7 Palliative care

Pain management

Assessment of pain

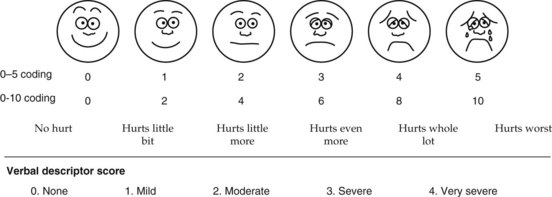

It is important to assess the multidimensional nature of pain. Intensity of pain, location, duration and factors that modify pain should be assessed. There are various tools to assess the pain and the commonly used ones are shown in Box 7.1.

Management of pain

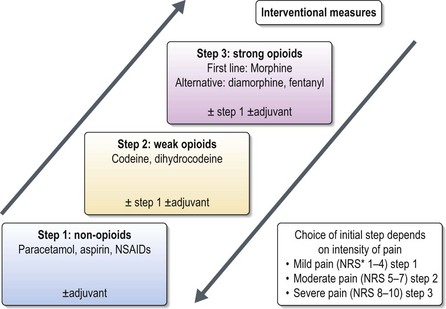

The management of pain includes analgesics as well as non-pharmacological measures. The World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder (Figure 7.1) has been the gold standard in the management of pain and has been shown to eliminate pain in 80% of patients. The remaining 20% have complex pain which may require specialist interventions. Measures used in complex pain include neuro-anaesthetic interventions, palliative surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and psychosocial care.

Analgesics

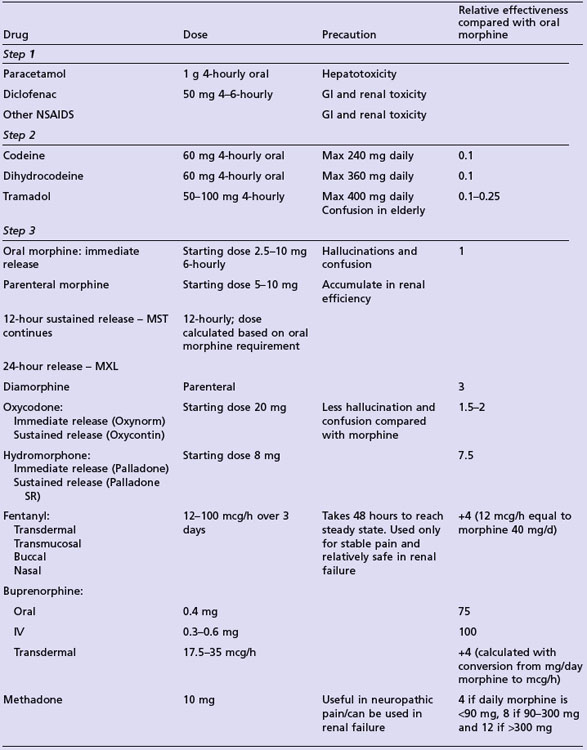

Commonly used analgesics are given in Table 7.1. Strong opioids are started at a low dose and titrated according to the clinical need (Box 7.2). Morphine is the strong agent of choice and oral administration is preferred. Transdermal preparations are useful only in stable pain. Some agents may only be prescribed by specialists in palliative care medicine or anaesthetia.

Box 7.2

Titration of opioid dose

Step 1

Opioid side effects, toxicity and management

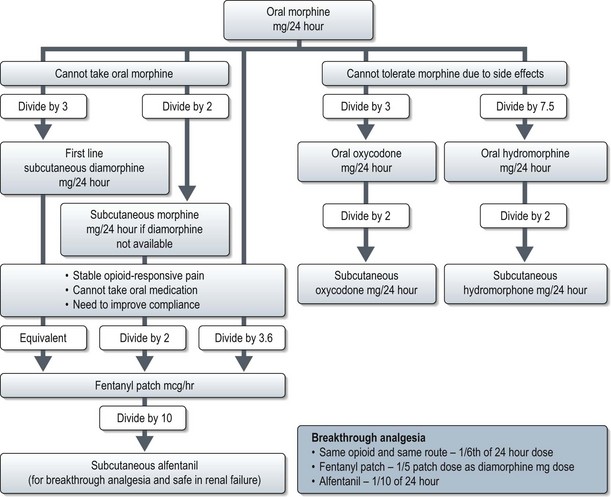

All patients feel some degree of drowsiness when starting or increasing their dosage. This usually wears off 3–5 days after being on a stable dose. Constipation is inevitable and 30–50% patients develop nausea and vomiting; these symptoms should be managed prophylactically. Intolerable side effects necessitate switching to an alternative opioid (Figure 7.2).

Opioid toxicity usually manifests pseudo-hallucinations (shadows at the peripheries of the field of vision), myoclonic jerks, cognitive impairment, and visual and auditory hallucinations. Initial management includes adequate hydration (dehydration is often a precipitant of toxicity), reduction of opioid and haloperidol (1.5–3 mg oral) for cognitive impairment. If the patient has persistent toxicity without adequate analgesia, opioid switching is needed (Figure 7.2). Though there is no best choice, oxycodone and hydromorphone are the usual alternatives. Naloxone is a short acting opioid antagonist used intravenously for reversing accidental severe opioid overdose.

Adjuvant analgesics

Adjuvant analgesics (Table 7.2) are a useful complement to regular analgesics in complex pain. These include anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antispasmodics, bisphosphonates, steroids, muscle relaxants and N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist (ketamine).

| Indication | Drug | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropathic pain | Dexamethasone | 8–16 mg daily |

| Gabapentin | 100–300 mg (nocte) Titrate to 600 mg TDS | |

| Amitriptyline |

Complex pain

Neuropathic pain is often difficult to control. Agents useful to control neuropathic pain are shown in Table 7.2. Amitryptyline along with regular analgesics is the first line management. If pain is not adequately controlled, gabapentin can be either added to amitryptyline or used as substitute. In nerve compression pain steroids or TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) can be considered. Ketamine is useful if these measures fail to control pain. If pain continues to be a problem neuro-anaesthetic interventions such as neural blockade (nerve block, epidural opioids) or neurodestruction (as a last resort) are considered.

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are the most common symptoms in cancer management. A thorough clinical assessment including detailed history and examination to establish the cause and severity is important. Possible causes include treatment related (chemotherapy, radiotherapy or other drugs), gastrointestinal pathology (e.g. obstruction), electrolyte abnormalities (e.g. hypercalcaemia), and brain metastases. Investigations are governed by findings from history, clinical examination, and a review of the drug chart and chemotherapy prescription. First-line treatment depends on the possible cause and examples are given in Table 7.3. Levomepromazine (6.25–25 mg subcutaneous per day) and dexamethasone are used as second line treatment.

Table 7.3 Agent of choice in nausea and vomiting based on cause

| Cause | Treatment – first line anti-emetic |

|---|---|

| Chemotherapy |

Depression

End-of-life care

End-of-life care of the cancer patient is most challenging. Management of the primary illness is no longer the priority and the focus of care shifts to optimize symptom control. An important aspect of this is recognition of end-of-life and it is often difficult to make a decision to stop anticancer treatment. This needs a very sensitive approach involving patients, their families and all concerned parties in the care of patients.

In patients with advanced cancer the following signs and symptom suggest that the patient is dying: