Chapter 28 Palatal implants for primary snoring: short- and long-term results of a new minimally invasive surgical technique

1 INTRODUCTION

Snoring is a widespread symptom affecting about 50% of the adult population. Primary snoring without sleep disordered breathing is not harmful in itself. However, as snoring often causes social embarrassment and marital disharmony, affected patients apply to their physicians for treatment.

Therefore, both patients and physicians prefer a minimally invasive and less painful procedure as a primary option for the treatment of snoring. Since its invention in 1998 interstitial radiofrequency treatment of the soft palate has gained increasing interest among the public because it was the first minimally invasive surgical treatment bearing a low morbidity as well as a remarkable success rate.1 However, it is not a single-step procedure and treating the palate excessively may still impair the various functions of the soft palate in very few cases. Furthermore, a considerable relapse of snoring 1 to 1½ {} years after the last radiofrequency treatment has to be considered.2 Due to this relapse of snoring, alternative therapies with minimal morbidity and long-term efficacy are desired. Therefore, a new procedure was developed in 2001 where woven cylindrical implants are placed within the soft palate in order to stiffen the soft palate and thus reduce snoring. These implants are made of polyethylene terephtalate, a material which has been used in heart valve surgery for the last decades.

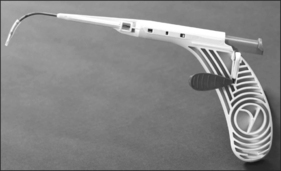

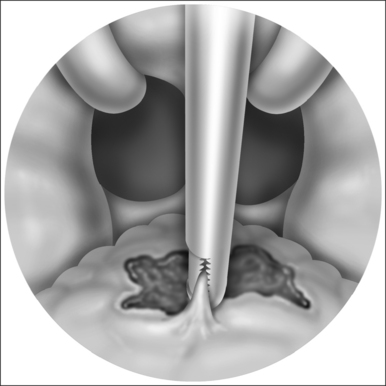

In this chapter, the patient selection criteria for the insertion of palatal implants in the treatment of snoring and its success rate as well as its morbidity are described according to the literature and to our own experience. The procedure is described in detail. It is performed identically in snorers as well as sleep apnea patients. During the last few years the delivery tool has been modified three times. It became smaller and contains more safety precautions against unwanted or incorrect implant deployment (Fig. 28.1).

2 PATIENT SELECTION

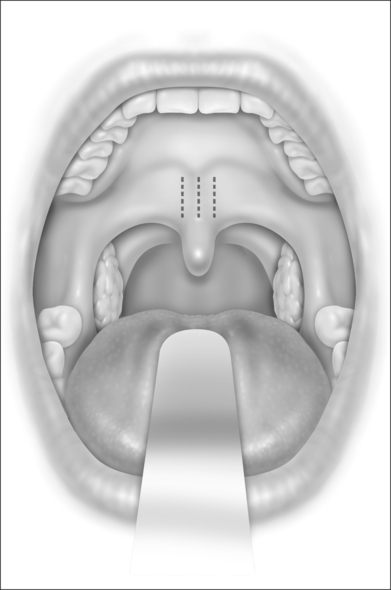

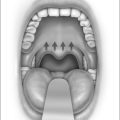

The Pillar® procedure consists of inserting implants into the junction of hard and soft palate in order to extend the hard palate, thus reducing the vibrating parts of the palate. The nature of the procedure where there is no resection or ablation of palatal tissue makes the patient selection criteria for this operation comprehensible. Patients with the following findings at the upper pharyngeal level should not receive palatal implants as a solitary intervention: nasal obstruction for whatever reason, distance between both tonsils less than 2 cm, excessive palatal and pharyngeal mucosa, and an uvula longer than 1 cm (Fig. 28.2). Patients with signs of tongue base snoring or obstruction in the clinical examination such as Friedman Tongue Position 3 or 4 (Fig. 28.3), tongue base hypertrophy, retrognathia, and floppy epiglottis are also not suitable candidates for this procedure. Obesity with a BMI above 32 kg/m² is known to impair any surgical intervention at the upper pharyngeal level and therefore is considered to be an exclusion criterion. In brief, patients without any obvious morphological anomaly in their nose and pharynx except a sufficiently long soft palate are suitable candidates for a solitary Pillar® procedure (Fig. 28.4). It has to be kept in mind that in all publications concerning the efficacy of palatal implants themselves, only those patients who fulfilled the above-mentioned inclusion criteria were treated.

The impact of nasal obstruction on snoring can be easily detected by applying a nasal decongestant and/or a nasal dilator before bedtime for a period of 7 days. If the improvement of nasal breathing during the night does not lead to a decrease of snoring, a combined versus a stepwise operation of the nose and the Pillar® procedure may be discussed with the patient. Of course, an adjunct conservative treatment with a mandibular advancement device, positional therapy, and/or weight reduction is possible at any time and vice versa. It is well documented in sleep apnea patients that palatal implants can be inserted synchronously to or as a second step after other soft palate procedures like UPPP.3 It is also possible in the case of a recurrence of symptoms after such operations.4 Future studies have to show whether this is also true for primary snorers. Radiofrequency of the soft palate, injection snoreplasty, and cautery-assisted palatal stiffening operations are not recommended as additional surgeries by us, because the tissue necrosis they induce is likely to increase the risk of implant extrusion and infection (see Complications below). There are no data concerning the combination with tongue base procedures (i.e. radiofrequency, laser resection of the lingual tonsil, genioglossus advancement, hyoid suspension), but obviously there is no surgical contraindication as different anatomical sites are addressed. However, tongue base procedures are rarely used in primary snoring anyway.

If palatal implants are used as additional surgery, one will lose the minimally invasive character of the intervention in most cases. Therefore, it has to be investigated whether the indication for an isolated Pillar® procedure may generally be extended to patients considered less suitable up to now, in order to offer this minimally invasive procedure as a real alternative to more aggressive operations as mentioned above. Furthermore, it is not yet clear whether additional methods for the assessment of the site of snoring sound generation can improve the selection process towards a better outcome. Regarding this issue, sound analysis using the SNAP®system did not increase the success rate.5 Multi-channel pressure recordings during natural sleep and videoendoscopy during wakefulness as well as under sedation are still under investigation.

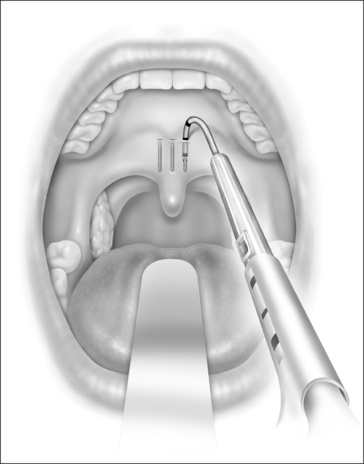

The implant is a braided segment of polyester filaments intended for permanent implantation. The implant is 18mm in length and has an outer diameter of 1.5mm. The delivery tool (See Fig. 28.1) consists of a handle and 14-gauge needle, with the implant preloaded. The implant is deployed by pushing the thumb switch. Three implants are placed near the midline into the soft palate near the junction of hard and soft palate as if the hard palate was extended by the implants. The curved needle has three markings: a full insertion marking, a halfway depth marking, and a needle tip marking. Care must be taken to remove the transport lock and the plastic sleeve covering the tip of the needle, before attempting insertion of the implants. Each delivery tool contains one implant. The delivery tools are not reusable, and should be appropriately disposed of in a sharps container after the procedure.

The exact location of the insertion sites is determined by palpating the junction of the soft and hard palate and may be marked by the surgeon. The needle is inserted in the midline first while the neck is slightly extended, thus giving more space between chest and delivery tool and making it easier to follow the angle and curvature of the soft palate. The needle is then advanced towards the free margin of the soft palate to the full insertion marking which still has to remain visible. Care must be taken to always stay in the muscle layer (Fig. 28.5). Correct positioning of the needle can be checked either by palpation or, more easily, by making the soft palate move anteriorly and posteriorly with the needle.At this point the device is unlocked by pressing the lock located beneath the slider downwards. The slider is pushed halfway, until a click is heard. The needle is then withdrawn until the halfway depth marker, and the slider is pushed all the way in, thus deploying the implant into the channel which has been created in the soft palate by the needle. The position of the slider can be determined by looking at the windows on the side of the delivery tool. The needle is then withdrawn following the curvature of the needle, by moving the delivery tool in an arching fashion. If resistance is felt while delivering the implant, it usually means that the implant is pushing against the end of the previously created tunnel. Withdrawing the needle as the slider is pushed all the way in will usually result in adequate placement of the implant. The two lateral implants are inserted in the same fashion, as close as possible to the midline implant, about 2 mm apart (Fig. 28.6). A good way of estimating this distance is by using the diameter of the needle (approx. 2 mm).

4 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT AND COMPLICATIONS

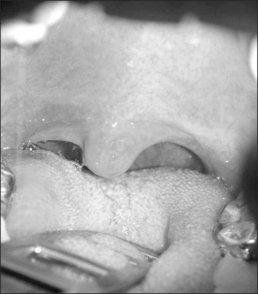

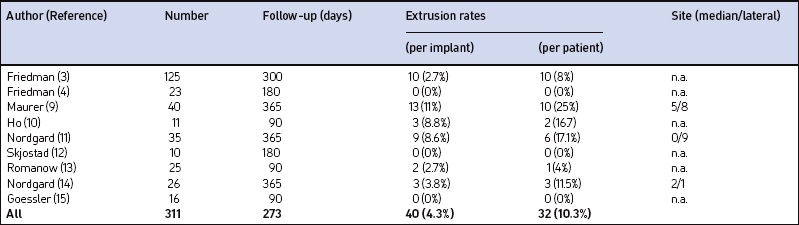

Our own data and the literature demonstrate that palatal implants can be easily implanted under local anesthesia. Sedation is usually not necessary. If – due to a sudden gagging of the patient – an implant is pushed through the mucosa at either side of the soft palate, it can be pulled out easily at once with tweezers or a forceps. A new implant can be implanted at minimal distance of the extracted implant during the same operation. Apart from that there are no relevant perioperative complications. The mean postoperative pain levels and use of analgesics are comparable to the data obtained after radiofrequency treatment (RF) of the soft palate and considerably lower than after UPPP or LAUP.6 There were no mucosal ulcerations, palatal sloughing, or fistulas detected which have been described after RF procedures7 and injection snoreplasty.8 Swallowing and speech were not subjectively affected. On the other hand, partial extrusions of one or more implants were noted during the first postoperative year in 25% of our first group of 40 snorers.9 In one patient all three implants extruded. The implants never extruded completely, making an aspiration impossible. However, we saw an ongoing extrusion of up to one-third of an implant over 2 weeks in one patient. Patients experience this partial implant extrusion either like a mild sore throat due to the concomitant or responsible infection, a foreign body, or they do not feel anything particular but discover a white spot at the oral surface of the soft palate accidentally (Fig. 28.7). If the implant is extruded through the posterior palatal surface, patients always feel a foreign body sensation or a sore throat. Therefore, a fibroscopic control of the nasopharynx is always necessary if any suspicion about implant extrusion arises. Ho et al.10 reported about 8.8% partial extrusions in 16.7% of the patients after 3 months; Nordgard11 and co-workers mentioned only two partial extrusions in 35 patients (2% of the implants) and one additional removal due to foreign body sensation during the first 90 days after the procedure. Our partial extrusion rate after 3 months is comparable. However, almost half of the partial extrusions occurred later than 90 days after implantation. There were more extrusions in the first half of the study population. Using more rigid implants increased the number of partial extrusions (five partial extrusions in 10 patients) whereas efficacy decreased compared to regular implants.12 In our own last 20 patients we did not see any extrusions during the first year after the implantation. The data available are summarized in Table 28.1. All this indicates that there is a certain learning curve. In the beginning the surgeon may tend to place the implants too superficially in order to avoid penetrating the soft palate to the nasopharynx. Second, it is rather difficult to penetrate the mucosa near the junction of the hard and soft palate as recommended. In the beginning the surgeon may thus place the implants too close to the edge of the soft palate, where it becomes rather thin. Both factors increase the risk of partial implant extrusion.

The removal of partially extruded implants is always simple if extruded to the oral surface. In some cases it can even be done without any local anesthesia. Implants extruding to the nasopharynx may eventually require general anesthesia to be removed. If desired by the patient and if there are no signs of infection (Fig. 28.8) the surgeon may substitute the removed implants during the same session. It is also possible to remove non-irritating implants if desired by the patient for any reason. However, this may be more difficult and destructive and may require general anesthesia as the implants are intact (Fig. 28.9) and thoroughly anchored in scar tissue. Therefore, we suggest not removing ineffective implants which do not cause any problems.

5 SUCCESS RATE OF THE PROCEDURE

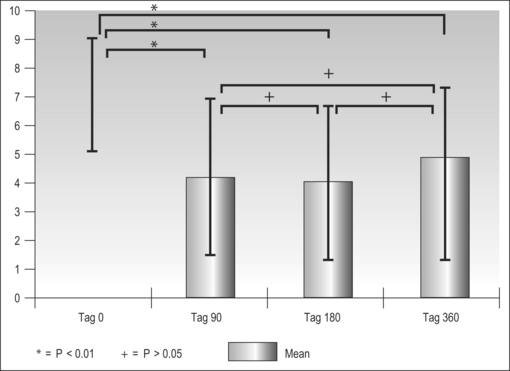

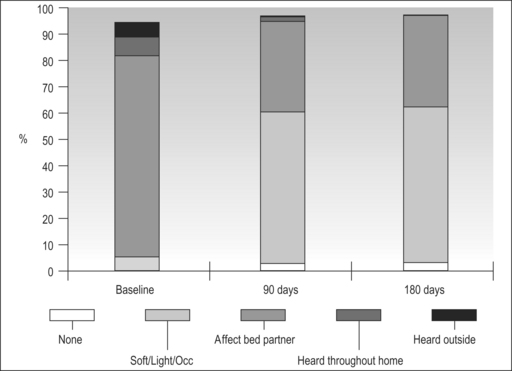

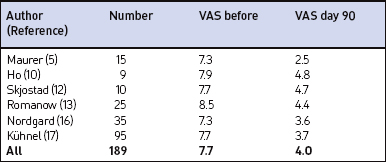

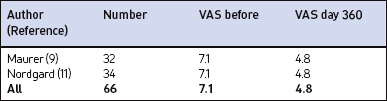

In the majority of primary snorers the soft palate is the main source of sound generation. Therefore, the first studies using palatal implants were performed on primary snorers. All patients had palatal implants as a solitary intervention and fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above. All patients received three implants. Snoring was mainly assessed using visual analogue scales which were filled in by the bedpartner. In some studies, the SNAP® recording system was additionally used in order to obtain some objective data. However, there was no relationship between subjective and objective outcome.5,9,11,16 On average, snoring could be reduced significantly from 7.7 to 4.0 on the VAS after 3 months and from 7.1 to 4.8 after 1 year (Fig. 28.10). The available data concerning 3-month and 1-year results are summarized in Tables 28.2 and 28.3. These raw results are similar to radiofrequency treatment of the soft palate. In the light of the limited data available the recurrence of snoring after an initial success seems lower with Pillar® compared to radiofrequency treatment of the soft palate. Long-term data over several years are being collected currently. More than 90% of patients and bedpartners would recommend the procedure to others, although only a few bedpartners reported a complete elimination of snoring (Fig. 28.11). Mostly snoring decreased but could still be heard. A reason for the surprisingly good patient acceptance might be the low morbidity of the procedure combined with a recognizable reduction of snoring sound intensity. However, placebo-controlled randomized trials as published for RF of the palate18 are necessary to assess the impact of Pillar® implants on simple snoring.

Table 28.2 Impact of palatal implants on snoring intensity in primary snorers, measured by visual analogue scale (VAS, 0–10 cm) after 3 months

Table 28.3 Impact of palatal implants on snoring intensity in primary snorers, measured by visual analogue scale (VAS, 0–10 cm) after 1 year

1. Powell NB, Riley RW, Troell RJ, et al. Radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the palate in subjects with sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 1998;113:1163-1174.

2. Li KK, Powell NB, Riley RW, et al. Radiofrequency volumetric reduction of the palate: an extended follow-up study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:410-414.

3. Friedman M, Vidyasagar R, Bliznikas D, Joseph NJ. Patient selection and efficacy of Pillar implant technique for the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:187-196.

4. Friedman M, Schalch P, Joseph NJ. Palatal stiffening after failed uvulopalatopharyngoplasty with the Pillar Implant System. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1956-1961.

5. Maurer JT, Verse T, Stuck BA, Hormann K, Hein G. Palatal implants for primary snoring: short-term results of a new minimally invasive surgical technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:125-131.

6. Troell RJ, Powell NB, Riley RW, et al. Comparison of postoperative pain between laser–assisted uvulopalatoplasty, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, and radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction of the palate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:402-409.

7. Stuck BA, Starzak K, Verse T, et al. Complications of temperature-controlled radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction for sleep-disordered breathing. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:532-535.

8. Brietzke SE, Mair EA. Injection snoreplasty: extended follow-up and new objective data. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:605-615.

9. Maurer JT, Hein G, Verse T, et al. Long-term results of palatal implants for primary snoring. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:573-578.

10. Ho WK, Wei WI, Chung KF. Managing disturbing snoring with palatal implants: a pilot study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:753-758.

11. Nordgard S, Stene BK, Skjostad KW, et al. Palatal implants for the treatment of snoring: long-term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:558-564.

12. Skjostad KW, Stene BK, Norgard S. Consequences of increased rigidity in palatal implants for snoring: a randomized controlled study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:63-66.

13. Romanow JH, Catalano PJ. Initial U.S. pilot study: palatal implants for the treatment of snoring. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:551-557.

14. Nordgard S, Hein G, Stene BK, et al. One-year results: palatal implants for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:818-822.

15. Goessler UR, Hein G, Verse T, et al. Soft palate implants as a minimally invasive treatment for mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:527-531.

16. Nordgard S, Wormdal K, Bugten V, et al. Palatal implants: a new method for the treatment of snoring. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124:970-975.

17. Kuhnel TS, Hein G, Hohenhorst W, Maurer JT. Soft palate implants: a new option for treating habitual snoring. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:277-280.

18. Stuck BA, Sauter A, Hormann K, et al. Radiofrequency surgery of the soft palate in the treatment of snoring. A placebo-controlled trial. Sleep. 2005;28:847-850.