10

Palliative treatments of carcinoma of the oesophagus and stomach

Epidemiology and survival

Accurate information about the proportion of patients with oesophageal and gastric cancer who are treated with palliative intent is difficult to obtain. This largely reflects variations in the selection of patients for treatment. National audit data from England and Wales show that about 64% of new patients with oesophageal or gastric cancer undergo primary palliative treatment, although this varies between cancer networks and worldwide.1–3 Trials continue to examine the role of palliative chemotherapy or radiotherapy in oesophageal cancer, but currently there is no evidence to show a survival benefit when compared to best supportive care.4 The median survival is less than 8 months and few survive beyond 1 year. It is recommended, therefore, that treatment is tailored to the general status of the patient in order to reduce symptoms with minimal risks and side-effects.5

The resection rate for patients with gastric cancer is greater than that for oesophageal cancer (25%), probably because distal gastrectomy is still widely employed to overcome gastric outlet obstruction even in patients with advanced disease.1 Gastrojejunostomy (laparoscopic or open) or endoscopic stenting are also commonly performed if the tumour is very advanced or the patient frail. There is a lack of well-designed and conducted trials comparing distal gastrectomy with bypass or duodenal stenting, but systematic reviews comparing gastrojejunostomy with endoscopic stenting suggest that stent placement may be more favourable in patients with a very short life expectancy, although bypass is preferable in patients with a prolonged prognosis.6,7 The randomised trials examining these issues are often small, however, and well-designed studies are still needed. Palliative chemotherapy, either alone or in combination with biological therapies, may lead to improved survival in gastric cancer. A Cochrane systematic review shows that chemotherapy significantly increases survival in comparison with best supportive care and that combination chemotherapy improves survival compared to single-agent 5-fluorouracil (5-FU).8 It is also recommended that patients are tested for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) status and a monoclonal antibody (trastuzumab) be added in patients with HER-2-positive tumours.8,9 Despite these improvements in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer overall outcomes remain poor, with a median survival of less than 14 months.

Disease stage, age and general performance status influence outcomes and survival, although the effect of age may be largely due to more comorbidity in older patients.10 Another predictor of mortality is the length of the oesophageal tumour, mainly because this increases the likelihood of nodal involvement with large tumours.11 All these factors need to be taken into consideration when planning treatment.

Patient selection and multidisciplinary teams

Since the introduction of the National Health Service Cancer Plan in the UK in 2000, treatment decisions for patients with cancer are mandated to be made within the context of a multidisciplinary team.12 Guidelines for the constitution and processes for upper gastrointestinal multidisciplinary teams have been published and national peer review processes audit team working.12,13 Teams consist of core members, specialist nurses, gastroenterologists, oncologists, pathologists, radiologists, administrators, palliative medicine experts and surgeons. Additional members may include cytologists, dieticians and researchers from clinical trials units. The aim of the team is to review available evidence for each new patient and make optimal treatment decisions. Evidence includes information about the cell type, disease stage, patient comorbidity and choice, and expert discussion of best available treatments. Although team working has been widely implemented across the UK and is recommended by some continental European centres, in North America a similar role of ‘tumour boards’ is not mandatory within cancer care.14 Currently, evidence to support team working is sparse, based upon longitudinal or retrospective case series. It is also uncertain how to best evaluate the quality of multidisciplinary teams because outcomes are dependent upon so many variables. It has been suggested that monitoring implementation of team decisions further evaluates team working. In one centre it has been shown that 15% (95% confidence interval (CI) 10–20%) of team decisions change after the meeting.15 The most common reason cited for changing team decisions was lack of available information about patient choice and comorbidity. There is also uncertainty whether upper gastrointestinal multidisciplinary teams should routinely discuss patients who develop disease recurrence following radical treatment.16 If this becomes mandatory in the UK the workload of teams would increase; however, patients with recurrence should be offered the full range of palliative treatments and so this requires further consideration. Team working is an area that is likely to develop over the next decade; professionals may need training in team-working skills and the infrastructure to support these processes is required.17

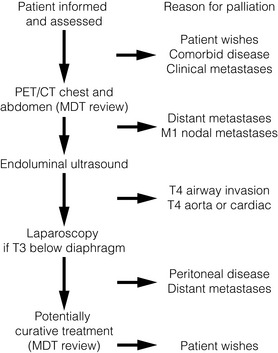

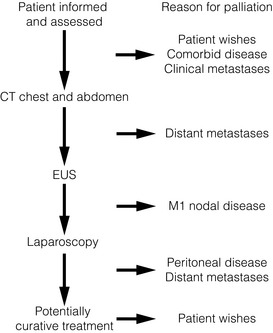

After establishing a diagnosis, new patients require careful assessment to decide whether treatment should be directed towards attempting a cure, or if palliation of symptoms is more appropriate. Careful patient selection has been shown to significantly influence results. Principal factors to consider are the type and stage of the tumour, physical and psychological well-being of the patient, and knowledge of patient preferences. Decisions should be considered in the knowledge of treatment outcomes, including impact on patients’ health-related quality of life. Figs 10.1 and 10.2 illustrate pathways that can be used to select patients for palliative treatment.

Figure 10.1 Algorithm for selection for palliative or curative treatment of oesophageal and junctional tumours. CT, computed tomography; MDT, multidisciplinary team; PET, positron emission tomography.

Figure 10.2 Algorithm for selection for palliative or curative treatment for cancers of the gastric body or antrum. CT, computed tomography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasonography.

Fitness for treatment

The place of oesophagectomy in many older patients is often easily settled because of general debilitation or multiple coexistent medical problems. Age in itself does not preclude octogenarians from surgery, but in most series older patients are carefully selected. In general, patients who are not fit enough for oesophagectomy are also unable to tolerate a radical course of radiotherapy or definitive chemoradiation. On the whole, surgery for gastric tumours is better tolerated than oesophageal surgery by the elderly population, but patients still require careful preoperative assessment before undergoing major resection. Anaesthetic assessment for surgery is considered in more detail in Chapter 4.

Patient preferences and information provision

Information about the diagnosis and prognosis of oesophageal and gastric cancer should be offered to all patients and it is essential that a nurse specialist is involved in this process whenever possible. The volume and type of information required will vary between individuals, although evidence from studies of patients’ information needs performed in other disease sites generally shows that patients wish to have as much information as possible and prefer the information to be provided by a health professional, as well as in other forms such as a booklet or CD-ROM.17 It is necessary to inform patients of the potential treatments and alternatives together with treatment-related benefits and risks, both in the short and long term. Surveys of patients’ information needs also show that information about impact on health-related quality of life is considered important to patients during treatment decision-making.18 Ensuring that consultations provide this information in a way that is understood is difficult and requires that professionals are trained. In the UK it is recommended that all specialist cancer teams undergo training in advanced communication skills.19 All clinicians will be faced with patients who demand every small chance of cure, despite its risks, and others who wish to receive minimal, dignified intervention. Communicating outcomes, providing adequate information and listening to patients’ views is necessary so that patients and their families have access to as much information and support as required.

Symptoms and signs of advanced oesophageal and gastric cancer

Tumours of the gastric body and antrum

Gastric cancer commonly has an insidious presentation and some patients have few symptoms. Slow blood loss may eventually result in symptoms of anaemia. Haematemesis is a rare first presentation. Vague upper gastrointestinal problems, such as epigastric discomfort, early satiety and gastro-oesophageal reflux, are common. Tumours of the distal stomach cause outlet obstruction and patients describe epigastric fullness, reflux and nausea, finally leading to effortless vomiting. The presence of an epigastric mass, supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, jaundice, ascites or pleural effusions all reflect advanced disease. Less commonly, bony pain and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure are seen related to metastatic spread. Symptoms of oesophageal and gastric cancer are listed in Box 10.1.

Palliative treatments for cancer of the oesophagus and gastric cardia

A variety of approaches are available for the palliation of advanced tumours of the oesophagus and gastric cardia. These include rigid plastic tube insertion, self-expanding metal stents (SEMS), brachytherapy, external beam radiotherapy, chemotherapy, chemical and thermal ablation, palliative resection (for gastric cancer) and bypass surgery either as single or combination treatment modalities. These different treatment modalities can treat and palliate the cancers and therefore there is no longer a role for palliative surgery for oesophageal cancer, which has a major detrimental impact on patients’ quality of life.20 Generally, patients undergoing palliative surgery do not have sufficient time to recover from the operation before they experience symptoms of metastatic disease. Historical data also show that palliative resection is associated with high perioperative mortality and morbidity rates. It is possible that the improved surgical techniques and perioperative care may mean that minimal access surgical resection may in certain situations be suitable for the palliation of oesophageal cancer; however, well-designed studies are needed to corroborate this. Evidence for the effectiveness of non-surgical interventions for the palliation of malignant dysphagia in the treatment of primary oesophageal cancer is summarised in a recent Cochrane review that includes 40 studies.21 Overall, it concluded that SEMS insertion is safe, quick and effective in palliating malignant dysphagia compared to other modalities. High-dose intraluminal brachytherapy may be a suitable alternative and provide additional survival benefit and quality of life. The individual studies examining endoscopic methods of relieving luminal obstruction are considered below, with other sections concentrating on treatments for palliation of other common problems in oesophageal or oesophagogastric junctional cancer:

1. Endoscopic methods of relieving luminal obstruction.

2. Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, chemoradiotherapy and monoclonal antibody treatments.

3. Management of aero-digestive fistulas.

The endoscopic relief of luminal obstruction

Malignant dysphagia may be relieved by stent insertion, brachytherapy, external beam radiotherapy, chemotherapy or tumour ablation with photothermal, photodynamic therapy, or by the injection of cytotoxic substances.20 Many modalities are complementary and SEMS insertion is safe, effective and quicker in palliating dysphagia compared to other modalities. No one method or combination is greatly superior to the rest in terms of relief of dysphagia, although some evidence is emerging to show better long-term relief of dysphagia with high-dose intraluminal brachytherapy. This might provide a suitable alternative and may provide additional survival with a better quality of life compared to metal stent placement.22 Historically, dilatation was advocated for the palliation of malignant dysphagia and rigid plastic tubes were inserted following this. Because of the short-lived benefits of dilatation alone and the associated risks of perforation, its use nowadays is reduced to that of a preliminary measure before definitive management of dysphagia. Minimal oesophageal dilatation may be performed to allow insertion of an SEMS or to place a brachytherapy bougie. Guidelines on the use of dilatation in clinical practice recommend careful preparation, polyvinyl wire-guided bougies or hydrostatic balloons.23 Strictures with severe narrowing and angulation are best negotiated under X-ray screening.

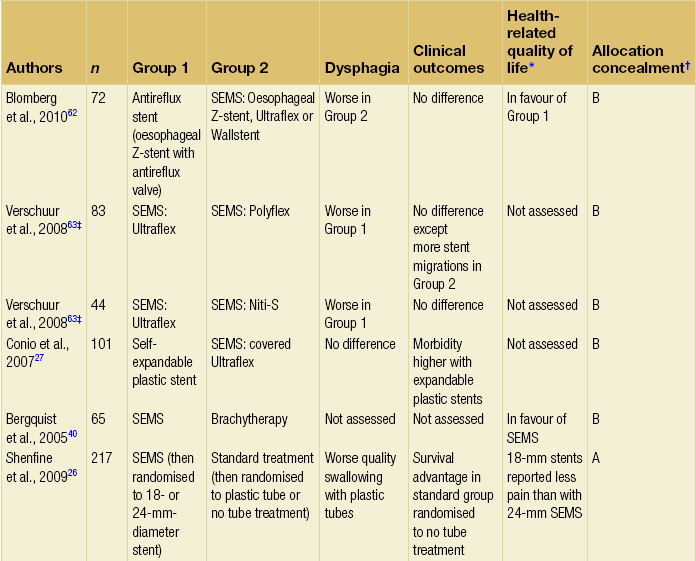

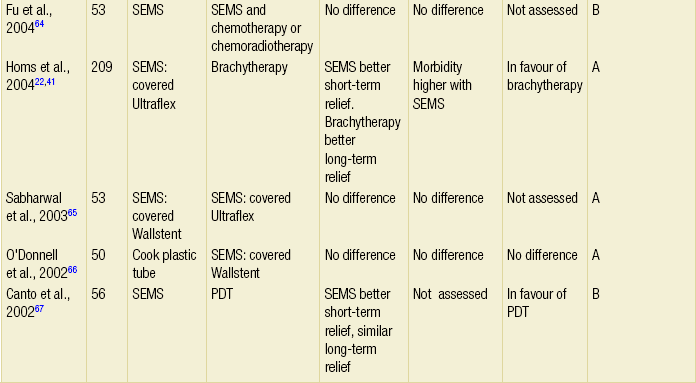

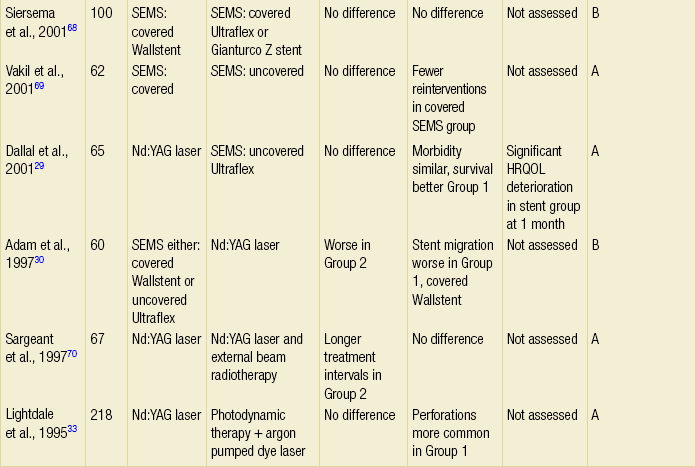

The majority of randomised trials evaluating palliative treatments for dysphagia have been small and single-centred, and may therefore have lacked power to detect differences between treatment arms. Table 10.1 summarises the randomised controlled trials published before the end of 2011, evaluating interventions of the palliation of malignant dysphagia. The table includes only trials that randomised more than a total of 50 patients, excluding smaller studies because they are less likely to influence practice. Even within the included studies, eight (50%) may be at risk of selection bias because methods used to conceal the allocation sequence were unclear (i.e. intervention allocations could have been foreseen before or during enrolment).

Table 10.1

Prospective randomised controlled trials of endoscopic palliation of malignant dysphagia (n > 50)

Note: 30-day mortality rates were similar in all of the above trials.

*Health-related quality-of-life results in article reported from a valid multidimensional questionnaire.

†The risk of bias in the trial was judged as A = low, B = unclear or C = high, using the Cochrane risk of bias tool assessing allocation concealment.71 The tool allows an author to judge whether the randomisation process described in the study has clear evidence that the treatment allocation was concealed to the person randomising the patient before the patient is entered into the study.

‡This randomised controlled trial had three treatment arms and subsequently two comparisons.

Intubation

Intubation is probably the most widely used form of palliation of malignant dysphagia at present and allows rapid relief of dysphagia with associated low morbidity. Prostheses may be placed endoscopically, radiologically or surgically at laparotomy, although there is little place for open insertion of a prosthesis when a tumour is unexpectedly found to be irresectable because endoscopic insertion is safer and has fewer complications. Self-expanding metal stents are now routinely employed for this purpose and plastic rigid tubes are generally no longer in use.21,24–26

Self-expanding metal stents (SEMS): The design of SEMS has evolved since they were first introduced for the palliation of malignant dysphagia in the early 1990s with the introduction of covering and also fixtures to allow endoscopic stent removal. They are made from a flexible metal mesh that expands after deployment for up to 48 hours, leading to rapid relief of dysphagia and creation of an internal luminal diameter of 16–25 mm. Early disadvantages of tumour ingrowth and stent migration have been largely overcome by newer materials and designs, although migration may still occur when stents are placed at the oesophagogastric junction. Although initially stents were expensive (about £500–800), the cost is now reducing. Current design developments are centred upon using expandable plastic rather than metal to reduce the manufacturing costs, and developing removable stents and possibly dissolvable stents to use in temporary settings.27 Stents nowadays, therefore, may be fully or partially covered (partially covered self-expanding metal stents, PCSEMS). Several studies have investigated the addition of a valve in the distal part of the stent to reduce acid reflux.28

Method of insertion: Self-expanding metal stents may be inserted endoscopically or radiologically. There are several designs with very similar delivery devices. The Ultraflex Esophageal Stent (Boston Scientific Inc.) is made of an alloy of titanium and nickel and has a shape ‘memory’ as well as superelastic behaviour. It is loaded in a small-diameter delivery catheter, constrained in a compressed form by a double plastic membrane. During expansion the stent shrinks by approximately one-third. It is available either uncovered or partially covered. The design incorporates a proximal flare for secure placement and to reduce the possibility of food entrapment. The conical ‘Flamingo’ Wallstent is designed to reduce problems with migration, and the proximal and distal 1.5 cm of the stent remain uncovered. It may be recovered during deployment and repositioned, provided less than 50% of the endoprosthesis has been released. The Gianturco Z stent also uses stainless steel and it is entirely coated with a polyethylene film. It has long wire hooks at its mid-portion to facilitate anchoring. Unlike the Ultraflex and Wallstents it undergoes very little shortening upon release. A ‘windsock’ design to reduce the possibility of gastro-oesophageal reflux is available. Other stents are variations on these basic designs. Comparative studies show that reintervention rates for tumour ingrowth are higher with uncovered than covered stents. Other comparative studies of SEMS show conflicting results and although these trials may have design weaknesses, there is currently no good evidence that one design is superior to another in terms of morbidity or relief of dysphagia.

Preparation: Endoscopic prosthesis insertion is usually possible under intravenous sedation, although some endoscopists continue to use general anaesthesia. Routine monitoring is required with intravenous sedation, as is continual attention to the airway. Saliva and regurgitated fluids should be constantly removed to prevent aspiration during the procedure.

Endoscopic insertion with fluoroscopy: After endoscopic assessment and measurement of the tumour, a guidewire is passed into the stomach (after successful negotiation of the tumour with the endoscope or under fluoroscopic control). Occasionally, dilatation may be required to a minimum of 10 mm before passage of the delivery system over the guidewire. The proximal and distal extents of the tumour may be marked with radio-opaque skin markers or the tumour limitations injected with contrast. The slim delivery device is advanced over the guidewire until the radio-opaque markers of the compressed stent are correctly aligned with the tumour. Once in position the stent is deployed. It is possible to reposition some of the stents after partial deployment. The guidewire and delivery device are then carefully removed under fluoroscopic guidance. After release of the stent, the endoscope may be reinserted to check the final position. Immediate balloon dilatation is recommended to improve expansion and prevent early migration, but may still be performed up to several days after stent insertion.

Radiological insertion: Morphological imaging of the malignant stricture with oral contrast is performed prior to stent insertion. This assesses length and position of the tumour. A fine steerable catheter is then negotiated over a guidewire through the stricture to the stomach and skin markers aligned. The proximal and distal ends of the tumour are marked (similar to endoscopic positioning). Balloon dilatation to 10–15 mm may be performed if the stricture is very narrow. The stent insertion device is then passed safely and positioned radiographically over the guidewire and released according to the type of stent.

Postoperative management: After stent insertion the patient must be instructed to sit upright. Oral fluids are usually allowed the same day unless there is concern about complications or symptoms or signs of perforation. Clinical and radiological examination may be performed to exclude perforation before oral fluids are commenced. Patients should receive written dietary information with advice to chew food carefully and drink regularly during and after meals. A daily intake of 10 mL hydrogen peroxide (20 vol.) is sometimes recommended.

Complications: Even in experienced hands, intubation with SEMS has a procedure-related mortality of about 1–2% and early complication rates of between 0% and 30%. Complications are listed in Box 10.2.

1. Malposition of the stent may require insertion of a second or even third stent (if the tumour is long). This may overlap the malpositioned stent to adequately cover the tumour.

2. Incomplete stent expansion and early dysphagia may require balloon dilatation if no improvement is seen within 48 hours.

3. Early stent migration. This occurs in about 1% of patients and is more prone in stents placed at the oesophagogastric junction than in stents with both ends anchored within the oesophagus. Endoscopic retrieval may be performed safely, especially with the newer devices. Stents that have migrated into the stomach may also be safely left as they rarely obstruct the pyloric channel or cause intestinal perforation.

4. Oesophageal perforation is the most serious complication and is more likely if the stricture has been dilated before stent insertion, there has been prior use of radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, if the tumour is sharply angulated or if it extensively encases the oesophagus. Rapid development of subcutaneous emphysema, severe pain, radiological evidence of pneumomediastinum, air under the diaphragm or a pleural effusion should all raise suspicion. The extent of the leak is confirmed by contrast radiography. The most appropriate form of therapy depends on the time of detection and the extent of the leak. If recognised at endoscopy, the insertion of the prosthesis itself may seal off the perforation and prevent mediastinitis. Alternatively, the procedure may be abandoned and conservative treatment undertaken. This involves administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, cessation of oral intake and feeding either parenterally or by jejunostomy. An intercostal drain may need to be inserted if there is evidence of pleural contamination. Specific management of this serious complication is covered in detail in Chapter 19.

5. Severe upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage occasionally occurs. This is difficult to treat, and only supportive measures may be possible.

Late complications: Long-term problems occur in at least 20% of patients and are most frequently related to eating. Problems often require hospital admission, further endoscopic manoeuvres and occasionally replacement of the prosthesis.

1. Prostheses may block because of tumour overgrowth at either end of the stent or tumour ingrowth through the metallic stent latticework if an uncovered design is used. This leads to recurrent dysphagia and occurs in 5–30% of patients. Tumour ingrowth is best managed with laser, argon-beam coagulation or photodynamic therapy. Overgrowth at either end of the stent may be successfully treated with placement of a second stent.

2. Food bolus obstruction occurs in metallic stents despite their wide diameter. Spontaneous resolution can occur or endoscopy may be required to displace the impacted food bolus into the stomach.

3. Reflux of gastric acid occurs in all patients whenever the tube crosses the gastro-oesophageal junction. It may lead to oesophagitis and occasionally benign stricture formation above the tube. This can be controlled by conservative measures, dilatation and acid suppression therapy. The use of a stent with an antireflux valve may reduce reflux symptoms.

4. Pressure necrosis and late oesophageal perforation leading to mediastinal fistulation has been reported.

5. Stents can fracture or twist, leading to serious morbidity. These are rare problems as most patients do not live long enough. Operative removal of these tubes is only very occasionally required.

6. Eating difficulties exist due to incomplete relief of dysphagia. Once a prosthesis is in place all food must pass through a tube with a fixed diameter. Patients therefore need appropriate nutritional support and advice.

Manufacturers continue to develop new designs to decrease the risk of migration, increase the ease of insertion and enable stents to be repositioned or extracted. A new self-expanding plastic stent (SEPS) prosthesis has been evaluated but may lead to particular problems of stent migration. However, it is likely that future developments will overcome these issues.27 Despite the associated morbidity with stent insertion, the immediate relief of dysphagia in one endoscopy session has made intubation an attractively simple palliative treatment, particularly for patients with poor performance status whose life expectancy is short.

Laser treatment

Endoscopic technique: Laser treatment is usually carried out with intravenous sedation, although some centres use a rigid endoscope requiring general anaesthesia and endotracheal intubation. Those in favour of a rigid scope believe its advantages are that it allows better suction of fluid, smoke and debris, with improved visualisation of the tumour. If a malignant stricture is negotiable, the laser is first applied to the distal end of the tumour. The scope is then withdrawn in a circular fashion into the more proximal tumour. If complete obstruction is encountered, tumours can be vaporised in the antegrade direction or first dilated to allow passage of the endoscope. Antegrade therapy may be more dangerous because information about the luminal axis is lacking and the area first treated rapidly becomes oedematous, thus impairing visualisation and access more distally.

Early complications: The incidence of major complications and mortality (which is in the region of 1–5%) was usually lower for laser destruction than endoscopic intubation with rigid plastic stents. Few studies have compared laser treatment with metal stents (Table 10.1). Early complications after laser treatment are listed in Box 10.3.

1. Chest pain may result from extensive mucosal burning. It is common but not severe.

2. Oesophageal perforation is less common following laser recanalisation than intubation with a rigid endoprosthesis. The risk is about 5% and is said to be related to predilatation rather than a direct complication of the laser treatment.

3. A benign pneumoperitoneum or pneumomediastinum is sometimes detected by chest X-ray after laser treatment. This is thought to be related to jets of coaxial gas passing through abnormal, often necrotic, tumour tissue. Patients rarely have symptoms. Contrast studies do not show a leak and patients usually make an uneventful recovery.

4. Gastric distension as a result of carbon dioxide infusion can be quite uncomfortable despite adequate decompression. The pain is visceral in nature and may be confused with chest pain from excessive mucosal burning.

5. Haemorrhage after laser treatment is rare, occurring in about 1%.

Late complications: Late complications frequently occur following laser destruction and require repeated endoscopic treatment.

1. The main problem is tumour recurrence. Patients require about monthly treatment sessions. It is perceived by the medical profession that this is burdensome and disruptive, but there have been few studies that have objectively measured patients’ views about this matter. Some may feel that continued hospital contact contributes to their sense of well-being.

2. Delayed laser-associated benign strictures can occur in up to 20% of patients. They require repeated dilatation and occasionally stent insertion.

3. Persistent dysphagia for solids. Laser treatment may recanalise 90% of all stenoses, but a wide luminal diameter does not necessarily equate to normal swallowing. Distal tumours may cause ‘pseudoachalasia’ that impairs swallowing. Residual intramural tumour may cause impaired oesophageal body motility and, together with progressive cachexia, may make it impossible for some patients to take solid foods again.

Combination laser treatment: In view of the varied responses with laser treatment alone, means of improving the efficacy of laser treatment by increasing the period between laser therapy and symptomatic relapse have been explored through combination treatments. Laser therapy can be combined with external- or internal-beam radiotherapy to prolong the interval between treatments, although the patient must attend for radiotherapy, which does increase hospital attendance. Intraluminal radiotherapy is useful for treating mural invasion following laser debulking of the tumour.

Thermal recanalisation or stenting?

Although laser therapy is rapid, safe and effective, and may have superior relief of dysphagia compared to rigid intubation, it also has drawbacks related to the need to attend hospital on a regular basis and the capital cost of the equipment. It may be preferable for non-circumferential, polypoid or exophytic tumours, but it is not suitable for patients with a fistula, an extrinsic lesion causing oesophageal compression, or patients with a diffuse subepithelial tumour. Two randomised controlled trials that included 125 patients comparing SEMS with thermoablative therapy (predominantly laser) showed no evidence to suggest that either modality is different in improving dysphagia, the interval to recurrent dysphagia or procedure-related mortality.29,30 It is noted, however, that both procedures have certain adverse effects that are more common in each group. Laser may therefore increasingly be viewed as a complementary rather than competing palliative treatment, to deal with tube overgrowth or ingrowth or local recurrence after surgery.

Argon-beam plasma coagulation

High-frequency diathermy electrocoagulation has become widely used for surgical haemostasis and to ablate tumour tissue. The argon-beam coagulator utilises a jet of ionised argon gas to limit conduction of high-frequency electrical energy to the desired point, i.e. tumour and unhealthy tissue. This is readily applied through an endoscope. Once the surface of the tumour has been coagulated and dried, the electrical current passes through to an adjacent area. Unlike laser light, the argon beam will arc to the nearest point of contact. The depth of extension is minimal (2–3 mm) and this reduces the risk of perforation. The gas flow is high, which means that regular aspiration is required to prevent gastric distension. It is not expensive and operator confidence is high, given the low risk of perforation. Because of these pragmatic features it has largely replaced laser treatment as a primary debulking treatment.31 As with laser treatment, it is time-consuming and there is a need for repeated treatments.

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an investigational treatment that modifies conventional laser treatment. It uses a selective technique that targets tumour tissue and limits damage to adjacent tissue. It essentially has three elements: light, a photosensitising drug (a haematoporphyrin derivative) and oxygen. The drug acting as a photosensitiser is injected intravenously 3–4 days before irradiation of the tumour. Laser light (administered endoscopically) then activates the drug within the tissue. Once stimulated, the photosensitiser interacts with oxygen to create a highly reactive oxygen species that is cytotoxic. Retention of the photosensitiser is longer in dysplastic or frankly neoplastic than normal tissues, at a ratio of about 2:1. Damage to normal tissue heals by regeneration.32

Clinical indications: The role of PDT in palliative treatments is yet to be determined and is likely to be small. It may be used to treat patients with small mucosal tumours (uT1, N0) who are unfit or who do not wish to undergo major surgery (see Chapter 6), or it can be used on larger inoperable lesions where other treatments have failed. Two prospective randomised studies have compared PDT with laser therapy.33,34 There was no evidence to suggest differences between PDT and laser treatment in dysphagia or 30-day mortality and equivocal evidence that PDT decreased the need for repeated endoscopic interventions compared to laser treatment.

Complications: A number of specific complications have been recognised. The activated photosensitiser creates an iatrogenic porphyria, which may persist for up to 6 weeks after injection of the drug and leads to skin photosensitivity. Patients are advised to avoid sunlight. Perforation and fistulas may occur as well as oesophagitis leading to stricture formation. PDT has yet to enter widespread clinical use, partly because of cost. New photosensitisers with shorter durations of action may make the treatment more acceptable. At present, there are no data to support PDT as first-line palliative treatment, but it may be considered for high oesophageal tumours, for salvage treatment if stents have migrated or for stent over/ingrowth.

Bipolar electrocoagulation

Bipolar electrocoagulation (BICAP) is another thermal endoscopic treatment that has been used to relieve dysphagia.35 Usually 2–4 mm of coagulation occurs at the tumour surface and one or two treatment sessions are required to treat the entire tumour. Although dysphagia may be partially relieved, problems with perforation, fistula formation, strictures and bleeding have occurred, and the technique has never been widely used.

Chemically induced tumour necrosis

The use of intralesional injection of alcohol (usually ethanol) to induce tumour necrosis is a simple and readily available palliative treatment, suitable for exophytic tumours and tumours in the proximal oesophagus.36,37 It may also be used to control haemorrhage from bleeding tumours.

Endoscopic technique: Patients require intravenous sedation and flexible endoscopy. A sclerotherapy needle is used to inject 0.5- to 1-mL aliquots of alcohol into the protuberant part of the tumour. Endoscopic observation of the tumour blanching and swelling confirms needle position. In patients with long tumours it is best to start injections distally so that induced oedema does not impede the passage of the endoscope. There is no limit to the total volume injected in one session (1–36 mL have been reported). Dilatation is needed if the endoscope is unable to traverse the stricture. Several treatment sessions may be required to improve swallowing, but it usually does so within a week of injection.

Outcome: An improvement in dysphagia score is reported in most patients after treatment with absolute alcohol, although it may be made temporarily worse because of initial tumour oedema and swelling. Retrosternal chest pain and low-grade pyrexia may occur. Perforation and fistula formation have been reported.38 The pattern of necrosis may be unpredictable and the main disadvantage is the need for repetitive treatments.

External beam and intracavity radiotherapy

External beam radiotherapy

Complications: Side-effects are common and often serious, particularly if initial treatment seems successful: pulmonary fibrosis, fistula and benign stricture formation have all been described. Data from the 1970s show that less than 40% of patients experience acceptable palliation of dysphagia with external beam radiotherapy. Problems with recurrent dysphagia, as a result of cicatricial narrowing of the oesophagus, also occur.39 As a single modality it has probably been superseded by intracavity irradiation or combination treatment. A new NIHR HTA (National Institute of Health Research, Health Technology Assessment) trial comparing the addition of external beam radiotherapy to SEMS is just starting in the UK. This will provide clarity about whether this leads to improved control of dysphagia in patients with a poor life expectancy.

Brachytherapy (intracavitary irradiation): The development of the Selectron (Nucleotron, Zeersum, the Netherlands) remote control after-loading machine has generated considerable interest in recent years because it places the radiotherapy source close to the tumour and maximises the tumour radiation dose. It is a simple and safe procedure, and there is no radiation exposure to staff. The brachytherapy applicator, only 8 mm in diameter, is passed over an endoscopically placed guidewire and positioned in the tumour by fluoroscopy. This is immobilised at the mouth or nose. The patient is then transferred to a protected treatment room and connected to the Selectron machine. A microprocessor controls the pneumatic transfer of caesium-137 pellets down a flexible tube inserted into the applicator. The optimal dose is unknown and varies from 15 to 20 Gy to a depth of 1 cm in single or multiple fractions. Treatment may be repeated on alternate days leaving the nasogastric tube in situ or replacing it as necessary, although it is usually given as a single-dose fraction of 10–15 Gy. It is necessary to precisely map the tumour by endoscopy, fluoroscopy or computed tomography, and planning aims to incorporate a few centimetres of normal oesophagus at either end. The great merit of brachytherapy is that the radiation dose is highest to the tumour while adjacent normal tissues are relatively spared. It can be used in combination with other treatments.

Relief of dysphagia and patient-reported outcomes: Two well-designed randomised trials have been reported that compare single-dose brachytherapy (12 Gy) with SEMS (Ultraflex covered stent) in patients not suitable for curative treatment.22,40,41 The main end-point of these trials was dysphagia. Results showed that SEMS provided better short-term relief of dysphagia but was associated with increased morbidity. Longer-lasting relief of dysphagia was achieved in the brachytherapy group. In the larger trial, survival was similar in both arms (median survival 155 days (95% CI 127–183 days) after brachytherapy and 145 days (95% CI 103–187 days) after stent placement), but morbidity was significantly higher after stent insertion than after brachytherapy. Major complications included perforation, haemorrhage and fistula formation. Major haemorrhage occurred more significantly after metal stent insertion. Other complications include the development of post-irradiation strictures or tracheo-oesophageal fistula. This trial also included a robust assessment of health-related quality of life and costs. Health-related quality-of-life differences between treatments were initially small but increased over time. Indeed, for emotional, cognitive and social function, differences in effect over time were statistically significant and differences were also seen in the dysphagia scale.41 There were only minor differences in costs between the two treatments. The authors of the trial concluded that brachytherapy should be the primary treatment for palliation of dysphagia from oesophageal cancer.

Palliative chemotherapy or combination chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal cancer

The role of palliative chemotherapy for oeophageal cancer remains ill defined. The aim of treatment is to control local and distant tumour to improve quality of life and prolong survival. A recent Cochrane systematic review included only two randomised controlled trials, with a total of 42 patients, comparing chemotherapy with best supportive care for metastatic oesophageal cancer.4 Median survival in the intervention group was 6 months compared to 3.9 in the control group and there was no difference in quality of life (although only one aspect, oral intake, was measured); the small number of included patients means robust conclusions cannot be drawn. In the five randomised trials assessing different chemotherapeutic regimes in 1242 patients, two compared monotherapy with combination treatments and found non-significant improved response rates in the latter group, with similar survival. The remaining three trials compared different combination therapies; no consistent benefit to any specific regimen was observed and it was not possible to perform a formal pooled analysis. Although quality of life was measured, response rates were very poor and validated questionnaires designed specifically for oesophageal cancer patients were not used. There is therefore a need for well-designed trials to assess the effect of palliative chemotherapy on survival and quality of life in patients with advanced oesophageal cancer.

It is possible that combination chemoradiotherapy may improve response rates and survival, although evidence is also limited. Additionally, there is a lack of evidence to support the role of second-line chemotherapy, although a current trial is investigating the use of gefitinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and results are awaited.43 Patients suitable for palliative chemotherapy often require attention for nutritional needs. If the initial course of chemotherapy can be tolerated and a response achieved, it is possible that relief of dysphagia will occur and last for some months before further progression is experienced.

Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in the palliation of oesophageal cancer

Growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) and transforming growth factor α (TGFα) that bind and activate the erbB1 receptor, also known as the EGFR, are known to be involved in the mitogenic process in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer of the oesophagus. EGF over-expression has been found in Barrett’s oesophagus and in oesophageal cancers, and a high level of EGFR expression is associated with poor prognosis.44 Both phase I and II trials have used small-molecule inhibitors to target EGFR and data are encouraging in both oesophageal cancer cell types.45–48 In the UK, the COG (Cancer Oesophagus Gefitinib) trial has now completed recruitment of over 400 patients and results will be available in 2013.43

Aero-digestive fistulas

Aero-digestive fistulas cause paroxysmal coughing fits, aspiration and, if untreated, eventually death from recurrent chest infections. They occur in about 5% of patients with oesophageal cancer, either because of spontaneous necrosis of the tumour and/or local nodes through the oesophageal wall into the bronchial tree, or as a result of treatment. Such fistulas are difficult to treat and life expectancy is usually short. The creation of a cervical oesophagostomy and gastrostomy may relieve symptoms, but is not usually appropriate. Palliative bypass surgery with stomach or colon for interposition is highly invasive and is also not generally recommended because of the poor general health and prognosis of patients in these situations. Endoscopic insertion of a prosthesis is the treatment of choice, although results following the use of rigid prostheses have not been encouraging, despite the availability of modified cuffed prostheses. The use of covered metal stents to seal aero-digestive fistulas seems to be a more promising development, although no randomised trials have been performed.49 Fistulas close to the cricopharyngeus are particularly difficult to manage. In this situation simultaneous tracheal and oesophageal stenting may be performed. The possibility that an oesophageal prosthesis may cause significant airway compression should always be considered for tumours in the upper half of the oesophagus and particularly when a fistula of the airway is known or suspected. Preliminary bronchoscopy may clarify this and indicate that tracheal stenting may be preferable to oesophageal stenting, or at least should be performed before oesophageal stenting. Tracheal stenting may also be necessary before commencing chemoradiation treatment for T4 tumours close to, but not actually invading, the airway.50 At present the role of chemotherapy or radiotherapy in this regard needs further evaluation. The endoscopic placement of fibrin tissue glue may be worthwhile where stenting is not achievable.

Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy

Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy caused by tumour infiltration results in eating difficulties, a weak voice, poor cough and repeated chest infections because of aspiration pneumonia. Patients are usually hoarse and complain of swallowing difficulties in the oropharyngeal phase. Coughing and a sensation of choking are typical on consuming solids and liquids. The diagnosis is confirmed by laryngoscopy. Endoscopy may be required to exclude other problems contributing to dysphagia. Aspiration can be confirmed during the pharyngeal phase of swallowing on barium studies. The left nerve is more commonly involved because of its intrathoracic course. Teflon injection to re-establish glottic competence should help swallowing, speech and problems with coughing. In a series of 15 patients, all improved except one, who developed stridor and required emergency tracheostomy.51 Recurrent laryngeal nerve damage at the time of oesophagectomy usually causes a temporary paralysis that resolves within 6 weeks.

Palliative treatments of tumours of the gastric body and antrum

Chemotherapy for advanced gastric and oesophagogastric cancer

Systemic chemotherapy is the main treatment option for patients with inoperable gastric tumours. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials on first-line chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer has summarised current knowledge.8 Palliative chemotherapy offers survival benefits compared with best supportive care (hazard ratio 0.37, 95% CI 0.24–0.55), which can be interpreted as an improvement in median survival from 4.3 months (best supportive care) to 11 months (chemotherapy). Combination versus single agents also confers survival advantages (hazard ratio 0.82, 95% CI 0.74–0.90). Combinations of 5-FU/cisplatin/anthracycline were found to significantly benefit overall survival compared with 5-FU/cisplatin (hazard ratio 0.77, 95% CI 0.62–0.95) and, similarly, benefits were found when comparing 5-FU/cisplatin/anthracycline with 5-FU/anthracycline (epirubicin). Although the survival benefit of oral 5-FU (capecitabine) compared with intravenous formulations did not reach statistical significance in this review, another meta-analysis confirmed the non-inferiority of capecitabine52 and a further review found significant survival benefits.53 This oral preparation is advantageous as it eliminates the need for continuous infusions and associated risks of long-term venous lines, and has been approved by NICE for use in these patients. Evidence also indicates that oxaliplatin is non-inferior to cisplatin in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer.8,54 Epirubicin, cisplatin/oxaliplatin and capecitabine is therefore recommended to achieve best survival results and minimise rates of toxicity. More recently, the use of monoclonal antibodies has been examined in the context of advanced gastric cancer and in a phase III study median overall survival was 13.8 months (95% CI 12–16 months) in those assigned to trastuzumab (herceptin) plus chemotherapy compared with 11.1 months (95% CI 10–13 months) in those receiving chemotherapy alone (hazard ratio 0.74, 95% CI 0.60–0.91).9 It is therefore also recommended that patients are routinely tested for HER-2 overexpression and potentially receive trastuzumab in combination with cisplatin and capecitabine. To date, effectiveness of trastuzumab has not been assessed using any other drug combinations.

Gastric outlet obstruction

Patients with non-resectable distal lesions may undergo gastrojejunostomy. The loop of jejunum is anastomosed close to the greater curve of the stomach. There is little consensus regarding anterior or posterior loops. The latter may theoretically be more prone to recurrent obstruction due to proximity to the tumour. The Devine exclusion bypass operation for inoperable antral tumours was thought to increase survival by preventing recurrent tumour obstructing the gastrojejunostomy.55 There is some evidence that laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy for palliation of incurable gastric outlet obstruction causes less morbidity than standard open surgery. Systematic reviews of the role of stents versus gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction suggest that stent placement may be associated with more favourable results in patients with a relatively short life expectancy and that gastrojejunostomy was the recommended palliative treatment in patients with a better prognosis.6,7

Chronic bleeding

Surgery remains a useful therapeutic manoeuvre to palliate the symptoms and problems of chronic blood loss from gastric tumours. Laser therapy can successfully achieve haemostasis in bleeding gastric malignancies and there are increasing reports of argon-beam coagulation to limit bleeding from gastric tumours.56 Both methods require repeated hospital admissions. Radiotherapy may also be used to control chronic bleeding from gastric tumours, although there are no published data to support this practice.

Summary

There remains a need to define outcomes for patients with inoperable malignancies of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Although it would be useful to standardise dysphagia scores and improve audit, in the palliative setting the most important outcome should be patients’ assessment of benefits of treatment. The use of self-report quality-of-life questionnaires in clinical practice will provide such data, although at present these are mainly research tools.57–59 The role of the specialist upper gastrointestinal nurse to support patients undergoing palliative treatment and to provide nutritional support is increasing, and links between palliative care and upper gastrointestinal cancer teams need to be well established and used.60,61

References

1. National Oesophago-Gastric Cancer AuditThird annual report. London: The NHS Information Centre, 2010.

2. Ajani, J.A., Barthel, J.S., Bentrem, D.J., et al, Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011;9(8):830–887. 21900218

3. Yada, I., Wada, H., Shinoda, M., et al, Thoracic and cardiovascular surgery in Japan during 2001: annual report by the Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;51(12):699–716. 14717431

4. Homs, M.Y., van der Gaast, A., Siersema, P.D., et al, Chemotherapy for metastatic carcinoma of the esophagus and gastro-esophageal junction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(5) CD004063. 20464727

5. Allum, W.H., Blazeby, J.M., Griffin, S.M., et al, Guidelines for the management of oesophageal and gastric cancer. Gut. 2011;60(11):1449–1472. 21705456

6. Jeurnink, S.M., van Eijck, C.H., Steyerberg, E.W., et al, Stent versus gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol 2007; 7:18. 17559659

7. Ly, J., O’Grady, G., Mittal, A., et al, A systematic review of methods to palliate malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(2):290–297. 19551436

8. Wagner, A.D., Unverzagt, S., Grothe, W., et al, Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(3) CD004064. 20238327

9. Bang, Y.J., Van Cutsem, E., Feyereislova, A., et al, Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687–697. 20728210

10. Bartels, H., Stein, H.J., Siewert, J.R., Preoperative risk analysis and postoperative mortality of oesophagectomy for resectable oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85(6):840–844. 9667720

11. Eloubeidi, M.A., Desmond, R., Arguedas, M.R., et al, Prognostic factors for the survival of patients with esophageal carcinoma in the U.S.: the importance of tumor length and lymph node status. Cancer. 2002;95(7):1434–1443. 12237911

12. The NHS cancer plan. London: Department of Health, 2000.

13. Executive NHS. Improving outcomes in upper-gastrointestinal cancers. The Manual, 2001.

14. Fleissig, A., Jenkins, V., Catt, S., et al, Multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: are they effective in the UK? Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(11):935–943. 17081919

15. Blazeby, J.M., Wilson, L., Metcalfe, C., et al, Analysis of clinical decision-making in multi-disciplinary cancer teams. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(3):457–460. 16322114

16. Strong, S., Blencowe, N.S., Fox, T., et al, The role of multi-disciplinary teams in decision making for patients with recurrent malignant disease. Palliat Med. 2012;26(7):954–958. 22562966

17. Rutten, L.J., Arora, N.K., Bakos, A.D., et al, Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980–2003). Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(3):250–261. 15893206

18. Thrumurthy, S.G., Morris, J.J., Mughal, M.M., et al, Discrete-choice preference comparison between patients and doctors for the surgical management of oesophagogastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2011;98(8):1124–1131. 21674471

19. Cancer reform strategy. Department of Health, 2007.

20. Blazeby, J.M., Farndon, J.R., Donovan, J., et al, A prospective longitudinal study examining the quality of life of patients with esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88(8):1781–1787. 10760752

21. Sreedharan, A., Harris, K., Crellin, A., et al, Interventions for dysphagia in oesophageal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4) CD005048. 19821338

22. Homs, M.Y., Steyerberg, E.W., Eijkenboom, W.M., et al, Single-dose brachytherapy versus metal stent placement for the palliation of dysphagia from oesophageal cancer: multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9444):1497–1504. 15500894

23. Riley, S.A., Attwood, S.E., Guidelines on the use of oesophageal dilatation in clinical practice. Gut. 2004;53(Suppl. 1):i1–i6. 14724139

24. Knyrim, K., Wagner, H.J., Bethge, N., et al, A controlled trial of an expansile metal stent for palliation of esophageal obstruction due to inoperable cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(18):1302–1307. 7692297

25. Siersema, P.D., Hop, W.C., Dees, J., et al, Coated self-expanding metal stents versus latex prostheses for esophagogastric cancer with special reference to prior radiation and chemotherapy: a controlled, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47(2):113–120. 9512274

26. Shenfine, J., McNamee, P., Steen, N., Bond, J., Griffin, S.M., A randomized controlled clinical trial of palliative therapies for patients with inoperable esophageal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(7):1674–1685. 19436289

27. Conio, M., Repici, A., Battaglia, G., et al, A randomized prospective comparison of self-expandable plastic stents and partially covered self-expandable metal stents in the palliation of malignant esophageal dysphagia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(12):2667–2677. 18042102

28. Power, C., Byrne, P.J., Lim, K., et al, Superiority of anti-reflux stent compared with conventional stents in the palliative management of patients with cancer of the lower esophagus and esophago-gastric junction: results of a randomized clinical trial. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20(6):466–470. 17958720

29. Dallal, H.J., Smith, G.D., Grieve, D.C., et al, A randomized trial of thermal ablative therapy versus expandable metal stents in the palliative treatment of patients with esophageal carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54(5):549–557. 11677469

30. Adam, A., Ellul, J., Watkinson, A.F., et al, Palliation of inoperable esophageal carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial of laser therapy and stent placement. Radiology. 1997;202(2):344–348. 9015054

31. Manner, H., May, A., Rabenstein, T., et al, Prospective evaluation of a new high-power argon plasma coagulation system (hp-APC) in therapeutic gastrointestinal endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(3):397–405. 17354121

32. Barr, H., Dix, A.J., Kendall, C., et al, Review article: the potential role for photodynamic therapy in the management of upper gastrointestinal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(3):311–321. 11207506

33. Lightdale, C.J., Heier, S.K., Marcon, N.E., et al, Photodynamic therapy with porfimer sodium versus thermal ablation therapy with Nd:YAG laser for palliation of esophageal cancer: a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42(6):507–512. 8674919

34. Heier, S.K., Rothman, K.A., Heier, L.M., et al, Photodynamic therapy for obstructing esophageal cancer: light dosimetry and randomized comparison with Nd:YAG laser therapy. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(1):63–72. 7541003

35. Jensen, D.M., Machicado, G., Randall, G., et al, Comparison of low-power YAG laser and BICAP tumor probe for palliation of esophageal cancer strictures. Gastroenterology. 1988;94(6):1263–1270. 2452115

36. Nwokolo, C.U., Payne-James, J.J., Silk, D.B., et al, Palliation of malignant dysphagia by ethanol induced tumour necrosis. Gut. 1994;35(3):299–303. 7512062

37. Payne-James, J.J., Spiller, R.C., Misiewicz, J.J., et al, Use of ethanol-induced tumor necrosis to palliate dysphagia in patients with esophagogastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36(1):43–46. 1690158

38. Chung, S.C., Leong, H.T., Choi, C.Y., et al, Palliation of malignant oesophageal obstruction by endoscopic alcohol injection. Endoscopy. 1994;26(3):275–277. 7521294

39. Earlam, R., Cunha-Melo, J.R., Oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: I. A critical review of surgery. Br J Surg. 1980;67(6):381–390. 6155968

40. Bergquist, H., Wenger, U., Johnsson, E., et al, Stent insertion or endoluminal brachytherapy as palliation of patients with advanced cancer of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Dis Esophagus. 2005;18(3):131–139. 16045572

41. Homs, M.Y., Essink-Bot, M.L., Borsboom, G.J., et al, Quality of life after palliative treatment for oesophageal carcinoma – a prospective comparison between stent placement and single dose brachytherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(12):1862–1871. 15288288

42. Polinder, S., Homs, M.Y., Siersema, P.D., et al, Cost study of metal stent placement vs single-dose brachytherapy in the palliative treatment of oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(11):2067–2072. 15150566

43. Ferry D. Phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of gefitinib versus placebo in oesophageal cancer progressing after chemotherapy, http://public.ukcrn.org.uk/search/StudyDetail.aspx?StudyID=1754; [accessed 5.03.12].

44. Yacoub, L., Goldman, H., Odze, R.D., Transforming growth factor-alpha, epidermal growth factor receptor, and MiB-1 expression in Barrett’s-associated neoplasia: correlation with prognosis. Mod Pathol. 1997;10(2):105–112. 9127315

45. Ferry, D. Phase II, trial of gefitinib (ZD1839) in advanced adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus incorporating biopsy before and after gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 2004; 22(Suppl. 14):4021.

46. Assersohn, L., Brown, G., Cunningham, D., et al, Phase II study of irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin in patients with primary refractory or relapsed advanced oesophageal and gastric carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(1):64–69. 14679122

47. Lordick, F., von Schilling, C., Bernhard, H., et al, Phase II trial of irinotecan plus docetaxel in cisplatin-pretreated relapsed or refractory oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(4):630–633. 12915869

48. Ferry, D.R., Anderson, M., Beddard, K., et al, A phase II study of gefitinib monotherapy in advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma: evidence of gene expression, cellular, and clinical response. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(19):5869–5875. 17908981

49. Cook, T.A., Dehn, T.C., Use of covered expandable metal stents in the treatment of oesophageal carcinoma and tracheo-oesophageal fistula. Br J Surg. 1996;83(10):1417–1418. 8944460

50. Ellul, J.P., Morgan, R., Gold, D., et al, Parallel self-expanding covered metal stents in the trachea and oesophagus for the palliation of complex high tracheo-oesophageal fistula. Br J Surg. 1996;83(12):1767–1768. 9038564

51. Griffin, S.M., Chung, S.C., van Hasselt, C.A., et al, Late swallowing and aspiration problems after esophagectomy for cancer: malignant infiltration of the recurrent laryngeal nerves and its management. Surgery. 1992;112(3):533–535. 1519169

52. Norman, G., Soares, M., Peura, P., et al, Capecitabine for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(Suppl. 2):11–17. 21047486

53. Okines, A., Chau, I., Cunningham, D., Capecitabine in gastric cancer. Drugs Today (Barc). 2008;44(8):629–640. 18846273

54. Chong, G., Cunningham, D., Can cisplatin and infused 5-fluorouracil be replaced by oxaliplatin and capecitabine in the treatment of advanced oesophagogastric cancer? The REAL 2 trial. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2005;17(2):79–80. 15830568

55. Kwok, S.P., Chung, S.C., Griffin, S.M., et al, Devine exclusion for unresectable carcinoma of the stomach. Br J Surg. 1991;78(6):684–685. 1712656

56. Heindorff, H., Wojdemann, M., Bisgaard, T., et al, Endoscopic palliation of inoperable cancer of the oesophagus or cardia by argon electrocoagulation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33(1):21–23. 9489903

57. Blazeby, J.M., Conroy, T., Bottomley, A., et al, Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-STO 22, to assess quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(15):2260–2268. 15454251

58. Lagergren, P., Fayers, P., Conroy, T., et al, Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OG25, to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the oesophagus, the oesophago-gastric junction and the stomach. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(14):2066–2073. 17702567

59. Blazeby, J.M., Conroy, T., Hammerlid, E., et al, Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(10):1384–1394. 12826041

60. Nicklin, J., Blazeby, J.M. Anorexia in patients dying from oesophageal and gastric cancers. Gastrointest Nurs. 2003; 1:35–39.

61. Irving, M., Oesophageal cancer and the role of the nurse specialist. Nurs Times 2002; 98:38–40. 12430403

62. Blomberg, J., Wenger, U., Lagergren, J., et al, Antireflux stent versus conventional stent in the palliation of distal esophageal cancer. A randomized, multicenter clinical trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45(2):208–216. 19968614

63. Verschuur, E.M., Repici, A., Kuipers, E.J., et al, New design esophageal stents for the palliation of dysphagia from esophageal or gastric cardia cancer: a randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(2):304–312. 17900325

64. Fu, J.H., Rong, T.H., Li, X.D., et al, Treatment of unresectable esophageal carcinoma by stenting with or without radiochemotherapy. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2004;26(2):109–111. 15059332

65. Sabharwal, T., Hamady, M.S., Chui, S., et al, A randomised prospective comparison of the Flamingo Wallstent and Ultraflex stent for palliation of dysphagia associated with lower third oesophageal carcinoma. Gut. 2003;52(7):922–926. 12801944

66. O’Donnell, C.A., Fullarton, G.M., Watt, E., et al, Randomized clinical trial comparing self-expanding metallic stents with plastic endoprostheses in the palliation of oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89(8):985–992. 12153622

67. Canto, M.I., Smith, C., McClelland, L., et al, Randomized trial of PDT vs. stent for palliation of malignant dysphagia: cost-effectiveness and quality of life. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55(5) Ab100. 11995711

68. Siersema, P.D., Hop, W.C., van Blankenstein, M., et al, A comparison of 3 types of covered metal stents for the palliation of patients with dysphagia caused by esophagogastric carcinoma: a prospective, randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54(2):145–153. 11474382

69. Vakil, N., Morris, A.I., Marcon, N., A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of covered expandable metal stents in the palliation of malignant esophageal obstruction at the gastroesophageal junction. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96:1791–1796. 11419831

70. Sargeant, I.R., Tobias, J.S., Blackman, G., et al, Radiotherapy enhances laser palliation of malignant dysphagia: a randomised study. Gut. 1997;40(3):362–369. 9135526

71. Higgins, J.P., Altman, D.G., Gotzsche, P.C., et al, The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J 2011; 343:d5928. 22008217