Chapter 50 Pancreatic Duct Leaks and Pseudocysts

Introduction

The initial manifestations of acute pancreatitis are caused for the most part by local enzyme activation and acute cytokine release. This combination leads to local pain, ileus, peripancreatic burn, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and early organ failure including acute respiratory distress syndrome. Perpetuation of the disease process may be a consequence of infection of necrotic tissue or ongoing ductal leak.1–4 Chronic pancreatitis may also result in a pancreatic duct leak or fistula, as may trauma, surgical or otherwise.1,5 In chronic pancreatitis, the consequence of the leak depends on the etiology, the size of the ductal disruption, the location of the leak relative to anatomic tissue planes, and the body’s success in walling off and containing the disruption. In traumatic pancreatitis, there is usually a smoldering acute inflammatory response and an acute leak. This combination can result in a seriously ill patient after penetrating trauma or a patient who remains clinically well after surgical drain placement at the time of splenectomy and inadvertent damage to the pancreatic tail.6

Pancreatic duct leaks or fistulas have traditionally been defined as internal or external.3,7 External leaks (pancreaticocutaneous fistulas) almost always follow percutaneous drainage of internal pancreatic fluid collections or pancreatic surgery. Less commonly, they are the consequence of penetrating abdominal trauma. Internal pancreatic fistulas include pancreaticoenteric fistulas, pseudocysts, pancreatic ascites, and pancreatic pleural effusions.4,8 Pancreatic necrosis, which is clearly associated with ductal disruption in three-fourths of patients, has not traditionally been defined as the cause or consequence of a pancreatic fistula.9–11 Box 50.1 summarizes the current classification of pancreatic fistulas.

Epidemiology

The incidence of pancreatic duct leaks is uncertain and seems to be independent of the cause of the underlying pancreatitis. Whether caused by alcohol, biliary tract disease, metabolic disorders, or medications, an acute leak seems to be related more to disease severity. Multiple reports suggest that 30% to 75% of pancreatic necrosis is associated with ductal disruption, although there is considerable debate whether this disruption is a primary or secondary phenomenon.7,9,10,12 Also, 40% of patients with acute pancreatitis may develop some peripancreatic fluid collection, although less than 5% of these patients develop a true pseudocyst, and a much smaller percentage have decompression of these fluid collections by formation of a pancreaticoenteric fistula.13 Chronic pancreatitis predisposes not only to pseudocyst formation but also to pancreatic ascites and high-amylase pleural effusions. High-amylase pleural effusions are chronic and have a distinctly different chemical composition and pathophysiology than the more common acute pleural effusions noted in the setting of severe acute pancreatitis.3,7

Pathogenesis

Pancreatic duct leaks are the consequence of enzyme activation with subsequent necrosis of ductal epithelium, the result of increased intraductal pressure often behind a stricture or stone or both.3,7 Alternatively, leaks may be caused or perpetuated by percutaneous drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections; surgical resection or bypass; tumor disruption of ductal epithelia; or pancreatic trauma, particularly penetrating trauma.14–25 Box 50.2 lists some etiologies of pancreatic duct leaks.

Clinical Features

The clinical features of pancreatic duct leaks depend on the cause of the disruption and its size and site. Pancreatic juice follows tissue planes, and the body is variably successful in containing this leak contingent on such factors as rate of leak and presence or absence of superinfection. Superinfection, early cytokine release, bacterial translocation from the gut, endotoxin release, and extraluminal enzyme activation also determine many of the clinical features associated with acute pancreatitis, such as pain, ileus, nausea and vomiting, tachycardia, oliguria, and hypotension.26,27 From an anatomic standpoint, a leak may be low grade and stay within the confines of the parenchyma leading to smoldering pancreatitis or variable degrees of necrosis, the latter often associated with multisystem organ failure and local and systemic infections.7,28–32 Necrosis may also lead to internal fistulization into contiguous organs including the C-loop most commonly but also the bile duct, stomach, transverse colon, or jejunum.3,33–36

Depending on the degree of leak and its perpetuation by necrosis or downstream ductal obstruction and ongoing oral feeding and pancreatic stimulation, head leaks often are associated with right pararenal fluid collections and can track along the psoas musculature to cause pelvic fluid collections that can track into the scrotum or buttocks.36 If volumes of juice are sufficient, with resultant pancreatic ascites, I have even seen prolapsed and ulcerated vaginal vaults and uteri because of increased intraabdominal pressure. Pancreatic head leak that is successfully walled off by the body may cause a pseudocyst localized to the right upper quadrant. Although the latter may be asymptomatic, if small, common presentations of larger pseudocysts in this location include postprandial or chronic pain, early satiety or postprandial nausea and vomiting from variable degrees of gastric outlet obstruction, or biliary obstruction. Biliary obstruction may cause jaundice or occasional cholangitis but is more often associated with liver function abnormalities including variable elevations of transaminases and alkaline phosphatase.

Leaks of the pancreatic duct tail have been associated with left upper quadrant or perisplenic pseudocysts,3,37 if contained and walled off. Alternatively, they may track into the retroperitoneum and cause high-amylase pleural effusions22,38–40 or acute pararenal or pelvic fluid collections. Fistulization into the ligament of Treitz or the transverse colon or splenic flexure also is occasionally seen but almost exclusively in the setting of active necrosis.15,34,41 Depending on the rapidity of the leak and the presence or absence of concomitant necrosis, clinical signs and symptoms of a tail leak may include shortness of breath, nausea and postprandial pain, or clinical signs of sepsis because of a pancreaticocolonic fistula.

Leaks that occur from the genu to the distal body or proximal tail area of the pancreas occur most commonly in the setting of necrosis and result in lesser sac fluid collections.3,14,42–46 Traditionally defined as pseudocysts, these fluid collections are usually more complex, containing considerable saponified fat and tissue debris. The consistency and viscosity of lesser sac fluid collections are routinely misinterpreted by abdominal computed tomography (CT), often leading to therapeutic misadventures with attempts to drain these collections radiographically, endoscopically, or surgically.4,11,19,47–50 To distinguish these collections from more traditional pseudocysts that can have a similar imaging appearance, Baron and colleagues50 termed these latter collections evolving pancreatic necrosis, a variant of walled-off pancreatic necrosis, and suggested that the patient’s clinical course may be more important than traditional abdominal imaging.

The lesser sac is also often a decompressive site for patients with chronic pancreatitis with downstream duct obstruction from a pancreatic stone or stricture. This condition can result in a variably sized pseudocyst or pancreatic pericardial effusion if there is mediastinal involvement. Additional chest manifestations include pancreatic pleural effusion, as noted previously, and pericardial tamponade or pancreaticobronchial fistulas.3,31 Central pancreatic leaks are usually the cause of pancreatic ascites also.7,22,39,51 Associated with a concomitant and leaking pseudocyst in 50% of patients, clinical presentation may include increased pain plus abdominal girth, shortness of breath from diaphragmatic compression or concomitant pleural effusions, and occasional spontaneous bacterial peritonitis from bacterial translocation from the gut.

Pathology

Because of the variability of etiology of ductal disruptions, there is no one all-encompassing pathology. Instead, chronic pancreatitis is usually associated with the formation of a leak and its myriad manifestations (pseudocyst, ascites, and pancreatic pleural effusions) by virtue of ductal obstruction by an inflammatory stricture or intraductal calcification.3,8 In such settings, acute parenchymal inflammation may be negligible. In contrast, the acute inflammatory response seen in acute pancreatitis, particularly pancreatic necrosis, has been claimed by some authors to be the primary event with subsequent lysis of ductal epithelial cells resulting in a leak.52 There is likely a mixture of scenarios in either setting with the resultant pathology depending on the site and size of the disruption; the presence or absence of activated enzymes; and the body’s success at walling off the leak, initially with inflammatory cells but later with formation and organization of collagen. The last-mentioned is perhaps best represented by a pseudocyst that can be broken down further into acute pseudocyst (collection of pancreatic juice enclosed by a wall of nonepithelialized granulation tissue that arises as a consequence of acute pancreatitis, requires at least 4 weeks to form, and is devoid of significant solid debris) and chronic pseudocyst (a collection of pancreatic juice enclosed by a wall of fibrous or granulation tissue that arises as a consequence of chronic pancreatitis).23,50

Differential Diagnosis

The etiology and the benign nature of most pancreatic duct leaks are easy to confirm if one considers the diagnosis in the first place because of access to excellent abdominal imaging through ultrasound, CT scanning, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging including secretin-magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (S-MRCP), and endoscopic modalities such as endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).3,13,23,53–57 Routine aspiration of ascites or pleural effusions for amylase and lipase usually confirms a pancreatic etiology, and a fluid collection in the left upper quadrant after a splenectomy, left nephrectomy, or complicated antireflux procedure can be confirmed as pancreatic in origin if one thinks to check an amylase level at the time of diagnostic percutaneous aspiration or therapeutic drain placement. In these instances, inadvertent damage to the tail of the pancreas is substantially more common than local perforation of the stomach or splenic flexure of the colon at the time of surgery.

In addition, the diagnosis of a pancreatic duct leak should not be difficult in patients with a persistent fluid output after a pancreatic resection or percutaneous drainage of an acute, amylase-rich fluid collection in the setting of acute or chronic pancreatitis. The major differential diagnostic dilemma occurs in patients without a known history of pancreatitis who present with what appears to be a pseudocyst. There have been multiple approaches to distinguish pseudocysts from cystic neoplasms and benign from potentially malignant cystic tumors. Ultrasound and CT characteristics favoring pseudocyst include parenchymal or ductal calcifications, a uniform appearance to the cyst, and lack of calcifications in the lesion itself. Cysts that show an irregular wall thickness with mass effect, septations, or punctate wall calcification are more likely to be neoplastic. Cyst aspiration for amylase, mucus, carcinoembryonic antigen level, and cytology can be done under CT, ultrasound, or EUS guidance and has been used to distinguish benign and malignant neoplastic cysts from pseudocysts.58 Pseudocysts are discussed in detail in other chapters.

As noted previously, S-MRCP has occasionally been used to document a pancreatic duct leak, particularly in the setting of pancreatic necrosis.53 ERCP has been used more commonly not only to diagnose but also to treat pancreatic duct leaks. Leaks may be demonstrable by abnormal flow of contrast material into a pseudocyst, into the peritoneal or thoracic cavity, or into the bile duct or a contiguous loop of bowel in the setting of internal fistulas.1,3,7 Alternatively, contrast material can often be seen flowing into a surgically or radiologically placed Jackson-Pratt drain in external fistulas.5,22,36,59 In the setting of central pancreatic necrosis or severe chronic pancreatitis, ERCP may simply document a complete obstruction of the main pancreatic duct. In this setting, the leak occurs upstream from the obstruction or from a disconnected portion of the gland—the disconnected duct syndrome. Box 50.3 summarizes some diagnostic tests available for pancreatic duct leaks.

Treatment

Therapy for pancreatic duct leaks does not occur in an endoscopic vacuum. Strategies include preventing a leak in the first place, using good surgical technique, and possibly using intraoperative fibrin glue or stent placement or postoperative octreotide after partial pancreatectomy or decompressive pancreatic surgery.5,60–64 The ability to place a transpapillary stent does not mean that this modality is suitable for all patients. Individuals with leaks are best approached by a team consisting of an interventional radiologist, a pancreaticobiliary surgeon, and an endoscopist capable of performing both diagnosis and therapy (Box 50.4).1,3,65

Pseudocysts

Pseudocysts were historically treated surgically, usually by cyst-enteric or cyst-gastric anastomoses, although pancreatic resection has occasionally been used for pseudocysts in the pancreatic tail.25,66–69 Likewise, complex cysts with significant internal septations or debris have been treated with external drainage. Morbidity and 30-day mortality rates for open surgery have approximated 25% to 30% and 2% to 5% with recurrence rates of 10% to 20%.25,57,69,70 These statistics have led some centers to approach surgical decompression laparoscopically and to insist on preoperative MRCP or ERCP to delineate better the ductal anatomy as a guide to type of surgery (decompression vs. resection).25,56,71,72 No randomized trials have compared surgical with nonsurgical management of pseudocysts; instead, retrospective reviews are available in which 30 patients with pseudocysts were treated with surgery (49%), endoscopy (39%), or percutaneously (11%). There were no differences in pseudocyst resolution or complications in patients treated surgically or endoscopically.73

A series by Melman and colleagues66 defined higher initial success rates for laparoscopic versus open pseudocyst drainage, although comparable success rates were noted with endoscopic, radiologic, or salvage surgical drainage. In many centers, percutaneous drainage of pseudocysts with long-term catheter placement has become the standard of care by which other treatment modalities have been judged. Individual series and meta-analyses of the literature suggest 85% successful resolution rates, although catheter occlusions with subsequent bacterial seeding and iatrogenic infection with need for urgent catheter exchange remain problematic particularly if the cyst is filled with debris.7,36,74 In addition, in individuals who develop a disconnected gland syndrome from trauma or necrosis, placement of a percutaneous drain may result in a chronic pancreatic external fistula that may necessitate Jackson-Pratt drainage for months or years. Alternatively, percutaneous injection of glue or fibrin has been used in an attempt to close the fistulous tract, and surgery may be required to resect the distal (tail), disconnected portion of the gland.75

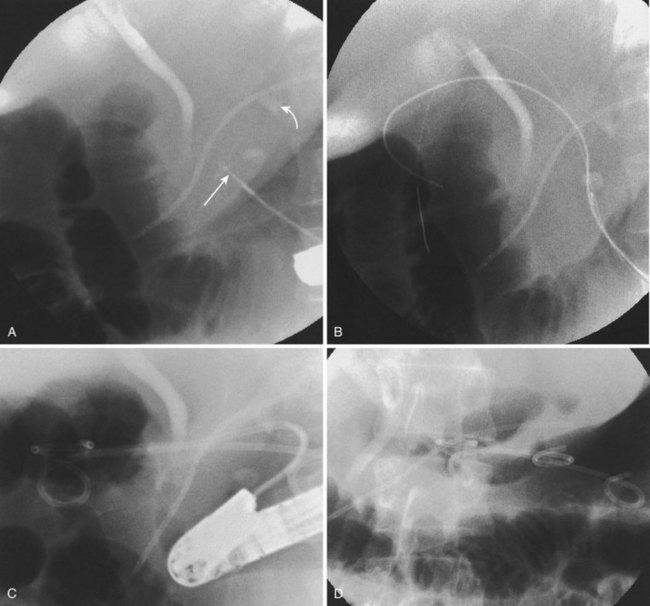

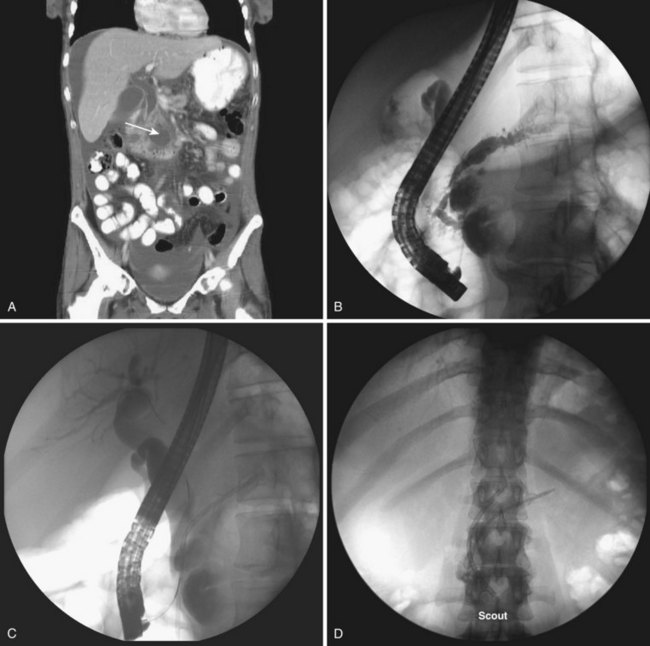

Endoscopic pseudocyst drainage was first described by Rogers and coworkers76 in 1978 using a needle placement through the gut wall to drain a pseudocyst that rapidly recurred. The first successful electrocautery fistulization into a pseudocyst was done more than 2 decades ago and resulted in permanent cure in three of the first four patients in whom it was undertaken.77 Although the procedure has been refined to take advantage of abdominal CT, EUS, and MR imaging and MRCP, large pseudocysts still require some form of access, either by needle-knife sphincterotome or transgastric or transenteric injection with a Seldinger needle followed by placement of one or more guidewires into the cavity proper (Fig. 50.1).78–97 Historically, the incisions were enlarged using some form of electrocautery (conventional or needle-knife sphincterotomy or an overtube that conducted cautery), but 6- to 10-mm hydrostatic balloons are used in most cases at the present time to enlarge the communication to the stomach or duodenum. A variation of this procedure is use of a transluminal balloon accessotome.98 Although various stents have been used to maintain the fistulous communication between the gut and pseudocyst, most endoscopists currently use 7-Fr to 10-Fr double-pigtail stents to minimize migration, leaving them in place for 6 to 8 weeks or until abdominal imaging has confirmed pseudocyst resolution.

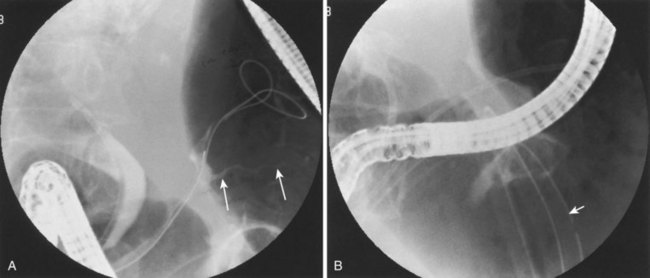

Although the need for preprocedure antibiotics has not changed, other things have. With the advent of therapeutic EUS scopes, it is no longer necessary to see a “bulge” on the stomach or duodenal wall to ensure that one is entering the fluid collection.83,89–91,94,95,99–102 Therapeutic duodenoscopes are not required; concomitant ERCP is usually employed to define ductal anatomy including the presence of an ongoing leak or disconnected duct and gland syndrome.1,7 A leak can be treated with transpapillary stents (Fig. 50.2) allowing resolution of small pseudocysts without need for concomitant drainage102; disconnected duct and gland syndrome can signal the need for ultimate surgery or long-term indwelling pseudocyst stents in patients who are a very poor surgical risk.103

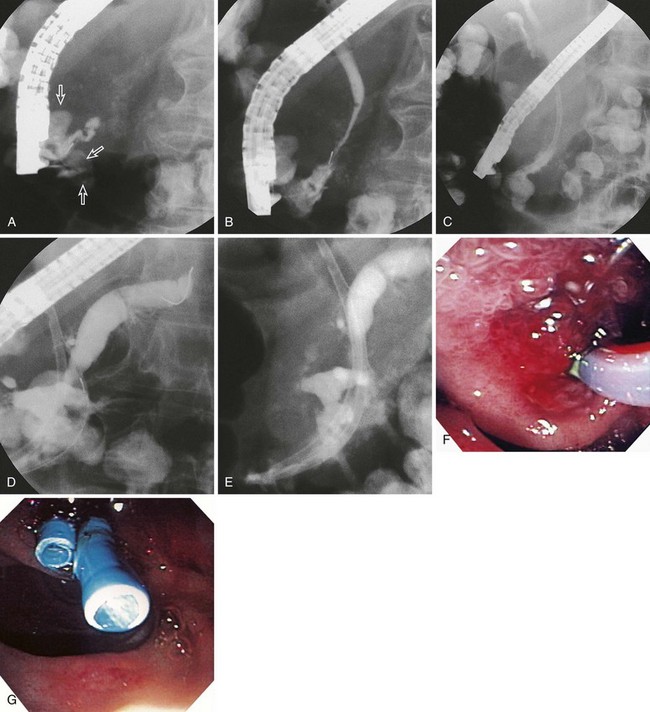

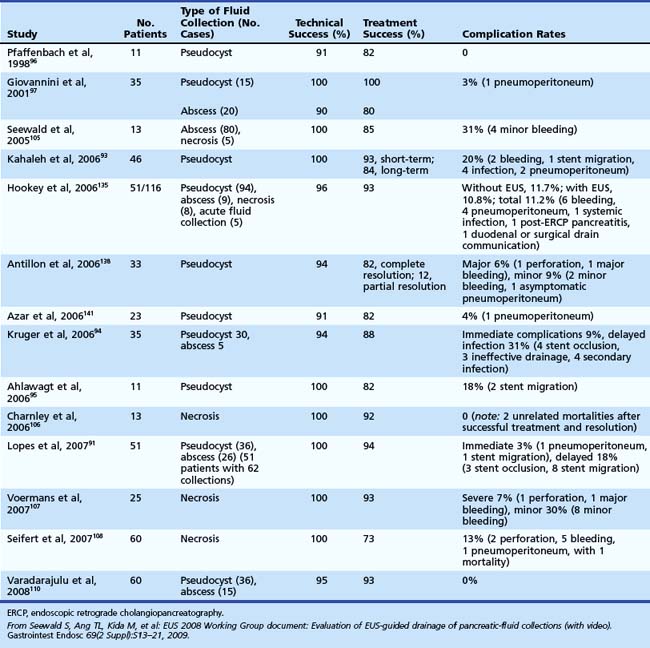

Many case reports or series have described transpapillary stents or transenteric or transgastric fistulization into pseudocysts with their attendant resolution; however, one of the better ones has been by Baron and colleagues.50 These authors looked at endoscopic drainage techniques and outcomes in acute versus chronic pseudocysts and in pancreatic necrosis. Historically, endoscopic attempts at drainage of necrosis were fraught with bleeding and infectious complications because of increased vascularity at the necrosis–viable tissue interface and because it has proven difficult to drain extremely thick and viscous debris through small-diameter, endoscopically placed stents. Baron and colleagues50 instead placed nasocystic tubes and performed irrigation with large-volume saline for prolonged periods (3 to 6 weeks) of irrigation in an attempt to break up the necrotic debris and flush it into the lumen of the gut. Ultimately, they achieved complete resolution of the various pancreatic fluid collections in 113 of 138 (82%) patients, although resolution was more frequent in patients with chronic pseudocyst (59 of 64 [92%]) than in patients with acute pseudocyst (23 of 31 [74%]; P = .02) or pancreatic necrosis (31 of 43 [72%]; P = .006). In addition, complications were more common in patients with necrosis who had endoscopic drainage (16 of 43 [37%]) than patients with acute pseudocysts (6 of 31 [19%]; P = not significant) or chronic pseudocysts (11 of 64 [17%]; P = .02). At a median follow-up of 2.1 years, recurrent fluid collections were more common in patients with necrosis (9 of 31 [29%]) than patients with acute pseudocysts (2 of 23 [9%]; P = .07) or chronic pseudocysts (7 of 59 [12%]; P = .047) (Table 50.1).

In more recent reports, necrosis is treated more aggressively by means of retroperitoneal endoscopic débridement after initial fistulization through, and balloon dilation of, the stomach wall104–108; whether this becomes the standard of care remains to be seen and is discussed in detail in another chapter. What is certain, however, is that pseudocyst and necrosis drainage are not risk-free, and these therapies must be used alongside other treatment modalities including open and laparoscopic surgery and percutaneous drainage. Because it is unlikely that a randomized prospective trial would be done comparing these individual modalities or that the results could be generalized to institutions with different levels of subspecialty strengths and skills, it is imperative for physicians who care for such patients to work with a team that includes endoscopists, surgeons, and interventional radiologists.

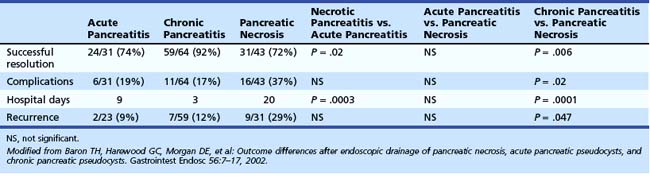

Numerous series have looked at either EUS or standard luminal endoscopy or surgery for pseudocyst drainage.66,73,93,109 Varadarajulu and associates110 randomly assigned patients to various endoscopic techniques of pseudocyst drainage and concluded that EUS procedures were more successful. The same group showed that EUS-facilitated procedures had efficacy and complications comparable to surgery, although patients with endoscopic treatment had statistically significant decreased costs and resource use compared with patients treated surgically.84 Our group previously reported 133 patients with severe necrosis (Balthazar score ≥ 6) treated with multimodality therapy (Fig. 50.3).9 We showed that 76% of these patients had ductal disruption including side branch or major ductal leak and disconnected gland syndrome. Of the 115 patients to undergo ERCP, 70 (61%) had stent placement, 15 (13%) had cyst-gastrostomy or cyst-duodenotomy, 11 (9.6%) had a nasopancreatic drain, and 11 (9.6%) had a nasobiliary drain. In addition, 98 of 133 (74%) had placement of one or more large Jackson-Pratt drains, and 75 patients ultimately required elective surgery including pancreatic resection in 47 (33%) for glandular disconnection. Mean hospital days approximated 1 month, and there was a 9% mortality rate in this exceptionally sick group of patients, many with multisystem organ failure. These results equal or exceed previously reported outcomes in surgical series using routine or selective débridement.4,111–115

Pancreatic Ascites and Pleural Effusions

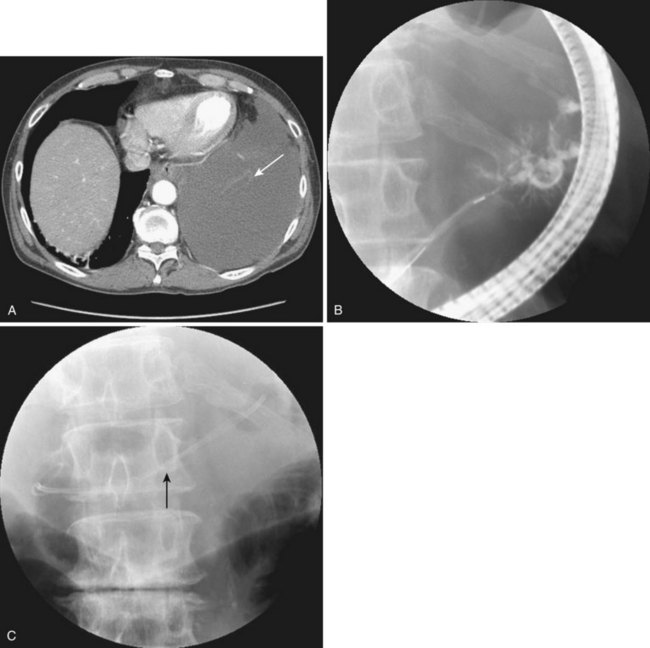

Historically, pancreatic ascites was treated by resting the pancreas to minimize flow and leak. Patients were given nothing by mouth, were given parenteral nutrition, and were started on somatostatin analogues.65,116–120 Diuretics and large-volume thoracentesis and paracentesis were commonly used before “salvage” operations—usually pancreatic resection or Roux-en-Y cyst-jejunostomy if a concomitant pseudocyst was present. Medical therapy was effective at best in half of the patients, and the subsequent surgical approach, usually predicated on anatomy as defined by preoperative ERCP, was associated with an 8% to 15% periprocedural mortality and a 15% recurrence rate.116–121 More than a decade ago, we showed that stent placement beyond a ductal disruption, with or without concomitant pseudocyst decompression, was effective therapy in a small group of patients with pancreatic ascites, particularly when combined with large-volume paracentesis (Figs. 50.4, 50.5, and 50.6).51,121 Bracher and coworkers122 confirmed our original findings, and 91% of patients had resolution of ascites without major complications. There were no recurrences in the two series at 60 months and 14 months. This approach apparently works by relieving upstream duct hypertension by bypassing the sphincter or an obstructing stone or inflammatory stenosis. It does not work with a disconnected gland syndrome in which most of the pancreatic juice enters the peritoneal or thoracic cavity from a disconnected tail; this condition is ultimately treated better with surgery.

Pancreaticoenteric Fistula and Acute Pancreatic Trauma

Our group previously reported successful healing of eight patients with pancreaticoduodenal (five patients) or pancreaticocutaneous (three patients) fistulas.59 Three patients healed after downsizing or removal of an external drain, three patients had healing of their fistulas with transpapillary stent placement, and two patients ultimately required pancreatic resection. An additional six patients with pancreaticobiliary fistulas all were successfully treated using a combination of biliary sphincterotomy and pancreaticobiliary stent placement.9 ERCP has also been used to treat internal fistulas associated with acute pancreatic trauma.6 Kim and colleagues21 noted injury to the pancreatic duct in 14 of 23 patients, including 8 patients who had leakage into the pancreatic parenchyma that resolved spontaneously. An additional three patients had a leak from the main pancreatic duct and responded to transpapillary stent placement. These authors believed that early ERCP with directed therapy (i.e., medical, endoscopic, surgical) was advantageous in the setting of acute pancreatic trauma and potential ductal leak.

External Fistulas

As previously noted, external pancreatic fistulas are usually iatrogenic. Etiologies include surgical or percutaneous drainage of a pancreatic fluid collection with an ongoing ductal disruption as a consequence of a disconnected gland or downstream obstruction from a stone or stricture. Fistulas may also follow partial pancreatic resection or bypass or result from penetrating abdominal trauma.1,3,7,65,123 Since our initial report using variable length prostheses bridging ductal disruptions for head or body leaks and placing short transpapillary stents alone in postoperative tail disruptions without downstream obstruction,124 multiple additional series have been published.125–127 Of 58 patients with an average fistulous output of 200 mL/day, 50 (86%) had successful stent placement, 46 of whom (92%) had resolution of the fistula within 5 weeks. Several patients experienced minor flares of pancreatitis, and two deaths occurred in one of the series, unrelated to the fistula or endotherapy. Contingent on the series, there were no recurrences in follow-up ranging from 12 to 36 months. More recently, Pelaez-Luna and colleagues2 at the Mayo Clinic looked at their experience with the disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome in several subsets of patients with acute pancreatitis, including patients with external fistulas. Endoscopy improved manifestations of leakage in 19 of 26 patients in whom it was attempted. For patients who successfully avoided surgery, pancreatic atrophy of the disconnected portion was common and associated with development of diabetes in 10%.

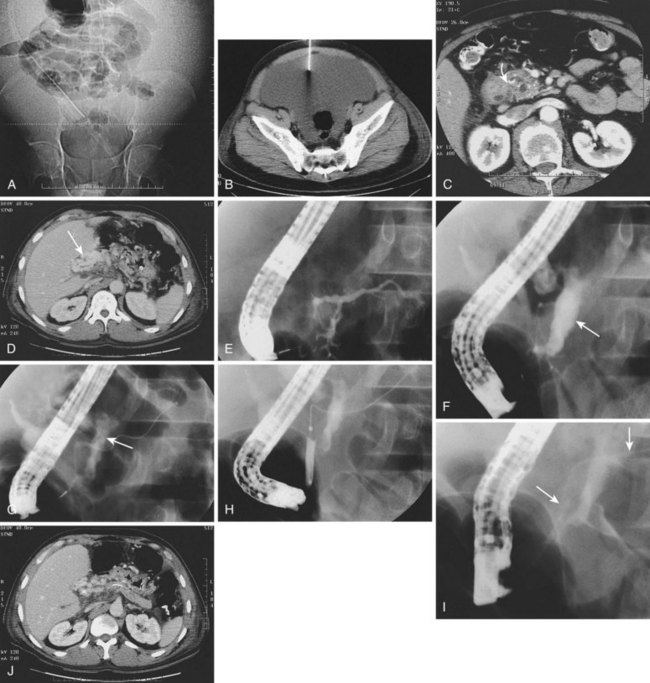

It is our practice to treat patients with enteral nutrition using formula diets or total parenteral nutrition when the patient is acutely ill with pancreatic necrosis, usually adding a somatostatin analogue if there is persistent high-amylase, high-volume Jackson-Pratt drain output.128–132 We may also treat postoperative patients with a persistent external fistula this way. However, if there is not dramatic and immediate decrease in fistulous output, our group is now studying these patients earlier in the course (<1 week) and attempting to place a transpapillary prosthesis if the anatomy is amendable (Fig. 50.7). Alternatively, in patients who remain unwell after 2 to 3 weeks, our group places transgastric stents into the necrotic cavity in conjunction with concomitant large-bore percutaneous drain placement in an attempt to preclude need for tail resection.132 In addition, there are individual reports and case series approaching a subset of such patients, particularly patients with disconnected glands, with various interventional radiologic techniques.123,132–134

Indications and Contraindications

The indications for treating a pancreatic duct leak are (1) persistence of an external fistula, (2) inability to refeed a patient without developing recurrent pain or pancreatitis, (3) enlarging pancreatic fluid collection (pseudocyst, pancreatic ascites, high-amylase, pleural effusion), or (4) symptomatic fluid collection. A fifth indication may be uncertainty about diagnosis, which is usually an issue only when attempting to differentiate pseudocysts from cystic neoplasms of the pancreas.1 Many more recent publications tend to lump the many manifestations of pancreatic duct leak together recognizing that evolving fluid collections in acute pancreatitis may have considerable necrotic debris and be better defined as walled-off pancreatic necrosis.5,135,136 Pseudocysts can leak, obstruct, or erode, causing manifestations such as concomitant pancreatic ascites, gastric outlet obstruction, or pseudoaneurysm or pancreaticoenteric fistula. Hookey and colleagues135 from Brussels lumped 116 patients, reporting an 87.9% successful treatment rate endoscopically and finding no difference in patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis. There was a significantly higher failure rate in patients with pancreatic necrosis. For all patients, there was an 11% complication rate, and 6 patients died within 30 days, with one death directly related to the drainage.

A comprehensive look at EUS-directed drainage of various pancreatic fluid collections was published in a 2008 EUS Working Group document (Table 50.2).48 From my perspective, the major contraindication to studying a patient is inability to apply therapy. It is potentially dangerous to perform ERCP in the setting of pancreatic necrosis or pseudocyst because of the potential of iatrogenic infection unless one is prepared to treat this leak. As noted previously, treatment can be directed at either the leak (transpapillary stent) or the consequences of the leak (see Box 50.4). Other contraindications are relative and include inability to give informed consent, anaphylaxis with iodinated contrast agents, and a patient so unstable that endoscopic diagnosis or therapy entails prohibitive procedural risk. In this setting, S-MRCP may define anatomy and leak site so that percutaneous drainage may initially be preferable to stabilize the patient.

Description of Technique

Placement of a pancreatic duct stent to bridge a ductal disruption is comparable to biliary stent placement for a cystic duct leak but with subtle differences. It should be undertaken only over a hydrophilic wire passed beyond the leak proper.3,7,136 Broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage should be routine. Biliary sphincterotomy would help access by exposing the pancreaticobiliary septum and the pancreatic orifice at the 5 o’clock position at the lower edge of the incision.8,137 I use pure cutting current if a pancreatic duct sphincterotomy is needed to improve access to the duct. Stent size is important, and one usually chooses 3-Fr, 5-Fr, 6-Fr, or 7-Fr pancreatic duct stents depending on the diameter of the duct and lengths that are 2 to 3 cm longer than the leak to be bridged (see Video![]() ). Depending on the situation, balloon or catheter dilation of concomitant strictures or stone removal may be necessary. Alternatively, in patients with ductal leaks in the tail, a short transpapillary stent usually is effective. Stents usually play no or a limited role in patients with central pancreatic necrosis and a disconnected gland syndrome. In the latter situation, most of the ongoing leak is from the tail, and small-caliber drains or stents are ineffective in removing the large chunks of necrotic debris often present.

). Depending on the situation, balloon or catheter dilation of concomitant strictures or stone removal may be necessary. Alternatively, in patients with ductal leaks in the tail, a short transpapillary stent usually is effective. Stents usually play no or a limited role in patients with central pancreatic necrosis and a disconnected gland syndrome. In the latter situation, most of the ongoing leak is from the tail, and small-caliber drains or stents are ineffective in removing the large chunks of necrotic debris often present.

Transgastric stents can be used as a placeholder to preclude formation of a chronic external fistula in patients who have undergone percutaneous catheter drainage in the setting of a disconnected duct syndrome.65,138 When stent placement is done for pancreatic ascites or pleural effusions, a large-volume paracentesis or thoracentesis under ultrasound guidance speeds the healing process considerably. As previously noted, endoscopic drainage of pseudocysts can be done in a transpapillary fashion, as described previously.7,8 Very large or complex pseudocysts are best drained by fistulizing into the collection using a duodenoscope with therapeutic capabilities.4,66,73,80,90 Pseudocysts can be localized by defining an extrinsic bulge on the stomach or duodenum or by more precise localization with EUS.2,48,83,91,92,94,95,99–101,109,138–141 EUS also has the advantage of Doppler capabilities to define vasculature, particularly in the setting of splenic vein thrombosis and gastric varices. I use a needle-knife sphincterotome with a 0.035-inch wire after initial localization by transgut injection of contrast material using a long sclerotherapy needle. Alternatively, localization and access can be accomplished using the Seldinger technique with a needle alone.50 When access has been gained into the cavity, I add a second guidewire, curling both deep within the pseudocyst proper (see Video![]() ). A 6- to 10-mm biliary dilating balloon is used to enlarge the tract followed by placement of at least two 7-Fr to 10-Fr double-pigtail stents of variable length. The latter not only prevent migration into or out of the pseudocyst but also allow drainage between the stents if stent occlusion should occur. I routinely aspirate fluid from the cyst for Gram stain, culture and sensitivity, amylase level, and cytology at the time of drainage, and I routinely perform ERCP and place an additional transpapillary stent if an amendable ongoing ductal leak is shown.

). A 6- to 10-mm biliary dilating balloon is used to enlarge the tract followed by placement of at least two 7-Fr to 10-Fr double-pigtail stents of variable length. The latter not only prevent migration into or out of the pseudocyst but also allow drainage between the stents if stent occlusion should occur. I routinely aspirate fluid from the cyst for Gram stain, culture and sensitivity, amylase level, and cytology at the time of drainage, and I routinely perform ERCP and place an additional transpapillary stent if an amendable ongoing ductal leak is shown.

Variations and Unusual Situations

The most common scenario that one encounters when draining pseudocysts is considerable necrotic debris interspersed with a liquid interface (walled-off pancreatic necrosis or abscess); this occurs because abdominal CT scan routinely underestimates debris in pancreatic fluid collections.15 When this scenario occurs, options are to use even larger balloons and perform a retroperitoneal necrosectomy with a therapeutic endoscope,97,100,106–108 add multiple large-diameter percutaneous catheters,36 or leave one or more nasocystic drains in place and perform large-volume and repeated irrigations (see Video![]() ).10 Surgery (débridement) may also be necessary, particularly if one inadvertently infects a necrotic cavity and the cavity is inaccessible for percutaneous drainage.9

).10 Surgery (débridement) may also be necessary, particularly if one inadvertently infects a necrotic cavity and the cavity is inaccessible for percutaneous drainage.9

Postoperative Care and Complications

The most common acute complications when using endoscopy to treat pancreatic fistulas are exacerbation of pancreatitis and iatrogenic infection,7,8,50,135,141 although the full range of potential procedural problems (e.g., aspiration, drug reaction, bleeding, perforation) must be discussed with the patient and family. Postoperative care must be anticipatory with routine measurement of pulse, temperature, and constitutional complaints and blood studies including a complete blood count, amylase, lipase, and a liver profile. Pancreatitis flare is more common with otherwise normal pancreatic ducts and is contingent on the amount of manipulation and the success of the procedure. It approximates 10% in my practice, is close to 0 in patients with extensive chronic pancreatitis, and is usually of the mild variety. Iatrogenic infection often follows placement of small catheters or stents in large, debris-filled cavities, and proactive treatment with larger percutaneous Jackson-Pratt drains and a 7- to 10-day course of oral antibiotics is usually indicated. I have also learned to minimize use of antisecretory drugs (i.e., proton pump inhibitors, histamine-2 blockers) because these are associated with significantly higher intraluminal gastric bacteria counts and seem to increase the risk of bacterial translocation and cavity infection. Finally, pancreatic duct stent placement by itself is associated with the colonization of bacteria within the duct proper. We have noted that pancreatic sepsis, previously thought to be uncommon because of the inhibitory effect of pancreatic enzymes, is noted in a small subset of patients even without a ductal disruption and seems to be more common in patients who have occlusion of prostheses.142

Longer term complications of transpapillary stent placement include iatrogenic ductitis, such as focal strictures and side branch ectasis.143 It is prudent to remove prostheses as soon as feasible after placement; this is easy to define in patients with an external fistula. In this setting, stents can be removed 5 to 7 days after fistula closure, removal of the external Jackson-Pratt drain, and abdominal CT scan to ensure that there has been no recurrence of an undrained fluid collection. I usually leave stents in place for internal fistulas for 4 to 6 weeks, but 8.5-Fr to 10-Fr stents can be left in place for 3 to 4 months in patients with chronic pancreatic leaks and downstream stones or strictures. Transgastric or transenteric stents are usually left in place for 4 to 6 weeks after ensuring resolution of the pseudocyst at follow-up CT examination. An exception may be a high-risk surgical patient with a disconnected pancreas in whom stent retrieval is usually associated with recurrent pseudocyst.103 In this setting, and only this setting, a long-term indwelling pancreatic stent is occasionally justified.

Future Trends

Although one can speculate that prostheses will be developed that have prolonged patency and cause minimal ductitis obviating the urgency of removal, there are numerous trends in diagnosis and treatment that are likely to continue in the future. One trend is the use of S-MRCP to define the presence or absence of a pancreatic fistula and its location. Another trend is likely earlier use of ERCP in patients with pancreatic necrosis with placement of transpapillary prostheses to limit further necrosis and to prevent additional local complications and the use of concomitant pancreatic stents in necrotic cavities being treated percutaneously to prevent external fistulas in patients with the disconnected duct syndrome. Although our group has currently adopted this practice model, prospective multicenter trials are needed before I would recommend widespread acceptance of this approach. Superglue (cyanoacrylate) or fibrin injection to occlude a disconnected duct either percutaneously or by EUS may also gain more acceptance in the treatment of disconnected pancreatic duct tail as a means to avoid distal pancreatectomy. In addition, the endoscopic approach to the débridement of pancreatic necrosis may be standardized. This standardization would require new endoscopic accessories, a change in mindset such that multiple endoscopic procedures are the expectation as opposed to the exception, and an even closer working relationship with surgical colleagues. There have been case reports more recently using a per os stapler to effect a pseudocyst gastrostomy,107 a device classically limited to open or laparoscopic surgery.

Finally, one hopes that many patients with ductal disruption will be sent to centers with expertise in their treatment. Similar to all techniques and procedures, data clearly show that endoscopists who have drained more than 20 pseudocysts have significantly better results draining pancreatic fluid collections than endoscopists who have drained fewer than 20.30,144 In other words, endoscopists who dabble in drainage probably should not.

1 Lau ST, Simchuk EJ, Kozarek RA, et al. A pancreatic ductal leak should be sought to direct treatment in patients with acute pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2001;181:411-415.

2 Pelaez-Luna M, Vege SS, Petersen BT, et al. Disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome in severe acute pancreatitis: Clinical and imaging characteristics and outcomes in a cohort of 31 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:91-98.

3 Kozarek RA. Pancreatic endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2008;40:55-60.

4 Baron TH. Treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts, pancreatic necrosis, and pancreatic duct leaks. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17:559-579.

5 Reid-Lombardo KM, Farrell MB, Crippa S, et al. Pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreatico-duodenectomy in 1507 patients: A report from the Pancreatic Anastomotic Leak Study Group. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1451-1459.

6 Kantharia CV, Prabhu RY, Dalvi AN, et al. Spectrum and outcome of pancreatic trauma. Trop Gastroenterol. 2007;28:105-108.

7 Kozarek RA, Traverso LW. Pancreatic fistulas and ascites. In: Brandt JL, editor. Textbook of clinical gastroenterology. Philadelphia: Current Medicine; 1998:1175-1181.

8 Kozarek RA. Endoscopic therapy of complete and partial pancreatic duct disruptions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1998;8:39-53.

9 Kozarek RA, Attia FM, Traverso LW, et al. Pancreatic duct leak in necrotizing pancreatitis: Role of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP as part of a multi-disciplinary approach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:AB138.

10 Baron TH, Morgan DE. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1412-1417.

11 Baron TH, Thaggard WB, Morgan DE, et al. Endoscopic therapy for organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:755-764.

12 Uomo G, Molino D, Visconti M, et al. The incidence of main pancreatic duct disruption in severe biliary pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1998;176:49-52.

13 Balthazar EJ, Robinson DL, Megibow AJ, et al. Acute pancreatitis: Value of CT in establishing prognosis. Radiology. 1990;174:331-336.

14 Sauvanet A, Partensky C, Sastre B, et al. Medial pancreatectomy: A multi-institutional retrospective study of 53 patients by the French Pancreas Club. Surgery. 2002;132:836-843.

15 Memis A, Parildar M. Interventional radiological treatment in complications of pancreatitis. Eur J Radiol. 2002;43:219-228.

16 Halloran CM, Ghaneh P, Bosonnet L, et al. Complications of pancreatic cancer resection. Dig Surg. 2002;19:138-146.

17 Sheehan MK, Beck K, Creech S, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: Does the method of closure influence fistula formation? Am Surg. 2002;68:264-268.

18 Poon RT, Lo SH, Fong D, et al. Prevention of pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183:42-52.

19 Freeny PC, Hauptmann E, Althaus SJ, et al. Percutaneous CT-guided catheter drainage of infected acute necrotizing pancreatitis: Techniques and results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:969-975.

20 Nordback I, Paajanen H, Sand J. Prospective evaluation of a treatment protocol in patients with severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Eur J Surg. 1997;163:357-364.

21 Kim HS, Lee DK, Kim IW, et al. The role of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography in the treatment of traumatic pancreatic duct injury. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:49-55.

22 Sandrasegaran K, Tann M, Jennings G, et al. Disconnection of the pancreatic duct: An important but over-looked complication of severe acute pancreatitis. Radiographics. 2007;27:1389-1400.

23 Habashi S, Draganov PV. Pancreatic pseudocyst. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:38-48.

24 Evans KA, Clark CW, Vogel SB, et al. Surgical management of failed endoscopic treatment of pancreatic disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1924-1929.

25 Bradley EL3rd, Howard TJ, van Sonnenberg E, et al. Intervention in necrotizing pancreatitis: An evidence-based review of surgical and percutaneous alternative. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:634-639.

26 Frakes JT. Biliary pancreatitis: A review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:97-109.

27 Enns R, Baillie J. The treatment of acute biliary pancreatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1379-1389.

28 Forsmark CE. The clinical problem of biliary acute necrotizing pancreatitis: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of biliary necrotizing pancreatitis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:235-239.

29 Ashley SW, Perez A, Pierce EA, et al. Necrotizing pancreatitis: Contemporary analysis of 99 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2001;234:572-580.

30 Isenmann R, Rau B, Beger HG. Bacterial infection and extent of necrosis are determinants of organ failure in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1020-1024.

31 Büchler MW, Gloor B, Muller CA, et al. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis: Treatment strategy according to the status of infection. Ann Surg. 2000;232:619-626.

32 Pezzilli R, Uomo G, Zerbi A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis: The position statement of the Italian Association for the study of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:803-808.

33 Oksuz MO, Altehoefer C, Winterer JT, et al. Pancreatico-mediastinal fistula with a mediastinal mass lesion demonstrated by MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:746-750.

34 De Backer AI, Mortele KJ, Vaneerdeweg W, et al. Pancreatocolonic fistula due to severe acute pancreatitis: Imaging findings. JBR-BTR. 2001;84:45-47.

35 Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG, Farnell MB. Pancreaticobiliary fistula: An unusual complication of necrotizing pancreatitis. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:151-153.

36 Szentes MJ, Traverso LW, Kozarek RA. Invasive treatment of pancreatic fluid collections with surgical and nonsurgical methods. Am J Surg. 1991;161:600-605.

37 Heider R, Behrns KE. Pancreatic pseudocysts complicated by splenic parenchymal involvement: Results of operative and percutaneous management. Pancreas. 2001;23:20-25.

38 Salih A. Massive pleural effusion. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:536. 546–547

39 Kaman L, Behera A, Singh R, et al. Internal pancreatic fistulas with pancreatic ascites and pancreatic pleural effusions: Recognition and management. Aust N Z J Surg. 2001;71:221-225.

40 Ito H, Matsubara N, Sakai T, et al. Two cases of thoracopancreatic fistula in alcoholic pancreatitis: Clinical and CT findings. Radiat Med. 2002;20:207-211.

41 Suzuki A, Suzuki S, Sakaguchi T, et al. Colonic fistula associated with severe acute pancreatitis: Report of two cases. Surg Today. 2008;38:178-183.

42 Isenmann R, Rau B, Beger HG. Bacterial infection and extent of necrosis are determinants of organ failure in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1020-1024.

43 Kozarek RA. Therapeutic pancreatic endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2001;33:39-45.

44 Wyncoll DL. The management of severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis: An evidence-based review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:146-156.

45 Slavin J, Ghaneh P, Sutton R, et al. Management of necrotizing pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:476-481.

46 Gibbs CM, Baron TH. Outcomes following endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic fluid collections in outpatients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:634-637.

47 Roth JS, Park AE. Laparoscopic pancreatic cystgastrostomy: The lesser sac technique. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2001;11:201-203.

48 Seewald J, Ang TL, Kida M, et al. EUS 2008 working group document: Evaluation of EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections (with video). Gastroeintest Endosc. 2009;69:S13-S21.

49 Hocke M, Will U, Gottschalk P, et al. Transgastral retroperitoneal endoscopy in septic patients with pancreatic necrosis or infected pancreatic pseudocysts. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:1363-1368.

50 Baron TH, Harewood GC, Morgan DE, et al. Outcome differences after endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, and chronic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:7-17.

51 Kozarek RA, Jiranek GC, Traverso LW. Endoscopic treatment of pancreatic ascites. Am J Surg. 1994;168:223-226.

52 Büchler P, Reber HA. Surgical approach in patients with acute pancreatitis: Is infected or sterile necrosis an indication—in whom should this be done, when, and why? Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1999;28:661-671.

53 Manfredi R, Costamagna G, Brizi MG, et al. Severe chronic pancreatitis versus suspected pancreatic disease: Dynamic magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography after secretin stimulation. Radiology. 2000;214:849-855.

54 Urakami A, Tsunoda T, Hayashi J, et al. Spontaneous fistulization of a pancreatic pseudocyst into the colon and duodenum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:949-951.

55 Carrere C, Heyries L, Barthet M, et al. Biliopancreatic fistulas complicating pancreatic pseudocysts: A report of three cases demonstrated by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy. 2001;33:91-94.

56 Nealon WH, Walser E. Main pancreatic ductal anatomy can direct choice of modality for treating pancreatic pseudocysts (surgery versus percutaneous drainage). Ann Surg. 2002;235:751-758.

57 Kozarek RA. Role of ERCP in acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:S231-S236.

58 Bounds BC, Brugge WR. EUS diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2001;50:27-31.

59 Wolfsen HC, Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, et al. Pancreaticoenteric fistula: No longer a surgical disease? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:117-121.

60 Sugiyama M, Abe N, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Preoperative endoscopic pancreatic stenting for safe local pancreatic resection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:1625-1627.

61 Ohwada S, Tanahashi Y, Ogawa T, et al. In situ vs ex situ pancreatic duct stents of duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy with Billroth I-type reconstruction. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1289-1293.

62 Suzuki Y, Fujino Y, Tanioka Y, et al. Selection of pancreaticojejunostomy techniques according to pancreatic texture and duct size. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1044-1048.

63 Li-Ling J, Irving M. Somatostatin and octreotide in the prevention of postoperative pancreatic complications and the treatment of enterocutaneous pancreatic fistulas: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Surg. 2001;88:190-199.

64 Suc B, Msika S, Fingerhut A, et al. Temporary fibrin glue occlusion of the main pancreatic duct in the prevention of intra-abdominal complications after pancreatic resection: Prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2003;237:57-65.

65 Deviere J, Antaki F. Disconnected pancreatic tail syndrome: A plea for multidisciplinarity. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:680-682.

66 Melman L, Azar R, Beddow K, et al. Primary and overall success rates for clinical outcomes after laparoscopic, endoscopic, and open pancreatic cystgastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:267-271.

67 Palanivelu C, Senthilkumar K, Madhankumar MV, et al. Management of pancreatic pseudocyst in the era of laparoscopic surgery—experience from a tertiary centre. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2262-2267.

68 Aljarabah M, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches for drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: A systematic review of published series. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1936-1944.

69 Vitas GJ, Sarr MG. Selected management of pancreatic pseudocysts: Operative versus expectant management. Surgery. 1992;111:123-130.

70 Yemos K, Laopodis B, Yemos J, et al. Surgical management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Minerva Chir. 1999;54:395-402.

71 Ramachadran CS, Goel D, Arora V, et al. Gastroscopic-assisted laparoscopic cystgastrostomy in the management of pseudocysts of the pancreas. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12:433-436.

72 Siperstein A. Laparoendoscopic approach to pancreatic pseudocysts. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2001;8:218-222.

73 Johnson MD, Walsh M, Henderson JM, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical management of pancreatic pseudocysts. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:586-590.

74 Pitchamoni CA, Agarwal N. Pancreatic pseudocysts: When and how should drainage be performed? Gastroenterol Clin. 1999;28:615-639.

75 van Sonnenberg E, Wittich GR, Chen KS, et al. Percutaneous drainage of infected and non-infected pancreatic pseudocysts: Experience in 101 cases. Radiology. 1989;170:759-761.

76 Rogers BH, Cicurel NJ, Seed RW. Transgastric needle aspiration of pancreatic pseudocyst through an endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1975;21:133-134.

77 Kozarek RA, Brayko CM, Harlan J, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:322-327.

78 Vidyarthi G, Steinberg SE. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:405-410.

79 Sharma SS, Bhargawa N, Govil A. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocyst: A long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2002;34:203-207.

80 DePalma GD, Gallaro G, Puzzielo A, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: A long-term follow-up study of 49 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:1113-1115.

81 Mergener K, Kozarek RA. Therapeutic pancreatic endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:48-54.

82 Howell DA, Elton E, Parsons WG. Endoscopic management of pseudocysts of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1998;8:143-162.

83 Fuchs M, Reimann FM, Gaebel C, et al. Treatment of infected pancreatic pseudocysts by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided cystogastrostomy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:654-657.

84 Varadarajulu S, Lopez TL, Wilcox CM, et al. EUS versus surgical cyst-gastrostomy for management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:649-655.

85 Trevino JM. Initial experience with the prototype forward-viewing echoendoscope for therapeutic interventions other than pancreatic pseudocyst drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:361-365.

86 Sharma SS, Maharshi S. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocyst in children—a long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:1636-1639.

87 Ang TL, Teo EK, Fock KM. EUS-guided drainage of infected pancreatic pseudocyst: Use of a 101F Soehendra dilator to facilitate a double-wire technique for initial transgastric access (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:192-194.

88 Chen KH, Hsu HM, Hsu GC, et al. Therapeutic strategies for pancreatic pseudocysts: Experience in Taiwan. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1470-1474.

89 Barthet M, Lamblin G, Gasmi M, et al. Clinical usefulness of a treatment algorithm for pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:245-252.

90 Baron TH. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:369-372.

91 Lopes CV, Pesenti C, Bories E, et al. Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and abscesses. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:524-529.

92 Seewald S, Thonke F, Ang TL, et al. One-step, simultaneous double-wire technique facilitates pancreatic pseudocyst and abscess drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:805-808.

93 Kahaleh M, Shami VM, Conaway MR, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst: A prospective comparison with conventional endoscopic drainage. Endoscopy. 2006;38:355-359.

94 Kruger M, Schneider AS, Manns MP, et al. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts or abscesses after an EUS-guided 1-step procedure for initial access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:409-416.

95 Ahlawagt SK, Charabaty-Pishvaian A, Jackson PG, et al. Single-step EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage using a large channel linear array echoendoscope and cystotome: Results in 11 patients. JOP. 2006;7:616-624.

96 Pfaffenbach B, Langer B, Stabenow-Lohbauer E, et al. Endosonography controlled transgastric drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts [German with English abstract]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1998;123:1439-1442.

97 Giovannini M, Pesenti C, Rolland AL, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts or pancreatic abscesses using a therapeutic echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2001;33:473-477.

98 Reddy DN, Gupta R, Lakhtakia S, et al. Use of a novel balloon accessotome in transnasal drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:362-365.

99 Grimm H, Binmoeller KF, Soehendra N. Endosonography-guided pseudocyst drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:170-171.

100 Seifert H, Dietrich C, Schmitt T, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided one-step transmural drainage of cystic abdominal lesions with a large-channel echo-endoscope. Endoscopy. 2000;32:255-259.

101 Giovannini M, Pesenti C, Rolland AL, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts or pancreatic abscesses using a therapeutic echoendoscope. Endoscopy. 2001;33:473-477.

102 Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Patterson DJ, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary therapy for disrupted pancreatic duct and peripancreatic fluid collections. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1362-1370.

103 Deviere J, Bueso H, Baize M, et al. Complete disruption of the main pancreatic duct: Endoscopic management. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:445-451.

104 Seifert H, Wehrmann T, Schmitt T, et al. Retroperitoneal endoscopic debridement for infected peripancreatic necrosis. Lancet. 2000;356:653-655.

105 Seewald S, Groth S, Omar S, et al. Aggressive endoscopic therapy for pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic abscess: A new safe and effective treatment algorithm. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:92-100.

106 Charnley RM, Lochan R, Gray H, et al. Endoscopic necrosectomy as primary therapy in the management of infected pancreatic necrosis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:925-928.

107 Voermans RP, Veldkamp MC, Rauws EA, et al. Endoscopic transmural debridement of symptomatic organized pancreatic necrosis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:909-916.

108 Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, et al. Long-term outcome of endoscopic pancreatic necrosectomy: Final results of the first German multi-center trial [abstract]. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:AB360.

109 Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Tamhane A, et al. Role of EUS in drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections not amenable for endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1107-1119.

110 Varadarajulu S, Chistein JD, Tamhara A, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transnasal drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1102-1111.

111 Fernandez-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Makary MA, et al. Debridement and closed packing for the treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1998;228:676-684.

112 Takeda K, Matsuno S, Sunamura M, et al. Surgical aspects and management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: Recent results of a cooperative national survey in Japan. Pancreas. 1998;16:316-322.

113 Schoenberg MH, Rau B, Beger HG. New approaches in surgical management of severe acute pancreatitis. Digestion. 1999;60(Suppl S1):22-26.

114 Kasperk R, Riesener KP, Schumpelick V. Surgical therapy of severe acute pancreatitis: A flexible approach gives excellent results. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:467-471.

115 Rau B, Pralle U, Mayer JM, et al. Role of ultrasonographically guided fine-needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis of infected pancreatic necrosis. Br J Surg. 1998;85:179-184.

116 Torres AJ, Landa JI, Moreno-Azcoita M, et al. Somatostatin in the management of gastrointestinal fistulas: A multicenter trial. Arch Surg. 1992;127:97-100.

117 Parekh D, Segal I. Pancreatic ascites and effusion: Risk factors for failure of conservative therapy and the role of octreotide. Arch Surg. 1992;127:707-712.

118 Uchiyama T, Yamamoto T, Mizuta E. Pancreatic ascites—a collected review of 37 cases in Japan. Hepatogastroenterology. 1989;36:244-248.

119 Pederzoli P, Bassi C, Falconi M, et al. Conservative treatment of external pancreatic fistulas with parenteral nutrition alone or in combination with continuous intravenous infusion of somatostatin, glucagon or calcitonin. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1986;163:428-432.

120 Martin FM, Rossi RL, Munson JL, et al. Management of pancreatic fistulas. Arch Surg. 1989;124:571-573.

121 Kozarek RA, Patterson DJ, Ball TJ, et al. Endoscopic placement of pancreatic stents and drains in the management of pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1989;209:261-266.

122 Bracher GA, Manocha AP, DeBanto JR, et al. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stenting to treat pancreatic ascites. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:710-715.

123 Bosscha K, Hulstaert PF, Hennipman A, et al. Fulminant acute pancreatitis and infected necrosis: Results of open management of the abdomen and “planned” reoperation. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:255-262.

124 Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Patterson DJ, et al. Transpapillary stenting for pancreaticocutaneous fistulas. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997;1:357-361.

125 Costamagna G, Mutignani M, Ingrosso M, et al. Endoscopic treatment of postsurgical external pancreatic fistulas. Endoscopy. 2001;33:317-322.

126 Saeed ZA, Ramirez FC, Hepps KS. Endoscopic stent placement for internal and external pancreatic fistulas. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1213-1217.

127 Ukita T, Moriyama A, Tada A, et al. Successful management of postoperative pancreatic fistula by application of constructed S-type pancreatic stent after operation for abnormal biliary-pancreatic junction. Endoscopy. 2003;35:253.

128 Tulassay Z, Flautner L, Vadasz A, et al. Short report: Octreotide in the treatment of external pancreatic fistulas. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993;7:323-325.

129 Lansden FT, Adams DB, Anderson MC. Treatment of external pancreatic fistulas with somatostatin. Am Surg. 1989;55:695-698.

130 Prinz R, Pickleman J, Hoffman JP. Treatment of pancreatic cutaneous fistulas with a somatostatin analog. Am J Surg. 1988;155:36-42.

131 Ross A, Gluck M, Irani S, Fotoohi M, et al. Combined endoscopic and percutaneous drainage of organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:79-84.

132 Cope C, Tuite C, Burke DR, et al. Percutaneous management of chronic pancreatic duct strictures and external fistulas with long-term results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:104-110.

133 Sheiman RG, Chan R, Matthews JB. Percutaneous treatment of a pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:524-526.

134 Hirota M, Kamekawa K, Tashima T, et al. Percutaneous embolization of the distal pancreatic duct to treat intractable pancreatic juice fistula. Pancreas. 2001;22:214-216.

135 Hookey LC, Debroux S, Delhaye M, et al. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic fluid collections in 116 patients: A comparison of etiologies, drainage techniques, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:635-643.

136 Varadarajulu S, Tamhane A, Blakely J. Graded dilation technique for EUS-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections: An assessment of outcomes and complications and technical proficiency (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:656-666.

137 Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Patterson DJ, et al. Endoscopic pancreatic duct sphincterotomy: Indications, technique, and analysis of results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:592-598.

138 Antillon MR, Shah RJ, Stiegmann G, et al. Single-step EUS-guided transmural drainage of simple and complicated pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:797-803.

139 Sanchez Cortes E, Maalak A, Le Moine O, et al. Endoscopic cystenterostomy of nonbulging pancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:380-386.

140 Seifert H, Faust D, Schmitt T, et al. Transmural drainage of cystic peripancreatic lesions with a new large-channel echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2001;33:1022-1026.

141 Azar RR, Oh YS, Janee EM, et al. Wire-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage by using a modified needle knife and therapeutic echoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:688-692.

142 Kozarek RA, Hovde O, Attia F, et al. Do pancreatic duct stents cause or prevent pancreatic sepsis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:508-509.

143 Smith MT, Sherman S, Ikenberry SO, et al. Alterations in pancreatic ductal morphology following polyethylene pancreatic stent therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:268-275.

144 Harewood GC, Wright CA, Baren TH. Impact on patient outcomes of experience in the performance of endoscopic pancreatic fluid collection drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:230-235.