chapter 23 Palliative Care

The Broad Scope of Palliative Care

This chapter is designed to help you develop the following clinical skills:

BOX 23–1 Clinical Skills to Bring to the Bedside of Every Patient (Living or Dying)

Assessing pain across the pediatric age spectrum

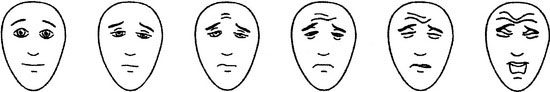

Pain assessment in pediatrics can be complex and is determined by the developmental capacity of the verbal child. Most 7- to 8-year-old children are able to describe the intensity of their pain using a simple 0 to 10 numeric rating, making sure they understand the anchors of 0 being no pain at all and 10 being the most pain they have had or could imagine having. A younger child, starting at about age 4, is able to self-report pain intensity using a visual analog scale, such as the Revised Faces Pain Scale (Fig. 23–1). Find out and use the words that each child uses for pain, such as “owie” or “ouch” when asking about the child’s pain.

FIGURE 23–1 Revised Faces Pain Scale. Faces from left to right correspond with a score of 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10.

(From Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, et al: The faces pain scale—revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain 93:173–183, 2001. Used with permission from IASP.)

Provide effective pain and symptom management

Kate’s codeine was stopped, and morphine, along with a bowel regimen, was started.

Address concerns of addiction and safety

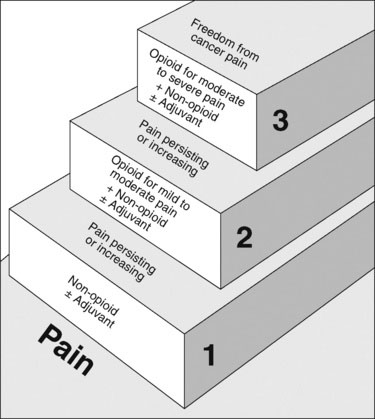

FIGURE 23–2 The World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder.

(Modified from the World Health Organization: Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care in Children. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 1998.)

Parent: OK, fair enough, but won’t she continue to need higher doses?

The importance of courage and honesty when having difficult conversations

Sharing bad news

When reviewing the status of the illness and goals of care:

http://www.act.org.uk/index.php/shop.html. A Guide to the Development of Children’s Palliative Care Services www.act.org.uk

http://www.cnpcc.ca. Canadian Network of Palliative Care for Children provides a wealth of resource material http://www.cnpcc.ca

http://www.virtualhospice.ca. Comprehensive palliative care resources for patients and health care professionals http://www.virtualhospice.ca

http://www.eperc.mcw.edu End of Life/Palliative Education Resource Center (from the Medical College of Wisconsin) offers an excellent searchable database of palliative care educational resources and Fast Facts http://www.eperc.mcw.edu

http://childrenoflifecare.org Excellent resources from Texas Children’s Hospital, including video interviews http://childendoflifecare.org

http://www.griefworksbc.com The Dougy Center offers extensive information and resources for grieving children, teens, and young adults and their families www.dougy.org

Frager G., Blake B. When palliative care involves children: Talking with the child as family member and as a patient—pain and symptoms highlights. In: MacDonald N., Oneschuk D., Hagen N., et al, editors. Palliative Medicine: A Case-Based Manual. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005:271-294.

Hicks C.L., von Baeyer C.L., Spafford P.A., et al. The faces pain scale—revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93:173-183.

Hurwitz C.A., Duncan J., Wolfe J. Caring for the child with cancer at the close of life; “There are people who make it, and I’m hoping I’m one of them”. JAMA. 2004;292:2141-2149.

Mack J.W., Hilden J.M., Watterson J., et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9155-9161.

Meyer E.C., Ritholz M.D., Burns J.P., et al. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents’ priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):649-657.

Pantilat S. Communicating with seriously ill patients: Better words to say. JAMA. 2009;301:1279-1281.

World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care in Children. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1998.