Chapter 27 Panniculectomy in patients with super obesity

• Strict indication for patient selection according to the Igwe Grades 4–5.

• Panniculectomy should be considered as a combined procedure together with the bariatric surgeon.

• Use patient lifts for assistance.

• Minimal undermining to prevent dead space and seroma.

• No muscle plication in order not to increase intraabdominal pressure.

• Perioperative management should comprise forced diuresis and early ambulation.

Introduction

There are numerous conservative and operative strategies for the treatment of obesity. Plastic surgeons are increasingly confronted with the need for body contouring after massive weight loss through dietetic methods or bariatric surgery.1–5

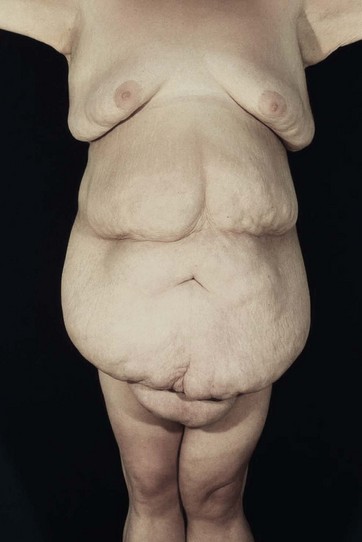

Patients with marked pannus usually have, in addition to significant medical comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome and premature arthritis, massive problems of hygiene in the lower abdominal fold, with recurrent furuncles, abscesses, and fistulas. In addition, distinct functional problems exist such as immobility, with the development of secondary lymphedema, chronic ulceration on the extremities, and pressure sores. Some patients with high body mass index show severe elephantiasis in the entire abdominal wall. Quite often there are additional problems in micturition, especially in male patients whose genitalia are completely obstructed6 (Fig. 27.1).

Historically, panniculectomy was done only in selected cases, when there was complete immobility, or patients were not suitable for bariatric surgery. The aim of such intervention was to interrupt the vicious circle of lack of mobility and insufficient calorie consumption. This was usually followed by a successful conservative weight reduction or bariatric surgery.11–15

Today, such procedures are often performed together with bariatric surgery.5–7 The plastic surgeon performs the panniculectomy, thus the general surgeon gains access to the abdominal wall and then laparoscopically places the gastric banding or performs a gastric bypass or sleeve.

The subsequent weight loss leads to an immediate increase in mobility. If the process of losing weight is completed and there is weight maintenance of about 1 year, subsequent plastic-reconstructive surgical operations are possible to complete the surgical treatment.8

Preoperative Preparation

Patients eligible for panniculectomy should be chosen carefully. Operations on such a patient population are always risky, since metabolic syndrome and the long-lasting cardiovascular stress tend to result in severe complications. Besides the increased general risks, however, there exist significantly increased surgical complication rates, with increased blood loss, excessive seroma formation, wound healing problems and necrosis. In the few publications related to this issue, complication rates are more than 50%; even serious events stated to be 2.5% seem not be substantially increased. Blood loss is given in the literature as significant (from 800 to 2500 ml with decrease of hemoglobin and a consequent transfusion requirement in more than 20%). Hernias were found in about 20% of patients and were treated mostly within the same session. The infection rate given in the literature is on average about 15%, due to poor preoperative hygiene.9–11

Regarding the case history it is important to find out how many serious attempts to diet have been undertaken and whether there are exclusion criteria for bariatric surgery. The normal course of the survey includes, first of all, a classification of the pannus in the degree classification according to Igwe:12

• Grade one: coverage of the pubic hair (Fig. 27.2)

• Grade two: coverage of the mons pubis (Fig. 27.3)

• Grade three: coverage of the upper third of the thigh (Fig. 27.4)

• Grade four: coverage of the top half of the thigh (Fig. 27.5)

In addition to this classification the presence of a permanent lymphedema of the abdominal wall (elephantiasis) needs to be documented. In this case it is called a pannus morbidus and recurrence after abdominal amputation in later courses of surgery is almost certain (Fig. 27.7).

Furthermore, we look for secondary lymphedema in the extremities; carefully inspecting the abdominal fold, the umbilical region, and the external genitalia, especially for intertriginous inflammation, boils, or abscesses. The abdomen is carefully examined in the supine and standing positions for clinical hernia. In particular, the umbilical region is a predilection site. An exploratory ultrasound of the abdomen should be mandatory, because the clinical examination is often difficult. In most cases, we also request a CT scan of the entire abdomen for safe exclusion of a hernia, and a Doppler ultrasound of the deep venous system for the safe exclusion of thrombosis.13

Surgical Technique

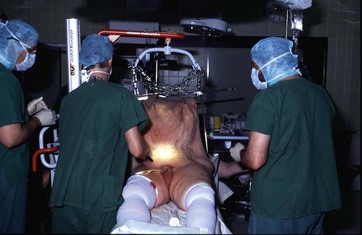

Immediately after the initiation of anesthesia the pannus is to be lifted (Fig. 27.8). To facilitate this procedure two to three conventional meat hooks are placed after stitch incisions at the apex of the abdominal wall (Fig. 27.9). Then, a patient lift, such as that found on most intensive care units, is pushed through the abdominal wall and iron chains suspended from the meat hooks. Slowly, and with continuous monitoring of the central venous pressure, the pannus is now lifted. This maneuver is carried out slowly, as there may be a significant relevant effect on the circulation due to interstitial and intravascular fluids. It follows an improvement in breathing resistance and a return blood flow in the sense of an autotransfusion (Fig. 27.10).11,14,15

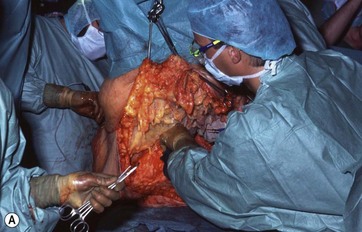

When the maximum height is reached the base of the area to be excised is infiltrated with tumescent solution to allow the most anemic preparation. Now the abdominal fold is meticulously disinfected and the bladder catheter is placed. Then the lifting crane is slightly released, so that the resection marks can be checked once more for tension-free closure. Afterwards the abdomen is scrubbed and sterile draped. The resection usually starts with two surgeons working in parallel. By using a Colorado needle for the incision it should be ensured that the lower incision is made strictly at 90° to the abdominal wall, so that no high tension on the skin occurs later. This follows the preparation to the upper resection marks, preserving Scarpa’s fascia in order to avoid seroma (Fig. 27.11). To prevent heat development and seroma we use an ultrasound cutting device, which shows significantly less fluid collection postoperatively.16 We avoid further preparation to prevent any unnecessary cavitation. In general, the umbilicus is resected, as an umbilical transposition would require further preparation that in turn would increase the likelihood of further cavitation. The voluminous periumbilical veins are either clipped or ligated.

In this region the surgeon has to watch out for hernias as they can occultly occur around the navel (Fig. 27.12).

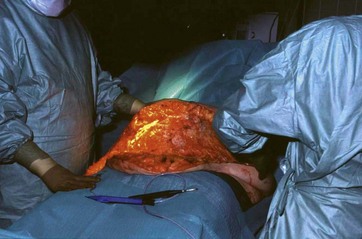

Then the pannus is cut off and weighed. In the upper section of the incision line a 90° angle is essential in order to achieve good adaptation to the lower cut line (Fig. 27.13).

Finally, the entire wound is again checked for bleeding and rinsed carefully and thoroughly with sodium chloride. The wound is closed in multiple layers, and multiple Baroudi sutures are applied to reduce the cavities. In particular, Scarpa’s fascia is adapted exactly to minimize the tension of the skin. We insert multiple drains and plug them in a vacuum pump with continuous pressure. The closure of the skin is done atraumatically intracutaneously, with additional application of PRINEO-topical skin adhesive to prevent local wound infections (Fig. 27.14).

Case studies are shown in Figs 27.15–27.22.

FIG. 27.19 Elevating the abdominal pannus and the mons pubis, demonstrating the hidden penis and scrotum.

Optimizing Outcomes

Most complications can be attributed to wound fluid retention. Therefore, the prevention of fluid loss has highest priority. We showed in an evidence-based study level I that the use of an ultrasonic scalpel results in less blood loss and lower seroma rates.16 Furthermore, a preparation preserving Scarpa’s fascia has also the advantage of not damaging the underlying lymphatic network. Thus less seroma occurs. The insertion of drains in abdominoplasty is also evidence based. In this case we insert multiple drains and connect them to a continuous vacuum system. The significant advantage is that not only are the liquids aspirated, but a continuous negative pressure causes the wound surfaces to stick together more effectively. The use of Baroudi sutures is also evidence based and leads to a reduction of the cavities, as well as progressive tension sutures, which reduce the tension of the wound surface.

Studies have not yet shown a significant reduction of seroma using fibrin glue.

The operation time plays an important role in respect of the complication rate. Usually two surgeons operate simultaneously, so that the operation time does not exceed 90 minutes (Fig. 27.23).

1 Petty P, Manson PN, Black R, et al. Panniculus morbidus. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;28:442.

2 Hanna D, Cloutier R, Lapointe R, et al. Abdominal elephantiasis: A case report. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:229.

3 Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238.

4 Hopkins MP, Shriner AM, Parker MG, et al. Panniculectomy at the time of gynecologic surgery in morbidly obese patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1502.

5 Igwe D, Jr., Stanczyk M, Lee H, et al. Panniculectomy adjuvant to obesity surgery. Obes Surg. 2000;10:530.

6 Haritopoulos KN, Labruzzo C, Papalois VE, et al. Abdominoplasty in a patient with severe obesity. Int Surg. 2002;87:15.

7 Acarturk TO, Wachtman G, Heil B, et al. Panniculectomy as an adjuvant to bariatric surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;53:360.

8 Kenkel J. Body contouring surgery after massive weight loss. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1S.

9 Friedrich JB, Petrov RV, Askay SA, et al. Resection of panniculus morbidus: a salvage procedure with a steep learning curve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:108.

10 Vastine VL, Morgan RF, Williams GS, et al. Wound complications of abdominoplasty in obese patients. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42:34.

11 Venturi ML, Attinger CE, Mesbahi AN, et al. Mechanisms and clinical applications of the vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) device: A review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:185.

12 Igwe D, Stanczyk M, Lee H, et al. Panniculectomy adjuvant to obesity surgery. Obes Surg. 2000;10:530.

13 Hughes KC, Weider L, Fischer J, et al. Ventral hernia repair with simultaneous panniculectomy. Am Surg. 1996;62:678.

14 Richard EF. A mechanical aid for abdominal panniculectomy. Br J Plast Surg. 1965;18:336.

15 Jensen PL, Sanger JR, Matloub HS, et al. Use of a portable floor crane as an aid to resection of the massive panniculus. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;25:234.

16 Stoff A, Reichenberger MA, Richter DF. Comparing the ultrasonically activated scalpel (harmonic) with high-frequency electrocautery for postoperative serous drainage in massive weight loss surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(4):1092–1093.

Belin RP, Stone NH, Fischer RP, et al. Improved technique of panniculectomy. Surgery. 1966;59:222.

Jackson JA, Steeper JR. Operative incision of giant panniculus adiposus. J Int Coll Surg. 1951;15:85.

Jones LJ, Boines GJ. Rehabilitation in the obese by lipectomy. Del Med J. 1946;18:161.

Kelly HA. Excision of the fat of the abdominal wall-lipectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1910;10:229.

Kelly HA. Report of gynecological cases. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1899;10:197.

Larkin CL. Lipectomy for abdominal fat. Conn Med J. 1950;14:706.

Matory WE, Jr., O’Sullivan J, Fudem G, et al. Abdominal surgery in patients with severe morbid obesity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:976.

Meyerowitz BR, Gruber RP, Laub DR. Massive abdominal panniculectomy. JAMA. 1973;225:408.

Smith L. Excision of panniculus adiposus. J Med Assoc Ga. 1939;28:193.