Chapter 10 Palliative medicine and symptom control

Introduction and general aspects

Palliative care is the active total care of patients who have advanced, progressive life-shortening disease. It is now recognized that palliative care should be based on needs not diagnosis: it is needed in many non-malignant diseases as well as in cancer (Box 10.1).

![]() Box 10.1

Box 10.1

Key components of a modern palliative care service

Management should be based on needs not diagnosis: the symptom burden of non-malignant disease often equals that of cancer

Management should be based on needs not diagnosis: the symptom burden of non-malignant disease often equals that of cancer

Care should be independent of the patients’ location and should help patients to remain at home if possible, avoiding unwanted admissions to hospital

Care should be independent of the patients’ location and should help patients to remain at home if possible, avoiding unwanted admissions to hospital

Rehabilitation for people with advanced disease

Rehabilitation for people with advanced disease

Bereavement care for people with pathological grief problems

Bereavement care for people with pathological grief problems

Telephone advice for other clinicians; disseminating palliative care knowledge

Telephone advice for other clinicians; disseminating palliative care knowledge

Teaching for clinicians, from undergraduate level to postgraduate life-long learning

Teaching for clinicians, from undergraduate level to postgraduate life-long learning

Importance of early assessment

If palliative care is seen only as relevant for the end-of-life phase, patients who have non-malignant disease are denied expert help for complex symptoms. Timely management of physical and psychosocial issues earlier in the course of disease prevents intractable problems later (Box 10.2).

![]() Box 10.2

Box 10.2

Problems arising when specialist palliative care (SPC) is delayed until the end-of-life

There is insufficient time to achieve good symptom control by combining non-pharmacological and pharmacological components

There is insufficient time to achieve good symptom control by combining non-pharmacological and pharmacological components

SPC services are deemed less acceptable by patient and family, being associated with ‘dying’ or ‘giving up’ or ‘giving in’ to illness

SPC services are deemed less acceptable by patient and family, being associated with ‘dying’ or ‘giving up’ or ‘giving in’ to illness

Psychological distress and physical symptoms become intractable and contribute to complex grief

Psychological distress and physical symptoms become intractable and contribute to complex grief

It becomes too late to adopt rehabilitative approach or teach/use non-pharmacological interventions that need a degree of training and patient motivation (e.g. cognitive behavioural approaches, mindfulness meditation, attendance at day therapy)

It becomes too late to adopt rehabilitative approach or teach/use non-pharmacological interventions that need a degree of training and patient motivation (e.g. cognitive behavioural approaches, mindfulness meditation, attendance at day therapy)

Symptom control

This section outlines the medical aspects of symptom control. Good palliative care integrates these with appropriate non-pharmacological approaches, including anxiety management and rehabilitation (see p. 489).

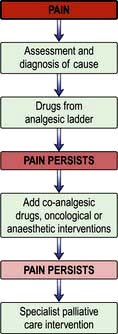

Pain

Pain is a feared symptom in cancer and at least two-thirds of people with cancer suffer significant pain. Pain has a number of causes, and not all pains respond equally well to opioid analgesics (Fig. 10.1). The pain is either related directly to the tumour (e.g. pressure on a nerve) or indirectly, for example due to weight loss or pressure sores. It may result from a co-morbidity such as arthritis. Emotional and spiritual distress may be expressed as physical pain (termed ‘opioid irrelevant pain’) or will exacerbate physical pain.

The term ‘total pain’ encompasses a variety of influences that contribute to pain:

Biological: the cancer itself, cancer therapy (drugs, surgery, radiotherapy)

Biological: the cancer itself, cancer therapy (drugs, surgery, radiotherapy)

Social: family distress, loss of independence, financial problems from job loss

Social: family distress, loss of independence, financial problems from job loss

Psychological: fear of dying, pain, or being in hospital; anger at dying or at the process of diagnosis and delays; depression from all of above

Psychological: fear of dying, pain, or being in hospital; anger at dying or at the process of diagnosis and delays; depression from all of above

Spiritual: fear of death, questions about life’s meaning, guilt.

Spiritual: fear of death, questions about life’s meaning, guilt.

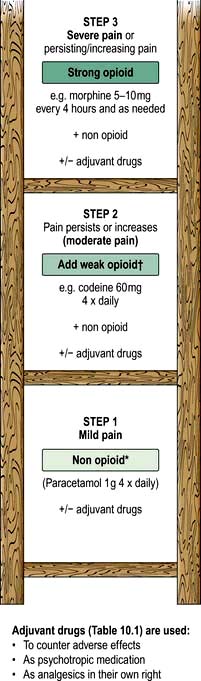

The WHO analgesic ladder

Most cancer pain can be managed with oral or commonly used transdermal preparations. The World Health Organization (WHO) cancer pain relief ladder guides the choice of analgesic according to pain severity (Fig. 10.2, Table 10.1).

Figure 10.2 WHO analgesic ladder for cancer and other chronic pain. Step 2 can be omitted, going to morphine immediately. Adjuvant drugs are listed in Table 10.1. *Opioids include all drugs with an action similar to morphine, i.e. binding to endogenous opioid receptors. †Continue NSAID/paracetamol regularly when opioid started.

| Drugs | Indication |

|---|---|

|

NSAIDs, e.g. diclofenac |

Bone pain, inflammatory pain |

|

Anticonvulsants, e.g. gabapentin (600–2400 mg daily) or pregabalin (150 mg at start increasing up to 600 mg daily) |

Neuropathic pain |

|

Tricyclic antidepressants, e.g. amitriptyline (10–75 mg daily) |

Neuropathic pain |

|

Bisphosphonates, e.g. disodium pamidronate |

Metastatic bone disease |

|

Dexamethasone |

Neuropathic pain, inflammatory pain (e.g. liver capsule pain), headache from cerebral oedema due to brain tumour |

If regular use of optimum dosing (e.g. paracetamol 1 g × 4 daily for step 1) does not control the pain, then an analgesic from the next step of the ladder is prescribed. As pain is due to different physical aetiologies, an adjuvant analgesic may be needed in addition or instead, such as the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline for neuropathic pain (Table 10.1).

Strong opioid drugs

Side-effects

The most common side-effects are:

Nausea and vomiting: this can usually be managed or prevented with antiemetics (such as metoclopramide). Some antiemetics can be combined with an opioid, e.g. haloperidol or metoclopramide; always check compatibility data.

Nausea and vomiting: this can usually be managed or prevented with antiemetics (such as metoclopramide). Some antiemetics can be combined with an opioid, e.g. haloperidol or metoclopramide; always check compatibility data.

Constipation is common and should be anticipated with administration of a combination of stool softener (e.g. macrogols) and stimulants either separately or in one preparation Methyl naltrexone is a peripherally acting opioid receptor antagonist which is used if response to other laxatives is poor.

Constipation is common and should be anticipated with administration of a combination of stool softener (e.g. macrogols) and stimulants either separately or in one preparation Methyl naltrexone is a peripherally acting opioid receptor antagonist which is used if response to other laxatives is poor.

If side-effects are intractable, a change of opioid is often helpful.

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Respiratory symptoms

Breathlessness

Breathlessness remains one of the most distressing and common symptoms in palliative care; causing the patient serious discomfort, it is highly distressing for carers to witness. Full assessment and active treatment of all reversible conditions, such as drainage of pleural effusions, or optimization of treatment of heart failure or chronic pulmonary disease is mandatory. In advanced cancer, breathlessness is often multifactorial in origin and many of the contributory factors are irreversible (e.g. cachexia), so a ‘complex intervention’ combining a number of different treatment strategies has the greatest impact. Aspects of breathlessness management are summarized in Box 10.3.

![]() Box 10.3

Box 10.3

Key points for successful management of breathlessness

Start treatment early: patients who are likely to develop breathlessness should learn non-pharmacological approaches early in the disease course, before breathlessness has become severe.

Start treatment early: patients who are likely to develop breathlessness should learn non-pharmacological approaches early in the disease course, before breathlessness has become severe.

Involve the carer in the treatment strategy: watching breathlessness episodes and being unable to help is a terrifying experience (and promotes the panic–anxiety cycle); if patients and carers develop a joint ritual for crises, chronic anxiety can be reduced.

Involve the carer in the treatment strategy: watching breathlessness episodes and being unable to help is a terrifying experience (and promotes the panic–anxiety cycle); if patients and carers develop a joint ritual for crises, chronic anxiety can be reduced.

Ensure management is rehabilitative (see p. 489): this increases physical fitness, hope, self-efficacy, and may enable patient and carer to achieve goals that once seemed impossible.

Ensure management is rehabilitative (see p. 489): this increases physical fitness, hope, self-efficacy, and may enable patient and carer to achieve goals that once seemed impossible.

Integrate psychological, physical and social interventions, as with all palliative care.

Integrate psychological, physical and social interventions, as with all palliative care.

Breathlessness with panic and anxiety

Using a hand-held fan to alleviate breathlessness. For more on interventions for breathlessness, see http://www.cuh.org.uk/breathlessness.

Non-pharmacological approaches such as using a hand-held fan, pacing, prioritizing activities to avoid over-exertion, breathing training and anxiety management are helpful (Table 10.2). There is no evidence to suggest that oxygen therapy reduces the sensation of breathlessness in advanced disease and the hand-held fan should be used before oxygen for this purpose. Opioids, used orally or parenterally, can palliate breathlessness. If panic/anxiety is significant, a quick-acting benzodiazepine such as lorazepam (used sublingually for rapid absorption) may be useful.

Table 10.2 Key non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness

| Intervention | Putative mechanism of action | Most useful |

|---|---|---|

|

Hand-held fan |

Cooling area served by 2nd and 3rd branches of trigeminal nerve |

Reducing length of episodes of SOB on exertion or at rest |

|

Reduces temperature of air flowing over nasal receptors, altering signal to brainstem respiratory complex and so changing respiratory pattern |

Gives patient and carer confidence to have an intervention they can use |

|

|

Exercise |

Stops spiral of disability developing |

Patients who are still quite mobile. |

|

Changes muscle structure: less lactic acid produced |

In patients who have not developed onset of SOB, reduce/defer symptoms by reducing deconditioning |

|

|

Anxiety reduction, e.g. CBT (needs skilled clinician to administer) or simple relaxation therapy |

Works on central perception of breathlessness reducing impact |

People with higher levels of anxiety at baseline (i.e. when first seen) |

|

Interrupting panic/anxiety cycle |

Patients willing to persevere with learning a new skill |

|

|

Carer support |

Reduces carer anxiety and distress which is part of ‘total’ anxiety–panic cycle |

Where carer is isolated, under extra pressures (e.g. looking after elderly parent, going through divorce) |

|

Breathing retraining |

Improve mechanical effectiveness respiratory system |

Chronic advanced respiratory disease and those with anxiety-related breathlessness |

|

Pacing (finding a balance between activity and rest to achieve aims) and prioritizing (deciding which daily activities are most necessary and focusing energy use on them) |

Avoids over-exertion which can lead to exhaustion, inactivity and subsequent deconditioning |

Patients who are able and willing to modify daily routines |

|

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation |

Increases muscle bulk, simulating effect of exercise |

Patients who live alone |

|

Those unable to get out to attend rehabilitation group |

||

|

People with a short prognosis |

||

|

People with co-morbidities that prevent exercise |

CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; SOB, short of breath (breathlessness).

Other physical symptoms

Fatigue

Non-pharmacological: relaxation, sleep hygiene, resting ‘pro-actively’ rather than collapsing when exhausted, and planning, pacing and prioritizing daily activities

Non-pharmacological: relaxation, sleep hygiene, resting ‘pro-actively’ rather than collapsing when exhausted, and planning, pacing and prioritizing daily activities

Pharmacological: low dose methylphenidate or modafinil (central nervous system stimulants), done in conjunction with the specialist palliative care team, may help.

Pharmacological: low dose methylphenidate or modafinil (central nervous system stimulants), done in conjunction with the specialist palliative care team, may help.

Loss of function, disability and rehabilitation

contribute to patients’ quality of life by providing strategies for managing declining physical function and fatigue, and by offering resources that might make life easier for patients and carers (e.g. equipment or a wheelchair)

contribute to patients’ quality of life by providing strategies for managing declining physical function and fatigue, and by offering resources that might make life easier for patients and carers (e.g. equipment or a wheelchair)

support patients’ adaptation to disability, helping them to increase social participation and find fulfilment in everyday living

support patients’ adaptation to disability, helping them to increase social participation and find fulfilment in everyday living

Extending palliative care to people with non-malignant disease

The principles of palliative care can be applied throughout medical practice so that all patients, irrespective of care setting (home, hospital or hospice) receive appropriate care from the staff looking after them and have access to SPC services for complex issues. Some principles are outlined in Box 10.4. Patients who have chronic non-malignant disease such as organ failures (heart, lung and kidney), degenerative neurological disease and HIV infection:

have a similar or greater symptom burden than people with cancer

have a similar or greater symptom burden than people with cancer

may live longer with these difficulties

may live longer with these difficulties

benefit from a palliative care approach with access to SPC for complex problems.

benefit from a palliative care approach with access to SPC for complex problems.

![]() Box 10.4

Box 10.4

Key points in palliative care

Patients should always be involved in decisions about their care.

Patients should always be involved in decisions about their care.

Quality of life is increased when treatment goals are clearly understood by everyone, including patient and carer.

Quality of life is increased when treatment goals are clearly understood by everyone, including patient and carer.

The multidisciplinary team can provide a high standard of care but there must be realism and honesty about what can be achieved.

The multidisciplinary team can provide a high standard of care but there must be realism and honesty about what can be achieved.

Hospitalization is sometimes necessary but end-of-life care is often delivered in hospices or the home.

Hospitalization is sometimes necessary but end-of-life care is often delivered in hospices or the home.

Care at home should be encouraged for as long as possible, even if the patient’s preferred place of death is elsewhere.

Care at home should be encouraged for as long as possible, even if the patient’s preferred place of death is elsewhere.

Discussions about end-of-life care planning are best held outside times of crisis, when the patient feels as well as possible, with clinicians with whom they have a good relationship. The results of these discussions must be recorded and made known to everyone involved in the patient’s care.

Discussions about end-of-life care planning are best held outside times of crisis, when the patient feels as well as possible, with clinicians with whom they have a good relationship. The results of these discussions must be recorded and made known to everyone involved in the patient’s care.

Patients who have non-malignant disease may have very close relationships with their usual team, and an integrated approach is essential to allow optimization of disease-directed medication as well as palliation. People with non-malignant disease may live for years with a difficult illness and so their palliative care needs to differ in some respects from those of cancer patients (Table 10.3). However, symptom management is largely transferable, with some exceptions and extra complexities as outlined below.

Table 10.3 Differences between palliative care for people with malignant and non-malignant diseases

| Cancer | Non-malignant disease |

|---|---|

|

Standard treatment regimens even in advanced disease |

Advanced disease often needs bespoke pharmacological interventions, which may interact with palliative drugs. Close teamwork is essential to avoid adversely affecting outcomes, e.g. in use of opioids and many other drugs |

|

Relatively new diagnosis (weeks to months) |

Usually many years of illness with loss of social networks, employment and practical support |

|

Sudden death is rare (although it can happen, e.g. pulmonary embolus, neutropenic sepsis) |

Sudden death is relatively frequent as a result of cardiovascular/diabetic complications (e.g. in chronic kidney disease) |

|

Cancer and associated problems are the main morbidities |

Co-morbidities due to disease or treatment often cause most problems and shape end-of-life care |

|

Prognosis is usually predictable |

Prognosis difficult to determine: many ‘near death experiences’, admissions and recoveries occur |

|

Support from SPC services is often started early in the disease course |

Main support may be from a medical unit, e.g. dialysis unit |

|

Standard hospice services (e.g. day therapy) often suit treatment patterns well |

Standard hospice service may not be offered (clinician ignorance) or may not be feasible (e.g. for dialysis patient attending hospital 3 days a week) |

Heart failure

There are special considerations with respect to cardiac medication in advanced disease:

Drugs that are commonly used in palliative care but usually contraindicated in heart failure, such as amitriptyline and NSAIDs, may be appropriate at the very end-of-life.

Drugs that are commonly used in palliative care but usually contraindicated in heart failure, such as amitriptyline and NSAIDs, may be appropriate at the very end-of-life.

Sudden death is more common than in patients who have malignancy and a patient may have an implanted defibrillator in place. If present, these devices should be re-programmed to pacemaker mode in advanced disease because they have not been shown to improve survival in severe heart failure and it will be distressing for patient, carer and staff if they discharge as the patient is dying.

Sudden death is more common than in patients who have malignancy and a patient may have an implanted defibrillator in place. If present, these devices should be re-programmed to pacemaker mode in advanced disease because they have not been shown to improve survival in severe heart failure and it will be distressing for patient, carer and staff if they discharge as the patient is dying.

Peripheral oedema can become a major problem and more resistant to diuretic therapy, therefore careful balancing of medication regimens is required. Ultimately symptom relief is prioritized over renal function.

Peripheral oedema can become a major problem and more resistant to diuretic therapy, therefore careful balancing of medication regimens is required. Ultimately symptom relief is prioritized over renal function.

Medications should be rationalized to reduce polypharmacy, e.g. ceasing drugs prescribed to reduce long-term secondary risk (e.g. statins) and continuing drugs that help symptom control (including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, which benefit symptoms as well as survival). Beta blockers may have to be stopped if the patient can no longer maintain non-symptomatic hypotension.

Medications should be rationalized to reduce polypharmacy, e.g. ceasing drugs prescribed to reduce long-term secondary risk (e.g. statins) and continuing drugs that help symptom control (including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, which benefit symptoms as well as survival). Beta blockers may have to be stopped if the patient can no longer maintain non-symptomatic hypotension.

Chronic respiratory disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Because of the risk of dependency, falls and memory problems, non-pharmacological approaches to anxiety are more appropriate than benzodiazepines (Table 10.2). Short-acting benzodiazepines should be reserved for severe panic episodes.

Other chronic respiratory diseases

Other chronic respiratory illnesses that often require palliative care include:

Diffuse parenchymal lung disorders (interstitial lung disease) (ILD): this has a trajectory similar to cancer with rapidly developing breathlessness and cough. The breathlessness of ILD is particularly frightening but may respond well to opioids: early access to hospice services is particularly relevant to help with symptom control and anxiety.

Diffuse parenchymal lung disorders (interstitial lung disease) (ILD): this has a trajectory similar to cancer with rapidly developing breathlessness and cough. The breathlessness of ILD is particularly frightening but may respond well to opioids: early access to hospice services is particularly relevant to help with symptom control and anxiety.

Cystic fibrosis: patients are teenagers or young adults who usually have known their respiratory team all their lives. An integrated team involving SPC clinicians ensures good symptom control and provides useful support when difficult decisions have to be made about treatments (e.g. lung transplant), as well as offering psychosocial care to the family.

Cystic fibrosis: patients are teenagers or young adults who usually have known their respiratory team all their lives. An integrated team involving SPC clinicians ensures good symptom control and provides useful support when difficult decisions have to be made about treatments (e.g. lung transplant), as well as offering psychosocial care to the family.

Primary pulmonary hypertension: patients are often young and treated far from home in specialist centres. They require symptom control in close consultation with the medical team, and it is essential that any dependent children receive the care they need.

Primary pulmonary hypertension: patients are often young and treated far from home in specialist centres. They require symptom control in close consultation with the medical team, and it is essential that any dependent children receive the care they need.

Renal disease

Patients who are not on dialysis

Medication that accelerates loss of renal function may markedly reduce survival in those patients who are able to live months or years with very little remaining renal function.

Medication that accelerates loss of renal function may markedly reduce survival in those patients who are able to live months or years with very little remaining renal function.

The renal impact of both dose and drug choice must be taken into account, e.g. morphine and diamorphine metabolites accumulate in end-stage renal dysfunction, thus strong opioids such as alfentanil or fentanyl should be used instead.

The renal impact of both dose and drug choice must be taken into account, e.g. morphine and diamorphine metabolites accumulate in end-stage renal dysfunction, thus strong opioids such as alfentanil or fentanyl should be used instead.

Close liaison with the medical team is essential for drug prescribing.

Neurological disease

Difficulties in swallowing (e.g. in motor neurone disease)

Difficulties in swallowing (e.g. in motor neurone disease)

Loss of mental capacity – the ability to understand, weigh up, come to a decision and communicate that decision.

Loss of mental capacity – the ability to understand, weigh up, come to a decision and communicate that decision.

Motor neurone disease

Motor neurone disease is usually rapidly progressive, often requiring hospice support. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (p. 222) feeding may be required. In addition, if ventilatory failure develops, nocturnal non-invasive ventilation may be offered. Patients and their carers need to understand:

Dementia

Dementia-related palliative care needs arise in the context of:

Care of the dying

FURTHER READING

Department of Health. End of Life Care Strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health; 2008:16 July.

General Medical Council. Treatment and Care Towards the End of Life: good practice in decision making. London: General Medical Council; 2010.

Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute Liverpool (MCPCIL) in collaboration with the Clinical Standards Department of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP). National Care of the Dying Audit – Hospitals (NCDAH) Round 2, 2008–9. Supported by the Marie Curie Cancer Care and the Department of Health End of Life Care Programme; 2009.

Do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) orders

• The resuscitation status of every patient should be discussed by senior doctors at the time of admission and the decision documented in the notes.

• Many hospitals have specific DNAR forms. Deciding a person’s resuscitation status is a careful balance of risk versus benfit. The patient’s co-morbidities and pre-morbid quality of life should be taken into account.

• Involve the patient and family in this discussion, and explain the medical reasoning behind the decision. If the patient requests that CPR is not performed in the event of cardio-pulmonary arrest, those wishes should be respected.

An end-of-life tool: the Liverpool Care Pathway

The Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) is a four-stage end-of-life tool designed to transfer the standard of hospice care of the dying into the hospital (Box 10.5). Now adapted for any setting, it is the most commonly used pathway for care of the dying in the UK and in several other countries. There have been no trials comparing effectiveness of any end-of-life care pathways against usual care without a pathway, but serial UK national hospital audits have been able to assess and monitor the level of care documented against the standards set in the LCP.

BNF. Guidance on prescribing: prescribing in palliative care. British National Formulary. London: BMJ Group and RPS Publishing http://bnf.org/bnf/bnf/current

Goldstein NE, Fischberg D. Update in palliative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:135–140.

Twycross R, Wilcock A. Palliative Care Formulary, 4th edn. Nottingham: Palliativebooks.com; 2011.