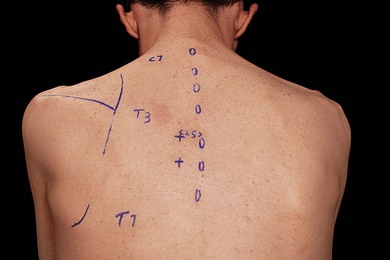

The main landmarks for the paravertebral block are the spinous and transverse processes. Identification of the appropriate vertebral level for blockade is facilitated by knowledge of dermatomes and anatomic landmarks that suggest vertebral level (Fig. 32.3). The spinous process of C7 (vertebrae prominens) is prominent and does not move with neck flexion. The spine and inferior angle of the scapula lie at the T3 and T7 vertebral levels, respectively.

Sonoanatomy

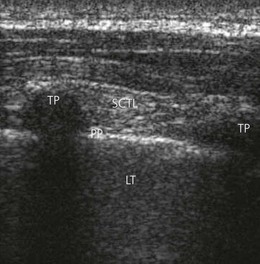

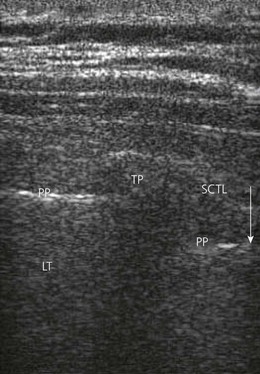

A linear array transducer is placed initially at a point 2.5 cm lateral to the tip of the spinous process in a vertical orientation, obtaining a sagittal paramedian view of the transverse processes (TP), superior costotransverse ligament (SCTL) and underlying pleura (Fig. 32.4). The transverse processes are seen as interrupted hyperechoic lines with loss of image beneath. The parietal pleura is identified as a bright structure running deep to the adjacent TPs and can be seen to slide with patient respirations. The superior costotransverse ligament, though less distinct, is seen as a collection of homogeneous linear echogenic bands alternating with echo-poor areas running from one TP to the next (Fig. 32.4).

Technique

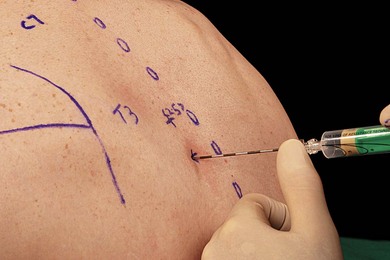

Landmark-based approach

The needle insertion point is infiltrated with local anesthetic using a 25-G needle. An 18-G Tuohy needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin until contact is made with the transverse process (Fig. 32.5). This usually occurs 2–4 cm from the skin. The location of the transverse process is critical in the performance of this block. If this contact is not made, it is likely that the needle lies between the transverse processes. The needle should be withdrawn and redirected in a caudal or cephalic direction (Fig. 32.6). Once the transverse process is identified, the needle is withdrawn and redirected in a cephalic/caudad direction to ‘walk’ over/under the transverse process.

Local anesthetic solution injected into the paravertebral space may remain localized, spread to the ipsilateral paravertebral spaces above and below the injection site (Fig. 32.7), pass laterally through the intercostal space (Fig. 32.8), or spread medially through the epidural space or across the vertebral bodies. Thermographic studies have demonstrated that 15 mL of bupivacaine 0.5% produces a somatic block of five dermatomes, and a sympathetic block over eight dermatomes. Little is known regarding the factors that influence spread.

Ultrasound-guided approach

Intravenous access, ECG, pulse oximetry and blood pressure monitoring are established. The block tray is set up as previously outlined. The ultrasound machine and block tray should be placed in positions which allow the operator to simultaneously scan the patient and take items from the block tray with minimal movement. This setup may take some forethought but is a worthwhile exercise, and will facilitate successful regional anesthesia. The operator stands on the side to be blocked, with the patient in the sitting position (Fig. 32.9). The relevant spinous processes are palpated and marked. A line is drawn 2.5 cm lateral to the spinous process. The needle insertion point is 2.5 cm lateral to the relevant spinous process.

The transverse processes are generally found at a depth of 2–3 cm from the skin. A sagittal image of the posterior chest wall is obtained and the transverse processes, superior costotransverse ligament and parietal pleura identified (Fig. 32.4). The midpoint of the transducer is aligned midway between the two adjacent TPs, local anesthesia is infiltrated at its lower border and an 18-G Tuohy needle introduced in a needle-in-plane approach in a cephalad orientation (Fig. 32.10). The paravertebral space is entered midway between the two TPs, avoiding bony contact. The tip of the needle is advanced under direct vision to puncture the superior costotransverse ligament. Saline (3 mL) is then injected deep to the SCTL to demonstrate the position of the injectate. Following a negative aspiration test, 15–20 mL of local anesthetic agent is injected and visualized filling the paravertebral space (Fig. 32.11).

An ultrasound-guided paravertebral technique has been described where the needle is advanced in-plane with the transducer, in a lateral-to-medial direction.1 An assisted technique may also be used where the relevant structures are identified and measurements are used to facilitate block performance.

Adverse effects

Clinical pearls

Davies RG, Myles PS, Graham JM. A comparison of the analgesic efficacy and side-effects of paravertebral vs epidural blockade for thoracotomy – a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(4):418-426.

Exadakatylos AK, Buggy DJ, Moriarty DC, et al. Can anesthetic technique for primary breast cancer surgery affect recurrence or metastasis? Anesthesiology. 2006;28:727-731.

Hara K, Sakura S, Nomura T, Saito Y. Ultrasound guided thoracic paravertebral block in breast surgery. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(2):223-225.

Karmakar MK. Thoracic paravertebral block. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:771-780.

Naja MZ, Gustafsson AC, Ziade MF, et al. Distance between the skin and the thoracic paravertebral space. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(7):680-684.

Naja Z, Lönnqvist PA. Somatic paravertebral blockade. Incidence of failed block and complications. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:1184-1188.

Pusch F, Wildling E, Klimscha W, Weinstabl C. Sonographic measurement of needle insertion depth in paravertebral blocks in women. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85(6):841-843.

Richardson J, Lönnqvist PA. Thoracic paravertebral block. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81:230-238.