CHAPTER 126 Palliative Care for Patients with Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Disease

WHAT IS PALLIATIVE MEDICINE?

Palliative care is interdisciplinary care that aims to improve the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness through preventing and relieving suffering by identifying, assessing, and treating pain and other problems, including physical, psychosocial, and spiritual ones.1 Although palliative care often is provided to patients with life-threatening illness that is not responsive to curative treatment,2 it can and should be offered concurrently with all other appropriate medical therapies including cure-oriented treatments.

Palliative medicine recognizes that dying is a normal life cycle event and seeks neither to unnecessarily hasten nor postpone death, but rather to focus care on patient-defined goals as death nears.2 Most patients want to die with comfort and dignity and are able to articulate some or all of the following goals3:

Quality care near the end of life for complex physical and psychological problems cannot be provided by a single clinician. Care ideally is provided by an interdisciplinary team that includes physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, and bereavement counselors. The interdisciplinary palliative care team works in concert with, and does not replace, the primary medical team. Thus, the ultimate goal of palliative care is to prevent and relieve suffering and to optimize quality of life for patients and their families, regardless of the stage of the disease or the need for curative or palliative therapies. The American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine provides a list of palliative medicine and hospice physicians on their website (www.aahpm.org).

HOSPICE VERSUS PALLIATIVE CARE

Palliative medicine and hospice care share the same philosophy of care. Unlike palliative medicine, however, hospice care in the United States is also a financial reimbursement system for the terminally ill patients, largely defined by the Medicare Hospice Benefit (MHB). As such, hospice care has defined regulations and admission criteria. Under the MHB, patients are eligible for a specific set of services if the physician certifies that the patient has six months or less to live, if the disease follows its usual course, and if the goal of treatment is palliative rather than curative.4 MHB does not require patients to relinquish heroic life-prolonging measures, future hospitalizations, or participation in research. Prognosis is based on the attending physician’s clinical judgment regarding the normal course of the person’s illness; if the patient lives beyond the expected six months, the hospice care may be continued by recertifying the patient under MHB. Although hospice care can be provided in special residential facilities or in long-term care facilities, currently most hospice care in the United States is provided in the patient’s home.

In contrast to hospice care, there are no specific eligibility criteria for palliative care because there is no specially defined reimbursement mechanism. The palliative care movement in the United States has developed largely in acute care hospitals and, more recently, in long-term care facilities. Therefore, all hospice care is palliative care, but not all palliative care is hospice care (Table 126-1). To truly provide seamless care of patients who are dying, communities need both palliative care and hospice services. There are 65 Hospice and Palliative Medicine fellowship programs in the country, and board certification is available through the American Board of Medical Specialties for the subspecialty of hospice and palliative medicine.5

Table 126-1 What Is Palliative Care?

Adapted from World Health Organization, 2008.

EXPLORING THE GOALS OF CARE

Exploring patient-defined goals of care is the first step in determining the most appropriate therapeutic interventions for a specific disease or symptom. An organized approach to goal setting can help the clinician and patient achieve clearly articulated goals. Goal setting is best accomplished through meeting with the patient and family or surrogate decision-maker (Table 126-2). Before a goal-setting meeting, the clinician should review the disease course, response to prior treatments, and potential for further disease-modifying treatments and develop a realistic short- and long-term vision for the future clinical course, including a general sense of prognosis. With this in mind, the clinician can begin to review treatment options and help the patient decide which treatments are most likely to help meet his or her specific goals. All therapeutic options should be examined in light of the question, “Does the intervention match or assist with the patient’s treatment goals?”6 As the burden of decision-making increases near the end of life, it is important for physicians to understand their central role in helping patients make decisions. A model of shared decision-making, in which the physician provides guidance and recommendations, generally is preferred to a paternalistic approach, or, at the opposite extreme, to one in which options are presented with no guidance.7

Table 126-2 Process Steps for a Goal-Setting Family Meeting

* Laws governing surrogate decision-making vary from state to state.

Adapted from Weissman DE, Ambuel B. Establishing treatment goals, withdrawing treatments. In: Weissman DE, Ambuel B, Hallenback J, editors. Improving End-of-Life Care. 3rd ed. Milwaukee: Medical College of Wisconsin; 2000. p 101.

PROGNOSTICATION

Despite the great need for accurate prognoses, prognostication remains an elusive clinical art. Numerous empirical studies have revealed a consistent optimistic bias,8 with most physicians overestimating anticipated life span by a factor of three. Physicians’ prognostic radars are further skewed when they are more connected with the patient. Consequently, patients who are in great need of quality palliative care are referred too late to palliative care services and thus are deprived of access to good symptom management.

Given that prognostication is challenging, many physicians are uncomfortable with this task and often avoid providing realistic prognostic information, or they continue to offer futile treatment options that can convey false hope and unrealistic expectations to patients and families. When pressed by patients, physicians then typically overestimate survival. If the imminence of death is not discussed honestly, patients might be more likely to accept costly, burdensome, and futile treatments.9

Prognostication guidelines are well established for cancer.10,11 The single best prognostic variable in cancer is performance status.10,11 For example, patients with a Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) of 40 (disabled; requires special care and assistance) live on average less than 50 days; and patients with a KPS of 20 live an average of only 10 to 20 days (Table 126-3).10 Put another way, patients who are spending more than 50% of the day resting or in bed generally have a prognosis of three months or less. Specific symptoms provide further information: symptoms with an independent predictive value for a poor prognosis are shortness of breath, anorexia, difficulty swallowing, and weight loss.10

| % | LEVEL OF FUNCTIONAL CAPACITY |

|---|---|

| 100 | Normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease |

| 90 | Able to carry on normal activity, minor symptoms or signs of disease |

| 80 | Normal activity with effort, some symptoms or signs of disease |

| 70 | Cares for self, unable to carry on normal activity or to do active work |

| 60 | Requires occasional assistance, but is able to care for most needs |

| 50 | Requires considerable assistance and frequent medical care |

| 40 | Disabled, requires special care and assistance |

| 30 | Severely disabled, hospitalization is indicated although death is not imminent |

| 20 | Hospitalization is necessary; patient is very sick; active supportive treatment is necessary |

| 10 | Moribund, fatal processes progressing rapidly |

| 0 | Dead |

From Karnofsky, DA, Burchenal, JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949. p 196.

Prognostic criteria for noncancer diagnoses have been published and are especially useful to help physicians know when to refer patients for hospice services.12 Specific to gastroenterology, for example, general criteria have been established for chronic liver disease (Table 126-4). Beyond guidelines, some clinicians have advocated a simple test to determine when hospice services are appropriate by asking, “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next six months?”13,14

Table 126-4 Hospice Eligibility Criteria for End-Stage Liver Disease

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; INR, international normalized ratio.

Adapted from Standards and Accreditation Committee. Medical Guidelines for Determining Prognosis in Selected Noncancer Diseases. 2nd ed. Arlington, Va: National Hospice Organization; 1996.

No matter what type of cancer or noncancer fatal illness a person has, a “common final clinical pathway” occurs in most patients.10 Signs and symptoms that predict a prognosis of hours to days are decreased or fluctuating levels of consciousness, a precipitous clinical decline, decreased oral intake, and inability to turn over in bed.11 Patients close to death typically exhibit periods of apnea, retained oropharyngeal secretions (the death rattle), fever, and cool or mottled extremities.11

Discussing prognosis with patients and families is a key skill in palliative care. Physicians are advised to start by asking patients if they previously have been given prognostic information, if they have a sense of how much time is left, and whether they would like to discuss prognosis. If a patient indicates that he or she wishes to discuss prognostic information, provide a broad estimate, a few days to a few weeks or a few weeks to a few months, rather than, “Mr. Jones, you have only three weeks to live.”4 Once the time frame is presented, important future goals can be determined by asking, “What do you want or need to do in the time that is left?” (e.g., important events, saying goodbye to loved ones). This allows the clinician to aim the information at the level of the patient and family.11

KEY PROGNOSTIC VARIABLES AND TOOLS IN LIVER DISEASE

MODEL FOR END-STAGE LIVER DISEASE SCORES

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) (see Chapter 95) is a numeric scale used to prioritize patients for liver transplantation.15–18 It is calculated by a formula using the serum bilirubin, international normalized ratio (INR), and the serum creatinine. The MELD has been validated for short-term and intermediate-term mortality in a heterogeneous group of patients with liver disease. Modifications of the MELD score using serum sodium values have been suggested; these might enhance its prognostic ability for patients with cirrhosis.

HEPATORENAL SYNDROME

Hepatorenal syndrome (see Chapter 92) refers to functional renal failure in end-stage liver disease and is classified into two types, each with a different prognosis. Type 1 hepatorenal syndrome exhibits a rapidly progressive reduction of renal function, manifests clinically as acute renal failure, and patients have a median survival of two weeks. Type 2 hepatorenal syndrome exhibits moderate renal failure with steady or slowly progressive renal failure. These patients present with refractory ascites and have a median survival of four to six months.

MALIGNANT ASCITES

Only 10% patients who have ascites have malignancy as the primary cause; epithelial malignancies (ovary, breast, endometrial, colon, gastric, and pancreatic) cause 80% of cases. Ascites is an indicator of poor prognosis, and patients with malignant ascites have a median survival of four months. If the malignant ascites and the underlying malignancy are chemoresponsive, survival may be prolonged. Ascites is very distressing to patients and should be managed aggressively to optimize patients’ quality of life (see Chapter 91).

COMMON THEMES IN PALLIATING GASTROINTESTINAL AND HEPATIC DISEASES

A complete review of symptoms commonly experienced by patients being cared for by palliative medicine physicians is beyond the scope of this chapter. Some of the more common symptoms experienced by patients with advanced gastrointestinal and hepatic disease, and common gastrointestinal symptoms experienced by all patients at end of life, are discussed briefly in the following sections. As with all interventions, the benefit and burden of each treatment need to be evaluated in light of each patient’s goals of care. If an intervention does not help advance a patient’s individual goals of care, it should be withheld or withdrawn.14

ABDOMINAL PAIN

Diagnosis

Somatic pain typically is described as dull and achy; abdominal wall stretching from ascites is a common example. Patients describe visceral abdominal pain as poorly localized: diffuse, such as with peritonitis; referred, such as pain referred to the shoulder from hepatic disease; or colicky, such as with bowel or bile duct obstruction.19 Neuropathic abdominal pain arises from direct damage to peripheral or autonomic nerves near the spinal cord, the celiac or lumbar plexus, or more peripheral nerves. Neuropathic pain usually is described as tingling, burning, throbbing, sharp, or lancinating; abdominal pain from pancreatic cancer invading the celiac plexus is a common example.19

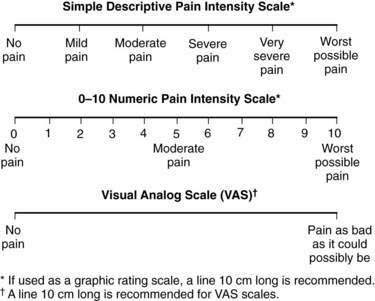

It is important to make the distinction between pain types because treatments for each type of pain may be different. A thorough pain assessment is the first step. Questions to be asked include location, duration, temporal pattern, and pain modifiers.20 Patients should be asked to rate the pain on a numeric or visual analog scale or from mild to severe (Fig. 126-1). Other important questions are drug and nondrug treatments that have been used, including their efficacy and toxicity. Finally, clinicians should assess the impact of the pain on the patient’s activities of daily living, the patient’s understanding of the cause of pain, and the patient’s specific goals for pain relief (e.g., improved sleep).21

Treatment

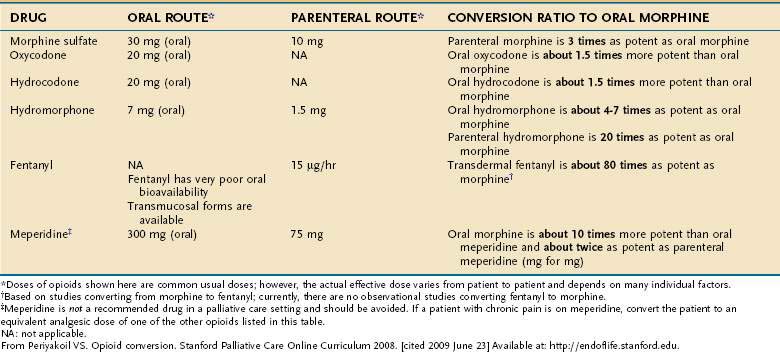

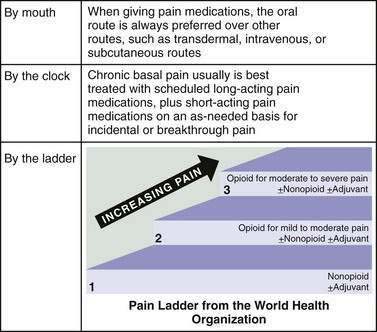

Nonpharmacologic therapies (e.g., relaxation exercises, imagery, and judicious use of heat and cold) and over-the-counter medications (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] and acetaminophen) often are adequate for mild pain. Opioids are the drugs of choice for moderate to severe pain.19 Short-acting opioids taken orally (morphine sulfate immediate release, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone) reach their peak effect in 60 to 90 minutes and provide analgesic benefit for two to four hours (Fig. 126-2, Table 126-5).19 There is no ceiling dose of opioids, but combination products containing acetaminophen, aspirin, or NSAIDs have a ceiling based on the toxicity profile of the nonopioid.19

Figure 126-2. Opioid therapy for patients with chronic severe pain.

(From Periyakoil VS. Opioid conversion. Stanford Palliative Care Online Curriculum 2008. [cited 2009 June 23] Available at: http://endoflife.stanford.edu.)

Long-acting oral opioid preparations (morphine or oxycodone continuous release) provide 8 to 12 hours of analgesia.19 Transdermal fentanyl offers 72 hours of pain relief and is a good option for patients with stable opioid requirements who cannot take oral medications.21 Transdermal fentanyl takes 12 to 24 hours to reach full effect, and analgesia and toxicities last for up to 24 hours after removal of a patch.21 A small percentage of patients need to replace the patch before 72 hours; cases of withdrawal occurring between 48 and 72 hours have been reported.18,22

All patients receiving a long-acting opioid preparation also need a short-acting opioid for breakthrough pain. One method for calculating the size of the dose for breakthrough pain is to take 10% to 20% of the 24-hour daily opioid dose, given every 1 to 4 hours as needed.19 For example, if a patient is using 120 mg a day of long-acting morphine, an appropriate breakthrough dose would be morphine sulfate immediate release, 15 mg orally every 1 to 4 hours as needed.

The oral route is preferred for opioid administration based on availability, cost, and ease of use.19 For those with difficulty swallowing, many of the short-acting oral opioids come in concentrated solutions.19 Fentanyl also comes in a candy matrix on an applicator stick that can be twirled against the buccal mucosa for absorption, and it comes in a buccal tablet; it has a quick onset and is an option for breakthrough pain.19,23 Morphine and hydromorphone can be administered rectally, in the same dosages as used orally, with analgesic benefit similar to that in the oral route.19

Patients unable to take medications by oral, sublingual, transdermal, or rectal routes or patients in need of rapid pain control benefit from an intravenous or subcutaneous infusion.19 Dosage by the subcutaneous route is equivalent to that by the intravenous route.19 Morphine or hydromorphone can be given subcutaneously, either as periodic injections or by a continuous infusion.19 Intramuscular injections are never indicated; they are unnecessarily painful, and absorption can be erratic.19

Opioid toxicities are predictable and often resolve without treatment. Opioids can cause nausea when the drug is initiated or the dose is increased, but this almost always resolves within a few days. Nausea that occurs when patients have been on a stable dosage of opioid for a prolonged period (more than one week) rarely is related to the opioid but can occur in patients on very high doses.24 There is no proven best treatment for opioid-induced nausea; starting with a low-cost dopamine antagonist (e.g., prochlorperazine) is a reasonable first step.

Tolerance to the analgesic effects of opioids is uncommon; in most patients, increasing pain indicates increasing pathology.25 Physical dependence is universal: all patients on chronic opioids for more than several weeks can be expected to develop some signs of opioid withdrawal if the opioid is discontinued or an antagonist is administered.26 A difficult diagnostic dilemma can arise in patients with underlying abdominal pain, because cramping abdominal pain is a symptom of opioid withdrawal. Psychological dependence (i.e., addiction) is rare in patients who have chronic pain and no history of addiction; the hallmark of addiction is the use of drugs despite harmful effects and loss of control of drug use.26 A physician’s fear of causing addiction in a dying patient is not a rational reason to withhold opioids.26

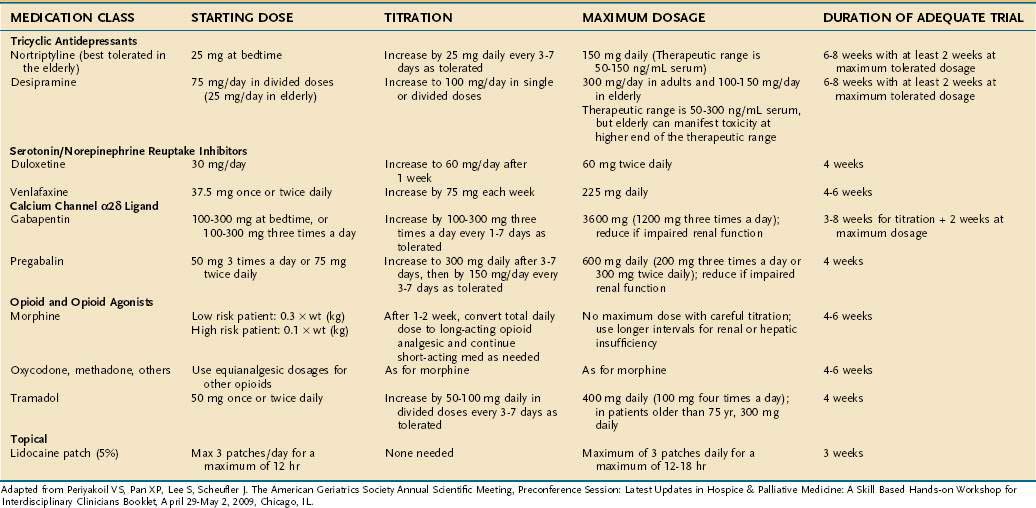

Many patients benefit from adjuvant analgesics, defined as nonopioid drugs used to enhance the effectiveness of opioids or drugs specifically used for neuropathic pain.19 Examples include NSAIDs or corticosteroids for somatic pain23,27 and tricyclic antidepressants and antiseizure drugs for neuropathic pain.28 When oral and intravenous medications fail to provide adequate analgesia, anesthetic procedures should be explored, including autonomic blockade (e.g., celiac plexus block29) or epidural or intrathecal anesthesia.30 All patients can benefit from nonpharmacologic treatments, including relaxation exercises, imagery, and judicious use of heat or cold.31 An abbreviated list of adjuvant analgesics for neuropathic pain is provided in Table 126-6.

Acute and chronic abdominal pain are covered in Chapters 10 and 11, respectively.

NAUSEA AND VOMITING

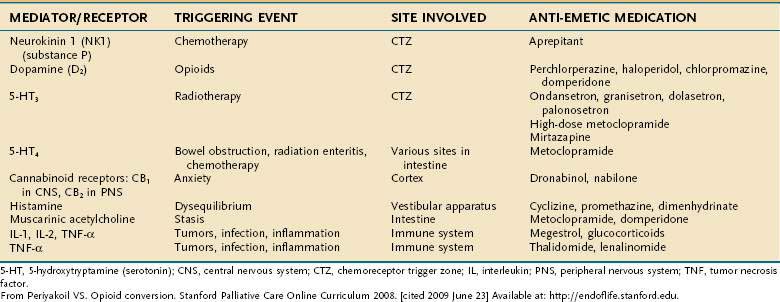

Nausea is a highly prevalent symptom24,32 and a challenging one to manage in palliative care patients. Causes of nausea and vomiting in this population are often multifactorial and due to gastrointestinal causes (gastroparesis, gastric compression, dysmotility, constipation, bowel obstruction), CNS causes (brain metastases, anxiety, vestibular dysfunction), hepatic or renal dysfunction, and medications (opioids). Cancer chemotherapy and radiation therapy also often precipitate nausea. Many palliative care experts favor a mechanistic approach33 to management based on the likely etiology and target therapy based on the specific neurotransmitter involved (Table 126-7); others recommend an empirical approach. Evidence supporting the existing consensus-based guidelines for managing nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer is sparse. Well-designed studies of the impact of standard management and novel agents on nausea and vomiting in palliative care populations are needed.34

ANOREXIA AND CACHEXIA

Anorexia is defined as loss of appetite, especially from disease; cachexia is defined as weight loss and wasting, particularly of muscle mass, and is accompanied by the general debility that can occur with chronic illness.35 These entities often are combined into the anorexia-cachexia syndrome, a term usually referring to cancer-related anorexia and cachexia,36 although this symptom complex can occur in patients with serious illness from any cause. Anorexia-cachexia syndrome is reported in up to 80% of cancer patients and represents a poorly understood neuroendocrine and metabolic disorder.36,37

Involuntary weight loss is associated with decreased functional status, decreased response to chemotherapy, and decreased survival. Although the anorexia-cachexia syndrome itself is not painful, patients and families experience emotional suffering given the cultural significance of food intake; the loss of weight and inability to eat are a daily reminder of the illness experience and impending death.37,38 The syndrome contributes to fatigue, increased complications of antineoplastic treatments, and decreased survival. Weight loss itself is an independent risk factor for mortality.37

Aggressive nutritional supplementation in patients with advanced malignancy provides no survival benefit, no improvement in tumor shrinkage, and only minimal decrease in toxicity from antineoplastic treatments.37 Patients and families often want to continue enteral or parenteral nutrition and hydration to provide the sense of “offering comfort” and to prevent their loved one from “starving to death.”39 Attempts to provide such hydration and nutrition, however, can make the goal of comfort harder to achieve in the dying patient. Nasogastric and gastrostomy tubes are uncomfortable at the end of life; intravenous delivery of nutrition necessitates intravenous access; restraints are commonly needed to maintain access; and such nutrition and hydration increase the patient’s fluid volume, which in patients close to death can worsen ascites, pleural effusions, and peripheral edema.40

Appetite stimulants have a limited role in patients with advanced cancer. Indications for starting an appetite stimulant include a prognosis of longer than four weeks combined with the patient’s interest in regaining appetite. No drug has shown efficacy in prolonging survival or improving quality of life in population-based research, although individual patients might gain weight and have a greater sense of well-being.38 The progestational agent megestrol acetate has been well studied.41 At doses of 160 to 800 mg/day, megestrol results in a greater than 5% weight gain in 20% to 30% of patients with advanced cancer, the weight gain being adipose tissue, not muscle41; if improvement is not seen in two to four weeks, discontinuation of the drug is appropriate.41 Glucocorticoids can lead to weight gain, but the well-known toxicities of these agents often preclude anything but their short-term use.38 Other agents currently under investigation include eicosapentaenoic acid, dronabinol, testosterone, thalidomide, adenosine triphosphate, and NSAIDs.41,42

CONSTIPATION

Constipation43–47 is very common and highly distressing symptom in palliative care patients. It is reported in more than 50% of patients43–44 on a palliative care or hospice unit, a percentage that probably underestimates its true prevalence.45 In seriously ill and dying patients, the most common precipitants of constipation are poor fluid intake, immobility, autonomic failure, and use of opioid and anticholinergic medications.

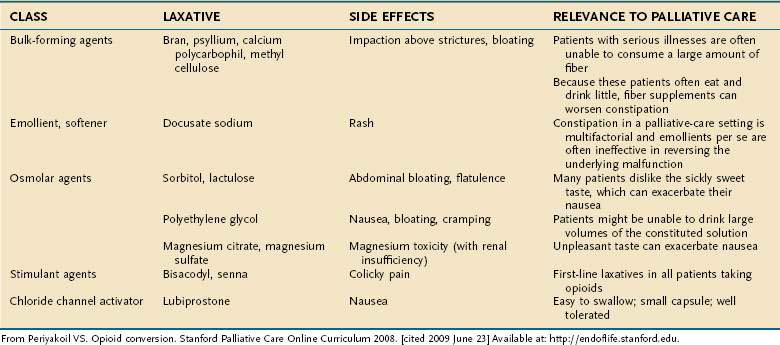

More than 90% of patients on opioid medications experience constipation.47 Opioids bind to mu receptors on the smooth muscle of the bowel, suppressing peristalsis and raising anal sphincter tone. In one study, patients using transdermal fentanyl used laxatives less than patients using oral morphine, indicating that transdermal fentanyl may be less constipating than other opioids.48 Although a stool softener can help lubricate hard stool, a bowel stimulant such as senna usually is necessary as both a prophylactic drug for opioid constipation and for initial therapy of established constipation. A commonly recommended regimen in the hospice literature is to start with senna, escalating as necessary; if no bowel movement is obtained in three days, bisacodyl or an enema (phosphosoda) is recommended.46 More refractory constipation can be relieved with magnesium citrate, a sorbitol-based product, or small doses of polyethylene glycol. Fiber supplements can lead to obstipation or obstruction and are not recommended for palliative care unless patients also are typically able to ingest large quantities of water.

Orally administered opioid antagonists may be effective in reversing opioid-related constipation in patients for whom other therapies are not effective.45 Parenteral opioid antagonists that do not cross the blood-brain barrier are most effective in reversing the opioid effects on the intestine. Methylnaltrexone49,50 has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for chronic opioid-induced constipation. The methylation of naltrexone prevents it from crossing the blood-brain barrier and thereby reversing the central analgesic effects of opioids.

When patients are actively dying—that is, death is expected within one to two weeks—and they have no abdominal symptoms, aggressive drug therapy to cause laxation on a regular basis is not indicated. In fact, laxatives that cause cramping or any suppositories or enemas usually increases patient discomfort and can be withheld (Table 126-8).

DIARRHEA

Diarrhea is less common than constipation and is reported in up to 10% of hospice patients.43 Although the differential diagnosis for diarrhea is broad, two common causes in the palliative care patient are overuse of laxative therapy and diarrhea secondary to leakage of stool around a fecal impaction.44,45

Treatment is directed at the cause of diarrhea. Octreotide51 is useful for refractory diarrhea (particularly with endocrine tumors such as VIPomas and gastrinomas), although it is quite costly. Replacement of pancreatic enzymes is helpful in cases of malabsorption following pancreatic cancer surgery. Cholestyramine (binding of bile salts) and aspirin (reduction of prostaglandin synthesis thus decreasing water and electrolyte secretion) may be beneficial in secretory diarrhea induced by radiation colitis.52 Opioids or opioid-like medications (e.g., loperamide) might offer the best symptomatic relief.

INTESTINAL OBSTRUCTION

Malignant bowel obstruction is seen most commonly as a complication of cancers of the colon, ovary, pancreas, and stomach.53 Obstruction results from either intraluminal or extraluminal tumor. Benign causes, such as adhesions, radiation bowel damage, inflammatory bowel disease, opioid-induced impaction, or hernia also can cause obstruction.53–55 Intestinal obstruction can occur in the small or large bowel or in both sites; multifocal obstructions are common.54,55

The symptoms of intestinal obstruction are nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, constipation, and colicky abdominal pain.56 Nasogastric suction is used to provide temporary relief; in many cases, just a few days of nasogastric suction may convert a complete obstruction to a partial one or might even resolve an obstruction.57 Surgery with a primary anastomosis, stoma (e.g., colostomy, ileostomy), or endoluminal stenting are the preferred options for managing obstruction; the morbidity from major abdominal surgery in cancer patients with bowel obstruction is high.58

Despite the advances in surgery and the growing use of endoluminal stents, such procedures are not possible for many patients.53 Medical management using drugs is effective at reducing the symptom burden of inoperable obstructions. The goals of pharmacologic therapy are reducing distressing symptoms, avoiding the need for parenteral hydration, and removing nasogastric suction. Pharmacologic treatments consist of a cocktail of drugs including opioids for abdominal pain, dopamine antagonist antiemetics such as phenothiazines or butyrophenones for nausea, and antisecretory drugs (octreotide) to reduce colicky pain and reduce intestinal secretions.59–63 A prokinetic agent such as metoclopramide can provide relief for an incomplete or functional obstruction but should be avoided in complete obstruction.57

JAUNDICE

Although jaundice64 is usually an ominous sign in patients with cancer, it might have a correctable cause. The goal of pursuing an evaluation of jaundice is to determine if there are conditions amenable to treatment in which the burden-to-benefit ratio is favorable, given the underlying extent of cancer. Interventional procedures65 for biliary obstruction, such as surgical bypass of the biliary tract or endoscopic placement of biliary stents, may be useful early in the disease course when patients have a good performance status, but their utility becomes less as performance status declines and the burden of stent placement with its potential for various complications increases.

Pruritus commonly is associated with jaundice. Cool temperatures, lower humidity, and topical agents like astringents, moisturizers, and steroid creams can provide relief. Both H1 and H2 antihistamines, phenothiazines, and bile acid resins have been used with some effectiveness. Opioid antagonists also have been used to treat pruritus, but their systemic use reverses analgesia in many patients receiving opioids.66–70 Gabapentin and butorphanol are effective in palliating uremic pruritus, which usually does not respond to antihistamines. Rifampin has been used to palliate pruritus, but its use may be limited by its risk for causing hepatitis.

ASCITES

Between 15% and 50% of patients with cancer develop ascites, most commonly from ovarian, endometrial, breast, large bowel, stomach, and pancreatic cancers.71,72 Malignant ascites portends a poor prognosis, with a one-year survival of 40% and three-year survival of less than 10%.64 The well-known list of nonmalignant causes of ascites, including portal vein thrombosis, congestive heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, and pancreatitis, should be considered before assuming malignancy is the reason for the patient’s ascites. Symptoms of ascites include an increase in abdominal girth, bloating, abdominal wall pain, nausea, anorexia, and dyspnea.

Paracentesis should be performed to evaluate new-onset ascites if the intervention will lead to a change in therapy or if the paracentesis will provide symptomatic benefit. Repeated therapeutic paracentesis, with or without an indwelling peritoneal catheter, is the most commonly used invasive treatment for malignant ascites.64 Peritoneovenous shunts73 have a better success rate in patients with nonmalignant ascites than in patients with malignant ascites but are infrequently used today. Octreotide has been reported to provide symptomatic benefit in malignant ascites, but its cost may be prohibitive.74,75

HEPATIC ENCEPHALOPATHY

Hepatic encephalopathy is associated with poor prognosis. Two studies76–77 have shown that the cumulative survival in these patients was very short: approximately 20% to 40% at one year and 15% at three years of follow-up. Hepatic encephalopathy due to hepatic metastases is uncommon unless there is an overwhelming liver tumor burden and is usually a terminal event. Aggressive attempts at reversal usually are futile except for a very short-term benefit, which for some patients may be needed to help bring family closure. When death is near, clinicians should use opioid analgesics and other sedating medication liberally for control of distressing symptoms, even if such treatments worsen the encephalopathy. Family and staff counseling at this time are important to ensure that all parties share the same goals of care.

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Few events are as traumatic for families caring for their loved one as observing a massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage.78 If gastrointestinal bleeding is considered a likely future event, the key is to discuss care options and to develop a plan to provide patients and families with a sense of control for what can seem to be an out-of-control situation. If the patient has advanced disease and is dying, the focus should be toward comfort rather than toward diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Having dark-colored towels and sheets available to camouflage the bleeding is helpful, along with a rapidly acting sedating medication for emergency use. Some experts recommend chlorpromazine 25 mg given as a slow intravenous push or a 50 mg suppository rectally. Education and support of the family is of great importance, especially when the patient is dying at home.

Abrahm JL. Nonpharmacologic strategies for pain and symptom management. In: Abrahm JL, editor. A Physician’s Guide to Pain and Symptom Management in Cancer Patients. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000:247. (Ref 31.)

American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Fellowship programs. [cited 2009 June 23] Available from http://www.aahpm.org/fellowship/index.html (Ref 5.)

Baron TH. Palliation of malignant obstructive jaundice. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35:101-12. (Ref 65.)

Bruera E, Sweeney C. Chronic nausea and vomiting. In: Berger AM, Portenoy RK, Weissman DE, editors. Principles and Practice of Palliative Care and Supportive Oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:222. (Ref 33.)

Chappell D, Rehm M, Conzen P. Methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1071. (Ref 49.)

Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in physicians’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study. West J Med. 2000;172:310-13. (Ref 8.)

Farrar JT, Portenoy RK. Neuropathic cancer pain: The role of adjuvant analgesics. Oncology (Williston Park). 2001;15:1435-42. 45. (Ref 28.)

Huo TI, Lin HC, Huo SC, et al. Comparison of four model for end-stage liver disease–based prognostic systems for cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:837-44. (Ref 18.)

Huo TI, Wu JC, Lin HC, et al. Evaluation of the increase in model for end-stage liver disease (DeltaMELD) score over time as a prognostic predictor in patients with advanced cirrhosis: risk factor analysis and comparison with initial MELD and Child-Turcotte-Pugh score. J Hepatol. 2005;42:826-32. (Ref 17.)

Kichian K, Bain VG. Jaundice, Ascites and Hepatic Encephalopathy. In: Doyle D, Hank SG, Cherny N, Calman K, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:507. (Ref 64.)

Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1096-105. (Ref 11.)

Ripamonti CI, Easson AM, Gerdes H. Management of malignant bowel obstruction. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1105-15. (Ref 75.)

Said A, Williams J, Holden J, et al. Model for end stage liver disease score predicts mortality across a broad spectrum of liver disease. J Hepatol. 2004;40:897-903. (Ref 15.)

Srikureja W, Kyulo NL, Runyon BA, et al. MELD score is a better prognostic model than Child-Turcotte-Pugh score or Discriminant Function score in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2005;42:700-6. (Ref 16.)

World Health Organization. Definition of palliative care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [cited 2009 June 23] Available from http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (Ref 1.)

1. World Health Organization. Definition of palliative care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [cited 2009 June 23] Available from http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

2. World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Report No.: 804. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990.

3. Putnam A, Palliative Billings J. medicine. In: Ballantyne J, Fishman S, Abdi S, editors. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of Pain Management. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2002:479.

4. Storey P, Knight C. UNIPAC One: The hospice/palliative medicine approach to end-of-life care. New Rochelle, NY: Mary Ann Liebert; 2003.

5. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Fellowship programs. [cited 2009 June 23] Available from http://www.aahpm.org/fellowship/index.html

6. Weissman DE, Ambuel D. Establishing treatment goals, withdrawing treatments. In: Weissman DE, Ambuel B, Hallenback J, editors. Improving end-of-life care. 3rd ed. Milwaukee: Medical College of Wisconsin; 2000:101.

7. Quill TE, Brody H. Physician recommendations and patient autonomy: Finding a balance between physician power and patient choice. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(9):763-9.

8. Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in physicians’ prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study. West J Med. 2000;172(5):310-13.

9. Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1709-14.

10. Reuben DB, Mor V, Hiris J. Clinical symptoms and length of survival in patients with terminal cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148(7):1586-91.

11. Lamont EB, Christakis NA. Prognostic disclosure to patients with cancer near the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(12):1096-105.

12. Standards and Accreditation Committee Medical Guidelines Task Force. Medical guidelines for determining prognosis in selected noncancer diseases. Arlington, Va: National Hospice Organization; 1996.

13. Lynn J, Schuster JL, Kabcenell A. Improving care for the end of life: A sourcebook for health care managers and clinicians. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000.

14. Lo B. Futile interventions. In: Lo B, editor. Resolving ethical dilemmas: A guide for clinicians. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:72.

15. Said A, Williams J, Holden J, et al. Model for end stage liver disease score predicts mortality across a broad spectrum of liver disease. J Hepatol. 2004;40(6):897-903.

16. Srikureja W, Kyulo NL, Runyon BA, et al. MELD score is a better prognostic model than Child-Turcotte-Pugh score or Discriminant Function score in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2005;42(5):700-6.

17. Huo TI, Wu JC, Lin HC, et al. Evaluation of the increase in model for end-stage liver disease (DeltaMELD) score over time as a prognostic predictor in patients with advanced cirrhosis: Risk factor analysis and comparison with initial MELD and Child-Turcotte-Pugh score. J Hepatol. 2005;42(6):826-32.

18. Huo TI, Lin HC, Huo SC, et al. Comparison of four model for end-stage liver disease-based prognostic systems for cirrhosis. Liver Transpl. 2008;14(6):837-44.

19. Thomas JR, von Gunten CF. Pain in terminally ill patients: Guidelines for pharmacological management. CNS Drugs. 2003;17(9):621-31.

20. Weissman DE. Pain management. In: Weissman DE, Ambuel B, Hallenback J, editors. Improving end-of-life care. 3rd ed. Milwaukee: Medical College of Wisconsin; 2000:23.

21. Lehmann KA, Zech D. Transdermal fentanyl: Clinical pharmacology. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7(3 Suppl):S8-16.

22. Ripamonti C, Campa T, De Conno F. Withdrawal symptoms during chronic transdermal fentanyl administration managed with oral methadone. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27(3):191-4.

23. Coluzzi PH, Schwartzberg L, Conroy JD, et al. Breakthrough cancer pain: A randomized trial comparing oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC) and morphine sulfate immediate release (MSIR). Pain. 2001;91(1-2):123-30.

24. Bruera E, Seifert L, Watanabe, et al. Chronic nausea in advanced cancer patients: A retrospective assessment of a metoclopramide-based antiemetic regimen. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;11(3):147-53.

25. Collin E, Poulain P, Gauvain-Piquard A, et al. Is disease progression the major factor in morphine “tolerance” in cancer pain treatment? Pain. 1993;55(3):319-26.

26. Sees KL, Clark HW. Opioid use in the treatment of chronic pain: assessment of addiction. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1993;8(5):257-64.

27. Mercadante S, Casuccio A, Agnello A, et al. Analgesic effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in cancer pain due to somatic or visceral mechanisms. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17(5):351-6.

28. Farrar JT, Portenoy RK. Neuropathic cancer pain: The role of adjuvant analgesics. Oncology (Williston Park). 2001;15(11):1435-42. 45

29. Wong GY, Schroeder DR, Carns PE, et al. Effect of neurolytic celiac plexus block on pain relief, quality of life, and survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(9):1092-9.

30. Swarm RA, Karanikolos M, Cousins RJ. Anaesthetic techniques for pain control. In: Doyle D, Hank SG, Cherny N, Calman K, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:378.

31. Abrahm JL. Nonpharmacologic strategies for pain and symptom management. In: Abrahm JL, editor. A physician’s guide to pain and symptom management in cancer patients. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2000:247.

32. Baines MJ. ABC of palliative care. Nausea, vomiting, and intestinal obstruction. BMJ. 1997;315(7116):1148-50.

33. Bruera E, Sweeney C. Chronic nausea and vomiting. In: Berger AM, Portenoy RK, Weissman DE, editors. Principles and practice of palliative care and supportive oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:222.

34. Glare P, Pereira G, Kristjanson LJ, et al. Systematic review of the efficacy of antiemetics in the treatment of nausea in patients with far-advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12(6):432-40.

35. Hensyl WR, editor. Stedman’s medical dictionary, 25th ed, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1990.

36. Strasser F. Pathophysiology of the anorexia/cachexia syndrome. In: Doyle D, Hank SG, Cherny N, Calman K, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:520.

37. Bruera E. ABC of palliative care. Anorexia, cachexia, and nutrition. BMJ. 1997;315(7117):1219-22.

38. Fainsinger RL, Pereira J. Clinical assessment and decision making in cachexia and anorexia. In: Doyle D, Hank SG, Cherny N, Calman K, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:533.

39. Ambuel B, Weissman DE. Establishing treatment goals, withdrawing treatments. In: Weissman DE, Ambuel B, Hallenback J, editors. Improving end-of-life care. 3rd ed. Milwaukee: Medical College of Wisconsin; 2000:103.

40. Lanuke K, Fainsinger RL, DeMoissac D. Hydration management at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(2):257-63.

41. Salacz M. Megestrol acetate for cancer anorexia cachexia 2003. Fast Facts and Concepts #100. [cited 2009 June 23] Available from http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/fastFact/ff_100.htm

42. Jatoi AJr, Loprinzi CL. Current management of cancer-associated anorexia and weight loss. Oncology (Williston Park). 2001;15(4):497-502.

43. Sykes N. Constipation and diarrhea. In: Doyle D, Hank SG, Cherny N, Calman K, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:483.

44. Curtis EB, Krech R, Walsh TD. Common symptoms in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Care. 1991;7(2):25-9.

45. Mazuryk M. The clinical assessment of the patient with gastrointestinal symptoms. In: Ripamonti C, Bruera E, editors. Gastrointestinal symptoms in advanced cancer patients. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002:17.

46. Levy M. Constipation and diarrhea in cancer patients: I. Prim Care. Cancer. 1992;12:11.

47. Mancini I, Bruera E. Constipation in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1998;6(4):356-64.

48. Radbruch L, Sabatowski R, Loick G, et al. Constipation and the use of laxatives: A comparison between transdermal fentanyl and oral morphine. Palliat Med. 2000;14(2):111-19.

49. Chappell D, Rehm M, Conzen P. Methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(10):1071.

50. Chappell D, Rehm M, Conzen P. Opioid-induced constipation in intensive care patients: Relief in sight? Crit Care. 2008;12(4):161.

51. Mercadante S. Diarrhea in terminally ill patients: Pathophysiology and treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10(4):298-309.

52. Mercadante S. Diarrhea, malabsorption and constipation. In: Berger AM, Portenoy RK, Weissman DE, editors. Principles and practice of palliative care and supportive oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002:233.

53. Sainsbury R, Vaizey C, Pastorino U. Surgical palliation. In: Doyle D, Hank SG, Cherny N, Calman K, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:255.

54. Feuer DJ, Broadley KE, Shepherd JH, et al. Systematic review of surgery in malignant bowel obstruction in advanced gynecological and gastrointestinal cancer. The Systematic Review Steering Committee. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75(3):313-22.

55. Ripamonti C, Bruera E. Palliative management of malignant bowel obstruction. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12(2):135-43.

56. Mercadante S. Pain in inoperable bowel obstruction. Pain. 1995;5:9. digest

57. Ripamonti C, Mercadante S. Pathophysiology and management of malignant bowel obstruction. In: Doyle D, Hank SG, Cherny N, Calman K, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:496.

58. Ripamonti C, Mercadante S, Groff L, et al. Role of octreotide, scopolamine butylbromide, and hydration in symptom control of patients with inoperable bowel obstruction and nasogastric tubes: A prospective randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(1):23-34.

59. Mercadante S, Ripamonti C, Casuccio A, et al. Comparison of octreotide and hyoscine butylbromide in controlling gastrointestinal symptoms due to malignant inoperable bowel obstruction. Support Care Cancer. 2000;8(3):188-91.

60. Mercadante S, Maddaloni S. Octreotide in the management of inoperable gastrointestinal obstruction in terminal cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1992;7(8):496-8.

61. Khoo D, Riley J, Waxman J. Control of emesis in bowel obstruction in terminally ill patients. Lancet. 1992;339(8789):375-6.

62. Riley J, Fallon MT. Octreotide in terminal malignant obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. Eur. J Palliat Care. 1994;1:23.

63. Mangili G, Franchi M, Mariani A, et al. Octreotide in the management of bowel obstruction in terminal ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;61(3):345-8.

64. Kichian K, Bain VG. Jaundice, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy. In: Doyle D, Hank SG, Cherny N, Calman K, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004:507.

65. Baron TH. Palliation of malignant obstructive jaundice. Gastroenterol Clin North Am.. 2006;35(1):101-12.

66. Khandelwal M, Malet PF. Pruritus associated with cholestasis. A review of pathogenesis and management. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39(1):1-8.

67. Bergasa NV, Talbot TL, Alling DW, et al. A controlled trial of naloxone infusions for the pruritus of chronic cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102(2):544-9.

68. Jones EA, Bergasa NV. The pruritus of cholestasis and the opioid system. JAMA. 1992;268(23):3359-62.

69. Wolfhagen FH, Sternieri E, Hop WC, et al. Oral naltrexone treatment for cholestatic pruritus: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(4):1264-9.

70. Bergasa NV, Schmitt JM, Talbot TL, et al. Open-label trial of oral nalmefene therapy for the pruritus of cholestasis. Hepatology. 1998;27(3):679-84.

71. Runyon BA, Hoefs JC, Morgan TR. Ascitic fluid analysis in malignancy-related ascites. Hepatology. 1988;8(5):1104-9.

72. Lifshitz S. Ascites, pathophysiology and control measures. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1982;8(8):1423-6.

73. Holm A, Halpern NB, Aldrete JS. Peritoneovenous shunt for intractable ascites of hepatic, nephrogenic, and malignant causes. Am J Surg. 1989;158(2):162-6.

74. Cairns W, Malone R. Octreotide as an agent for the relief of malignant ascites in palliative care patients. Palliat Med. 1999;13(5):429-30.

75. Ripamonti CI, Easson AM, Gerdes H. Management of malignant bowel obstruction. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(8):1105-15.

76. Amodio P, Del Piccolo F, Petteno E, et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of quantified electroencephalogram (EEG) alterations in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2001;35(1):37-45.

77. Bustamante J, Rimola A, Ventura PJ, et al. Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1999;30(5):890-5.

78. Christensen E, Krintel JJ, Hansen SM, et al. Prognosis after the first episode of gastrointestinal bleeding or coma in cirrhosis. Survival and prognostic factors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24(8):999-1006.