Chapter 13 Pain management in the emergency department

Emergency physicians should be competent in the management of pain. The early relief of pain is a right and an expectation when a patient presents to the emergency department. The management of pain is often compromised by misunderstandings, myths, prejudice and inappropriate reliance on inflexible cookbook formulas. Good patient care demands effective pain relief; failure to effectively manage pain is a failure in the quality of care.

THE APPROACH TO PAIN MANAGEMENT

Acute pain is a symptom, not a diagnosis.

While it is important to treat the pain, the cause should always be identified and treated.

Clinical examination

ESTABLISHING A PAIN MANAGEMENT PROCESS IN THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

In order to ensure rapid and adequate analgesia for patients presenting with pain, a process of pain assessment and management needs to be in place.

Key components of this process are:

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN

Analgesia is most effective when the patient’s medications are tailored to their requirements.

Adequate pain assessment begins with the history and physical examination.

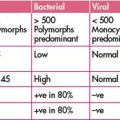

A visual analogue scale (VAS) in centimetres may be used to evaluate the patient’s subjective sensation of pain (Figure 13.1).

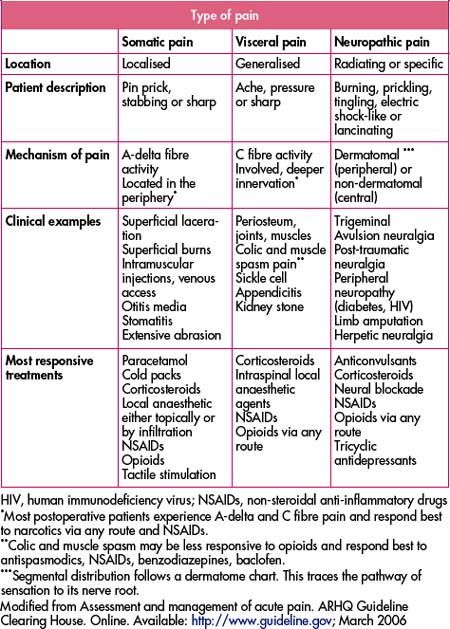

Alternatively, a numerical rating scale (NRS) from 0 to 10 (0 = no pain, 10 = worst possible pain, see Table 13.1) has been demonstrated to correlate closely with the VAS in measuring pain, with the VAS and the NRS having almost identical minimum clinically significant differences.

Table 13.1 Suggested analgesia for acute pain in adults based on the VAS or NRS

| Pain score | Suggested analgesic |

|---|---|

| 1–2 | Paracetamol PO ii tabs |

| 3–4 | Paracetamol and codeine 8 mg PO ii tabs |

| 5–7 |

THE RATIONAL USE OF ANALGESICS AND SEDATIVES

Always refer to the drug’s product information (PI) before prescribing or administration.

Guiding principles

Pharmacological agents

Simple analgesics

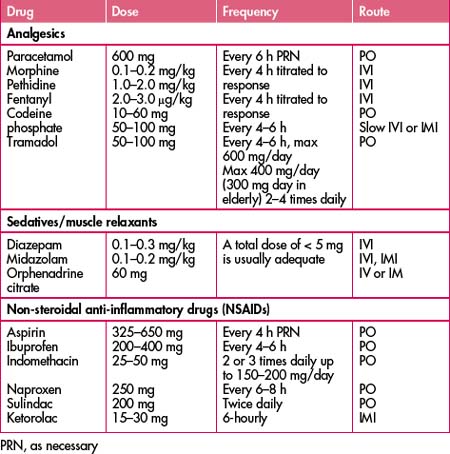

Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) with or without codeine, and paracetamol with or without codeine, are commonly used for mild pain. Both are also used as antipyretics; aspirin also has an anti-inflammatory action. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are also commonly used as analgesics. NSAIDs are more potent analgesics than paracetamol and aspirin. Table 13.3 lists the commonly used agents and their properties.

Narcotics and opioid analgesics

Natural and synthetic opioids are the most commonly use analgesic agents in the emergency department. Opiates should be administered IV and titrated to desired effect. Onset of action is rapid. They may also be administered IM or subcutaneously (SC). Respiratory depression, nausea and vomiting are the most common side effects. Concurrent administration of an anti-emetic (such as metoclopramide) should be considered, except in children under 10 years of age because of the high incidence of extrapyramidal reactions. Supplemental oxygen and oximetry monitoring should be used in patients with cardiac and lung disease. Cardiac monitoring may also be necessary.

Morphine should be used in preference to pethidine because:

In fact, there is very little evidence supporting the continued use of pethidine.

Nitrous oxide (N2O)

Contraindications include the presence of gas-containing cavities, especially a pneumothorax.

Sedating agents

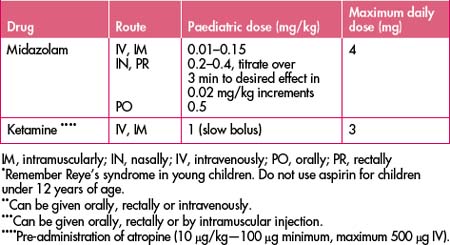

Midazolam has ideal properties for use during procedures requiring short-term sedation because of its short half-life. The dose of midazolam is 0.01–0.15 mg/kg (titrated cautiously to response). Flumazenil, a benzodiazepine antagonist, can be used to reverse the sedative effects of benzodiazepines. It is particularly useful after procedures where midazolam has been used, in order to speed up recovery. The dose is 0.2 mg followed by 0.1 mg increments up to a total of 1 mg: the usual dose is 0.3–0.6 mg. Care should be taken not to produce an acute benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Seizures may occur as a result of its use.

Ketamine

Ketamine is a dissociative anaesthetic. It induces a state of analgesia, amnesia and unresponsiveness to noxious stimuli while at the same time preserving airway and breathing reflexes. With care, it is a safe alternative to general anaesthesia for minor procedures on children in the emergency department. Ketamine should only be administered by staff with advanced airway and resuscitation skills. Patients should be fasting for at least 3 hours and fully monitored during the procedure. For doses and effects, see Table 2.1.

LOCAL ANAESTHESIA

Topical application

Topical analgesia using a local anaesthetic agent such as amethacaine (often in combination with a cycloplegic such as homatropine) is commonly used to relieve ophthalmic pain.

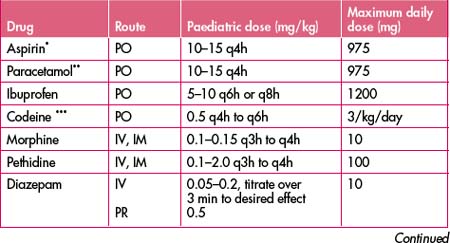

PAEDIATRIC ANALGESIA AND SEDATION

The assessment of the degree of pain in children can be difficult.

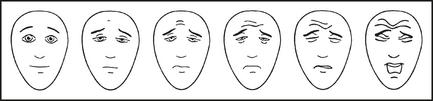

Children as young as 5 years have been shown to be capable of using the visual analogue scale (VAS). Recently the usefulness of a coloured analogue scale (CAS) and a facial affective scale (FAS, see Figure 13.2) were assessed. Both scales have numerical values on the reverse side to assist in documenting the pain severity. Almost all children are easily able to use both the CAS and VAS. A visual analogue scale, facial affective scale or a colour analogue scale should be used in assessing and monitoring pain in children.

Figure 13.2 Facial affective scale to assist children in indicating the severity of their pain

Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA et al. Faces Pain Scale—Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain 2001; 93(2):173–183. Used with permission from IASP®. See http://www.painsourcebook.ca for instructions on use of the scale.

Approach to the child

Non-pharmacological techniques including distraction, reassurance, elevation, application of ice and splinting are just as important, if not more so, in children as in adults. Children lend themselves to alternative routes of analgesic/sedative drug administration: oral, nasal, topical and rectal. The easiest manner of drug administration in children is transmucosally (either orally, nasally or rectally). While the effect of a drug administered this way is less predictable, and higher doses are required compared with parenteral administration, it is a very effective and useful way of administering drugs to apprehensive children (Table 13.4).

ANALGESIA IN THE ELDERLY

Pain relief is a common and important factor in the quality of life of the elderly.

Where possible, because of the associated adverse events, NSAIDs should be avoided in the elderly.

ANALGESIA IN SPECIAL SITUATIONS

There are a number of common clinical situations in the emergency department where a combination of agents or a different approach is required to achieve the desired analgesic and sedative effect (Table 13.5).

Table 13.5 Emergency department approach to analgesia in special situations

| Indication | Analgesic(s) of choice | Adjuncts |

|---|---|---|

| Cardioversion |

IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously; PO, orally; PR, rectally

PATIENT MONITORING

Monitoring of the patient’s vital signs (temperature, pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, level of consciousness, oximetry, pain score) should begin before and continue throughout the recovery phase. The intensity of monitoring will depend on the level of sedation/analgesia, preexisting illness (cardiac or respiratory disease) and the patient’s general condition.

Capnography should also be used where there is a risk of hypercapnia.

PATIENT DISCHARGE

Full recovery from the side effects of analgesia should take place prior to discharge (Box 13.1). Patients, or their parents in the case of children, should be given both verbal and written instructions (Box 13.2).

Box 13.1 Discharge criteria after sedation and analgesia

Return to baseline verbal skills∗

Return to baseline muscular control function∗

Return of sensation and muscle function where a nerve block has been used

Return to baseline mental status

∗ These items may need to be modified to account for the patient’s visit to the emergency department

Box 13.2 Paediatric discharge instructions

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

SUMMARY

Non-pharmacological strategies should also be utilised where appropriate.

Special attention needs to be given to unresponsive or unusual pain and to the very young and elderly.

DEFINITIONS

Analgesia—absence of pain; commonly used to mean adequate pain relief.

Drug tolerance—this occurs when a fixed dose of a drug produces a decreasing effect so that a dose increase is required to maintain a stable effect; the effect occurs particularly with opioids.

American College of Emergency Physicians. Pain management in the emergency department. Online. Available: www.acep.org/practres.aspx?id+29596; 12 June 2008.

American Society of Anesthesiologists website. Available: http://www.asahq.org; 23 June 2008.

Australia and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) website. Available: http://www.anzca.edu.au; 12 June 2008.

Australian College for Emergency Medicine. Guidelines for implementation of the Australian triage scale in emergency departments. Online. Available: http://www.acem.org.au/oren/documents/triageguide.htm.

Australian Medicines Handbook 2008. Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd, Adelaide, 2008.

Beggs S. Paediatric analgesia. Australian Prescriber. 2008;31:63-65.

Bijur P.E., Sliver W., Gallegher E.J. Reliability of the visual analog scale for measurement of acute pain. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:1153-1157.

Bruckenthal P. Assessment of pain in the elderly patient. Clin Geriatr Med. 2008;24:213-236.

Forero R., Mohsin M., McCarthy S. Prevelance of morphine use and time to initial analgesia in an Australian emergency department. Emerg Med Australia. 2008;20:136-143.

Fry M., Holdgate A. Nurse-initiated intravenous morphine in the emergency department: efficacy, rate of adverse events and impact on time to analgesia. Emerg Med. 2002;14:249-254.

International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) website. Available: http://www.iasp-pain.org; 12 June 2008.

Kelly A.M. Setting the benchmark for research in the management of acute pain in emergency department. Emerg Med. 2001;13:57-60.

Little M. First aid for jellyfish stings: do we really know what we are doing? Emerg Med Australia. 2008;20:78-80.

McCleane G. Pain perception in elderly patients. Clin Geriatr Med. 2008;24:203-211.

National Guidelines Clearing House website. Available: http://www.guidelines.gov; 12 June 2008.

National Health and Medical Research Council website. Available: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications; 12 June 2008.

New South Wales Department of Health CIAP website. Available: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au.

Pediatric Emergency Medicine Reports. Pediatric procedural sedation. Part 1, Personnel, monitoring, and patient assessment. Part 2, Selecting an agent. 2007;12:5-6.

Priestly S.J., Taylor J., McAdam C.M., et al. Ketamine sedation for children in the emergency department. Emerg Med. 2001;13:82-90.

Smith H.S. Overview of pain management in older persons. Clin Geriatr Med. 2008;24:185-201.

The Children’s Hospital at Westmead Handbook. McGraw-Hill, Sydney, 2004.

Victorian Medical Postgraduate Foundation. Analgesic guidelines. Melbourne: Victorian Medical Postgraduate Foundation; 1995.

Wang N.E., Vlahos J. Pediatric procedural sedation: personnel, monitiring, and patient assessment. Part 1, Pediatric emergency medicine reports. Part 2, Selecting an Agent. 2007;12:5-6.