17

Paraoesophageal hernia and gastric volvulus

Introduction

Paraoesophageal hiatal hernia is a relatively rare condition comprising approximately 15% of hiatal hernias. This condition was first identified on post-mortem examination in 1903,1 and on upper gastrointestinal contrast radiography by Akerlund et al. in 1926.2 Since that time, the importance of these hernias has been recognised because of the resulting life-threatening complications including gastrointestinal bleeding, iron deficiency anaemia, gastric volvulus with subsequent strangulation and perforation.3 Management of paraoesophageal hernias has changed considerably since the development of laparoscopic repair and several areas of controversy remain as this technique continues to evolve.

Epidemiology

Hiatal hernias occur in approximately 10% of the population, with approximately 15% of these being paraoesophageal hernias.4 Risk factors for hiatal hernias include age greater than 50, body mass index greater than 25 kg/m2 and male gender.5 There is also a familial occurrence that confers a 20-fold increased risk in younger siblings of children with a hiatal hernia.6

Anatomy and natural history

The oesophagus enters the abdomen via the oesophageal hiatus of the diaphragm, which is comprised of the limbs of the right diaphragmatic crus,7 although varying degrees of contribution of the left crus are often present. Although not anatomically correct, descriptions of hiatal dissection and repair, including those presented here, typically refer to these limbs as the right and left diaphragmatic crura or pillars. The intra-abdominal oesophagus is anchored to the diaphragm by the phreno-oesophageal ligament, which maintains the position of the squamocolumnar junction within or slightly distal to the diaphragmatic hiatus and prevents displacement of the stomach through the diaphragm.8

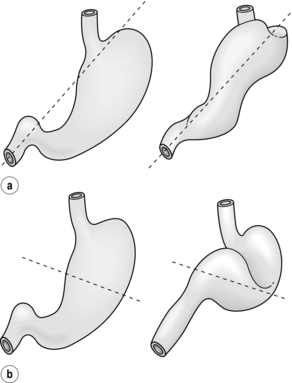

Derangements in the normal anatomy of the gastro-oesophageal junction and oesophageal hiatus allow herniation of the stomach through this opening into the thoracic cavity. The aetiology of these hernias is often unclear. Hiatal hernias are rare in Asian and African populations, and are more common in conditions of increased intra-abdominal pressure, such as obesity and pregnancy. Hiatal hernias are classified as types I–IV, with types II–IV representing forms of paraoesophageal hernia (Fig. 17.1). This nomenclature is slightly confusing, as giant hiatal hernias may appear to be a sliding or paraoesophageal hiatal hernia depending on the patient position. We prefer to use the term ‘giant hiatal hernias’ for the large hernias that are usually classified as type III and IV paraoesophageal hernia.

Figure 17.1 Classification of hiatal hernias. (a) Type I (sliding). (b) Type II (true paraoesophageal). (c) Type III (combined).

Most hiatal hernias (90%) are type I, or sliding, hernias in which the gastric cardia herniates upwards with proximal migration of the lower oesophageal sphincter into the thorax. The phreno-oesophageal ligament is attenuated, but remains intact.9 The term ‘sliding hiatal hernia’ is applied here because the gastric wall comprises a portion of the hernia sac, analogous to retroperitoneal structures in sliding inguinal hernias.

Type III (combined) hiatal hernias involve elements of both type I and II hernias, and represent the majority of paraoesophageal hernias presenting for surgical repair. These hernias result from enlargement of a type I hernia defect, to allow cephalad migration of the stomach in response to the transdiaphragmatic pressure gradient. There is a true hernia sac present with fundic herniation and proximal migration of the gastro-oesophageal junction into the thorax. This type of hernia is associated with laxity of the elements that retain normal gastric position, and the natural history is to progress to complete gastric herniation, with the appearance of an upside-down intrathoracic stomach on contrast radiography.10 This increased gastric mobility predisposes patients to gastric volvulus, which we will address in detail later in this chapter.

As with all hernias, the natural history of paraoesophageal hernia is progressive enlargement over time. Early in their course some are clinically silent, but most people have gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms, which may have been treated with medical therapy or not at all. By the time the hernia grows large enough to allow a paraoesophageal hernia of the stomach, a cardio-oesophageal angle is often recreated, which may cause reflux symptoms to wane as the paraoesophageal herniation recreates a more competent antireflux valve.11 The term ‘giant paraoesophageal hiatal hernia’ refers to defects in which at least half of the stomach is located within the thorax on contrast radiography, the hernia measures at least 6 cm in length on preoperative endoscopy, or a distance between the crura of at least 5 cm is noted on intraoperative inspection.12,13 These hernias are repaired using the same principles required for all paraoesophageal hernias, but the large hernia sac and propensity for oesophageal shortening make these cases especially challenging.

Presentation and diagnosis

Approximately half of all paraoesophageal hernias are clinically silent and become apparent on imaging studies obtained for another reason. Symptomatic hernias may present with epigastric or chest pain, heartburn, postprandial fullness, regurgitation or dysphagia. Many of the signs and symptoms are non-specific and may mimic those of acute myocardial infarction, gastric ulcer or pneumonia. Type II hernias typically present without reflux symptoms, whereas type III hernias most typically present with postprandial chest pain with or without reflux symptoms (e.g. heartburn, dysphagia, regurgitation). Others present with iron deficiency anaemia secondary to chronic blood loss from erosions of the gastric mucosa caused by repeated movement across the hiatus, a phenomenon originally described by Collis in 1961,14 or from an ulcer at the level of the diaphragm, described by Cameron from the Mayo Clinic.15,16

Operative indications

It has been generally accepted that reasonable surgical candidates should undergo repair regardless of symptoms. This recommendation is based on early series that showed an increased mortality after emergency surgery of 30% compared to 1% in elective cases. In 1967, Skinner and Belsey found that 6 of 21 patients with a known diagnosis of paraoesophageal hernia died from complications of their hernia when followed conservatively for 5 years.12

More recent studies have suggested differences in both the natural history of the disease and operative outcomes. Allen et al. followed 23 patients who refused operative repair of paraoesophageal hernias for a median follow-up of 78 months without development of any life-threatening complications.17 Others have advocated that asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic paraoesophageal hernias may be managed by a strategy of ‘watchful waiting’, with emergency surgery required in only 1.2% of cases and an operative mortality of 5.4% in this setting.18

Operative approaches

Principles of paraoesophageal hernia repair

The repair of paraoesophageal hernias may be approached via thoracotomy, laparotomy or laparoscopy. The principles of proper surgical repair are the same with each approach:19–21

Laparoscopic repair

Since its introduction by Cuschieri et al. in 1992,22 laparoscopic paraoesophageal hernia repair has gained popularity and proven to be feasible, safe and effective.23–30 Laparoscopy provides an attractive option because it combines some of the advantages of both thoracotomy (access to the hiatus and ability to perform extensive mobilisation of the oesophagus under direct vision) and laparotomy (lower morbidity and no need for single-lung ventilation or postoperative chest tube). Further, this minimally invasive approach may be better suited for the elderly patients in whom this disease most commonly occurs. This is a technically challenging operation that requires advanced laparoscopic skills, but when performed properly, carries a recurrence rate similar to the open approach.31

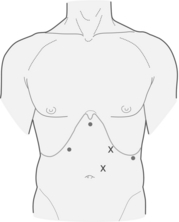

Set-up and port placement

A total of five trocars are used (Fig. 17.2). Peritoneal access is gained using a Veress needle, and an 11-mm trocar is placed just left of the midline, 15 cm caudal to the xyphoid process. Two ports are placed in the left subcostal position, a 12-mm trocar 12 cm lateral to the xyphoid process, and a 5-mm trocar 8 cm further to the left. Finally, two 5-mm ports are placed along the right costal margin, one in the subxyphoid position and the second approximately 10 cm lateral. A Nathenson liver retractor is used to retract the left lobe of the liver and expose the oesophageal hiatus.

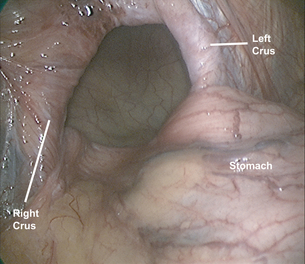

Reduction of hernia sac and fundic mobilisation

The stomach is gently reduced from the hernia sac (Fig. 17.3) and the left diaphragmatic pillar is identified. The dissection is carried out along the left crus between the endothoracic fascia and the hernia sac. After the anterior phreno-oesophageal membrane is divided using ultrasonic dissection, the stomach is retracted to the left to expose the right crus. The pars flaccida of the lesser omentum is divided and the dissection continues along the right crus to the decussation of the crura. The gastrosplenic omentum is then divided using ultrasonic dissection, and the short gastric vessels are divided all the way up to the cephalad extent of the stomach. Division of the posterior gastric attachments creates a retro- oesophageal window through which a Penrose drain is passed around the oesophagus to allow caudal retraction on the oesophagus and create exposure for the mediastinal dissection. Dissection proceeds from right to left, and the sac is opened to reveal a plane between the peritoneal sac and the mediastinum. Careful blunt and ultrasonic dissection develops this plane, with care taken to identify and preserve the vagal trunks and the peritoneal coverage of the crura, which aids in a second crural closure. With gentle retraction, the sac can be slowly mobilised out of the mediastinum and reduced into the abdominal cavity. Most surgeons excise and remove the hernia sac, but excessive fastidiousness in this exercise risks injury to the vagi as they course in close apposition to the hernia sac in the epiphrenic fat. We usually remove the majority of the sac, including all sac and epiphrenic fat on the left side of the oesophagus, well away from the vagal trunks and the end branches of the left gastric artery.

Assessment of oesophageal length

When the hernia sac is completely reduced from the mediastinum, it is imperative to have at least 2.5 cm of tension-free intra-abdominal oesophageal length. If a shortened oesophagus is identified an extensive circumferential mobilisation of the intrathoracic oesophagus is performed, which usually provides the desired oesophageal length. True shortened oesophagus is rare but a wedge gastroplasty can be performed over a 48 French bougie. A point is marked 3 cm below the angle of His, and a transverse staple line is created with two or three applications of a linear endoscopic stapler inserted via the left upper quadrant trocar. When the oesophageal dilator is reached, a vertical staple line created along the bougie creates a 3–4 cm neo-oesophagus, and the gastric wedge is removed from the abdomen.32

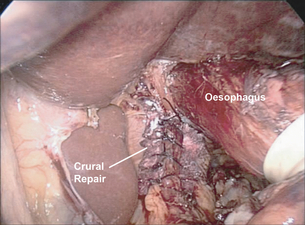

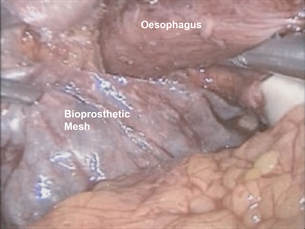

Crural dissection and repair

After complete reduction of the hernia sac and identification of an adequate length of intra-abdominal oesophagus, attention is turned to the crural closure. This is performed using interrupted, pledgeted, braided non-absorbable suture such as 0 silk (Fig. 17.4). It is frequently beneficial to reduce pneumoperitoneum pressure to 7 cm to close large diaphragmatic defects that are held open by the pneumoperitoneum. Once closed, the adequacy of closure may be tested by the passage of a 56–60 French Maloney dilator, which should completely fill the new hiatal aperture. If the diaphragmatic repair appears to be ‘pinching’ the oesophagus with the dilator in place, a suture is removed. Conversely, if the closure is loose, the dilator is withdrawn into the upper oesophagus and another suture is added. In addition to suture repair, we have advocated the use of biological mesh for reinforcement of the crural repair. A 3 cm × 5 cm U-shaped piece of bioprosthetic mesh is fixed in place overlying the repair. Rather than struggle with difficult suture angles, or risking an intrathoracic injury by using hernia tacks to hold the mesh in place, we ‘glue’ the mesh to the diaphragm with tissue sealant (Fig. 17.5).

Fundoplication

After the completion of the crural repair, we routinely perform an antireflux procedure because failure to do so has been associated with a 20–40% rate of postoperative reflux and preoperative testing cannot successfully predict postoperative reflux.33–37 A Nissen fundoplication is performed unless the patient has a known history of severe oesophageal dysmotility, necessitating a partial fundoplication. A floppy Nissen is performed by passing the fundus of the stomach behind the oesophagus. When a wedge gastroplasty is performed, the staple line is apposed to the stomach wall and the most cephalad stitch of the fundoplication is placed on the true oesophagus above the neo-oesophagus, ensuring that no gastric mucosa lies above the wrap. The fundoplication is created using three 2/0 silk or braided nylon sutures incorporating the stomach and oesophagus with each ‘bite’. An additional suture may be placed from the posterior portion of the wrap to the oesophagus.

Current controversies in paraoesophageal hernia management

Recurrence rate

As with any hernia repair, recurrence is a well-known complication of paraoesophageal hernia surgery. Early studies demonstrated a higher rate of recurrence in the laparoscopic approach as compared to the open approach,26 but after the introduction of mesh crural reinforcement and oesophageal lengthening when indicated, the rate of recurrence for laparoscopic paraoesophageal hernia repair decreased31 and is now considered to be equivalent to open repair.

Oesophageal lengthening procedures

Most surgeons today agree that oesophageal shortening can result from oesophageal inflammation in the setting of proximal migration of the gastro-oesophageal junction. This results in tension on the hiatal repair, which has been implicated in up to 33% of surgical failures after open and laparoscopic repairs.38–41

Short oesophagus has been recognised and studied for several decades, with the Collis gastroplasty described for its treatment in 1957.40 Although preoperative testing can show the position of the gastro-oesophageal junction and suggest the presence of shortened oesophagus, these tests cannot reliably predict difficulty reducing the stomach to its anatomical position without tension intraoperatively.42 Currently, shortened oesophagus is defined as the inability to gain 2.5–3 cm of tension-free intra-abdominal oesophagus following mediastinal dissection.

Oesophageal tension due to shortened length favours hernia recurrence by cephalad migration of the fundoplication through the crural repair. Ten per cent of paraoesophageal hernia repairs require a lengthening procedure and their use is mandatory in cases when adequate tension-free oesophageal length cannot be obtained from mediastinal dissection alone. The wedge gastroplasty and fundoplication has demonstrated improved resolution of symptoms as compared to fundoplication alone in the repair of type II–IV hernias, while maintaining no difference in hospital length of stay or overall quality of life.43

Prosthetic crural reinforcement

Two prospective randomised trials have evaluated synthetic mesh reinforcement. One showed a decreased recurrence rate with polytetrafluoroethylene reinforcement of the crural repair44 and another showed similar results with prolene mesh reinforcement of the hiatus.45 However, movement of the mesh along the oesophagus with each respiration can cause serious and significant complications such as mesh erosion, ulceration, stricture and dysphagia.46–49 Occasionally, these complications can be so severe as to necessitate oesophagectomy or gastrectomy,49 and as a result the use of synthetic mesh has fallen out of favour and should be avoided.

Two studies have evaluated the rate of recurrence after repair with bioprosthetic mesh in a multicentre, prospective, randomised fashion. The first, published in 2006, showed a significant reduction in early recurrence following bioprosthetic mesh repair, without increased dysphagia or impaired quality of life compared to those with primary crural repair.50 This study was limited by rather short-term follow-up of only 6 months, so a second study was performed of the same patient population at 5-year follow-up.51 By 5 years, there was no difference in recurrence rate by either upper GI swallow study or symptoms, and there were no complications related to the mesh. Accordingly, bioprosthetic mesh reinforcement appears to be safe, but it may not change the long-term rate of recurrence. No study to date has prospectively compared the numerous types of bioprosthetic mesh in paraoesophageal hernia repair.

Acute gastric volvulus

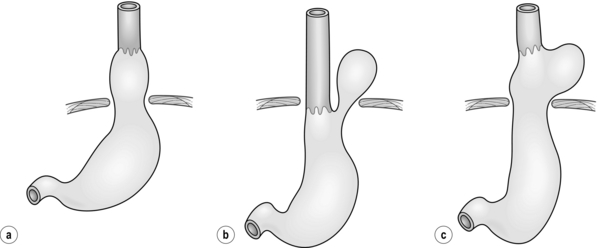

Gastric volvulus, first described by Berti in 1896,52 is the rotation of the stomach more than 180° around a fixed axis of rotation. Gastric strangulation from acute gastric volvulus is a dreaded complication of paraoesophageal hernia and it remains the driving force for recommending elective repair of asymptomatic hernias. Gastric strangulation occurs in up to 28% of cases of acute gastric volvulus,53 and may progress to gastric necrosis, perforation and severe sepsis leading to cardiovascular collapse if it is not diagnosed quickly and managed aggressively.

Frequency and mechanism

The anatomical classification of gastric volvulus is based on the axis of rotation (Fig. 17.6). Organoaxial volvulus is the most common type, and it accounts for almost all cases of acute gastric volvulus. This involves rotation of the stomach around the anatomical (longitudinal) axis, represented as a line drawn from the cardia to the pylorus,10 frequently resulting in gastric strangulation. In mesoentericoaxial volvulus, the antrum of the stomach rotates anteriorly and superiorly around a transverse axis that extends from the mid-lesser curvature to the mid-greater curvature.10 The rotation is typically incomplete and results in intermittent gastric obstruction, rather than acute strangulation.

Presentation and diagnosis

Acute gastric volvulus typically presents with a history of dysphagia and high gastric obstruction. In 1904, Borchardt described the classic symptom triad of severe epigastric pain, retching and inability to vomit, and inability to pass a nasogastric tube.54 Patients may also present with severe chest pain and minimal abdominal findings as the incarcerated segment is often located within the chest.53

References

1. Andrew, L. The height of the diaphragm in relation to the position of certain abdominal viscera. Lancet. 1903; 1:790.

2. Akerlund, A., Onnell, H., Key, E. Hernia diaphragmatica hiatus oesophagei vom anatomischen und rontgenologischen gesichtspunct. Acta Radiol. 1926; 6:3–22.

3. Ellis, F.H., Jr., Crozier, R.E., Shea, J.A., Paraesophageal hiatus hernia. Arch Surg. 1986;121(4):416–420. 3954587

4. Hill, L.D., Tobias, J.A., Paraesophageal hernia. Arch Surg. 1968;96(5):735–744. 5647546

5. Menon, S., Trugdill, N., Risk factors in the aetiology of hiatus hernia: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 23:133–138. 21178776

6. Carre, I.J., Johnston, B.T., Thomas, P.S., et al, Familial hiatal hernia in a large five generation family confirming true autosomal dominant inheritance. Gut. 1999;45(5):649–652. 10517898

7. Marchand, P., The anatomy of esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm and the pathogenesis of hiatus herniation. J Thorac Surg. 1959;37(1):81–92. 13621476

8. Kahrilas, P.J., Wu, S., Lin, S., et al, Attenuation of esophageal shortening during peristalsis with hiatus hernia. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(6):1818–1825. 7498646

9. Skinner D.B., Roth J.L.A., Sullivan B.H., eds. Gastroenterology, 4th ed., Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1985.

10. Kahrilas P.J., Speiss A.E., eds. The Esophagus, 3rd ed., Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

11. Wo, J.M., Branum, G.D., Hunter, J.G., et al, Clinical features of type III (mixed) paraesophageal hernia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(5):914–916. 8633580

12. Skinner, D.B., Belsey, R.H., Surgical management of esophageal reflux and hiatus hernia. Long-term results with 1,030 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1967;53(1):33–54. 5333620

13. Treacy, P.J., Jamieson, C.G., An approach to the management of paraesophageal hiatus hernias. Aust N Z J Surg 1987; 57:813–817. 3439921

14. Collis, J.L., A review of surgical results in hiatus hernia. Thorax 1961; 16:114–119. 13694777

15. Cameron, A.J., Incidence of iron deficiency anemia in patients with large diaphragmatic hernia. A controlled study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1976;51(12):767–769. 1086935

16. Cameron, A.J., Higgins, J.A., Linear gastric erosion A lesion associated with large diaphragmatic hernia and chronic blood loss anemia. Gastroenterology. 1986;91(2):338–342. 3487479

17. Allen, M.S., Trastek, V.F., Deschamps, C., et al, Intrathoracic stomach. Presentation and results of operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105(2):253–259. 8429652

18. Stylopoulos, N., Gazelle, G.S., Rattner, D.W., Paraesophageal hernias: operation or observation? Ann Surg. 2002;236(4):492–501. 12368678

19. Edye, M., Salky, B., Posner, A., et al, Sac excision is essential to adequate laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc. 1998;12(10):1259–1263. 9745068

20. Patel, H.J., Tan, B.B., Yee, J., et al, A 25-year experience with open primary transthoracic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127(3):843–849. 15001915

21. Watson, D.I., Davies, N., Devitt, P.G., et al, Importance of dissection of the hernial sac in laparoscopic surgery for large hiatal hernias. Arch Surg. 1999;134(10):1069–1073. 10522848

22. Cuschieri, A., Shimi, S., Nathanson, L.K., Laparoscopic reduction, crural repair, and fundoplication of large hiatal hernia. Am J Surg. 1992;163(4):425–430. 1532701

23. Diaz, S., Brunt, L.M., Klingensmith, M.E., et al, Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair, a challenging operation: medium-term outcome of 116 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7(1):59–67. 12559186

24. Edye, M.B., Canin-Endres, J., Gattorno, F., et al, Durability of laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Ann Surg. 1998;228(4):528–535. 9790342

25. Gantert, W.A., Patti, M.G., Arcerito, M., et al, Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernias. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186(4):428–433. 9544957

26. Hashemi, M., Peters, J.H., DeMeester, T.R., et al, Laparoscopic repair of large type III hiatal hernia: objective follow-up reveals high recurrence rate. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190(5):553–561. 10801022

27. Horgan, S., Eubanks, T.R., Jacobsen, G., et al, Repair of paraesophageal hernias. Am J Surg. 1999;177(5):354–358. 10365868

28. Mattar, S.G., Bowers, S.P., Galloway, K.D., et al, Long-term outcome of laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(5):745–749. 11997814

29. Schauer, P.R., Ikramuddin, S., McLaughlin, R.H., et al, Comparison of laparoscopic versus open repair of paraesophageal hernia. Am J Surg. 1998;176(6):659–665. 9926809

30. Wiechmann, R.J., Ferguson, M.K., Naunheim, K.S., et al, Laparoscopic management of giant paraesophageal herniation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(4):1080–1087. 11308140

31. Zehetner, J., Demeester, S.R., Ayazi, S., et al, Laparoscopic versus open repair of paraesophageal hernia: the second decade. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(5):813–820. 21435915

32. Terry, M.L., Vernon, A., Hunter, J.G., Stapled-wedge Collis gastroplasty for the shortened esophagus. Am J Surg. 2004;188(2):195–199. 15249252

33. Behrns, K.E., Schlinkert, R.T., Laparoscopic management of paraesophageal hernia: early results. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1996;6(5):311–317. 8897241

34. Trus, T.L., Bax, T., Richardson, W.S., et al, Complications of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1(3):221–228. 9834351

35. Casabella, F., Sinanan, M., Horgan, S., et al, Systematic use of gastric fundoplication in laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernias. Am J Surg. 1996;171(5):485–489. 8651391

36. Lal, D.R., Pellegrini, C.A., Oelschlager, B.K., Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85(1):105–118. 15619532

37. Swanstrom, L.L., Jobe, B.A., Kinzie, L.R., et al, Esophageal motility and outcomes following laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair and fundoplication. Am J Surg. 1999;177(5):359–363. 10365869

38. DePaula, A.L., Hashiba, K., Bafutto, M., et al, Laparoscopic reoperations after failed and complicated antireflux operations. Surg Endosc. 1995;9(6):681–686. 7482163

39. Ellis, F.H., Jr., Gibb, S.P., Heatley, G.J., Reoperation after failed antireflex surgery. Review of 101 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1996;10(4):225–232. 8740056

40. Collis, J.L., An operation for hiatus hernia with short oesophagus. Thorax. 1957;12(3):181–188. 13467876

41. Jobe, B.A., Horvath, K.D., Swanstrom, L.L., Postoperative function following laparoscopic Collis gastroplasty for shortened esophagus. Arch Surg. 1998;133(8):867–874. 9711961

42. Gastal, O.L., Hagen, J.A., Peters, J.H., et al, Short esophagus: analysis of predictors and clinical implications. Arch Surg. 1999;134(6):633–638. 10367873

43. Nason, K.S., Luketich, J.D., Awais, O., et al, Quality of life after Collis gastroplasty for short esophagus in patients with paraesophageal hernia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(5):1854–1861. 21944737

44. Frantzides, C.T., Madan, A.K., Carlson, M.A., et al, A prospective, randomized trial of laparoscopic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) patch repair vs simple cruroplasty for large hiatal hernia. Arch Surg. 2002;137(6):649–652. 12049534

45. Kamolz, T., Granderath, F.A., Bammer, T., et al, Dysphagia and quality of life after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication in patients with and without prosthetic reinforcement of the hiatal crura. Surg Endosc. 2002;16(4):572–577. 11972190

46. Granderath, F.A., Kamolz, T., Schweiger, U.M., et al, Impact of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with prosthetic hiatal closure on esophageal body motility: results of a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2006;141(7):625–632. 16847231

47. Paul, M.G., DeRosa, R.P., Petrucci, P.E., et al, Laparoscopic tension-free repair of large paraesophageal hernias. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(3):303–307. 9079617

48. Tatum, R.P., Shalhub, S., Oelschlager, B.K., et al, Complications of PTFE mesh at the diaphragmatic hiatus. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(5):953–957. 17882502

49. Stadlhuber, R.J., Sherif, A.E., Mittal, S.K., et al, Mesh complications after prosthetic reinforcement of hiatal closure: a 28-case series. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(6):1219–1226. 19067074

50. Oelschlager, B.K., Pellegrini, C.A., Hunter, J., et al, Biologic prosthesis reduces recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2006;244(4):481–490. 16998356

51. Oelschlager, B.K., Pellegrini, C.A., Hunter, J.G., et al, Biologic prosthesis to prevent recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: long-term follow-up from a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg 2011; 213:461–468. 21715189

52. Berti, A. Singulare attortigliamento dele’esofago col duodeno seguita da rapida morte. Gazz Med Ital. 1896; 9:139.

53. Carter, R., Brewer, L.A., 3rd., Hinshaw, D.B., Acute gastric volvulus. A study of 25 cases. Am J Surg. 1980;140(1):99–106. 7396092

54. Borchardt, M. Aus Pathologie und therapie des magenvolvulus. Arch Klin Chir. 1904; 74:243.