Papulosquamous and Lichenoid Disorders

Kelly M. Cordoro, Joshua Schulman

Papulosquamous disorders

Psoriasis

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, inflammatory papulosquamous disease with an estimated prevalence of 1% in children.1 Pediatric psoriasis is subdivided into congenital, infantile, and childhood, defined as psoriasis presenting at birth, in the first year of life, and between ages 1 and 18 years, respectively. One-third of all patients develop psoriasis in the first two decades of life. Up to 30% of these patients manifest by age 2 with psoriatic diaper rash.2–4 Age of onset may predict disease severity. In a large cohort study of childhood psoriasis, for every year increase in age of onset from birth to 18 years, there was a 10% decrease in risk of moderate–severe disease.5 Precipitating factors are more common in childhood compared with adult-onset psoriasis. Trauma (via Koebner phenomenon) and infections (pharyngeal and perianal group A streptococci in particular) are frequently implicated in initiation and exacerbation of early-onset psoriasis.6 Psoriasis arising during the acute and convalescent phases of Kawasaki disease has been reported in infants as young as 3 months.7

While psoriasis is diagnosed by the presence of characteristic clinical features, diagnosis in the neonatal and infantile period can be challenging because of clinical overlap with other common papulosquamous eruptions. A skin biopsy may be required to confirm the diagnosis in severe or worrisome cases. Otherwise, tincture of time often illuminates the correct diagnosis as the disease evolves towards more classic features.

Cutaneous findings

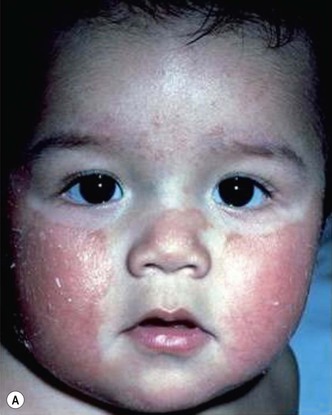

Plaque and guttate psoriasis are the most common morphologies observed in children. Individual lesions of typical psoriasis consist of erythematous, well-demarcated plaques with silvery-white scale. Guttate, or ‘drop-like’ psoriasis is an eruption of individual papules and small plaques up to 1 cm in size (Fig. 16.1). Psoriasis in infants offers unique variations of morphology and distribution. For example, annular and serpiginous patterns are common (Fig. 16.2) and involvement of the face and anogenital region is typical (Fig. 16.3). Scale may be imperceptible in psoriasis arising in the diaper area, folds and flexures. The Koebner phenomenon (isomorphic response or psoriasis arising at sites of trauma) is commonly observed and may explain the common distributions of psoriasis in the diaper area, scalp and face of infants, as opposed to adults (Fig. 16.4![]() ). Nail changes are present in 10% of infants with psoriasis and may include pitting, onycholysis, oil spots, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Pruritus is common. Box 16.1 summarizes the clinical variants and distributions of psoriasis in children.

). Nail changes are present in 10% of infants with psoriasis and may include pitting, onycholysis, oil spots, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Pruritus is common. Box 16.1 summarizes the clinical variants and distributions of psoriasis in children.

Diaper psoriasis.

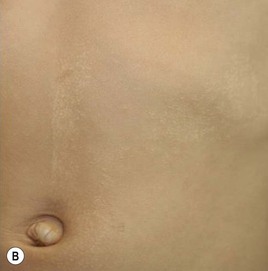

In children younger than 2 years of age, psoriatic diaper rash is a common presentation (see also Chapter 17). It presents as bright red, glazed appearing, well-marginated individual or confluent plaques with absent or minimal scale, involving the anogenital area including skin folds. It often expands toward the abdomen and thighs where the scale becomes more perceptible (Fig. 16.5![]() ). In some cases, there is widespread dissemination of the psoriasis shortly after the diaper eruption appears, referred to as psoriatic diaper rash with dissemination or as diaper dermatitis with psoriasiform id reaction (Fig. 16.6).8 Psoriasis and other acute diaper rashes, such as Candida, may result in a psoriasiform id reaction (Fig. 16.7

). In some cases, there is widespread dissemination of the psoriasis shortly after the diaper eruption appears, referred to as psoriatic diaper rash with dissemination or as diaper dermatitis with psoriasiform id reaction (Fig. 16.6).8 Psoriasis and other acute diaper rashes, such as Candida, may result in a psoriasiform id reaction (Fig. 16.7![]() ). The initial stages of diaper (‘napkin’) psoriasis are easily confused with other diaper rashes, including irritant dermatitis (which typically spares the folds), Candida infection, seborrheic dermatitis as well as other causes. Infants with diaper psoriasis with dissemination of lesions to other areas of the body and a positive first-degree family history of psoriasis are probably at greatest risk for developing typical psoriasis later in life.9–11

). The initial stages of diaper (‘napkin’) psoriasis are easily confused with other diaper rashes, including irritant dermatitis (which typically spares the folds), Candida infection, seborrheic dermatitis as well as other causes. Infants with diaper psoriasis with dissemination of lesions to other areas of the body and a positive first-degree family history of psoriasis are probably at greatest risk for developing typical psoriasis later in life.9–11

Treatment consists of bland emollients and topical anti-inflammatory agents used in combination. Ointment formulations tend to have greater efficacy and tolerability (i.e., less burning with application) than creams. Effective agents include low to mid-potency topical steroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, low concentrations of liquor carbonis detergens (3–5% LCD) compounded in either white petrolatum or low potency topical steroid, and topical vitamin D analogs such as calcitriol or calcipotriene.

Erythrodermic psoriasis.

Psoriasis presenting as congenital or neonatal erythroderma is a rare, but documented, presentation.12,13 Neonatal erythrodermic psoriasis has overlapping features with primary immunodeficiency syndromes, Netherton syndrome, metabolic disorders, systemic infections, and certain forms of ichthyosis. A positive family history of psoriasis, patchy rather than diffuse involvement, and absence of other features of ichthyosis (e.g., ectropion and eclabium) may help to differentiate psoriasis from ichthyosis in early life.14 The prognosis is guarded. Evolution over time often results in typical localized psoriatic plaques or the erythroderma may persist.12 This presentation is also potentially life-threatening. The impaired skin barrier confers a risk of hyperpyrexia, hypernatremic dehydration, hypoalbuminemia, septicemia, and cutaneous infections. Management consists of optimized nutritional status and fluid and electrolyte balance. Control of inflammation with topical steroids and barrier reinforcement with bland emollients to prevent further metabolic disarray and infections is imperative.

Pustular psoriasis.

Pustular psoriasis in infancy may be localized or generalized. Generalized pustular psoriasis of von Zumbusch (GPP) is characterized by fever and an explosive eruption of sheets of sterile pustules on inflamed skin (Fig. 16.8). The pustules may be arranged at the periphery of annular or serpiginous plaques (Fig. 16.9). Annular pustular psoriasis, alone or together with generalized pustulation, is the most common form observed in children. Affected children may appear well or exhibit systemic symptoms of progressive malaise, lethargy, irritability and unwillingness to eat. GPP runs an unpredictable course with relapses and remissions. Severe, localized pustular psoriasis of the nail unit (acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau) may occur in isolation or accompany generalized pustular psoriasis.

Pustular psoriasis localized to the intertriginous areas, particularly the neck, is a relatively uncommon subtype that may be misdiagnosed as bacterial or candidal intertrigo. Affected infants are often 1–2 months old and otherwise well. There may be a positive family history of psoriasis. This localized intertriginous variant may progress to widespread disease requiring systemic therapy.15

The differential diagnosis of neonatal and infantile pustulosis includes a recently described rare condition, ‘deficiency of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist’ (DIRA). DIRA is an autosomal recessive, early-onset, life-threatening autoinflammatory syndrome primarily affecting the skin and bones. Patients typically present as neonates or young infants with a localized or generalized pustular eruption, desquamation, multifocal osteomyelitis and periostitis, failure to thrive, and elevated inflammatory markers (Fig. 16.10).16 DIRA is mediated by mutations in the IL1RN gene encoding the interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist, resulting in unopposed, widespread systemic inflammation. The allele frequencies of the causative mutations are highest in patients from Puerto Rico, the Netherlands, and Newfoundland. IL1RN gene sequencing is diagnostic. These patients require targeted therapy with the recombinant human IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra.16,17

Other entities in the differential diagnosis of pustular psoriasis include: viral, fungal, and bacterial infections; secondarily infected atopic or seborrheic dermatitis; acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; pityriasis rubra pilaris; scabies; miliaria; acrodermatitis enteropathica; eosinophilic pustular folliculitis; erythema toxicum neonatorum; the pustular leukemoid reaction associated with Trisomy 21; and transient neonatal pustular melanosis.

The treatment of GPP varies. Milder cases can be controlled with topical corticosteroids and vitamin D analogs. Severe cases may require hospitalization for work-up, supportive care and initiation of systemic therapy. Cultures should be obtained from pustular lesions, and if repeatedly sterile, should alert physicians to the diagnosis of pustular psoriasis. Oral retinoids, cyclosporine, methotrexate and phototherapy comprise the most commonly used and effective agents for severe, refractory or multiply-relapsed pustular psoriasis. Older children with disease refractory to traditional systemic medications may respond to anti-TNF therapy.18

Congenital psoriasis.

Psoriasis presenting at birth is very rare. Only nine published cases of congenital psoriasis are diagnostically convincing. Of those, plaque, erythrodermic and pustular were the most common clinical subtypes observed. Although no consistent anatomic distribution has been distinguished, the scalp, face, extremities and trunk are commonly involved. Notably, the diaper area is frequently spared, perhaps due to lack of trauma from diapers.19 Histologically confirmed congenital psoriasis occurring along Blaschko’s lines has been reported. Females are more frequently affected with Blaschko-linear psoriasis presumably due to functional X-chromosome mosaicism.20 A maternal and family history of psoriasis is often absent in cases of congenital psoriasis.19

The differential diagnosis of congenital psoriasis depends on the presentation. Erythrodermic and papulosquamous cases should be distinguished from seborrheic dermatitis, including localized ‘cradle cap’, congenital or neonatal candidiasis, immunodeficiency syndromes, congenital ichthyosis and Netherton syndrome.21 Linear psoriasis must be differentiated from inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevi.22 The differential diagnosis for congenital pustular psoriasis includes: bacterial infections; candidiasis; erythema toxicum neonatorum; pustular leukemoid reaction in children with Trisomy 21; transient neonatal pustular melanosis; Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis; and deficiency of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (DIRA, see above). Alternatively, congenital psoriasis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of newborns with erythroderma, or papulosquamous or pustular eruptions.

Treatment for congenital psoriasis should be conservative initially with bland emollients and topical steroids. A ‘soak and seal’ regimen using wet wraps with low potency topical steroids can enhance efficacy. Systemic therapy with acitretin or methotrexate is required in some cases. Response to therapy is variable and depends on disease severity.

Long-term prognosis of congenital psoriasis is unknown because follow-up is unavailable for most cases. Infants with presumed pustular psoriasis, failure to thrive, skeletal anomalies and systemic symptoms who are refractory to therapy should be evaluated for DIRA.

Extracutaneous findings of infantile psoriasis

Pustular and erythrodermic psoriasis may be accompanied by systemic signs including fever, chills, irritability, lethargy, dehydration, and fluid and electrolyte imbalance, as discussed previously. Psoriatic arthritis is the most common comorbid association in childhood psoriasis but is infrequent in infants. Nail pitting, dactylitis, and enthesitis may be markers of children at risk for arthritis.23 There is evidence that children with psoriasis, regardless of severity, are more likely to be overweight or obese and thus at increased risk for related complications.24 A potential relationship between pediatric psoriasis and the metabolic syndrome requires further investigation.25 At present, there are no data linking infantile psoriasis with obesity or metabolic syndrome.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis depends on the specific morphology and distribution. Scalp psoriasis may resemble seborrheic or atopic dermatitis in infants. Tinea capitis more frequently has alopecia or hair breakage and can be distinguished with fungal culture. Plaque and guttate psoriasis must be differentiated from neonatal lupus, pityriasis alba, nummular atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and tinea corporis. Atopic dermatitis is usually associated with significantly more pruritus and often with other atopic stigmata or family history. Possible infectious etiologies must be considered in pustular psoriasis. Kawasaki disease may display psoriasis-like eruptions in infants, but has other characteristic features which can aid in diagnosis.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease that results in accelerated epidermal cell turnover observed clinically as scaly red plaques. The dysregulated cutaneous immune response is modified by environmental factors in genetically susceptible individuals.26 Psoriasis following bacterial infections as well as Kawasaki disease suggests the potential pathogenic role of superantigens.27,28 A family history of psoriasis is often absent in infantile cases but the rate climbs to 80% in older children.2,4 HLA-Cw6 is the major risk allele that confers susceptibility to early-onset psoriasis.29

Characteristic histology of plaque psoriasis includes parakeratosis, loss of the granular layer, Munro microabscesses, spongiform pustules of Kogoj and a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Pustular psoriasis features intraepidermal subcorneal pustules and a mixed dermal inflammatory infiltrate.

Treatment and prognosis

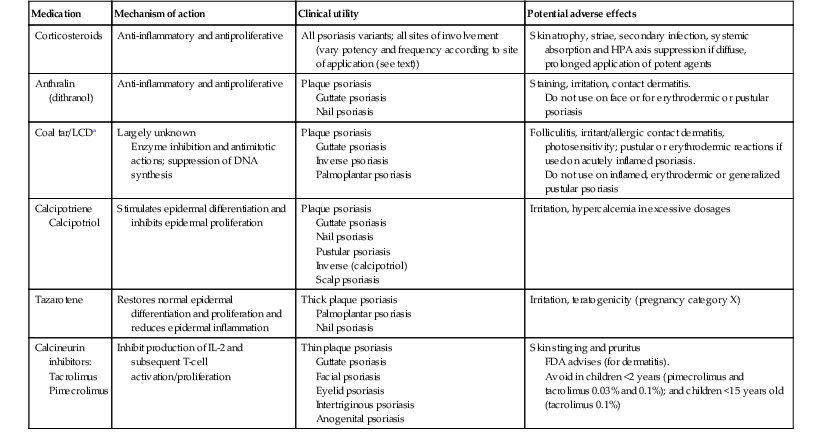

As a chronic disease, psoriasis is characterized by intermittent exacerbations and spontaneous remissions. The choice of treatment is determined by disease morphology, distribution, severity, comorbidities and patient age. Conservative management with cautious progression to systemic therapies in critical cases is recommended for infantile psoriasis. Topical therapies including bland emollients, corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, topical calcineurin inhibitors, anthralin and tar-based preparations (liquor carbonis detergens 3–5%) may be tried initially and are often all that is necessary for thin plaque or guttate psoriasis.

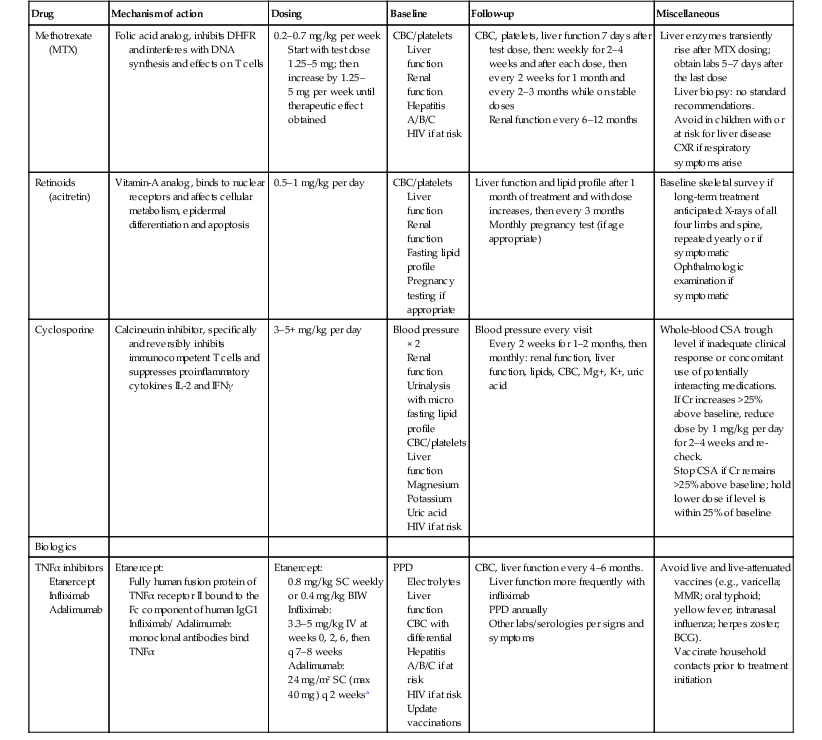

Severe or rapidly progressive disease refractory to combination topical therapy may require systemic therapy with retinoids, cyclosporine, methotrexate or conservative doses of narrow band UVB phototherapy. Systemic agents require close clinical and laboratory monitoring. Table 16.1 reviews the various topical therapies and Table 16.2![]() the systemic agents available to treat childhood psoriasis. Comprehensive reviews of management principles for pediatric psoriasis have been recently published.5,30

the systemic agents available to treat childhood psoriasis. Comprehensive reviews of management principles for pediatric psoriasis have been recently published.5,30

TABLE 16.1

Selected topical therapies for childhood psoriasis

| Medication | Mechanism of action | Clinical utility | Potential adverse effects |

| Corticosteroids | Anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative | All psoriasis variants; all sites of involvement (vary potency and frequency according to site of application (see text)) | Skin atrophy, striae, secondary infection, systemic absorption and HPA axis suppression if diffuse, prolonged application of potent agents |

| Anthralin (dithranol) | Anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative | Plaque psoriasis Guttate psoriasis Nail psoriasis |

Staining, irritation, contact dermatitis. Do not use on face or for erythrodermic or pustular psoriasis |

| Coal tar/LCDa | Largely unknown Enzyme inhibition and antimitotic actions; suppression of DNA synthesis |

Plaque psoriasis Guttate psoriasis Inverse psoriasis Palmoplantar psoriasis |

Folliculitis, irritant/allergic contact dermatitis, photosensitivity; pustular or erythrodermic reactions if used on acutely inflamed psoriasis. Do not use on inflamed, erythrodermic or generalized pustular psoriasis |

| Calcipotriene Calcipotriol |

Stimulates epidermal differentiation and inhibits epidermal proliferation | Plaque psoriasis Guttate psoriasis Nail psoriasis Pustular psoriasis Inverse (calcipotriol) Scalp psoriasis |

Irritation, hypercalcemia in excessive dosages |

| Tazarotene | Restores normal epidermal differentiation and proliferation and reduces epidermal inflammation | Thick plaque psoriasis Palmoplantar psoriasis Nail psoriasis |

Irritation, teratogenicity (pregnancy category X) |

| Calcineurin inhibitors: Tacrolimus Pimecrolimus |

Inhibit production of IL-2 and subsequent T-cell activation/proliferation | Thin plaque psoriasis Guttate psoriasis Facial psoriasis Eyelid psoriasis Intertriginous psoriasis Anogenital psoriasis |

Skin stinging and pruritus FDA advises (for dermatitis). Avoid in children <2 years (pimecrolimus and tacrolimus 0.03% and 0.1%); and children <15 years old (tacrolimus 0.1%) |

a Liquor carbonis detergens.

Adapted from Cordoro KM. Management of childhood psoriasis. Adv Dermatol 2008; 24:125–169.

TABLE 16.2

Systemic agents for psoriasis and suggested monitoring

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Dosing | Baseline | Follow-up | Miscellaneous |

| Methotrexate (MTX) | Folic acid analog, inhibits DHFR and interferes with DNA synthesis and effects on T cells | 0.2–0.7 mg/kg per week Start with test dose 1.25–5 mg; then increase by 1.25–5 mg per week until therapeutic effect obtained |

CBC/platelets Liver function Renal function Hepatitis A/B/C HIV if at risk |

CBC, platelets, liver function 7 days after test dose, then: weekly for 2–4 weeks and after each dose, then every 2 weeks for 1 month and every 2–3 months while on stable doses Renal function every 6–12 months |

Liver enzymes transiently rise after MTX dosing; obtain labs 5–7 days after the last dose Liver biopsy: no standard recommendations. Avoid in children with or at risk for liver disease CXR if respiratory symptoms arise |

| Retinoids (acitretin) |

Vitamin-A analog, binds to nuclear receptors and affects cellular metabolism, epidermal differentiation and apoptosis | 0.5–1 mg/kg per day | CBC/platelets Liver function Renal function Fasting lipid profile Pregnancy testing if appropriate |

Liver function and lipid profile after 1 month of treatment and with dose increases, then every 3 months Monthly pregnancy test (if age appropriate) |

Baseline skeletal survey if long-term treatment anticipated: X-rays of all four limbs and spine, repeated yearly or if symptomatic Ophthalmologic examination if symptomatic |

| Cyclosporine | Calcineurin inhibitor, specifically and reversibly inhibits immunocompetent T cells and suppresses proinflammatory cytokines IL-2 and IFNγ | 3–5+ mg/kg per day | Blood pressure × 2 Renal function Urinalysis with micro fasting lipid profile CBC/platelets Liver function Magnesium Potassium Uric acid HIV if at risk |

Blood pressure every visit Every 2 weeks for 1–2 months, then monthly: renal function, liver function, lipids, CBC, Mg+, K+, uric acid |

Whole-blood CSA trough level if inadequate clinical response or concomitant use of potentially interacting medications. If Cr increases >25% above baseline, reduce dose by 1 mg/kg per day for 2–4 weeks and re-check. Stop CSA if Cr remains >25% above baseline; hold lower dose if level is within 25% of baseline |

| Biologics | |||||

| TNFα inhibitors Etanercept Infliximab Adalimumab |

Etanercept: Fully human fusion protein of TNFα receptor II bound to the Fc component of human IgG1 Infliximab/ Adalimumab: monoclonal antibodies bind TNFα |

Etanercept: 0.8 mg/kg SC weekly or 0.4 mg/kg BIW Infliximab: 3.3–5 mg/kg IV at weeks 0, 2, 6, then q 7–8 weeks Adalimumab: 24 mg/m2 SC (max 40 mg) q 2 weeksa |

PPD Electrolytes Liver function CBC with differential Hepatitis A/B/C if at risk HIV if at risk Update vaccinations |

CBC, liver function every 4–6 months. Liver function more frequently with infliximab PPD annually Other labs/serologies per signs and symptoms |

Avoid live and live-attenuated vaccines (e.g., varicella; MMR; oral typhoid; yellow fever; intranasal influenza; herpes zoster; BCG). Vaccinate household contacts prior to treatment initiation |

a Dosing from published experience in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis; in two case reports in pediatric psoriasis, dosing was 40 mg q 2 weeks in two adolescent patients.

CBC, complete blood count; Cr, creatinine; CSA, cyclosporine; CXR, chest X-ray; MTX, methotrexate; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-2, interleukin-2; IFNγ, interferon-gamma; PPD, purified protein derivative; MMR, measles-mumps-rubella vaccine; BCG, Bacillus Calmette–Guérin; BIW, twice weekly.

Adapted from Cordoro KM. Management of childhood psoriasis. Adv Dermatol 2008; 24:125–169; and Marqueling AL, Cordoro KM. Systemic treatments for severe pediatric psoriasis: a practical approach. Dermatol Clin 2013; 31:267–288.

The prognosis of the various forms of infantile psoriasis is variable and requires further study. A positive family history of psoriasis and initial presentation with guttate morphology may predict more severe plaque psoriasis later in life.31

Pityriasis rubra pilaris

Introduction

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a papulosquamous disorder of unknown etiology. The age of onset is bimodal, with peaks in the first and fifth decades of life. Reports of PRP in children less than 2 years old date back to 1905.32 Griffiths originally classified patients with PRP into five types based on clinical features, age of onset and prognosis. Type I and II are adult-onset forms (classic and atypical, respectively) and types III, IV, and V represent the juvenile-onset spectrum.33 Each juvenile type of PRP may arise in infancy and early childhood (see Table 16.3![]() ).

).

TABLE 16.3

Major types of pityriasis rubra pilaris that present in infants or neonates

| Type | Clinical features | Notes |

| III classic juvenile | May present as erythroderma. Whitish flaky scale on face and scalp. Follicular keratotic papules and scaly red patches spread cephalocaudally; may develop salmon colored erythroderma admixed with foci of normal skin. Most have palmoplantar keratoderma | May present in first few years of life Over time, the follicular component may be lost and lesions appear more like psoriasis Ectropion in severe cases |

| IV circumscribed juvenile | Well-demarcated plaques on elbows, knees, ankles, dorsal hands and feet. Some have palmoplantar keratoderma | Most common in pre-adolescents but can present in first few years of life |

| V atypical juvenile | Follicular hyperkeratosis, erythema and ichthyosiform dermatitis. Sclerodermoid appearance of hands and feet; may develop contractures | May be congenital and familial. May arise in first few years of life |

| Acute post-infectious | Initially resembles superantigen-mediated disease followed by classic features similar to type III | Infants and young children. Follows infection |

Type III classic juvenile PRP and type IV circumscribed juvenile PRP are more common in older children but can occur early in life. An acute post-infectious form of PRP, which has similar morphologic features to type III, has been observed in infants and young children.34,35 Type V atypical juvenile PRP may be congenital or develop within the first few years.33,36 A positive family history of PRP is reported in up to 6.5% of patients. These rare familial cases are typically inherited in autosomal dominant fashion and fit clinically into type V.37,38 Griffiths surmised that more than one disease is probably represented in some cases designated as type V PRP, including forms of congenital follicular ichthyosis.33

Cutaneous findings

There is considerable heterogeneity and overlap of clinical features among the various types of PRP in children (Table 16.3![]() ). The classic findings of PRP are follicular hyperkeratosis, scattered salmon-colored scaly patches and plaques, varying degrees of erythroderma, and palmoplantar keratoderma. Though the classic primary lesion of PRP is a follicular keratotic papule, this is not universally observed. Neonates and infants may present with erythroderma.39 Diagnosis is based on distinctive clinical features and supportive histopathology.

). The classic findings of PRP are follicular hyperkeratosis, scattered salmon-colored scaly patches and plaques, varying degrees of erythroderma, and palmoplantar keratoderma. Though the classic primary lesion of PRP is a follicular keratotic papule, this is not universally observed. Neonates and infants may present with erythroderma.39 Diagnosis is based on distinctive clinical features and supportive histopathology.

Type III classic juvenile PRP often starts on the face and scalp with fine, whitish, powdery scale. The upper trunk develops an eruption of follicular hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce and progress in a cephalocaudal direction towards generalized erythroderma with islands of sparing (Figs 16.11A–C, 16.12![]() ). The erythroderma is orange-yellow, salmon, or red-brown in color.33 Ectropion may develop if facial involvement is severe.33,36 A salmon-colored palmoplantar keratoderma with fissures is common and may be the presenting feature (Fig. 16.11D). Over time, the follicular component may be lost and psoriasiform morphology becomes more prominent, especially on the knees and elbows. Nails have longitudinal ridges and subungual hyperkeratosis but pitting and ‘oil spots’ characteristic of psoriasis are notably absent.33 Pruritus, if present, is usually mild. Sweating may be impaired in affected skin.

). The erythroderma is orange-yellow, salmon, or red-brown in color.33 Ectropion may develop if facial involvement is severe.33,36 A salmon-colored palmoplantar keratoderma with fissures is common and may be the presenting feature (Fig. 16.11D). Over time, the follicular component may be lost and psoriasiform morphology becomes more prominent, especially on the knees and elbows. Nails have longitudinal ridges and subungual hyperkeratosis but pitting and ‘oil spots’ characteristic of psoriasis are notably absent.33 Pruritus, if present, is usually mild. Sweating may be impaired in affected skin.

Type IV circumscribed juvenile PRP is characterized by sharply demarcated areas of follicular hyperkeratosis that coalesce to form psoriasiform plaques on the elbows, knees, ankles, and dorsal aspects of the hands and feet. A waxy, orange-red, diffuse palmoplantar keratoderma may be observed. Scaly red patches may appear on other parts of the body and hyperkeratosis overlying bony prominences (elbows, knees, ankles, Achilles tendon) is common.33,40

Type V atypical PRP is characterized by follicular hyperkeratosis, erythema and ichthyosiform dermatitis. The palms and soles may develop a sclerodermoid appearance with tethering and subsequent joint contractures (Fig. 16.13). The familial form of type V PRP exhibits autosomal dominant inheritance and presents at birth or in early infancy, often with head and neck involvement or diffuse erythroderma.37,38

Acute, post-infectious PRP is morphologically similar to type III and occurs after the first year of life in the context of a recent infection. The initial presentation is abrupt, with rapidly progressing rash and systemic signs resembling superantigen-mediated diseases such as staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), scarlet fever, toxic shock syndrome or Kawasaki disease. The initial eruption is followed in days to weeks by the typical features of classic juvenile PRP.34,35,41

Extracutaneous findings

There are no systemic abnormalities independently associated with PRP. Abnormalities identified in patients with post-infectious PRP are due to the underlying infection. Fluid imbalance and metabolic derangements may occur as a consequence of erythroderma.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The etiology and pathogenesis of PRP are not fully understood. PRP is primarily a sporadic disorder, with no clear sex or racial predilection. The observation of pediatric cases following bacterial or viral infections, vaccinations, and cutaneous trauma suggests a reactive process. Superantigens and massive cytokine release likely mediate the post-infectious cases.35,41,42 Familial cases point to disordered keratinization modulated by genetic predisposition. Recently, familial PRP, in four families with disease onset in the first 3 years of life, was found to result from mutations in CARD14. Interestingly, mutations of this gene have been identified in some cases of psoriasis, suggesting that inherited PRP and some forms of psoriasis are allelic.43

The histopathologic features of PRP are found most often in erythrodermic areas and less so in areas of follicular hyperkeratosis. There is epidermal acanthosis with alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis in both vertical and horizontal directions. Perifollicular parakeratosis surrounds dilated, plugged hair follicles. A superficial dermal perivascular and perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate is observed.44

Differential diagnosis

The diagnosis most difficult to differentiate from PRP – both clinically and histopathologically – is psoriasis. The precise relationship between these diseases is unclear, and discriminating between the two in young infants may not be possible. Features favoring PRP include follicular keratotic papules, diffuse palmoplantar keratoderma, lack of mounds of neutrophils on histopathology, and the quality of scalp scale, which tends to be flaky white and powdery in PRP and thick and adherent in psoriasis.

The acute post-infectious form of PRP may be difficult to initially differentiate from superantigen-mediated diseases including SSSS, scarlet fever, Kawasaki disease, and toxic shock syndromes. Other entities in the differential diagnosis include follicular eczema, cutaneous drug eruptions, congenital ichthyosis, lichen planus and other lichenoid diseases, and keratosis pilaris. The circumscribed form may closely resemble progressive symmetric erythrokeratodermia (PSEK), which is characterized by well-defined red scaly plaques symmetrically distributed on the face, extremities, and buttocks. Half of patients with PSEK have palmoplantar keratoderma but follicular hyperkeratosis is not observed.

Prognosis

The course and prognosis of neonates and infants with PRP is unpredictable. The disease morphology and extent may evolve over time with or without treatment. Features that overlap with other forms of PRP or other diseases, such as psoriasis, may develop. In pediatric patients in general, outcomes do not correlate with acuity or severity. Acute erythrodermic and post-infectious PRP carry the most optimistic prognosis. These cases typically resolve without complication but resolution may be delayed for months despite treatment, and the disease may recur.45,46 The prognosis of circumscribed PRP is unclear, but it does not tend to progress or transition into other forms. Atypical juvenile PRP, including familial cases, runs a chronic course with little or no tendency to remit.33

Treatment

Topical therapy is preferable in neonates and infants though responses are inconsistent. Topical anti-inflammatory options ideally delivered in oil or ointment vehicles include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D analogs, and tar derivatives (LCD). Keratolytics such as urea and alpha-hydroxy acid may be helpful for thick scale. Topical retinoids may work but can irritate the skin. Topical salicylic acid should be avoided in infants because of the risk of salicylism. Bland emollients serve as adjunctive therapy to maintain the barrier.

In cases of extensive erythroderma, supportive care including attention to fluid and electrolyte balance and monitoring for cutaneous infection is a fundamental aspect of management. In addition to topical therapies, systemic medications may be warranted in severe, rapidly progressive or chronic and refractory cases. Oral retinoids (isotretinoin, acitretin) have the best outcome data in children and may clear the disease in weeks to months.35,36,47 Other systemic choices include oral vitamin A, cyclosporine48 and methotrexate. Pruritus can be managed with oral antihistamines and secondary infection with oral antibiotics as indicated.

Narrow-band UVB phototherapy is variably effective but can be risky as some cases are exacerbated by ultraviolet light.49 Phototherapy has been used successfully for PRP in children but there are no reports of its use in neonates or infants.

Pityriasis rosea

Introduction

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a self-limited papulosquamous eruption, which has been reported in infants as young as 3 months of age.50–52 Less than 30 well-documented cases are reported in very young infants. Disease in this age group often presents atypically and is therefore likely to be misdiagnosed.51,53,54 A separate issue is pityriasis rosea in pregnant women; these cases may be associated with fetal infection with HHV-6, premature delivery, and fetal demise. The greatest fetal risk seems to be within the first 15 weeks’ gestation. Pregnant women who develop pityriasis rosea should be referred for high-risk obstetrics evaluation.55

Cutaneous findings

Classically, but not invariably, the onset of the disease is ‘heralded’ by a single round or ovoid flesh-colored or pink scaly patch of variable size (Fig. 16.14A). The patch may appear anywhere on the body and exhibit central clearing with a raised border. The herald patch is followed in days to weeks by an eruption of smaller, variably sized, macules, papules and scaly patches (Fig. 16.14B). Four main distributions have been described in children: central (face and trunk), peripheral (arms and legs), inverse (axillary and inguinal) and diffuse.56 Lesions on the trunk arise within Langer’s skin cleavage lines and impart the appearance of a ‘Christmas tree’ pattern.57 Individual patches are often annular with a pink to tan center of fine scales and a peripheral collarette of inward pointing scale. Oral lesions may be present. The eruption evolves for several weeks and occasionally several months before spontaneously healing. The disease recurs in approximately 2% of patients.52,58

The full spectrum of cutaneous presentations in infants is as-yet unknown. A papular variant appears to be most common in infants. Other atypical morphologies include micropapular and vesicular. Unusual distributions comprise facial, inverse, localized, unilateral, or acral involvement. Infants, toddlers, and black patients are more likely to have unconventional presentations (Fig. 16.15![]() ). Post-inflammatory pigment alteration may be observed for weeks to months after resolution of the eruption.54,59,60 Infants affected with PR may have signs of an upper respiratory or other viral illness such as irritability, poor feeding, low-grade fever and lymphadenopathy preceding or during the eruption.

). Post-inflammatory pigment alteration may be observed for weeks to months after resolution of the eruption.54,59,60 Infants affected with PR may have signs of an upper respiratory or other viral illness such as irritability, poor feeding, low-grade fever and lymphadenopathy preceding or during the eruption.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Pityriasis rosea occurs worldwide without racial or sex predilection. The cause of PR remains unknown. Clinically and epidemiologically, PR best resembles an infectious disease. PR occurs throughout the year, but seasonal clustering of cases in cooler months and among social contacts together with rarity of recurrence supports an infectious etiology.58,59,61,62 Several infectious agents have been suggested; recently the role of human herpes virus (HHV)-6 and HHV-7 is being explored.63

Diagnosis of PR is based on history and clinical examination. A skin biopsy may rarely be needed to rule out alternative diagnoses. The histopathology of PR can be suggestive but not entirely specific. Most often, a superficial perivascular dermatitis comprised of slight epidermal hyperplasia, focal spongiosis, and focal parakeratosis in mounds is seen. Papillary dermal edema and a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and occasional eosinophils may be observed. Dyskeratotic keratinocytes in the epidermis and extravasated erythrocytes in the dermis are additional helpful clues in atypical cases.53

Differential diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment

The herald patch of pityriasis rosea may be mistaken for tinea corporis, nummular dermatitis, psoriasis, neonatal lupus, or pityriasis alba. In infants, the eruption of PR must be distinguished from guttate psoriasis, nummular eczema, impetigo, secondary syphilis, neonatal lupus, urticaria, lichen planus, annular capillaritis, seborrheic dermatitis, tinea corporis, and erythema annulare centrifugum. Vesicular PR may be confused with varicella and other vesicular eruptions.

Pityriasis rosea is a self-limited disorder that typically resolves without complication in 6–8 weeks. Some cases may last several months. Treatment is primarily symptomatic, and therapy in infants is rarely necessary. Topical emollients, topical corticosteroids, systemic antihistamines, and natural sunlight may be used for symptom control. Oral erythromycin has shown benefit in children as young as 1 year, but benefit of the drug versus spontaneous remission of the disease is questionable.64

Lichenoid disorders

Pityriasis lichenoides

Pityriasis lichenoides (PL) refers to a spectrum of conditions that, to date, defies straightforward classification. It is perhaps best regarded as a reactive inflammatory disorder, but evidence of T-cell clonality and rare progression to cutaneous lymphoma support the possibility that PL represents a lymphoproliferative process. These two etiologic viewpoints are not mutually exclusive. PL is classically divided into acute and chronic forms based on both clinical and histopathological features. In practice, clinical overlap between the two forms often exists. Both pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA, or Mucha–Habermann disease) and pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) are rare in infants and exceedingly rare in newborns, with fewer than 10 cases reported in the first year of life.65–68 The incidence is higher in toddlers, school-aged children, and young adults.69,70 The primary features of PLEVA and PLC are summarized in Table 16.4![]() .

.

TABLE 16.4

Major features of PLEVA and PLC

| PLEVA | PLC | |

| Primary morphology | Erythematous papules with hemorrhagic crusting or central necrosis | Red-brown scaly papules and hypopigmented macules |

| Lesion duration | Weeks | Weeks to months |

| Residual findings | Varioliform scarring or pigment alteration | Hypopigmentation |

| Histologic features | Dense lymphocytic infiltrate, keratinocyte necrosis, extravasated erythrocytes | Sparse lymphocytic infiltrate, rare keratinocyte necrosis, minimal extravasated erythrocytes |

| Disease duration | Months to years | Months to years |

PLEVA, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta; PLC, pityriasis lichenoides chronica.

Cutaneous findings

PLEVA presents with recurrent crops of erythematous papules and papulovesicles that may be distributed on the trunk and proximal extremities, limited to just the distal extremities, or diffusely over the body (Fig. 16.16). Individual primary lesions evolve to develop central necrosis with hemorrhagic crusting and then gradually resolve over weeks, sometimes leaving post-inflammatory pigment alteration or varioliform scarring. Lesions in various stages of evolution may be seen simultaneously on a given patient.70

A severe and potentially life-threatening variant of PLEVA, sometimes called ‘febrile ulceronecrotic Mucha–Habermann disease’ or ‘PLEVA fulminans’, has rarely been reported in infants.71 A widespread eruption of crusted and necrotic papules develops over days, with progression to hemorrhagic bullae and large, painful ulcers. Oral and genital mucosal ulcers may also be seen.

PLC is characterized by recurrent crops of skin-colored, pink, red, or red-brown scaly papules distributed over the trunk and extremities. As individual lesions evolve, they may flatten and become less scaly, ultimately involuting over a period of weeks to months. Hypopigmented macules or patches are also commonly seen, both in areas of previous papules, where they likely represent post-inflammatory hypopigmentation, and at times in areas without apparent prior inflammatory papules (Fig. 16.17). Rarely, hypopigmented macules may be the primary presenting morphology in the absence of papules.65 In contrast to PLEVA, hemorrhagic crusting and necrosis are not observed in pure PLC; however, overlapping morphologies of PLC and PLEVA are common. Both PLEVA and PLC may be asymptomatic or pruritic.

Extracutaneous findings

The findings of PL are typically limited to the skin, though low-grade fever or malaise may occur. In PLEVA fulminans, high fever is characteristic and may be accompanied by bacterial superinfection leading to sepsis, oral aversion and dehydration secondary to mucosal ulceration, and laryngeal edema requiring endotracheal intubation.71

Etiology and pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of PL is poorly understood. A reaction to a foreign antigen or set of antigens may trigger infiltration of T lymphocytes into lesional skin. Candidate antigens include viral particles and other infectious agents, though symptoms of a prodromal illness are elicited only in a minority of patients. Implicated triggers have included parvovirus B19, human herpesvirus 8, Streptococcus species, and measles-mumps-rubella vaccine.65,70,72,73 In most cases, no specific trigger can be identified.

The histopathologic findings of PL include a superficial perivascular and lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate with vacuolar alteration of the basal layer. In PLEVA, there is parakeratosis, individual necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis, and extravasation of erythrocytes in the papillary dermis. The findings in PLC are similar but more subtle, with a sparser infiltrate, fewer necrotic keratinocytes, and a lesser degree of erythrocyte extravasation. Cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes are more numerous in PLEVA, while CD4+ lymphocytes and regulatory T cells are found in greater numbers in PLC.72

Some cases of PL are found to contain clonal populations of T-cells. Whether this finding suggests that PL is a primary lymphoproliferative disease with malignant potential, or instead is a reactive process with secondary clonal expansion, is a matter of continued controversy. To date, only one case of PL in an infant progressing to cutaneous lymphoma has been reported, and in that case, the time between disease onset and malignant progression was greater than 10 years.74

Differential diagnosis

The eruptive crops of crusted papules and papulovesicles of PLEVA may resemble varicella, scabies or other arthropod assaults, drug eruptions, cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis, and Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. PLEVA fulminans may resemble disseminated herpes simplex infection, meningococcemia, or Stevens–Johnson syndrome. The scaly papules and hypopigmented macules of PLC may resemble guttate psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, lichen planus, or hypopigmented mycosis fungoides. Both PLEVA and PLC may be confused with lymphomatoid papulosis, which is distinguished from PL by a smaller number of larger papulonodules, which, on biopsy, reveal large, atypical CD30+ lymphocytes.

Prognosis and treatment

The course of PL is variable, and multiple relapses are common prior to eventual disease resolution. The individual lesions of PLEVA tend to resolve spontaneously in weeks, while those of PLC resolve somewhat slower, in weeks to months. It may take anywhere from a few months to more than 10 years for PL to fully resolve.65

As the disease is self-resolving, treatment is not usually required; however, some cases of PLEVA do leave scars. Symptoms of pruritus or skin irritation can be managed with emollients, topical corticosteroids, and oral antihistamines. Oral erythromycin, administered for at least 3 months, may be effective at decreasing the duration of disease in some patients.75 Oral tetracyclines are not an option in infants due to dental side-effects. Phototherapy, though technically challenging with a young infant, may also be helpful for PL; a trial of cautious natural sunlight exposure is a cost-effective alternative.

For PLEVA fulminans, treatment is critical, as this condition may be fatal. A report of two infants with PLEVA fulminans has demonstrated the effectiveness of methotrexate combined with systemic corticosteroids for treating this condition.71

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is the prototypical lichenoid eruption, characterized by flat-topped, violaceous papules. It is primarily a disease of adults, with 10% or fewer of all cases occurring in children.76 Of these, only a small fraction occurs in infants: in one report of 87 cases of juvenile lichen planus, only nine patients were under age 2.77 Onset prior to age 5 months has not been reported.78,79

Cutaneous findings

The hallmark primary lesion of lichen planus is a pruritic, violaceous, shiny, flat-topped papule. The papules tend to be several millimeters in diameter and polygonal in shape, though they may coalesce into larger, more irregularly-shaped plaques (Fig. 16.18A–C![]() ). A fine, whitish, lacy network, known as Wickham’s striae, may be visible on the surface of some lesions and can aid diagnosis (Fig. 16.18D). Almost all cases of lichen planus reported in infants have been of a linear variant, usually along an extremity.77,78,80,81 Nail dystrophy and reticulate plaques of the oral mucosa have not been reported in infants, though these changes are sometimes observed in older children and often seen in adults. In children, sites of predilection include the extremities, especially on the flexor aspects, and the lower back.77,79,80 Because lichen planus exhibits the Koebner phenomenon (occurrence in sites of trauma), the knees and elbows may be involved in children who crawl or play on the ground. No extracutaneous findings have been reported in neonates or infants.

). A fine, whitish, lacy network, known as Wickham’s striae, may be visible on the surface of some lesions and can aid diagnosis (Fig. 16.18D). Almost all cases of lichen planus reported in infants have been of a linear variant, usually along an extremity.77,78,80,81 Nail dystrophy and reticulate plaques of the oral mucosa have not been reported in infants, though these changes are sometimes observed in older children and often seen in adults. In children, sites of predilection include the extremities, especially on the flexor aspects, and the lower back.77,79,80 Because lichen planus exhibits the Koebner phenomenon (occurrence in sites of trauma), the knees and elbows may be involved in children who crawl or play on the ground. No extracutaneous findings have been reported in neonates or infants.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of lichen planus is unknown, though it appears to involve a T-cell mediated reaction to an antigenic trigger in a susceptible host. Several cases of lichen planus in older children arising after hepatitis B vaccine have been reported, and in adults, lichen planus is sometimes associated with underlying viral hepatitis, suggesting that exposure to a viral particle may trigger the reactive process.82

The histology of lichen planus reveals a dense, band-like lymphocytic infiltrate obscuring the dermal–epidermal junction. There is compact orthokeratosis of the stratum corneum, hypergranulosis, and ‘saw-toothing’ of the rete with vacuolar alteration of the basal layer. Single necrotic keratinocytes may be seen in the epidermis or in the superficial papillary dermis.

Differential diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment

The flat-topped papules of lichen planus may resemble psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides, and flat warts. In infants with linear lichen planus, lichen striatus is the primary entity on the differential diagnosis. Compared with linear lichen planus, lichen striatus tends to arise ‘fully formed’ over a shorter period of time, more commonly follows Blaschko’s lines, and is less often pruritic. Linear psoriasis, linear porokeratosis, and epidermal nevi should also be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Lichen planus follows a subacute to chronic course, which may resolve spontaneously over a period of months to years; post-inflammatory pigment alteration is common. Resolution can be hastened, and pruritus minimized, with mid- to high-potency topical corticosteroids. Treatment for several months is often required. Systemic corticosteroids can be considered in severe disease. Oral antihistamines may be useful for controlling pruritus. Phototherapy or natural sunlight exposure may be helpful in some patients but may aggravate disease in others, so caution should be exercised.

Lichen striatus

Unlike lichen planus, lichen striatus is primarily a childhood disorder, with most cases occurring in pre school-age children.83 Numerous cases in infants have been reported.84,85

Cutaneous findings

Lichen striatus tends to develop rather acutely, over a period of days to weeks, with erythematous, tan, or skin colored papules erupting in a linear or whorled arrangement along the lines of Blaschko. The individual constituent papules may be shiny and flat-topped or may be scaly. Early in its development, lichen striatus may appear inflamed and be somewhat pruritic, but fully developed lesions tend to be bland, flesh-colored to hypopigmented, and most often asymptomatic (Fig. 16.19![]() ). As lichen striatus evolves, it often leaves behind post-inflammatory pigment alteration, most commonly hypopigmentation. Nail dystrophy, with linear longitudinal ridging and splitting of the nail plate, may be seen when lichen striatus involves a digit86 (Fig. 16.20). No extracutaneous findings have been reported.

). As lichen striatus evolves, it often leaves behind post-inflammatory pigment alteration, most commonly hypopigmentation. Nail dystrophy, with linear longitudinal ridging and splitting of the nail plate, may be seen when lichen striatus involves a digit86 (Fig. 16.20). No extracutaneous findings have been reported.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of lichen striatus is unknown, but a cytotoxic T-cell mediated reaction to a virus or other foreign antigen has been suspected. Support for a viral etiology comes from the higher incidence of disease in young children compared with adults, the occasional co-occurrence in siblings, and the tendency for seasonal clustering of cases. Lichen striatus is seen more commonly in the autumn and winter months of the northern hemisphere and the spring and summer months of the southern hemisphere.85,87 Occurrence in an infant following BCG vaccination has been reported.88

The Blaschkoid distribution suggests that only a subpopulation of keratinocytes, presumably all derived from a single embryonic precursor, are susceptible to the inflammatory reaction. These keratinocytes may display an aberrant epitope that cross-reacts with the primary triggering antigen.

The histology of lichen striatus is notable for a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate along the dermal–epidermal junction, with extension of the infiltrate down adnexal structures. Focal parakeratosis, spongiosis, and isolated necrotic keratinocytes may be seen.

Differential diagnosis

Lichen striatus should be distinguished from linear lichen planus, which tends to be more gradual in onset and more pruritic. Lichen striatus is also more likely to resolve with residual hypopigmentation, whereas linear lichen planus is more likely to resolve with hyperpigmentation. The differential diagnosis also includes epidermal nevus, particularly inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). ILVEN is usually more pruritic than lichen striatus and does not resolve spontaneously. Other entities to consider include linear psoriasis and linear porokeratosis. Incontinentia pigmenti also follows Blaschko’s lines, but typically presents in the newborn period and is usually more vesicular or verrucous.

Prognosis and treatment

Lichen striatus resolves spontaneously without intervention. The average duration is approximately 6–12 months, but some cases last considerably longer and residual hypopigmentation may persist for several years.83,87 Topical corticosteroids and emollients may be applied for pruritus, but they do not decrease the duration of disease or affect the degree of postinflammatory pigment alteration.

Lichen nitidus

Lichen nitidus is a distinctive inflammatory disorder that tends to affect children and young adults, but can affect infants. It has not yet been described in newborns.

Cutaneous findings

The primary lesion of lichen nitidus is a pinpoint, skin-colored papule with a shiny, flat-topped surface (Fig. 16.21A–D![]() ). Monomorphic papules usually occur in clusters, most frequently on the upper trunk, volar wrists, dorsal hands, and the genitalia. The central face may also be involved. A generalized variant has been described in infants.89,90 Pruritus may accompany the generalized form and sometimes the localized form, but typically the lesions are asymptomatic. Koebnerization is common. A rare photo-distributed form, called ‘lichen nitidus actinicus’, has not been reported in infants to date. Several case reports have described lichen nitidus occurring in infants with Down syndrome.90,91 Juvenile arthritis arising several months after the onset of lichen nitidus in an infant has also been described, but that association may have been coincidental.89

). Monomorphic papules usually occur in clusters, most frequently on the upper trunk, volar wrists, dorsal hands, and the genitalia. The central face may also be involved. A generalized variant has been described in infants.89,90 Pruritus may accompany the generalized form and sometimes the localized form, but typically the lesions are asymptomatic. Koebnerization is common. A rare photo-distributed form, called ‘lichen nitidus actinicus’, has not been reported in infants to date. Several case reports have described lichen nitidus occurring in infants with Down syndrome.90,91 Juvenile arthritis arising several months after the onset of lichen nitidus in an infant has also been described, but that association may have been coincidental.89

Etiology and pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of lichen nitidus is unknown. In most cases, no inciting trigger can be identified, but several reports in older children of photodistributed lichen nitidus (lichen nitidus actinicus) suggest that sun exposure may sometimes be contributory;80 this may reflect a Koebner phenomenon.

The histologic features of lichen nitidus are highly distinctive. A granulomatous collection of histiocytes and lymphocytes is seen in the papillary dermis, which is flanked on either side by elongated rete ridges, giving the appearance of a ‘ball in claw.’ There may be overlying parakeratosis and thinning of the epidermis with vacuolar alteration of the basal layer.

Differential diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment

The minute papules of lichen nitidus may resemble lichen spinulosus or keratosis pilaris, though those conditions are characterized by folliculocentric papules that usually have a central keratotic spine. Papular eczema may resemble generalized lichen nitidus, but the papules of lichen nitidus tend to be more discrete. Other entities on the differential diagnosis include micropapular lichen planus, flat warts, and an id reaction.

Lichen nitidus tends to resolve spontaneously over years. Treatment is rarely indicated, though in patients with pruritus, topical corticosteroids, emollients, oral antihistamines, and phototherapy may be of benefit.

Keratosis lichenoides chronica

Keratosis lichenoides chronica (KLC) is a rare, chronic disorder with histologic features similar to lichen planus but with unique morphologic characteristics. Some early reports of lichen planus in infants may, in retrospect, have described what would now be considered KLC.92,93

KLC has recently been delineated into juvenile and adult forms.94 The juvenile form, which often begins in the newborn period or within the first year of life, tends to show sparing of the nails and mucosal surfaces, alopecia of the upper face, and occasional involvement of sibling pairs. By contrast, in the adult form, the nails and mucosa are often involved, alopecia is not associated, and the disease tends to occur in a sporadic fashion.

Cutaneous findings

In infants, lesions of KLC tend to appear first on the face.94 Facial lesions favor the cheeks, chin, and ears, where a variety of morphologies may be seen: well-demarcated erythematous plaques with seborrhea-like scale, polycyclic erythematous plaques with an accentuated border, or purpuric patches, all of which may evolve to leave hyperpigmentation.94–96 Alopecia of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and forehead may be observed.94 On the extensor extremities and buttocks, hyperkeratotic, erythematous to violaceous papules develop, which coalesce to form linear or reticulated plaques. The lesions of KLC may be pruritic but are often asymptomatic. No extracutaneous findings have been reported in infants.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of KLC is unknown. The histologic features of KLC resemble those seen in lichen planus, with a dense band-like lymphocytic infiltrate along the dermal–epidermal junction, vacuolar alteration of the basal layer, irregular acanthosis of the epidermis, hyperkeratosis, and focal parakeratosis.

Differential diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment

The facial lesions of KLC may resemble seborrheic dermatitis or lupus erythematosus. Lichen planus may also present with hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on the extremities, but the linear configuration and resistance to treatment of KLC are relatively specific features.

KLC is a progressive disorder that evolves over years to decades. Phototherapy may produce modest improvements, but no treatments have consistently shown efficacy in controlling this condition.97 Systemic retinoids are a therapeutic option in older children with severe disease but have not been reported in infants.

Access the full reference list at ExpertConsult.com ![]()

Figures 4, 5, 7, 12, 15, 18A, B, 19 and 21A, C are available online at ExpertConsult.com ![]()

Tables 2, 3 and 4, are available online at ExpertConsult.com ![]()