Palliative care in haematological malignancy

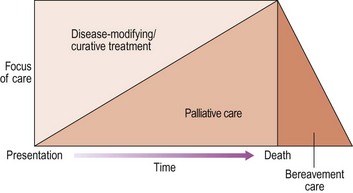

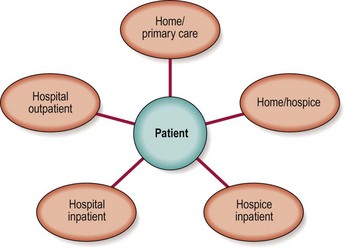

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual’. As the modern specialty of palliative medicine was born in the hospice movement, there has been a tendency to regard it as an end-of-life intervention, an option only when disease-modifying cancer treatments have been exhausted. It is more correctly viewed as being entirely complementary to ongoing anti-tumour treatment – for instance, a patient with myeloma presenting with refractory bone pain is likely to benefit from expert symptom control early in their illness (Fig 47.1). Good palliative care requires a multidisciplinary team approach with staff expert in communication and control of symptoms and with the organisational skills to coordinate care. Patients commonly derive palliative care input from diverse sources (Fig 47.2). There is not space here to comprehensively review all aspects of palliative care but a number of applications with particular relevance to patients with haematological malignancy will be discussed.

Palliative chemotherapy and radiotherapy

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy are primarily employed as disease-modifying treatments but they may also be used in a palliative context to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life. Any side-effects of such treatment must be carefully weighed against the likely symptom control. Chemotherapy may thus be used to limit the degree of troublesome lymphadenopathy in advanced lymphoma or to reduce the systemic upset from a high malignant cell burden in end-stage leukaemia. Similarly, attenuated radiotherapy can give local relief from tumour infiltration in lymphoma and can reduce pain from myeloma bone lesions (Fig 47.3). Surgical interventions are used more sparingly but lymphomatous pleural effusions can be drained and the severe pain of myelomatous spinal disease can be ameliorated by the operation of vertebroplasty where the vertebrae are reinforced with a cement-like substance.

Control of non-pain symptoms

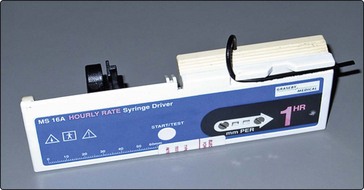

Care at of the end of life. In patients with advanced disease and refractory symptoms in the final days of life, sedation may be used in the form of continuous drug infusions via portable syringe drivers (Fig 47.4). Strict criteria must be used for patient selection and fully informed consent must be obtained from the patient (where possible) and their family. Such measures should only be resorted to after consultation with the palliative care team.