CHAPTER 5 Paraesophageal hernia

Step 1. Clinical anatomy

♦ The main topic of this chapter is the operative management of paraesophageal hernias, which can also be referred to as giant hiatal hernias. These are usually managed by a surgeon and often require operative repair.

♦ Paraesophageal hernias (PEHs) are characterized by the migration of the gastroesophageal junction and the upper stomach into the mediastinum.

♦ There is typically a large anterior hernia sac that is composed of the attenuated phrenoesophageal ligament and two smaller posterior sacs. The sac is bordered by the mediastinal pleura, pericardium, and the aorta.

♦ The configuration of the stomach within the sac of a PEH may also be described in terms of its rotation, if present, in the organoaxial or mesioaxial position.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

♦ Patients often experience symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation because of the intrathoracic location of the gastroesophageal (GE) junction.

♦ Other frequently present symptoms include dysphagia, chest pain, and respiratory compromise, which are due to the mechanical effects of the herniated stomach in the mediastinum.

♦ The lining of the herniated stomach can develop deep ulcerations known as Cameron’s ulcers, which may cause occult blood loss. Some patients may not have any gastrointestinal symptoms but suffer only from chronic anemia. It is not rare for the diagnosis of PEH to be made in the workup for iron deficiency anemia.

♦ Occasionally, one encounters a patient with a PEH who is truly asymptomatic. The classic teaching has been that these patients should undergo repair to avoid the chance of strangulation. Because of the rarity of this event, combined with the known risks associated with elective repair, most patients can be managed with watchful waiting.

♦ Most patients with PEH are intermittently symptomatic. These patients should undergo elective repair by a laparoscopic approach if there is no contraindication.

♦ In the rare event of strangulation of the herniated stomach, chest pain and foregut obstruction are the usual associated presenting signs. Treatment of this condition requires vigorous resuscitation and urgent laparotomy. Partial gastrectomy and reconstruction may be necessary.

Patient preparation

♦ Patients with PEH need a broader preoperative evaluation than patients with GERD alone because they tend to be older and have more frequent cardiopulmonary conditions.

♦ In patients with significant preoperative nutritional deficiency or comorbidities that make operative repair too risky, endoscopic management may be best. One or sometimes two percutaneous gastrostomy tubes may provide gastric fixation and can also aid with postoperative nutrition.

Objective testing

♦ A barium swallow can be used to assist in determining anatomy and operative planning.

♦ Upper endoscopy helps to identify mucosal erosions as a source of gastrointestinal bleeding and can rule out Barrett’s esophagus and malignancy. This test should be attempted knowing that sometimes it is technically impossible to obtain.

♦ Esophageal motility study and 24-hour pH studies are difficult to perform because they require intraesophageal positioning of the catheter or probe. Fortunately, the incidence of motility disorders is rare in this population, and there is no need to prove esophageal acid exposure before operating on the patient.

♦ Pulmonary function tests should be performed in patients with a history of shortness of breath or impaired exercise tolerance. Significant improvement in restrictive lung disease can be expected after surgery.

Equipment and instrumentation

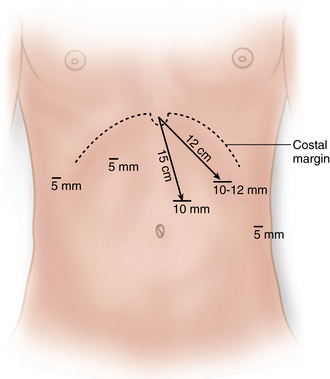

♦ The procedure is performed through five ports: three 5-mm ports and two 10-mm ports. The left upper quadrant 10-mm port can be upsized to accommodate a roticulating endoscopic stapler if an esophageal lengthening procedure is to be performed.

♦ A 30-degree 10-mm laparoscope is used.

♦ A ¼-inch 4-cm long Penrose drain secured with a chromic Endoloop is useful for retracting the upper stomach.

♦ Advanced laparoscopic instruments are needed, including atraumatic bowel graspers such as Hunter graspers (Jarit), laparoscopic Metzenbaum scissors, and needle drivers.

♦ The hook electrocautery is fast and can be used for much of the dissection of the crura. The laparoscopic 5-mm curved harmonic scalpel (ultrasonic coagulator) is used for division of the short gastric vessels and mediastinal dissection.

Anesthesia

♦ Patients with severe carbon dioxide retention, noted during the preoperative workup, can be difficult to manage intraoperatively. The anesthesiologist can reduce CO2 retention by increasing minute ventilation, and the surgeon can decrease the level of CO2 absorption by decreasing the pneumoperitoneum. An alternative insufflating agent such as nitrous oxide can be used.

♦ Following induction of general anesthesia, an orogastric tube and Foley catheter are placed. If there is difficulty passing the orogastric tube, it should not be forced, but it should be attempted again after the contents of the sac have been reduced.

Room setup and patient positioning

♦ The patient is placed supine on a split leg table with arms out and the legs abducted in a 45-degree angle at the hip. Footplates are used to prevent sliding when the patient is placed in reverse Trendelenburg position.

♦ The surgeon stands between the patient’s legs to allow for the best access to the hiatus. The assistant stands on the patient’s left side. Monitors are placed at the head of the table.

Step 3. Operative steps

Access and port placement

♦ The abdomen is insufflated using a Veress needle at the umbilicus or in the left upper quadrant when a prior midline incision was made.

♦ The procedure is performed through five ports.

A 10-mm camera port is placed 15 cm below the xiphoid and just to the left of the midline to avoid the falciform ligament (Figure 5-1). This port needs to be high on the abdomen so that visualization into the mediastinum is possible if an extended mediastinal dissection is necessary (shortened esophagus).

A 10-mm camera port is placed 15 cm below the xiphoid and just to the left of the midline to avoid the falciform ligament (Figure 5-1). This port needs to be high on the abdomen so that visualization into the mediastinum is possible if an extended mediastinal dissection is necessary (shortened esophagus). The surgeon’s right hand access is through a 10-mm port along the left costal margin, 12 cm from the xiphoid process.

The surgeon’s right hand access is through a 10-mm port along the left costal margin, 12 cm from the xiphoid process. A 5-mm port is placed in a right lateral position just off the costal margin for the liver retractor. Retraction of the left lobe of the liver to expose the hiatus can be achieved with a 5-mm “triangle” retractor, fixed to a flexible retractor arm “snake” mounted to the Bookwalter post on the right side of the table. Alternatively, the Nathanson retractor can be placed through a 5-mm subxiphoid port and mounted from the left side.

A 5-mm port is placed in a right lateral position just off the costal margin for the liver retractor. Retraction of the left lobe of the liver to expose the hiatus can be achieved with a 5-mm “triangle” retractor, fixed to a flexible retractor arm “snake” mounted to the Bookwalter post on the right side of the table. Alternatively, the Nathanson retractor can be placed through a 5-mm subxiphoid port and mounted from the left side. The assistant uses a 5-mm port in the left flank, anterior axillary line, approximately 4 to 6 cm inferior to the surgeon’s right-hand port.

The assistant uses a 5-mm port in the left flank, anterior axillary line, approximately 4 to 6 cm inferior to the surgeon’s right-hand port. The final port placed is a 5-mm port in the right upper abdomen for the surgeon’s left hand access. It is placed just off the costal margin in the midclavicular line. This port needs to be as high as possible on the abdomen to reach up into the mediastinum. Its position is determined by the level of the liver.

The final port placed is a 5-mm port in the right upper abdomen for the surgeon’s left hand access. It is placed just off the costal margin in the midclavicular line. This port needs to be as high as possible on the abdomen to reach up into the mediastinum. Its position is determined by the level of the liver.Reduction of the hernia

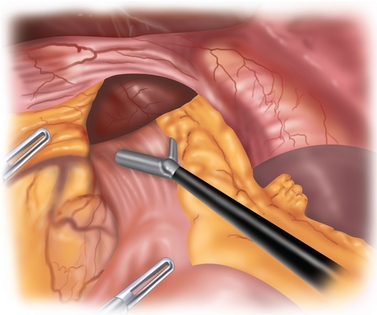

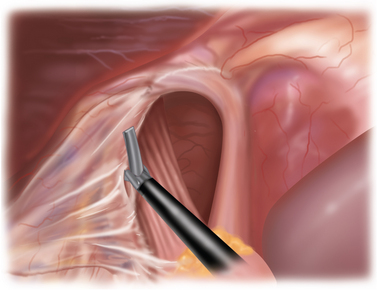

The hernia is reduced with the aid of gravity and gentle traction. The table is placed in steep reverse Trendelenburg, which does much of the work of retraction. The assistant retracts the herniated contents inferiorly, and the surgeon pulls the GE junction out of the mediastinum (Figure 5-2).

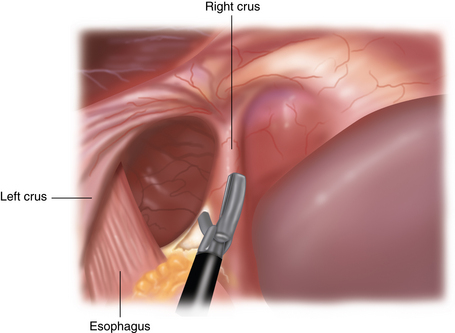

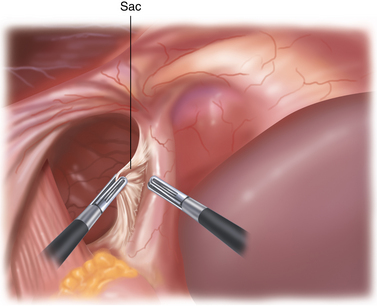

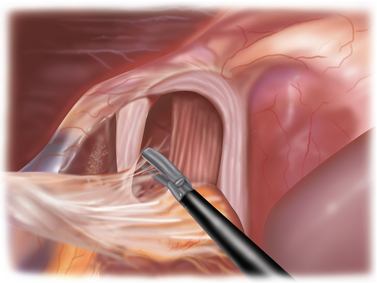

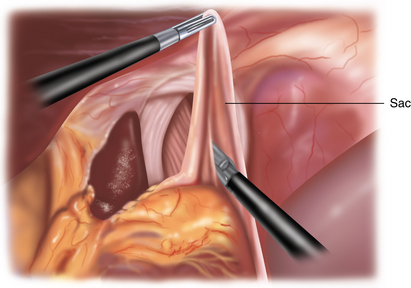

Different from a standard procedure fundoplication, the surgeon begins at the left crus of the diaphragm, not the right. The peritoneum overlying the abdominal side of the left crus is opened (Figure 5-3). The sac is then pulled inferiorly and medially out of the chest and away from the mediastinal pleura, which appears much whiter than the sac (Figure 5-4).

Excision of the sac

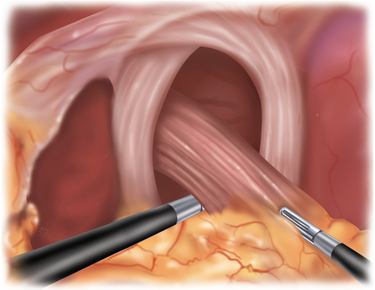

♦ The dissection continues up and over the anterior aspect of the crural defect to expose the right crus (Figure 5-5). The assistant can hold the sac to prevent it from retracting into the chest.

♦ The sac will be attached to the mediastinum with filmy adhesions, which can be torn easily. If the tissue does not tear easily with two grasps, then you have probably encountered a blood vessel. The Harmonic scalpel should be used to provide hemostasis in addition to division (Figure 5-6).

♦ To remove the sac, it must be divided from the gastroesophageal fat pad (Figure 5-7). Although the inclination is to “clean off” the GE junction, it is, in fact, more prudent to divide the sac a fair distance away from the GE fat pad to avoid inadvertent injury to the anterior vagus. The anterior vagus can be displaced off of the esophagus because of the hernia.

♦ Mobilization of the fundus is necessary to facilitate the posterior dissection. The short gastric vessels (which are frequently quite long) are divided using the ultrasonic dissector. The surgeon retracts the stomach to the patient’s right side, while the assistant retracts the short gastric vessels anteriorly and laterally. As you approach the top of the stomach where the vessels are shorter, the assistant can retract the posterior fundus (“behind” the short gastrics) to the patient’s right side, which will tent the vessels and avoid thermal spread to the stomach wall.

♦ The posterior sac is then reduced and detached from the crura. It is not easily defined like the anterior sac. It is important that the posterior crura are cleared of attachments before suturing them closed.

Establishment of adequate intra-abdominal esophageal length

♦ It is helpful to encircle the esophagus with a 4-cm long, ¼-inch wide Penrose drain secured with an Endoloop (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts). The assistant retracts the esophagus to the patient’s right, allowing visualization of the retroesophageal window, the left crus, and dissection can be continued if necessary. The posterior vagus is adjacent to the esophagus, wrapped within the Penrose drain.

♦ At least 2 cm of intra-abdominal esophagus below the level of the crura is necessary for completing the wrap. If there is inadequate length, an extensive mediastinal esophageal mobilization should be undertaken. This is usually all that is needed to obtain the needed length.

Closure of the hiatal defect

♦ The diaphragmatic defect is closed posteriorly with interrupted 0-silk, or 0-Ethibond (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) suture, starting at the base of the crura. In large hernias, the crura often lack integrity and will need to be reinforced with pledgets.

♦ The pledgets should be sized so that they do not come in contact with the esophagus but lie exclusively on the crura (Figure 5-8).

Mesh reinforcement

♦ Biologic mesh has been shown to reduce hernia recurrence when compared to primary repair. The mesh needs to be sutured to the diaphragm to prevent malpositioning.

♦ After the hiatus is closed posteriorly, a piece of mesh is fashioned in a U-shape and secured to the diaphragm using interrupted silk sutures. Placing spiral tacks in this area is discouraged, as there have been reports of penetration of the pericardium.

Fundoplication

♦ A fundoplication should be performed to both prevent postoperative reflux and provide further anchoring of the stomach and esophagus intra-abdominally.

♦ The fundus should be free to pass behind the esophagus without traction.

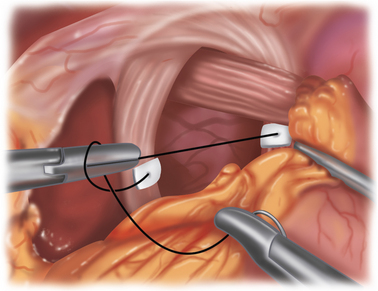

♦ A floppy 2-cm long 360-degree wrap is performed over a 56 to 60 Fr bougie. The fundoplication is secured using three 2-0 nonabsorbable sutures (silk or Ethibond). Each stitch should incorporate a full thickness of stomach and partial thickness of esophagus (Figure 5-9).

Collis gastroplasty

In patients with shortened esophagus, a Collis gastroplasty should be performed.

♦ Extensive mediastinal mobilization at least 4 to 6 cm above the GE junction is carried out.

♦ The orogastric tube is replaced with a 48 Fr bougie, and a point 3 cm inferior to the angle of His, just lateral to the bougie, is marked with electrocautery.

♦ A roticulating 45-mm endoscopic stapler is introduced into the abdomen through the left subcostal port and fired transversely across the fundus until the marked point is reached.

♦ The stapler is then reloaded and fired parallel to the esophagus, abutting the bougie, so that a wedge of gastric fundus approximately 15 mL in volume is removed. This creates the neo-esophagus that is approximately 3 to 4 cm in length.

♦ After stapling is complete, the bougie is replaced with an orogastric tube, and 250 mL of methylene blue is used to fill the stomach and test the staple lines for leaks.

Gastropexy

♦ A gastropexy may help to prevent recurrent herniation of the stomach into the chest from constant positive intra-abdominal pressure or crural disruption.

♦ Two 0-Prolene sutures are placed in the midbody of the stomach in an area that will easily reach the anterior abdominal wall. Each tail is then brought out through the skin at two separate fascia puncture sites and secured.

Step 4. Postoperative care

Inpatient management

♦ Patients may begin liquids on the first postoperative day, or if extensive dissection was required, a contrast swallow study may be performed prior to starting a diet.

♦ Postoperative nausea is treated aggressively. For the first 24 hours postoperatively, patients are placed on around-the-clock antiemetic regimens.

♦ Patients are usually discharged on the second postoperative day on a full liquid diet.

♦ The diet is then advanced over the next few days to soft solid food. Patients remain on soft solids for 3 to 4 weeks.

Long-term management

♦ Patients are instructed to avoid breads, dry meats, and carbonated beverages.

♦ If the prescribed diet is followed, most patients will not complain of dysphagia. When symptoms are present with liquids or if solids are not tolerated after 3 to 4 weeks, then an upper gastrointestinal contrast study can be helpful. Ultimately, endoscopic dilation may be needed.

♦ Over the long term, many patients after surgery will have abnormalities found on upper gastrointestinal contrast studies; however, most of these patients are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ An antireflux procedure should be performed on patients undergoing PEH repair because the majority of them will have abnormal 24-hr pH studies postoperatively without it.

♦ During the reduction of the hernia sac, constant attention to the location and preservation of the vagus nerves, esophagus, and aorta should be maintained. The vagus nerves should be identified and preserved to avoid postoperative gastroparesis.

♦ Complete sac mobilization and resection should be achieved.

♦ The most challenging aspect of a laparoscopic PEH repair is dissection of the inferior left crus. The key to achieving this is adequate esophageal mobilization and division of the short gastric vessels.

♦ Most cases of shortened esophagus are corrected with extensive mediastinal mobilization. This may eliminate the need for an esophageal lengthening procedure.

♦ If the mediastinal pleura is entered, laparoscopic dissection should continue unless the patient’s condition deteriorates. Repair of the pleura can potentially create a dangerous flap that may lead to a tension pneumothorax.

♦ The use of prosthetic mesh at the hiatus introduces a potentially catastrophic outcome for patients: erosion into the esophagus. Biologic materials offer a safer and equally effective alternative for bolstering the crural repair.

Low DE, Simchuk EJ. Effect of paraesophageal hernia repair on pulmonary function. Ann Surg. 2002;74:333-337.

Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter J, et al. Biologic prosthesis reduces recurrence after lap paraesophageal hernia repair: a multi-center prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2006;244;4:481-490.

Ponsky J, Rosen M, Fanning A, et al. Anterior gastropexy may reduce the recurrence rate after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(7):1036-1041.

Stylopoulos N, Gazelle GS, Rattner DW. Paraesophageal hernias: operation or observation. Ann Surg. 2002;236;4:492-501.

Swanstrom LL, Marcus DR, Galloway GQ. Laparoscopic Collis gastroplasty is the treatment of choice for the shortened esophagus. Am J Surg. 1996;171(5):477-481.

Tsereteli Z, Terry ML, et al. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195(2):173-179.