19 Palpable asymptomatic abdominal masses

Case

Mrs PA, a 45-year-old previously well woman presented to her general practitioner for a health check as part of a life insurance renewal. She denied any current illness or symptom, but when her general practitioner carried out an abdominal examination a mass was palpated in the right upper quadrant. The mass was smooth, slightly tender and moved with respiration, suggesting it arose in the liver. Following first principles, her doctor first of all revisited her medical history and noted that Mrs X had been on the oral contraceptive pill for more than 20 years. Furthermore, on close questioning she admitted to intermittent low grade abdominal discomfort in the right upper quadrant over several years, but a little more frequently over the last few months. However, her general practitioner could not identify any other hepatic disease risk factor in her history, such as intravenous drug use or other exposure to hepatitis B or C infection, or exposure to hydatid disease, and could find no other physical abnormality, in particular no evidence of chronic liver disease. Mrs X was referred for liver function tests, viral screens and an abdominal ultrasound scan. Her transaminase levels were mildly elevated, hepatitis B and C serology were negative and there was a solid mass seen on ultrasound scanning. Mrs X was referred to a multidisciplinary hepatology unit and, after more detailed investigation, was eventually found to have a 12-cm mass protruding from the inferior margin of hepatic segment 5. The imaging characteristics including the presence of a central scar were consistent with focal nodular hyperplasia, thought to be unrelated to her oral contraceptive pill consumption. After discussion with a hepatologist, with a hepatic surgeon and with her general practitioner and family, Mrs X elected to undergo surgery for removal of the mass. Subsequent histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of focal nodular hyperplasia. Her recovery was uneventful.

Introduction

Other chapters in this book are orientated to evaluation of symptomatic abdominal masses, abdominal distension and lumps in the groin. Chapter 26 discusses masses detected as incidental findings on abdominal imaging (incidentalomas).

Documenting the Finding of an Abdominal Mass

How was the mass detected, who detected it and when?

Masses within the Abdominal Wall

The different types of abdominal wall hernias and their features are listed in Box 19.1. Abdominal wall hernias are generally easy to characterise as a cough impulse is usually present, the hernia may present in a characteristic position and it may be possible to reduce the hernia. To separate other masses found within the abdominal wall from masses within the abdominal cavity, ask the patient to contract the anterior abdominal muscles by lifting his or her head from the examining couch with hands behind head, or to straight leg raise both legs simultaneously while keeping the head on the bed. This may help to define the mass as follows:

Box 19.1 Causes of abdominal wall masses

Lumps specific to the anterior abdominal wall

Herniae

Retroperitoneal Masses

The retroperitoneal region is subdivided into five regions:

Intraabdominal Masses

Site

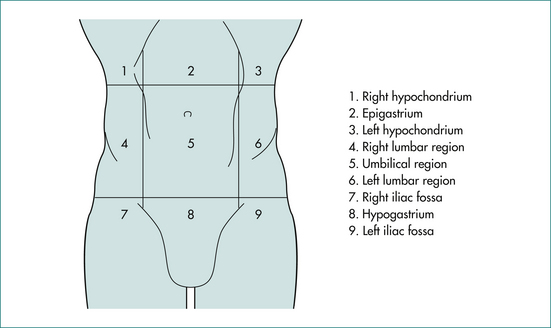

On the basis of position (Fig 19.1), we can start to define the likely organ of origin of an intraabdominal mass as shown in Table 19.1. However, we cannot be certain of the organ of origin of a palpable mass on the basis of its position alone. Organs do not necessarily enlarge concentrically from a fixed point. The pattern of enlargement may be determined by surrounding structures, by retroperitoneal attachments and by the pathological process responsible for the organ enlargement. The liver, for example, is limited by the diaphragm along the superior surface and by the diaphragm and ribs along the lateral surface and so tends to enlarge downwards and inwards. The uterus and bladder are limited by the pelvic walls laterally and below and so tend to enlarge upwards in the midline. The kidneys, aorta and pancreas are retroperitoneal and limited behind by the posterior abdominal wall and so tend to expand from their original site in all directions except posterior. An enlarged segment of small bowel is usually not found in the upper reaches of the abdomen because the transverse mesocolon, the transverse colon and the greater omentum are attached to retroperitoneal tissues along a horizontal line at the level of the inferior border of the pancreas. These three organs tend to form a barrier restricting upward migration of small bowel masses.

Table 19.1 Organ of origin of intraabdominal masses by region

| Right hypochondrium | Epigastrium | Left hypochondrium |

|---|---|---|

| Right lobe of liver | Stomach | Spleen |

| Gall bladder | Left lobe of liver | Pancreas∗ |

| Pancreas∗ | Stomach | |

| Lymph nodes∗ | ||

| Aorta∗ | ||

| Right lumbar region | Periumbilical | Left lumbar |

| Ascending colon∗ | Omentum | Descending colon∗ |

| Right kidney∗ | Transverse colon | Left kidney∗ |

| Aorta∗ | ||

| Retroperitoneal nodes∗ | ||

| Right iliac fossa | Hypogastrium | Left iliac fossa |

| Appendix | Bladder | Sigmoid colon |

| Caecum∗ | Uterus | Iliac aneurysm∗ |

| Iliac aneurysm∗ | Right and left ovary∗ | Left ovary∗ |

| Right ovary | Iliac nodes∗ | |

| Iliac nodes∗ |

∗ Strictly retroperitoneal in position

The likely organ of origin may be defined by the position of the mass as in Table 19.1.

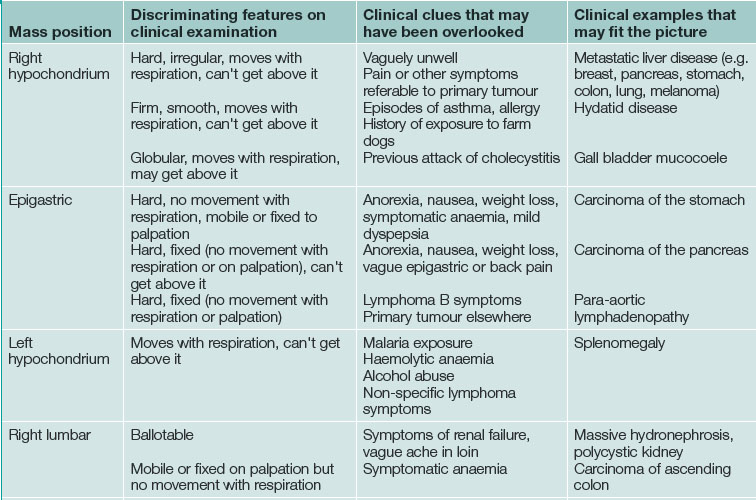

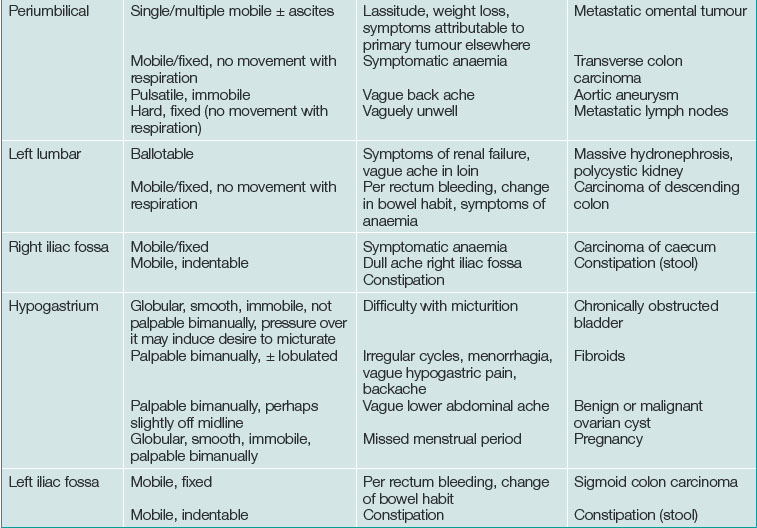

Discriminating clues that may be found on examination and that the patient may report on closer questioning may help establish the causative process. See Table 19.2 and Box 19.2.

Movement with respiration

The diaphragm moves inferiorly with inspiration and back up to its neutral position with expiration. Immediately below the diaphragm are the liver and the spleen. An enlarged liver or spleen will move inferiorly with each inspiratory effort. As well as moving inferiorly, the liver edge and the inferior pole of the spleen move medially relative to the costal margin.

Shape, edge and consistency

The most common asymptomatic intraabdominal mass is caused by faecal loading of a segment of colon (Fig 19.3), usually caecum or sigmoid colon. A loaded colon tends to be tubular or sausage-shaped with a lobular surface contour. The orientation of a caecum loaded with faeces is vertical, while that of sigmoid colon is oblique, parallel to the inguinal ligament. Pressure on the surface of the mass by pressing a finger or thumb into it through the anterior abdominal wall may result in indentation of the surface of the mass. This is an uncommon but characteristic diagnostic feature of constipation with faecal loading.

Single or multiple

If more than one mass is found, the differential diagnosis is narrowed. The most common cause of multiple abdominal masses is constipation. The next most common cause is multiple peritoneal secondaries.

Tender or non-tender

An asymptomatic abdominal mass is unlikely to be tender. Tenderness implies inflammation, which may be due to infection, infarction or haemorrhage into the mass (Table 19.3).

| Position of mass | Features on examination | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Right hypochondrium | Localised, moves with respiration, can’t get above it |

Acute cholecystitis, empyema of the gall bladder Haemorrhage or infarction in a liver tumour (or cyst) |

| Right hypochondrium | Enlarged liver | Cholangitis Portal pyaemia Hepatic metastases Acute severe right heart failure |

| Epigastric | Immobile | Pancreatic pseudocyst Pancreatic phlegmon Dissection in abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Left hypochondrium | Enlarged spleen | Splenic infarct |

| Right loin | Enlarged kidney | Pyonephrosis Renal cell carcinoma |

| Periumbilical | Pulsatile | Dissection in abdominal aortic aneurysm |

| Right iliac fossa | Immobile | Appendix phlegmon/abscess Crohn’s disease |

| Hypogastrium | Enlarged bladder Enlarged uterus Enlarged ovary |

Acute urinary retention Haemorrhage or infarction in a fibroid Haemorrhage or infarction in an ovarian tumour/cyst Acute pyosalpinx |

| Left iliac fossa | Immobile, sometimes palpable bimanually | Acute diverticular phlegmon Diverticular abscess |

Bruit or silent

Auscultation over a mass may reveal a bruit. Bruits are most commonly limited to systole and are caused by turbulent (non-laminar) flow in a narrowed artery. A continuous or machinery bruit may be heard over an extremely vascular tumour. It signifies the presence of significant arteriovenous shunting within the tumour. A bruit over the liver may also occur in acute alcoholic hepatitis or with an arteriovenous malformation.

Bimanually palpable on rectal or vaginal examination

Several other important observations may be made during a rectal examination. First, the rectum may be loaded with faeces. This is consistent with the presence of one or more abdominal masses caused by constipation. Secondly, there may be evidence of peritoneal spread of a malignant tumour of the stomach, colon or ovary. The sign to seek is the presence of a hard, irregular and relatively fixed tumour mass anterior to the rectum at the tip of the examining finger on rectal examination (Blumer’s shelf), though this is rare. Finally, there may be blood on the glove from a previously unsuspected colon cancer or the hard irregular mass of a rectal tumour (Ch 22).

Having defined the features of the mass, the clinician should review the clinical history with a focus on symptoms possibly associated with the provisional diagnoses. On specific questioning, symptoms that were previously overlooked by the patient might be recalled (see Box 19.3).

Other signs on general physical examination

The physical examination is completed mindful of the working diagnosis, based on the finding of an abdominal mass. Specific examples of relevant positive findings are listed in Table 19.4.

Table 19.4 Examples of extraabdominal signs that may be associated with an asymptomatic abdominal mass

| Sign | Associated abdominal mass |

|---|---|

| Pallor | Gastrointestinal malignancy with occult bleeding |

| Wasting | Advanced malignancy |

| Signs of chronic liver disease (palmar erythema, spider naevi, gynaecomastia, testicular atrophy, ascites, caput medusae) | Splenomegaly associated with portal hypertension Hepatic mass due to hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis |

| Hard, fixed irregular breast lump Hard supraclavicular lymph node Signs of pleural effusion |

Hepatomegaly due to metastatic breast cancer Epigastric mass due to stomach cancer Mass of malignant origin or benign ovarian tumour (Meigs’ syndrome) |

Imaging

Plain radiology

Plain abdominal x-ray is useful in the detection of pathological calcification including:

A plain chest x-ray examination should also be performed and may reveal:

Ultrasound and CT

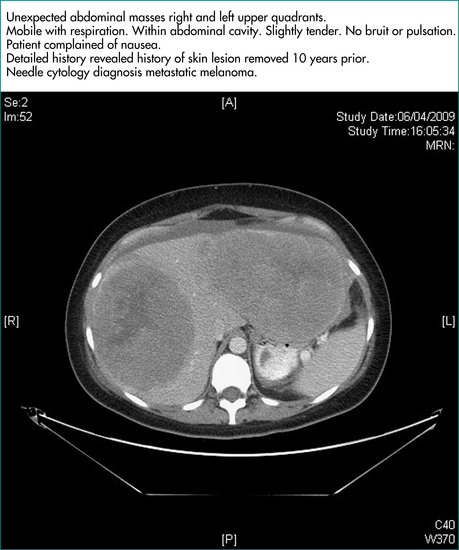

These modalities should allow definition of the abdominal organ involved and often, the pathologic process responsible for a palpable mass. Each scanning technique has particular advantages. Ultrasound scanning discriminates well between cystic and solid lesions. CT scanning is better in obese people as adjacent structures can be separated visually by intervening lucent fat planes. Ultrasound images are often suboptimal in obese patients. Further, if the space between the anterior abdominal wall and the palpable mass contains gas-filled loops of bowel, these will cast posterior shadows and distortions on the ultrasound scan images but not the CT scan images, making CT scanning the preferred technique for imaging of unexpected abdominal masses (Ch 26).

Confirmation of an abdominal mass or an enlarged abdominal organ on imaging

The next investigations depend on the results from ultrasound or CT scans.

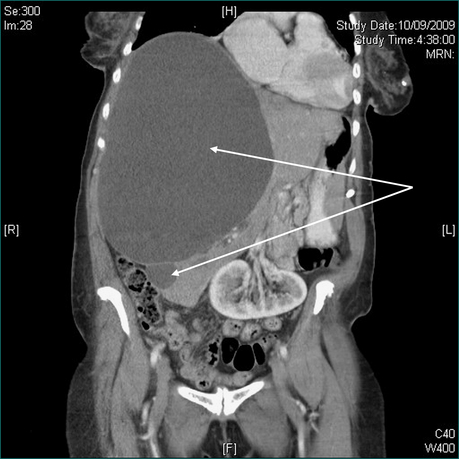

Liver

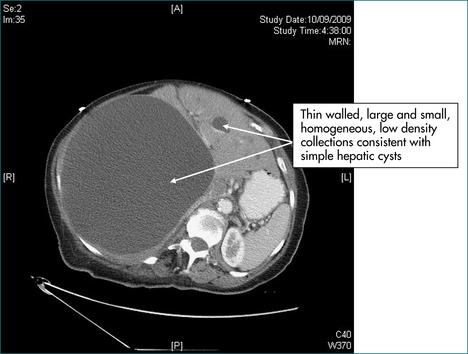

First, ask yourself: is the enlargement uniform or irregular? The possible causes of a diffuse, uniform enlargement are listed in Box 19.4. If CT has detected small, low density but non-specific lesions or if liver enlargement is irregular or patchy, ultrasound scanning is useful to determine whether the lumps are solid or cystic. Evaluation of lumps in the liver is discussed in detail in Chapter 26. Cystic hepatic lesions are most commonly due to simple cysts. These may be quite large, may be multiple and are frequently discovered incidentally (Fig 19.5A and 19.5B). Though rare, hepatic neoplastic cysts (cystadenomas) should be excluded. Hydatid cysts are not infrequent in Echinococcus spp. endemic areas but are generally easy to diagnose on ultrasound or CT scans, which usually reveal daughter cysts within the main cyst.

Box 19.4 Causes of hepatomegaly

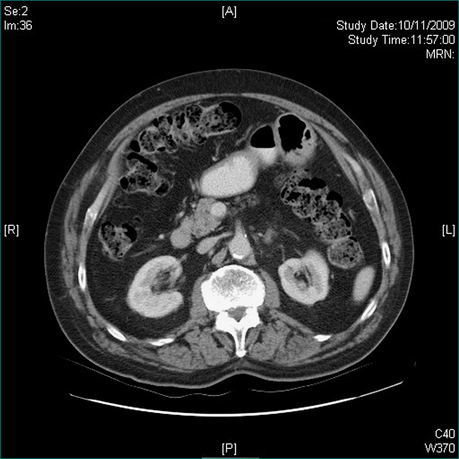

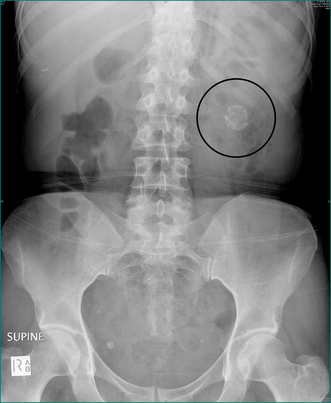

Figure 19.5 CT scans. Massive hepatic cyst detected on abdominal exam. Elderly patient admitted with a stroke.

If the hepatic lesion is single and solid, it is likely to be a solitary secondary deposit but may be a primary hepatoma, particularly if there is a history of chronic liver disease. The other single solid lesions discussed in Chapter 26 tend to be less massive and are less likely to cause hepatomegaly.

If hepatomegaly is due to multiple solid lesions, metastatic liver disease is the likely explanation. The next step will then be to establish the primary tumour site. The common sources are colon, pancreas, stomach, breast and lung. Histological confirmation of the diagnosis should usually be sought, provided this does not risk compromising the treatment and chances of cure by seeding along the biopsy track or by rupture of the tumour. A biopsy of the primary tumour is preferred as the histology from the liver may well be consistent with malignancy but still be non-discriminatory about the primary site. Furthermore, biopsy of a primary tumour, whether by gastroscopy, colonoscopy, bronchoscopy or needle biopsy, is generally safer than liver biopsy. If the primary tumour cannot be found, then ultrasound or CT-guided biopsy of the hepatic mass may be indicated to secure a diagnosis of metastatic disease but, even then, the primary site may remain enigmatic.

Gall bladder

Gall bladder enlargement due to obstruction of the common bile duct (e.g. carcinoma of the head of the pancreas or ampulla of Vater) will usually be associated with jaundice (Ch 23). A gallbladder mucocele usually forms a smooth, globular swelling in the right upper quadrant and may be relatively painless and non-tender. Enlargement due to carcinoma of the gall bladder is unusual.

Stomach

If the mass is thought to be gastric on CT, then gastric carcinoma or gastric lymphoma is the likely diagnosis. Gastroscopy and biopsy should confirm the diagnosis. Visualisation of the stomach by ultrasound scanning, and to a lesser extent by CT, is poor. Management of an asymptomatic tumour of the stomach will depend on the patient’s age and comorbidity as well as on the stage of the disease. Preoperative staging of gastric carcinoma includes a search for lymphatic, haematogenous and transcoelomic metastases and involves physical examination, CT scanning of the chest and abdomen and frequently, positron emission tomography (PET) scanning (Ch 17).

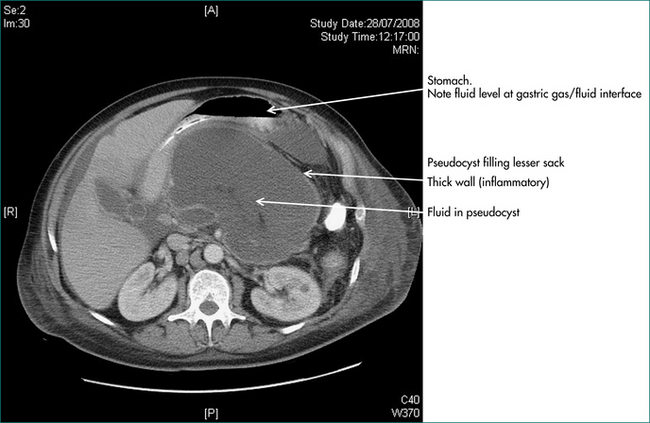

Pancreas

On the basis of the ultrasound or CT scans, the clinician should know whether a pancreatic lesion is cystic or solid. If cystic it is likely to be either a pseudocyst of the pancreas or a neoplastic cyst (cystadenoma or rarely cystadenocarcinoma) (see Fig 19.6). For the diagnosis of pseudocyst, there should have been a definite prior episode of pancreatitis. The management of pancreatic pseudocyst is discussed in Chapter 4. The treatment of cystadenoma is surgical resection (Ch 26).

If the lesion is solid, then pancreatic cancer is likely. On ultrasound scanning pancreatic cancers often have a characteristic hypo-echoic appearance. The CT scan should be examined for evidence of spread to the liver, to peripancreatic and portal lymph nodes, encasement of the portal vein or superior mesenteric vein and dilatation of the pancreatic duct. Most malignant pancreatic tumours that have grown to the point where they are palpable on physical examination will be unresectable. Many of these tumours will also have caused obstructive jaundice by obstructing the common bile duct in the pancreas (see Ch 23). Primary tumours of the body and tail of the pancreas may also cause jaundice indirectly, when metastatic portal lymph nodes obstruct the hepatic ducts at the porta hepatis. The management of pancreatic cancer is considered in Chapter 17.

Lymph nodes

Enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes producing an epigastric mass are likely to have arisen from a primary tumour elsewhere. The common sites of origin are the stomach, colon, pancreas and testis. The origin of the lymphadenopathy should be established by investigation of the likely primary site (see above). If no primary site is found, then an imaging guided percutaneous biopsy is reasonable. Cytology from a percutaneous needle aspiration biopsy may be non-diagnostic or inadequately specific for full tumour typing if the lymphadenopathy is due to malignant lymphoma (Ch 26). Core biopsy or an open biopsy may still be needed for histology.

Spleen

Truly incidental splenomegaly is a very uncommon finding. The spleen has to be enlarged to several times its normal size to be palpable so most patients with splenomegaly will have symptoms from the causative process before the spleen is palpable. The causes of splenomegaly include infections, inflammatory diseases and haematological diseases liver diseases (Box 19.5). The most important gastroenterological cause of splenomegaly is portal hypertension (see Ch 24).

Box 19.5 Causes of splenomegaly and hepatosplenomegaly

Small splenomegaly

Kidneys

The common causes of an enlarged kidney include obstructions, cysts, tumours and infections as shown in Box 19.6. If there is congenital or acquired absence of a kidney or if renal disease has resulted in unilateral renal atrophy, the remaining kidney will undergo compensatory hypertrophy and may become palpable. A careful clinical history and an ultrasound scan should clarify this situation.

Colon

Faecal masses (Fig 19.3) are quite firm but should be indentable and should disappear with purgation. Neoplastic masses arising in the colon are usually firm to hard. They may or may not be mobile, but do not indent. As is also the case for masses in the stomach, colonic masses are poorly imaged by ultrasound. By the time colonic neoplastic masses are palpable, the origin in colon can usually be determined by CT scan. However, conclusive diagnosis requires a tissue biopsy for histopathology. Biopsy usually requires a colonoscopy. Staging of malignant tumours is described in Chapter 22.

Small bowel

A palpable small bowel mass will be apparent on CT. The causes of asymptomatic small bowel masses are shown in Table 19.5. Unlike the stomach and the colon, endoscopy of the small bowel is difficult. If further radiological imaging of a small bowel mass is required after CT, it is usually achieved by small bowel series, often carried out as a small bowel enema or CT enterography. If radiological imaging has not been adequate and there is no suggestion of an obstructing lesion in the small bowel, capsule endoscopy may be indicated. Small bowel enteroscopy is available in highly specialised centres.

| Cause | Pathology | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Cyst | Mesenteric cyst |

Omentum

Normal omentum is never palpable. Omentum becomes palpable only when it is infiltrated by tumour, usually by transperitoneal spread (transcoelomic metastases). The common sites of origin of transcoelomic metastases are colon, ovary, stomach and pancreas. Melanoma is the most common extraabdominal primary malignancy causing metastases to the omentum and small bowel. Omental secondaries are usually associated with some degree of ascites. Tapping the ascites, with ultrasound guidance if the amount is subclinical, provides a specimen for cytology (Ch 20). If ascitic fluid is not available for cytology, transcutaneous needle biopsy of omental masses is usually possible under imaging guidance.

Aorta

An abdominal aortic aneurysm may present as an asymptomatic mass detected on clinical examination or as an unexpected finding on abdominal imaging. After an abdominal aortic aneurysm has been detected, it is important to measure its width (side to side), as the risk of sudden rupture of the aneurysm is related to aneurysm width. While a reasonable estimate of the width of an aneurysm can be made on clinical examination, ultrasound or CT scanning is more accurate. If the proximal extent of the aneurysm cannot be defined it may involve the renal arteries, making subsequent repair more difficult. This may be difficult to ascertain on physical examination and the width and proximal extent should always be checked on an abdominal ultrasound or CT scan. The management decision should be made by a vascular surgeon, but operative graft replacement or endoluminal grafting is usually indicated if the aneurysm is greater than 5.5 cm in diameter. If the aneurysm is 3–4 cm, monitor with ultrasound every 2–3 years; if 4–5.4 cm, monitor every 6 months. An expansion of over 0.5 cm in 6 months is another indication for surgery.

Other Investigations

Blood tests

An abdominal mass, whether truly asymptomatic or not, usually denotes a significant clinical problem. A faeces-loaded colon is an exception, though severe constipation can still be a significant clinical management issue. Simple haematological and biochemical screening is usually done early in the process of investigating an abdominal mass and usually includes a full blood count, liver function tests and serum levels of urea, creatinine and electrolytes. While these often provide useful information about systemic consequences of the mass and the process that has caused it, they are not diagnostic tests. More specific blood tests may be indicated once the organ of origin and the likely pathological process are better defined from the history and examination and the ultrasound or CT scans. With the diagnostic possibilities narrowed, a more appropriate selection of specific diagnostic tests can be made (see Table 19.6).

Table 19.6 Further evaluation of abdominal masses by blood tests

| Clinical diagnosis | Further blood test and rationale |

|---|---|

| Possible gastrointestinal malignancy | Tumour markers (Ch 17) including: |

Nuclear medicine

With the exception of PET, the use of radionuclide scanning in the anatomical and functional assessment and the diagnosis of abdominal masses has declined with the advent of cross-sectional imaging (ultrasound, CT and MRI scans). PET scanning is very useful in disease staging, in assessing responses to treatment and sometimes, when biopsy is impossible or inadvisable, for diagnosis. Radionuclide imaging still has an occasional place in the assessment of incidentally detected liver lesions (see Ch 26).

Key Points

Grover S.A., Barkuyn A.N., Sackett D.L. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have splenomegaly? J Am Med Assoc. 1993;270:2218-2221.

McGee S. Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Naylor C.D. The rational clinical examination. Physical examination of the liver. J Am Med Assoc. 1994;271:1859-1865.

Talley N.J., O’Connor S. Clinical examination. A systematic guide to physical diagnosis, 6th edn. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.