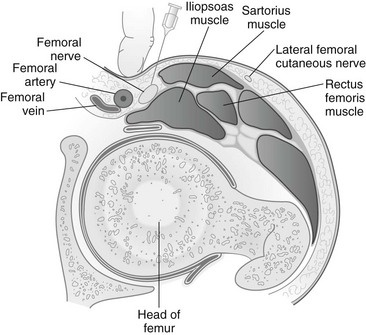

Pain Management

Effective pain management can dramatically enhance a rescue effort and minimize morbidity and mortality. Any health care worker providing medical support to a backcountry trip or expedition should be adequately prepared to provide pain relief (Box 24-1). This may be the only therapeutic modality available for the patient.

Evaluation of Pain

The basis of the wilderness pain evaluation should include the following:

Physical Methods for Treatment of Pain

1. An injured extremity is wrapped distal to proximal, with a cloth wrap, rubber Esmarch bandage, or an elasticized (Ace) wrap.

2. Resultant mild anesthesia may occur because of compression of peripheral nerves.

3. If pain increases, discontinue this method.

4. Compression anesthesia may be safe and appropriate in a wilderness setting if other methods or pharmacologic agents are unavailable or contraindicated.

Cryoanalgesia

1. Wilderness cryoanalgesia may be applied with ice, snow, or frigid water.

2. Cryoanalgesia requires a 20- to 30-minute minimum duration for adequate therapeutic effect.

3. Prevention of iatrogenic frostbite and generalized hypothermia while using cold therapy is critical. How long a tissue will tolerate a cold compress before experiencing cellular damage depends on preexisting tissue hypothermia, peripheral versus central nature of the tissue, and temperature and pressure of the cold compress.

4. Cold water immersion may exacerbate injury in persons with snakebite because of venom-compromised tissues.

5. Cold packs are rarely beneficial for marine coelenterate (e.g., jellyfish) envenomations, which may benefit from application of heat (see Chapter 53).

6. Commercial cold packs typically contain a gel of water and propylene glycol, or other similar antifreeze and heat exchange substances, which may be further cooled in cold water or snow to prolong their effectiveness.

7. A reasonable practice is to place a dry, thin cotton cloth or piece of foam between the skin and cold metal cylinders, ice, snow, or cold packs. Remove cold therapy every 15 minutes to assess tissue status.

Heat Therapy

1. Heat application is not usually recommended for initial (up to 48 hours after the injury) pain management of acute trauma because it may lead to increased edema and bleeding.

2. Heat can be used for pain management in the wilderness, especially for patients with chronic pain conditions.

3. Heat applied to the skin of the abdomen may markedly reduce gastrointestinal peristalsis and uterine contractions and thus decrease pain associated with these organs.

4. Application of heat need not be extreme. Temperatures of 37.8° C to 40° C (100° F to 104° F) for 10 to 20 minutes generally provide comfort without creating thermal injury.

5. Heat therapy should be avoided in cognitively impaired persons and for tissue that is anesthetic or ischemic, to prevent further unintended tissue injury.

6. Heat therapy may improve certain marine envenomations. It is generally helpful for spine (e.g., sea urchin, starfish, scorpionfish, stingray) punctures and perhaps also helpful for certain jellyfish stings (see Chapter 53).

7. Liniments and balms are not true heat-transfer agents but consist of multiple botanical or chemical substances that make the tissue feel warm through counterirritant effects and subsequent vasodilation. These substances may help abate a traveler’s soreness and stiffness. Common ingredients include menthol, camphor, mustard oil, eucalyptus oil, methyl nicotinate, methyl salicylate, and wormwood oil. These products are generally only recommended on intact skin with a light cloth or plastic covering and should not be placed on mucous membranes. They should not be used with tight compresses or external heat sources. Topical capsaicin in low concentration is used to relieve pain from arthritis, but its application may cause a marked sensation of skin burning.

Splinting

1. Splints (see Chapter 18) should be well padded to prevent further surface trauma.

2. Splints may be accompanied by pressure dressings or cold compresses for additional pain management.

3. Regular reevaluation of tissue circulatory status is critical to prevent damage from swelling, frostbite, or ischemia in immobile, splinted limbs.

Topical Anesthetics

1. A local anesthetic may provide relief in a topical application before more invasive cleansing and debridement.

2. The local anesthetic EMLA is a mixture of 2.5% lidocaine and prilocaine. After this cream is applied to intact skin under a nonabsorbent dressing for at least 45 minutes, an invasive procedure such as intravenous (IV) needle insertion may be more easily tolerated.

3. Lidocaine gel can also be used for this purpose (Table 24-1).

Table 24-1

Comparable Anesthetic Dosages* for Peripheral Blocks and Local Infiltration

| DOSAGE (mg/kg) | |

| Amide Anesthetics | |

| Lidocaine | 5 |

| Prilocaine | 5 |

| Etidocaine | 4 |

| Mepivicaine | 5 |

| Bupivacaine | 2 |

| Ester Anesthetics | |

| Procaine | 5 |

| Tetracaine | 1-2 |

| 2-Chloroprocaine | 5 |

Local Anesthetic Pharmacology

1. Infiltration into a highly vascular site such as around an intercostal nerve leads to more rapid escalation of anesthetic blood level than does injection into less vascular subcutaneous tissues. Use of an anesthetic/epinephrine mixture leads to slower absorption but must be avoided when injecting distal extremities and digits, where epinephrine-induced vasoconstriction may lead to acute ischemic injury. Because of the possibility of unintentional direct intravascular injection, all local and regional anesthetic infiltrations should be made after negative aspiration for blood and in small aliquots between aspiration attempts.

2. As anesthetic toxicity levels are approached, common early symptoms include circumoral numbness, tinnitus, and cephalgia. Central nervous system (CNS) toxicity in the form of seizures occurs at lower anesthetic blood levels than does cardiotoxicity, seen as ventricular arrhythmias and cardiovascular collapse. Generally cardiotoxicity is achieved at approximately 150% of the blood level concentrations required for anesthetic CNS toxicity. Bupivacaine has demonstrated increased cardiotoxicity relative to lidocaine.

3. Anesthetic allergy per se is uncommon, with perhaps 99% of all adverse anesthetic reactions actually related to pharmacologic toxicity of the anesthetic or to epinephrine mixed with the agent.

Anesthetic Infiltration Techniques and Nerve Blocks

1. Soft tissue analgesia is accomplished with local injection of 1% lidocaine. Generally the maximum injectable dose for lidocaine is 4 mg/kg. In larger wounds, injections proceed from an area previously anesthetized, to lessen discomfort from subsequent injections.

2. Local anesthetic injection typically causes temporary pain resulting from the solution’s pH. Buffered solutions are available or may be created by adding sodium bicarbonate (1 mEq/mL) to lidocaine or other anesthetic in a 1 : 10 ratio, bicarbonate to anesthetic. Tolerance to the injection is improved by gentle and slow injection, allowing prudence with the total dose of anesthetic. Buffering lidocaine with sodium bicarbonate shortens the life span of the resulting solution, which should be discarded after 24 hours.

3. Epinephrine may provide useful hemostasis, especially in head and scalp lacerations. Although recent literature supports the safe use of epinephrine added to local anesthetic injected in the distal extremities, continue to exercise caution with epinephrine in the nose, ears, and digits to avoid possible ischemic injury and subsequent necrosis.

4. Many central and regional nerve blocks require special training, including a thorough knowledge of anatomy and management of potential complications, but several blocks can be appropriate in a wilderness setting if the physician is cautious and limits the amount of anesthetic injected. Make all infiltrations after aseptic preparation of the skin, whenever possible.

Digital Nerve Blocks

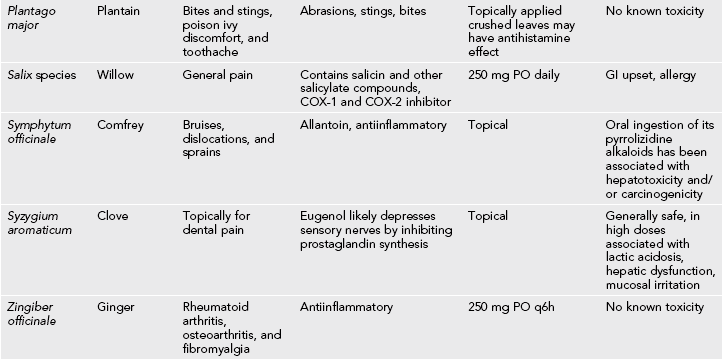

Anesthesia to the digits is easily accomplished with a low-volume field block to the medial and lateral aspects of the digit at the base of the respective phalanx (Fig. 24-1).

FIGURE 24-1 Digital nerve block. (Courtesy Bryan L. Frank.)

1. Approach the digital nerves from the dorsum of the hand or foot rather than from the palm or sole.

2. The dorsal digital nerves and proper digital nerves course along the medial and lateral aspects of the digits, approximately at the 10- and 2-o’clock and 4- and 8-o’clock positions, respectively.

3. A satisfactory digital nerve block is created by injecting 3 to 5 mL of lidocaine 0.5% to 1% with a 25-gauge or smaller-diameter needle to the medial and lateral aspects of the proximal digit.

Wrist Blocks

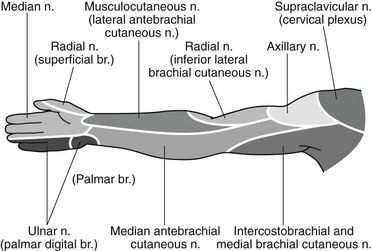

The entire hand may be anesthetized by blocking the nerves at the wrist. The radial nerve supplies the cutaneous branches of the dorsum of the hand and thumb and distally to the distal interphalangeal joints of the index, long, and radial aspect of the ring fingers (Figs. 24-2 and 24-3). Median nerve sensory distribution includes the palmar surface of the hand, ulnar aspect of the thumb, palmar aspect of the index finger, and long and radial portions of the ring finger. Median nerve innervation extends dorsally over the index, long, and ring fingers to the distal interphalangeal joint. The ulnar nerve transmits sensation from the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the lateral hand, the fifth finger, and the ulnar half of the ring finger.

1. Using a 25- or 27-gauge needle, inject 2 to 4 mL of lidocaine 1% in the subcutaneous tissue overlying the radial artery. A superficial subcutaneous injection from this point and over the radial styloid anesthetizes cutaneous branches from the proximal forearm and extending into the hand.

2. Block the median nerve with 2 to 4 mL of lidocaine 1% just proximal to the palmar wrist crease between the tendons of the palmaris longus and the flexor carpi radialis muscles. Make the injection deep to the volar fascia.

3. If a paresthesia is elicited during the injection procedure (resulting from contact with the nerve), withdraw the needle slightly before completing the injection.

4. Block the ulnar nerve with 2 to 4 mL of lidocaine 1% injected just lateral to the ulnar artery, which is radial to the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon at the level of the ulnar styloid.

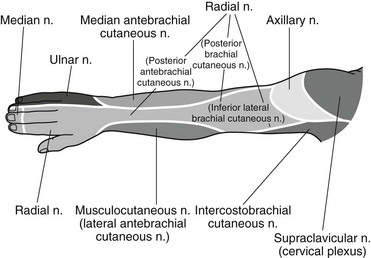

Axillary Nerve Block

Sites distal to the elbow can be blocked by placing local anesthetic near the musculocutaneous, median, radial, and ulnar nerves at the distal axilla, guided by the axillary artery pulse (Fig. 24-4).

1. Position the patient supine with shoulder abducted to 90 degrees and externally rotated, with the elbow flexed.

2. Stand or sit at the patient’s side caudal to the arm, and identify the axillary pulse over the proximal humerus.

3. The site of entry is sterilized and local anesthesia injected locally before a blunt needle is placed. Blunt needles have a shorter bevel than do traditional hypodermic needles. These needles may be safer when performing nerve blocks, because they may be less likely to injure vascular and neural structures.

4. A 22-gauge blunt needle is then advanced superior to the pulse. The musculocutaneous nerve lies deep to the artery, and this is where 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic is deposited.

5. Superficial to the musculocutaneous nerve and the pulse of the axillary artery is the median nerve, where an additional 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic is deposited.

6. The needle is withdrawn to just under the surface of the skin and then redirected inferior (medial) and deep to the artery, where the radial nerve is located; another 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic is deposited.

7. Finally, the needle is withdrawn to the depth of the axillary artery, where the ulnar nerve is located, and the remaining 5 to 10 mL of local anesthetic is deposited.

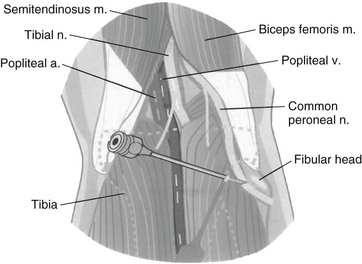

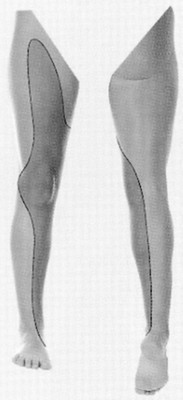

Ankle Blocks

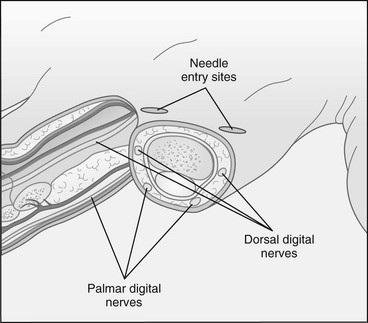

Anesthesia of the foot is easily accomplished with blocks of the sensory nerves at the ankle (Fig. 24-5).

FIGURE 24-5 Ankle block.

1. Using a 25-gauge needle, block the deep peroneal nerve, which provides sensation between the great and second toes, with 5 mL of lidocaine 1% between the tendons of the tibialis anterior and the extensor hallucis longus at the level of the medial and lateral malleoli. The needle may be passed to the bone just lateral to the dorsalis pedis artery.

2. Inject the superficial peroneal nerve with 5 mL of lidocaine 1% with a superficial ring block between the injection of the deep peroneal nerve and the medial malleolus. This blocks sensation to the medial and dorsal aspects of the foot.

3. Inject the posterior tibial nerve with 5 mL of lidocaine 1% just posterior to the medial malleolus, adjacent to the posterior tibial artery.

4. Block the sural nerve, which provides sensation to the posterolateral foot, with a similar volume of lidocaine 1%, between the lateral malleolus and Achilles tendon, followed by a subcutaneous infiltration from this site and over the lateral malleolus.

5. Paresthesias are sought in these blocks and will increase the likelihood of success. Posterior tibial nerve distribution includes the heel and plantar foot surface. Follow paresthesias by a slight withdrawal of the needle before injection.

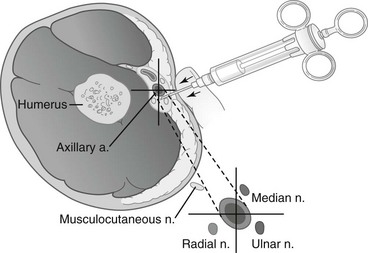

Common Peroneal Nerve Block

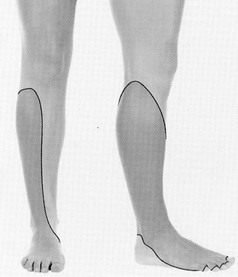

A common peroneal block may be helpful for distal tibia and ankle trauma (Figs. 24-6 and 24-7).

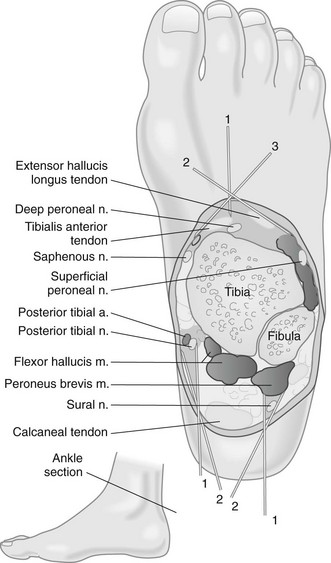

Femoral Nerve Block (Fig. 24-8)

The sensory distribution of the femoral nerve includes the anterior and medial thigh and knee as well as the medial lower leg in the saphenous nerve distribution (Fig. 24-9). A femoral nerve block can be used for a femur fracture.

FIGURE 24-8 Femoral nerve block.

1. With the patient supine, the inguinal ligament, anterior-superior iliac spine, pubic tubercle, and femoral pulse at the level of the inguinal ligament are identified.

2. A 4-inch, 22-gauge, blunt-bevel needle is entered through the skin 1 cm (0.4 inch) lateral to the femoral pulse and advanced in the anterior-posterior plane.

3. As the needle is advanced, a paresthesia may be elicited, although this is variable.

4. A total volume of 20 to 40 mL of local anesthetic is injected while redirecting the needle from the initial medial position adjacent to the femoral artery to a more lateral position, thereby achieving a field block.

5. The use of 0.25% bupivacaine will provide good analgesia; if motor block and anesthesia are necessary, 0.5% bupivacaine should be used.

6. Because this is a field block, it may be slower in onset than other nerve blocks.

7. The femoral artery is in close proximity to the injection site, so arterial puncture of the artery and intravascular injection are possible (see Fig. 24-8).

Pharmacologic Treatment of Pain

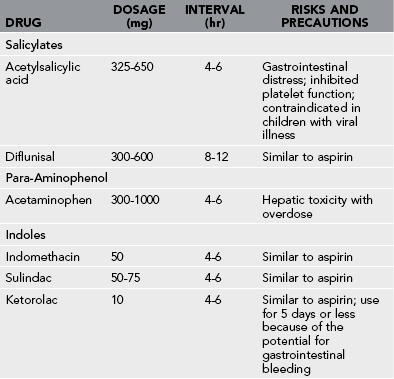

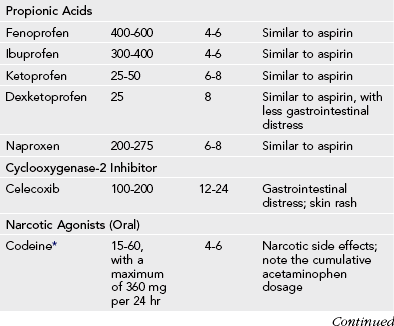

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have both analgesic and antiinflammatory properties. Common agents, such as ibuprofen and naproxen, are readily available and offer first-line treatment for various minor aches and pains (Table 24-2). They offer an inexpensive and effective means of treatment without concern about the possible adverse effects of opioids and are generally free from regulation in foreign countries. Ketorolac is a parenterally administered NSAID that can be used for moderate to severe pain (see Table 24-2). Recommended dosage is 60 mg IM or 30 mg IV q4-6h. Use half this dose if the patient is older than 65 years or weighs less than 50 kg (110.2 lb). Oral dose is 10 mg.

Table 24-2

Common Oral Analgesics: Dosage Recommendations for 70-kg (154-lb) Adults

*Codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone are manufactured as single drug preparations, and also commonly in combination with acetaminophen. Dosing provided is for the narcotic component only. total daily acetaminophen administration should not exceed 4 g daily.

From Burnham T, Short RM, editors: Drug facts and comparisons, St Louis, 1999, Facts and Comparisons Inc; and Emermann CL, Spenetta J: Pain management in the emergency department. Emerg Med Rep 23:53, 2002.

Narcotic Analgesics

1. Opiates are effective for moderate to severe pain.

2. Oral administration remains the easiest form of delivery and may be accomplished with an isolated opiate (e.g., oxycodone) (see Table 24-2) or in combination with acetaminophen (e.g., Vicodin, Norco, Lortab, Percocet)

2. Care should be taken to avoid consuming more than 4 g of acetaminophen in 24 hours, because hepatic toxicity may occur above this dosage.

3. Morphine remains a gold standard medication and is available for both oral and parenteral use.

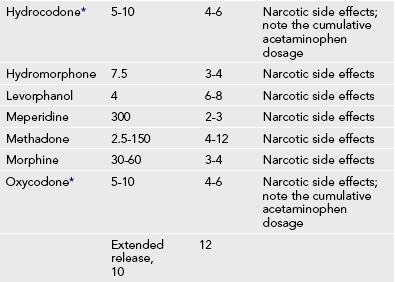

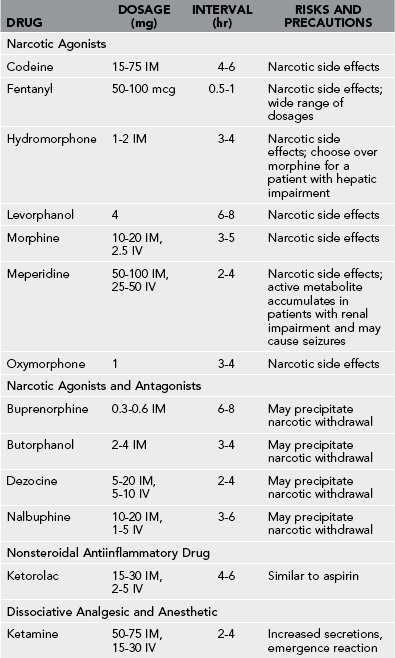

4. IV administration of opioids reduces variability introduced by oral administration and decreases the time to onset of analgesia (Table 24-3).

Table 24-3

Common Parenteral Analgesics: Dosage Recommendations for 70-kg (154-lb) Adults

IM, Intramuscularly; IV, intravenously.

From Burnham T, Short RM, editors: Drug facts and comparisons, St Louis, 1999, Facts and Comparisons Inc; and Emermann CL, Spenetta J: Pain management in the emergency department. Emerg Med Rep 23:53, 2002.

5. IV administration can be by intermittent injection or continuous infusion. Intermittent bolus injections in remote locations are more practical.

6. IM administration of opioids is feasible in remote areas, but drugs have variable absorption from different muscle groups.

7. Subcutaneous administration of opioids may have similar efficacy as IM administration and is less painful. The dosing for subcutaneous administration is the same as IM.

8. Manage nausea and vomiting with ondansetron (Zofran).

9. For oversedation and opiate side effects, use naloxone judiciously in 40-mcg increments.

10. Full-dose (0.4 mg) naloxone is still the appropriate treatment for respiratory depression.

Additional Agents

Narcotic Agonist-Antagonist Combinations

1. Drugs in this class include buprenorphine, butorphanol, and nalbuphine.

2. In the wilderness setting, a drug that may be useful is transnasal butorphanol (Stadol NS).

a. The recommended dose for initial nasal administration is 1 mg (1 spray in one nostril).

b. Adherence to this dose reduces the incidence of drowsiness and dizziness. If adequate pain relief is not achieved within 60 to 90 minutes, an additional 1 mg dose may be given.

c. Stadol is rapid acting and offers good analgesia but can cause significant sedation and often considerable dysphoria.

Ketamine

1. As little as 10 to 20 mg given IV or IM to an adult produces the desired analgesia.

2. If needed, the dose may be repeated every 2 to 3 hours. Titration to effect or to the presence of side effects is imperative.

3. Psychomimetic effects (e.g., hallucinations, bad dreams) are seen with higher doses and may limit use of this drug.

4. A calm and quiet setting with minimal stimulation is the ideal setting for use.

5. Benzodiazepines (e.g., midazolam, 2 mg IV) are effective for blunting the adverse psychomimetic response.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies

1. Sterile acupuncture needles are compact, lightweight, and easy to include in a daypack or first-aid kit. Integration of acupuncture into the care of wilderness trauma, pain, and illness may dramatically enhance patient comfort and facilitate extrication from a remote setting.

2. Most acupuncture treatment requires substantial training to be responsibly integrated with conventional Western therapies. National and international standards of training have been established for Western-trained physicians who desire to incorporate acupuncture into their traditional medical practices.

3. Physicians interested in learning acupuncture may contact the American Academy of Medical Acupuncture for information on training programs designed specifically for physicians that meet or exceed standards established by the World Health Organization.