Chapter 33 Parasitic infestations

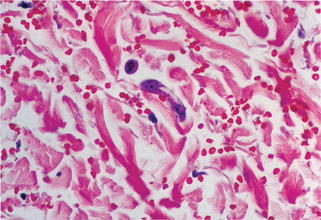

Figure 33-2. Larva currens. Biopsy demonstrates migrating larva of Strongyloides stercoralis in the dermis.

(Courtesy of the Fitzsimons Army Medical Center teaching files.)

Table 33-1. Parasitic Infestations of the Skin

| PARASITIC INFESTATION | VECTOR OR MODE OF TRANSMISSION |

|---|---|

| Filariasis | Mosquito |

| Onchocerciasis | Black fly |

| Creeping eruption | Soil contact and larval penetration |

| African trypanosomiasis | Tsetse fly |

| American trypanosomiasis | Kissing bug |

| Leishmaniasis | Sand fly |

| Schistosomiasis | Water contact and cercarial penetration |

| Dracunculiasis, sparganosis | Ingestion of larva |

| Echinococcosis, cysticercosis | Ingestion of cysts |

| Amebiasis | Direct contact or ingestion of cysts |

| Loiasis | Horse and deer flies |

| Demodex | Person-to-person contact in childhood |

Figure 33-4. Marked scrotal enlargement in elephantiasis.

(From Zaiman H, Jong EC: Parasitic diseases of the skin and soft tissue. In Stevens DL, editor: Atlas of infectious diseases, vol II, New York, 1995, Churchill Livingstone.)

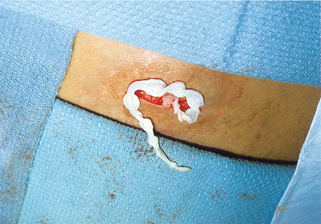

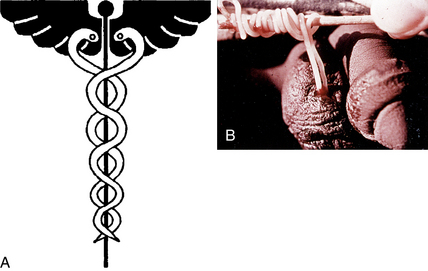

Figure 33-5. A, Caduceus. B, The classic matchstick recovery technique used in extracting the adult female worm.

(From Zaiman H, Jong EC: Parasitic diseases of the skin and soft tissue. In Stevens DL, editor: Atlas of infectious diseases, vol. II, New York, 1995, Churchill Livingstone.)

| SPECIES | DISEASE | DISTRIBUTION |

|---|---|---|

| L. donovani group | Visceral leishmaniasis, kala-azar | India, Asia, Middle East, Africa |

| L. tropica group | Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis, oriental sore, newly discovered viscerotropic disease | India, Middle East |

| L. viannia group (L. braziliensis group) | New World mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, espundia | Latin America |

| L. mexicana group | American cutaneous leishmaniasis | Mexico, Central America, Texas, South America |

Key Points: Parasitic Infestations

Centers for Disease Control (CDC): Unexplained dermopathy: http://www.cdc.gov/unexplaineddermopathy/. Accessed July 25, 2010.