Chapter 19 Panniculitis

Table 19-1. Major Forms of Panniculitis

| Septal Panniculitis

Lobular and Mixed Panniculitis Metabolic Derangements |

Infectious Panniculitis

Malignancy

Other Changes of the Fat

Lipodystrophy

Lipoatrophy

Lipohypertrophy

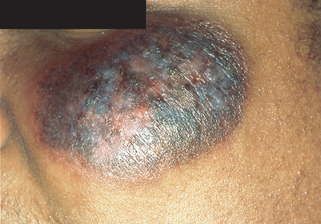

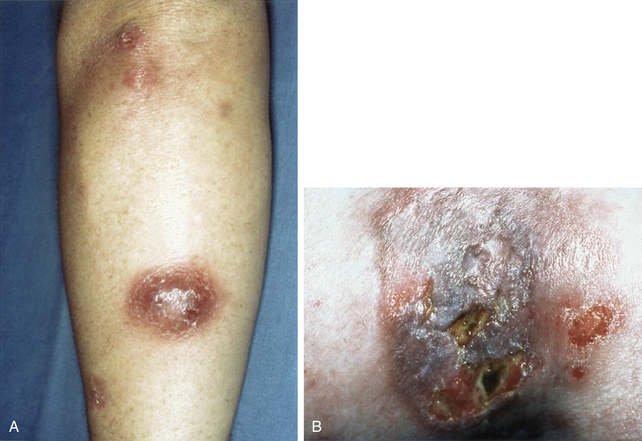

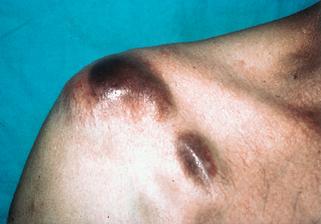

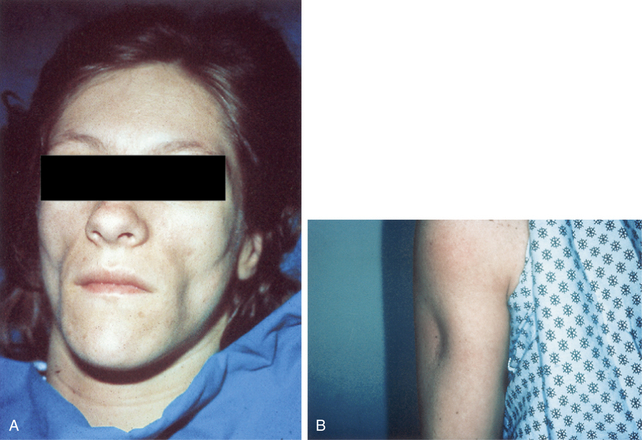

Figure 19-3. Erythema induratum demonstrating characteristic indurated subcutaneous nodules. Spontaneous ulceration is common.

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)

Key Points: Panniculitis

Key Points: Erythema Nodosum

Key Points: Lupus Panniculitis

Mascaró JM Jr, Baselga E: Erythema induratum of Bazin, Dermatol Clin 26:439–445, 2008.

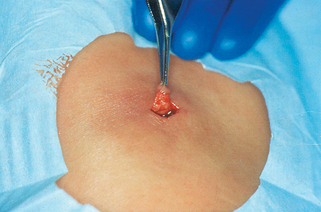

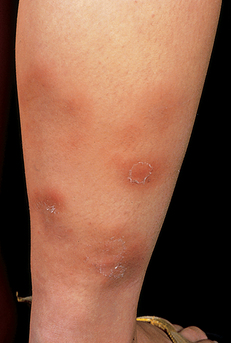

Figure 19-7. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis showing foci of hemorrhage in the center of the lesion.

(Courtesy of Kenneth E. Greer, MD.)

Chowdhury MM, Williams EJ, Morris JS, et al: Severe panniculitis caused by ZZ alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency treated successfully with human purified enzyme (Prolastin), Br J Dermatol 147:1258–1261, 2004.

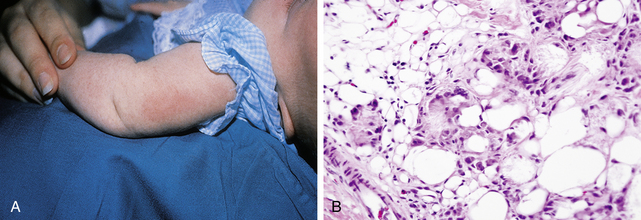

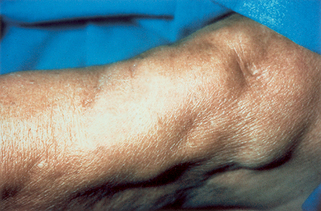

Figure 19-8. Sclerosing panniculitis with lipoatrophy caused by repeated injection of pentazocine.

(Courtesy of Kenneth E. Greer, MD.)