chapter 39 Palliative medicine

GOALS OF CARE

Many important decisions may need to be made by a person confronted with a life-limiting illness. For an excellent and practical guideline on how to approach this, the reader is referred to Clayton & Hancock, ‘Clinical practice guidelines for communicating prognosis and end-of-life issues with adults in the advanced stages of a terminal illness, and their caregivers’, published as a supplement in the Medical Journal of Australia.1

CARING FOR THE WHOLE PERSON

A deep-seated fear of dying, for example, or longstanding and unresolved guilt can have an enormous impact on how a patient deals with physical pain. It is not uncommon for deeper emotional and existential issues to influence and magnify such symptoms. If physical treatments only are administered (e.g. prescribing escalating doses of pain killers) but the underlying emotional and existential issues are not acknowledged or dealt with, then the problem of pain will likely be unsolvable, whereas if these deeper issues are dealt with well, the pain will often be far more manageable.

Most patients confronting life-threatening illnesses wish to speak to their medical team about spiritual and religious issues (see Ch 12, Spirituality). Whether the doctor provides such counselling or helps to link the patient with counsellors, pastoral care and allied healthcare professionals, one way or another this aspect of care needs to take place and not be ignored among the more obvious and apparently more pressing physical needs.

THE ROLE OF COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES

The frequency of complementary therapy use by cancer patients may be as high as 83%2 (see Ch 24, Cancer). This includes herbal medicines, music therapy and physical therapies such as acupuncture, among others. Patients use these therapies to improve symptoms, in the hope of curing cancer or increasing survival, and as a response to pressure from family or friends.3 It is certainly reasonable to encourage the use of those therapies that are proving helpful to the patient without causing undue hardship or interfering with conventional treatment. Some incur a considerable cost with little or no benefit, and occasionally there may be a risk of the therapy interfering with conventional medical care or causing harm to the patient. For example, many herbs can interact with drugs such as warfarin. The GP has an important role in discussing the use of such therapies with the patient.

PAIN

Pain is a complex experience involving specific neural pathways that convey nociceptive information to consciousness. Neuronal systems also exist that modify pain—for example, descending inhibitory pathways in the central nervous system. This chapter focuses mainly on cancer pain, but many of the principles can be applied to non-malignant pain in patients with advanced or near end-stage disease. Chronic pain, while sharing some features, requires important differences in approach and is not discussed here (see Ch 38, Pain management).

Pain is common is cancer and more so in advanced malignancy, with 70–90% of patients reporting pain.4 It is also common in the elderly (28–86% of nursing home residents5) and in those with other chronic disease (e.g. 40% of patients with Parkinson’s disease). As such, competent assessment and management of pain is a crucial skill for GPs.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

HISTORY AND EXAMINATION

Careful history and examination can often assist in determining the likely pathophysiology and aetiology of a patient’s pain. The history will focus on the qualities, temporal features and other descriptive features of the pain. Details such as location, duration, onset, offset, relieving and exacerbating features should be elicited, along with a description of pain quality. It is clearly important to enquire about other symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, history of a recent fall, previous treatments and so on.

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Non-pharmacological

Pharmacological

The choice of agent will depend on:

Generally, analgesia for cancer pain should be given:

Simple analgesics

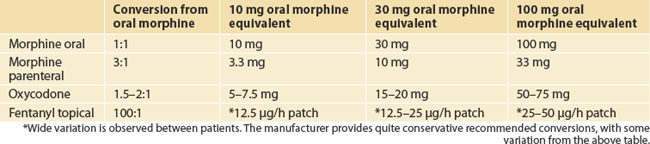

Opioids

Adjuvant agents

PITFALLS

CONSTIPATION

HISTORY AND EXAMINATION

History should include specific details of the symptoms, including:

Other important information includes:

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Many patients will be aware of particular foods or strategies that are of benefit. Some examples are licorice, beer or dried fruit. Natural therapies with demonstrated benefit include cascara, senna and pureed rhubarb.12

Pharmacological

Most patients, particularly those requiring opioid analgesia, will need laxatives to ease constipation. These should be taken regularly rather than ‘as needed’, with the dose titrated to maintain comfort. Laxatives can be classed as softening agents or peristaltic agents (Box 39.2), and the initial choice of drug can be guided by the predominant symptom—that is, hard faeces or faeces that are soft but difficult to pass. Bowel obstruction should be excluded prior to commencing laxatives, particularly the stimulants.

More recently available in Australia is methylnaltrexone bromide. This is a selective μ-opioid receptor antagonist, specifically targeted at the treatment of opioid-induced constipation. Because it has very limited capacity to cross the blood–brain barrier it is able to reverse the constipating effect of opioids in the bowel, without compromising analgesia. It is given as a subcutaneous injection and usually has a rapid onset of action, usually within 4 hours.13

NAUSEA/VOMITING

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND AETIOLOGY

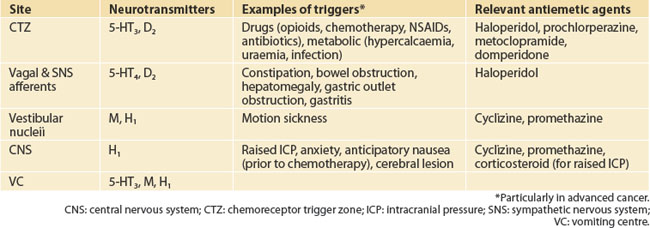

Vomiting is controlled by the vomiting centre (VC), a number of adjacent, coordinated sites located in the lateral reticular formation of the medulla. The physiology of nausea is not as well understood but it may arise when stimuli excite the VC without sufficient amplification to trigger the vomiting cascade. A variety of neurotransmitters are involved at various sites, and knowledge of these can be exploited in order to target therapy (Table 39.2).

Inputs to the VC include the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), located in the floor of the fourth ventricle. An effective absence of the blood–brain barrier allows chemosensitive nerve cell endings direct contact with cerebrospinal fluid, which is in chemical equilibrium with blood. The relevant neurotransmitters are serotonin (5-HT3) and dopamine (D2). Vagal and sympathetic afferents are activated by gastric irritation, gastric distension, intestinal obstruction, constipation, liver disease and so on. Important neurotransmitters are 5-HT4 and D2. Vestibular nuclei activated by labyrinthitis, motion sickness and so on act via muscarinic (M) and histaminergic (H1) neurotransmitters. Further input comes from the CNS (H1) and is important in nausea induced by anxiety, fear, raised intracranial pressure, cerebral lesion, meningitis and the senses (taste, smell). Important neurotransmitters of the VC are H1, M and 5-HT3.

INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT

Pharmacological

Principles

PITFALLS

ANOREXIA/CACHEXIA

A cancer anorexia/cachexia syndrome has been described where:

CLINICAL

A careful history and examination is required, aiming to detect the presence of treatable factors. Specific enquiry should be made about the presence of nausea, constipation, mouth pain, dysphagia and so on. Features indicative of depression or the presence of infection should also be sought (e.g. dysuria, productive cough, rigors) and a list of medications obtained.

INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT

Pharmacological measures

Supplemental Feeding

OTHER SYMPTOMS AND CARE IN THE LAST DAYS OF LIFE

LAST DAYS OF LIFE

CareSearch, palliative care knowledge network—an online resource of palliative care information and evidence. http://www.caresearch.com.au.

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre. http://www.mskcc.org.

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre, Integrative Medicine Service. http://www.mskcc.org/mskcc/html/1979.cfm.

Palliative Care Australia—includes fact sheets, reports and a resource directory. http://www.pallcare.org.au.

Therapeutic Guidelines, Palliative Care—concise, practical information on all aspects of palliative care

Twycross R. Introducing palliative care, 2nd edn. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1997. —a concise but comprehensive introduction to all aspects of palliative care, including communication, ethics, drug profiles and more

Woodruff R. Palliative medicine: evidence-based symptomatic and supportive care for patients with advanced cancer, 4th edn. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press, 2004. —written by an Australian oncologist/palliative care physician

1 Clayton JM, Hancock KM, Tattersall MHN, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for communicating prognosis and end-of-life issues with adults in the advanced stages of a terminal illness, and their caregivers. Med J Aust. 2007;186(12):S18.

2 Zappa SB, Cassileth BR. Complementary approaches to palliative oncological care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18(1):22-26.

3 Oneschuk D, Hanson J, Bruera E. Complementary therapy use: a survey of community- and hospital-based patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2000;14(5):432-434.

4 Foley KM. Acute and chronic cancer pain syndromes. In: Doyle D, Hanks G, Cherny N, et al, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:298-316.

5 Pain in residential aged care facilities. Management strategies. Sydney: Australian Pain Society, 2005.

6 Bowsher D. The effects of pre-emptive treatment of postherpetic neuralgia with amitriptyline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13(6):327-331.

7 Bardia A, Barton DL, Prokop LJ, et al. Efficacy of complementary and alternative medicine therapies in relieving cancer pain: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(34):5457-5464.

8 Deng G, Cassileth BR. Integrative oncology: complementary therapies for pain, anxiety, and mood disturbance. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:109-116.

9 Cassileth BR, Vickers AJ. Massage therapy for symptom control: outcome study at a major cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(3):244-249.

10 Fellowes D, Barnes K, Wilkinson S. Aromatherapy and massage for symptom relief in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:CD002287.

11 Beck SL. The therapeutic use of music for cancer-related pain. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:1327-1337.

12 Cassileth BR. Complementary and alternative cancer medicine. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(11 Suppl):44-52.

13 Portenoy RK, Thomas J, Moehl Boatwright ML, et al. Subcutaneous methylnaltrexone for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in patients with advanced illness: a double-blind, randomized, parallel group, dose-ranging study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(5):458-468.

14 Ezzo JM, Richardson MA, Vickers A, et al. Acupuncture-points stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD002285.

15 Berenstein EG, Ortiz Z. Megestrol acetate for the treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD004310.

16 Dewey A, Baughan C, Dean T, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, an omega-3 fatty acid from fish oils) for the treatment of cancer cachexia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD004597.